Ralph Johnson Bunche was born in Detroit, Michigan. His father, Fred Bunche, was a barber in a shop having a clientele of whites only; his mother, Olive (Johnson) Bunche, was an amateur musician; his grandmother, «Nana» Johnson, who lived with the family, had been born into slavery …

Ralph Bunche – Speed read

Ralph Bunche was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating a cease-fire between Israelis and Arabs during the war which followed the creation of the state of Israel in 1948.

Full name: Ralph Johnson Bunche

Born: 7 August 1904, Detroit, MI, USA

Died: 9 December 1971, New York, NY, USA

Date awarded: 22 September 1950

Peace mediator in the Middle East

On assignment from the UN, Ralph Bunche helped to develop a plan to divide Palestine between Jews and Arabs in 1947. All the Arab states in the Middle East were opposed to a Jewish state, and they attacked Israel when it was founded in 1948. The UN appointed Folke Bernadotte (Sweden) as peace mediator, with Ralph Bunche as his chief aide. Bernadotte and Bunche proposed a new partition plan intended to end the war, but the Jews vehemently opposed the plan. Bernadotte was subsequently assassinated by an extremist faction, and Bunche was asked to take over as chief mediator. Although he was unable to successfully negotiate a peace accord, Bunche achieved a ceasefire between Israel and the Arab states in 1949. By that time the Israelis had conquered more territory than was to have be their share according to the original UN plan.

“Ralph Bunche (…) You have a long day´s work ahead of you. May you succeed in bringing victory to the ideals of peace, the foundation upon which we must build the future of mankind.”

Gunnar Jahn, Chairman of the Nobel Committee, Presentation Speech 11 December, 1950.

Bunche and the partitioning of Palestine

The Palestinian problem is “the sort of problem for which no really satisfactory solution is possible,” wrote a frustrated Ralph Bunche in 1947. He was sent to Palestine by the UN’s first secretary-general, Trygve Lie (Norway), to assist with the partitioning of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. The Arabs were completely opposed to the partition plan, while many Jews wanted all of Palestine to be made theirs. The plan presented to the UN called for the establishment of two states, with a UN-governed Jerusalem. This would guarantee Jews, Christians and Muslims, alike, access to the city’s holy sites.

Ralph Bunche and Folke Bernadotte

UN envoys Folke Bernadotte and Ralph Bunche tried to end the war between the Israelis and Arabs in 1948. They proposed a new partition plan for Palestine that they hoped both parties would accept. An extremist Jewish faction objected to it so strongly, however, that it decided to assassinate both Bernadotte and Bunche. Bunche escaped death because he was delayed en route, missing the car scheduled to convey him and Bernadotte to a meeting. When the car stopped at a roadblock a young Jewish man fired his sub-machine gun into it, killing Folke Bernadotte.

“To the common man, the state of world affairs is baffling. All nations and peoples claim to be for peace. But never has peace been more continuously in jeopardy.”

Ralph Bunche, Nobel Prize lecture, 11 December, 1950.

Learn more

Article

Born in Detroit, Michigan, Bunche lost his parents at a young age. He was instead brought up by his grandmother in Los Angeles. She, who had been born into slavery, proved to be a great influence in his life, championing tolerance, discouraging bitterness and instilling in him the message that everyone has the right to be treated equally.

Ralph Bunche’s enduring fame arose from his service to the US government and, from 1946, the UN. His peace negotiations in this later role led to him receiving the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize.

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Ralph Bunche – Facts

Ralph Bunche – Acceptance Speech

Ralph Bunche’s Acceptance Speech, on the occasion of the award of the Nobel Peace Prize, Oslo, December 10, 1950

Your Majesty,

Your Royal Highnesses,

Mr. President of the Nobel Committee,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

To be honored by one’s fellow men is a rich and pleasant experience. But to receive the uniquely high honor here bestowed today, because of the world view of Alfred Nobel long ago, is an overwhelming experience. To the President and members of the Nobel Committee I may say of their action, which at this hour finds its culmination, only that I am appreciative beyond the puny power of words to convey. I am inspired by your confidence.

I am not unaware, of course, of the special and broad significance of this award – far transcending its importance or significance to me as an individual – in an imperfect and restive World in which inequalities among peoples, racial and religious bigotries, prejudices and taboos are endemic and stubbornly persistent. From this northern land has come a vibrant note of hope and inspiration for vast millions of people whose bitter experience has impressed upon them that color and inequality are inexorably concomitant.

There are many who figuratively stand beside me today and who are also honored here. I am but one of many cogs in the United Nations, the greatest peace organization ever dedicated to the salvation of mankind’s future on earth. It is, indeed, itself an honor to be enabled to practise the arts of peace under the aegis of the United Nations.

As I now stand before you, I cannot help but reflect on the never-failing support and encouragement afforded me, during my difficult assignment in the Near East, by Trygve Lie:, and by his Executive Assistant, Andrew Cordier. Nor can I forget any of the more than 700 valiant men and women of the United Nations Palestine Mission who loyally served with Count Bernadotte and me, who were devoted servants of the cause of peace, and without whose tireless and fearless assistance our mission must surely have failed. At this moment, too, I recall, all too vividly and sorrowfully, that ten members of that mission gave their lives in the noble cause of peace-making.

But above all, there was my treasured friend and former chief, Count Folke Bernadotte, who made the supreme sacrifice to the end that Arabs and Jews should be returned to the ways of peace. Scandinavia, and the peaceloving world at large, may long revere his memory, as I shall do, as shall all of those who participated in the Palestine peace effort under his inspiring command.

In a dark and perilous hour of human history, when the future of all mankind hangs fatefully in the balance, it is of special symbolic significance that in Norway, this traditionally peace-loving nation, and among such friendly and kindly people of great good-will, this ceremony should be held for the exclusive purpose of paying high tribute to the sacred cause of peace on earth, good-will among men.

May there be freedom, equality and brotherhood among all men. May there be morality in the relations among nations. May there be, in our time, at long last, a world at peace in which we, the people, may for once begin to make full use of the great good that is in us.

Ralph Bunche – Photo gallery

1 (of 4) Ralph Bunche arriving in Stockholm, Sweden, a few days after the Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony in Oslo, Norway. Photo taken on 15 December 1950 at the Central station in Stockholm.

Photo: Yngve Karlsson. Source: Stockholms stadsmuseum. CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SE

2 (of 4) Ralph Bunche, United Nations Under-Secretary (right), greeting Martin Luther King, Jr. and his wife Coretta. Photo taken in New York, 4 December 1964.

Photo by Authenticated News/Getty Images

3 (of 4) United Nations Secretary Dag Hammarskjöld (left) and UN Representative Dr. Ralph J. Bunche (middle) arriving in Leopoldville airport, 1 July 1960.

Photo by Terence Spencer/Popperfoto via Getty Images

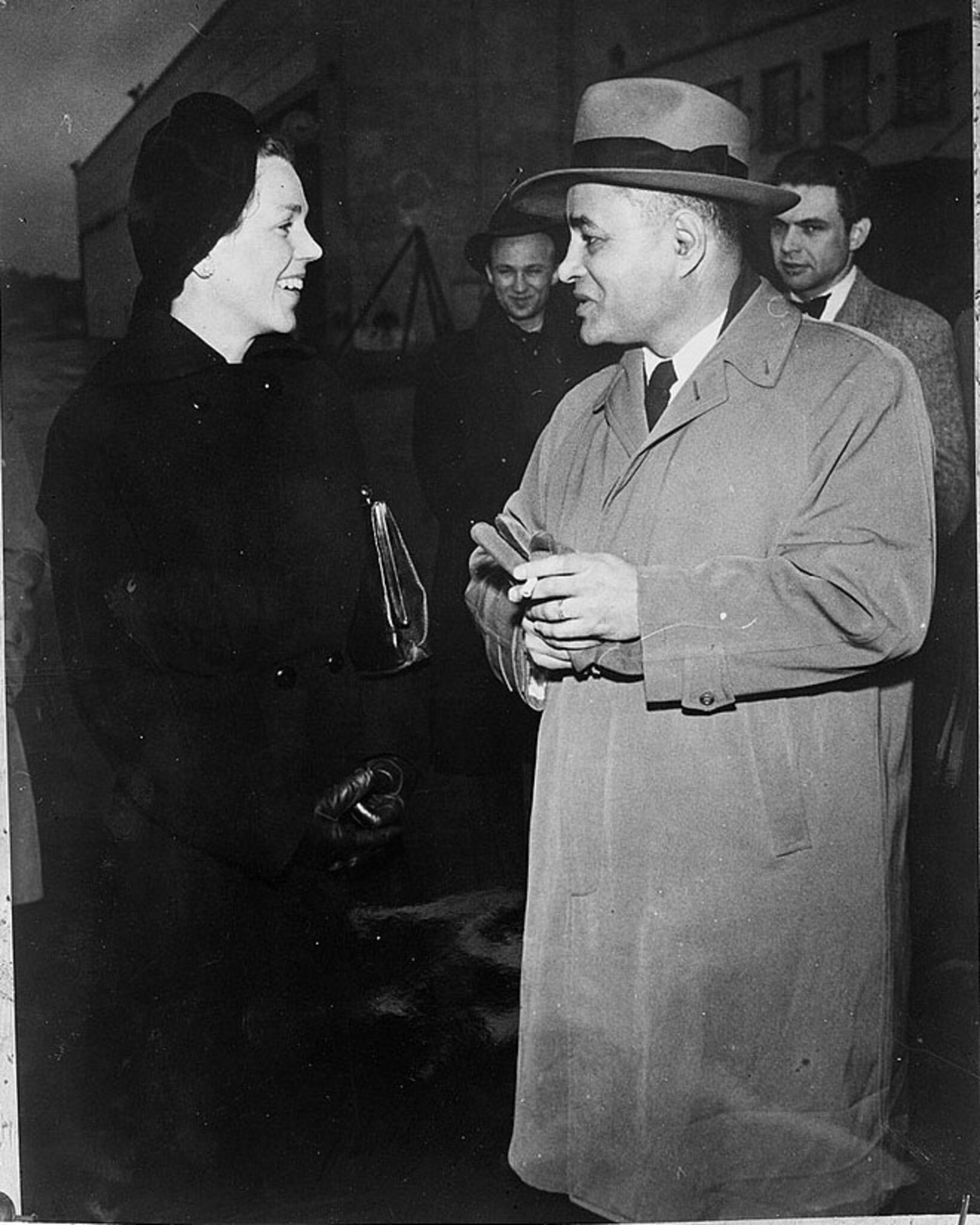

4 (of 4) Dr. Ralph Bunche in Stockholm with Estelle Manville, the widow of Count Folke Bernadotte, 10 april 1949.

Photographer unknown. Photo collection Anefo, Het Nationaal Archief, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ralph Bunche – Nominations

Ralph J. Bunche – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture*, December 11, 1950

Some Reflections on Peace in Our Time

In this most anxious period of human history, the subject of peace, above every other, commands the solemn attention of all men of reason and goodwill. Moreover, on this particular occasion, marking the fiftieth anniversary of the Nobel Foundation, it is eminently fitting to speak of peace. No subject could be closer to my own heart, since I have the honour to speak as a member of the international Secretariat of the United Nations.

In these critical times – times which test to the utmost the good sense, the forbearance, and the morality of every peace-loving people – it is not easy to speak of peace with either conviction or reassurance. True it is that statesmen the world over, exalting lofty concepts and noble ideals, pay homage to peace and freedom in a perpetual torrent of eloquent phrases. But the statesmen also speak darkly of the lurking threat of war; and the preparations for war ever intensify, while strife flares or threatens in many localities.

The words used by statesmen in our day no longer have a common meaning. Perhaps they never had. Freedom, democracy, human rights, international morality, peace itself, mean different things to different men. Words, in a constant flow of propaganda – itself an instrument of war – are employed to confuse, mislead, and debase the common man. Democracy is prostituted to dignify enslavement; freedom and equality are held good for some men but withheld from others by and in allegedly “democratic” societies; in “free” societies, so-called, individual human rights are severely denied; aggressive adventures are launched under the guise of “liberation”. Truth and morality are subverted by propaganda, on the cynical assumption that truth is whatever propaganda can induce people to believe. Truth and morality, therefore, become gravely weakened as defences against injustice and war. With what great insight did Voltaire, hating war enormously, declare: “War is the greatest of all crimes; and yet there is no aggressor who does not colour his crime with the pretext of justice.”

To the common man, the state of world affairs is baffling. All nations and peoples claim to be for peace. But never has peace been more continuously in jeopardy. There are no nations today, as in the recent past, insistently clamouring for Lebensraum under the duress of readiness to resort to war. Still the specter of war looms ominously. Never in human history have so many peoples experienced freedom. Yet human freedom itself is a crucial issue and is widely endangered. Indeed, by some peoples, it has already been gained and lost.

Peoples everywhere wish and long for peace and freedom in their simplest and clearest connotations: an end to armed conflict and to the suppression of the inalienable rights of man. In a single generation, the peoples of the world have suffered the profound anguish of two catastrophic wars; they have had enough of war. Who could doubt that the people of Norway – ever peaceful, still deeply wounded from an unprovoked, savage Nazi aggression – wish peace? Who could doubt that all of the peoples of Europe – whose towns and cities, whose peaceful countrysides, have been mercilessly ravaged; whose fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, have been slaughtered and maimed in tragic numbers – wish peace? Who could sincerely doubt that the peoples of the Western hemisphere – who, in the common effort to save the world from barbaric tyranny, came into the two world wars only reluctantly and at great sacrifice of human and material resources – wish peace? Who could doubt that the long-suffering masses of Asia and Africa wish peace? Who indeed, could be so unseeing as not to realize that in modern war victory is illusory; that the harvest of war can be only misery, destruction, and degradation?

If war should come, the peoples of the world would again be called upon to fight it, but they would not have willed it.

Statesmen and philosophers repeatedly have warned that some values – freedom, honour, self- respect – are higher than peace or life itself. This may be true. Certainly, very many would hold that the loss of human dignity and self-respect, the chains of enslavement, are too high a price even for peace. But the horrible realities of modern warfare scarcely afford even this fatal choice. There is only suicidal escape, not freedom, in the death and destruction of atomic war. This is mankind’s great dilemma. The well-being and the hopes of the peoples of the world can never be served until peace – as well as freedom, honour and self-respect – is secure.

The ideals of peace on earth and the brotherhood of man have been expounded by philosophers from earliest times. If human relations were governed by the sagacity of the great philosophers, there would be little danger of war, for in their collective wisdom over the centuries they have clearly charted the course to free and peaceful living among men.

Throughout the ages, however, man has but little heeded the advice of the wise men. He has been – fatefully, if not wilfully – less virtuous, less constant, less rational, less peaceful than he knows how to be, than he is fully capable of being. He has been led astray from the ways of peace and brotherhood by his addiction to concepts and attitudes of narrow nationalism, racial and religious bigotry, greed and lust for power. Despite this, despite the almost continuous state of war to which bad human relations have condemned him, he has made steady progress. In his scientific genius, man has wrought material miracles and has transformed his world. He has harnessed nature and has developed great civilizations. But he has never learned very well how to live with himself. The values he has created have been predominantly materialistic; his spiritual values have lagged far behind. He has demonstrated little spiritual genius and has made little progress toward the realization of human brotherhood. In the contemporary atomic age, this could prove man’s fatal weakness.

Alfred Nobel, a half-century ago, foresaw with prophetic vision that if the complacent mankind of his day could, with equanimity, contemplate war, the day would soon inevitably come when man would be confronted with the fateful alternative of peace or reversion to the Dark Ages. Man may well ponder whether he has not now reached that stage. Man’s inventive genius has so far outreached his reason – not his capacity to reason but his willingness to apply reason – that the peoples of the world find themselves precariously on the brink of total disaster.

If today we speak of peace, we also speak of the United Nations, for in this era, peace and the United Nations have become inseparable. If the United Nations cannot ensure peace, there will be none. If war should come, it will be only because the United Nations has failed. But the United Nations need not fail. Surely, every man of reason must work and pray to the end that it will not fail.

In these critical days, it is a high privilege and a most rewarding experience to be associated with the United Nations – the greatest peace effort in human history. Those who work in and with the organization, perhaps inevitably, tend to develop a professional optimism with regard to the prospects for the United Nations and, therefore, to the prospects for peace. But there is also a sense of deep frustration, which flows from the knowledge that mankind could readily live in peace and freedom and good neighbourliness if there were but a minimum of will to do so. There is the ever present, simple but stark truth that though the peoples long primarily for peace, they may be prodded by their leaders and governments into needless war, which may at worst destroy them, at best lead them once again to barbarism.

The United Nations strives to be realistic. It understands well the frailties of man. It is realized that if there is to be peace in the world, it must be attained through men and with man, in his nature and mores, just about as he now is. Intensive effort is exerted to reach the hearts and minds of men with the vital pleas for peace and human understanding, to the end that human attitudes and relations may be steadily improved. But this is a process of international education, or better, education for international living, and it is at best gradual. Men change their attitudes and habits slowly, and but grudgingly divorce their minds from fears, suspicions, and prejudices.

The United Nations itself is but a cross section of the world’s peoples. It reflects, therefore, the typical fears, suspicions, and prejudices which bedevil human relations throughout the world. In the delegations from the sixty member states and in the international Secretariat in which most of them are represented, may be found individual qualities of goodness and badness, honesty and subterfuge, courage and timorousness, internationalism and chauvinism. It could not be otherwise. Still, the activities of all are within the framework of a great international organization dedicated to the imperative causes of peace, freedom, and justice in the world.

The United Nations, inescapably, is an organization at once of great weakness and great strength.

Its powers of action are sharply limited by the exigencies of national sovereignties. With nationalism per se there may be no quarrel. But narrow, exclusively self-centered nationalism persists as the outstanding dynamic of world politics and is the prime obstacle to enduring peace. The international well-being, on the one hand, and national egocentrism, on the other, are inevitably at cross-purposes. The procedures and processes of the United Nations as a circumscribed international parliament are unavoidably complex and tedious.

The United Nations was established in the hope, if not on the assumption, that the five great powers would work harmoniously toward an increasingly better world order. The existing impasse between West and East and the resultant “cold war” were not foreseen by those who formulated the United Nations Charter in the spring of 1945 in the misleading, but understandably jubilant, atmosphere of war’s triumphant end. Nevertheless, the United Nations has exhibited a fortunate flexibility which has enabled it to adjust to the regrettable circumstances of the discord among the great powers and to continue to function effectively.

Reflecting the hopes and aspirations of all peoples for peace, security, freedom, and justice, the foundations of the United Nations are firmly anchored, and its moral sanctions are strong. It is served by a fully competent international Secretariat which is devoted to the high principles and purposes of the organization. At the head of this Secretariat is the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Trygve Lie1, a great son of Norway, and a man whose name will be writ large in the annals of world statesmanship and peacemaking. No living man has worked more persistently or courageously to save the world from the scourge of war than Trygve Lie.

In its short but turbulent five years, the United Nations, until the past few weeks, at least, has demonstrated a comforting ability to cope with every dangerous crisis that has erupted into violence or threatened to do so. It has never been easily done nor as well as might be hoped for, but the fact remains that it has been done. In these post-war years, the United Nations, in the interest of peace, has been called upon to eliminate the threat of local wars, to stop local wars already underway, and now in Korea, itself to undertake an international police action which amounts to full-scale war. Its record has been impressive. Its interventions have been directly responsible for checking and containing dangerous armed conflicts in Indonesia, Kashmir, and Palestine, and to only a lesser extent in Greece2.

That the United Nations has been able to serve the cause of peace in this way has been due in large measure to the determination of its members to reject the use of armed force as an instrument of national policy, and to the new techniques of international intervention which it has employed. In each instance of a threat to the peace, the United Nations projects itself directly into the area of conflict by sending United Nations representatives to the area for the purpose of mediation and conciliation.

It was as the head of a United Nations mission of this kind that Count Folke Bernadotte3 went to Palestine in the spring of 1948. On his arrival in the Near East, he found the Arabs and Jews locked in a bitter, bloody, and highly emotional war in Palestine. He was armed only with the strong demand of the United Nations that in the interest of world peace the Palestine problem must be settled by peaceful means.

In one of the most brilliant individual feats of diplomatic history, Count Bernadotte, within two weeks of his arrival on the scene of conflict, had negotiated a four weeks’ truce and the guns had ceased firing. In order to supervise that truce, he requested of the Secretary-General and promptly received an international team of civilian and military personnel, numbering some seven hundred men and women. The members of this compact and devoted United Nations “peace army” in Palestine, many of whom were from the Scandinavian countries and all of whom were unarmed, under the early leadership of Count Bernadotte wrote a heroic chapter in the cause of peacemaking4. Their leader, Bernadotte himself, and ten others, gave their lives in this effort. The United Nations and the peace-loving world must ever be grateful to them.

We who had the privilege to serve under the leadership of Count Bernadotte revere his name. He was a great internationalist, a warm-hearted humanitarian, a warrior of unflinching courage in the cause of peace, and a truly noble man. We who carried on after him were inspired by his self-sacrifice and were determined to pay him the one tribute which he would have appreciated above all others – the successful completion of the task which he had begun, the restoration of peace to Palestine.

In Korea, for the first, and it may be fervently hoped, the last time, the United Nations processes of peaceful intervention to settle disputes failed. They failed only because the North Korean regime stubbornly refused to afford them the chance to work and resorted to aggressive force as the means of attaining its ends. Confronted with this, the gravest challenge to its mandate to preserve the peace of the world, the United Nations had no reasonable alternative but to check aggressive national force with decisive international force. This it has attempted to do, and it was enabled to do so only by the firm resolve of the overwhelming majority of its members that the peace must be preserved and that aggression shall be struck down wherever undertaken or by whom5.

By virtue of recent setbacks to United Nations forces in Korea, as a result of the injection of vast numbers of Chinese troops into the conflict, it becomes clear that this resolve of its members has not been backed by sufficient armed strength to ensure that the right shall prevail. In the future, it must be the forces of peace that are overwhelming.

But whatever the outcome of the present military struggle in Korea in which the United Nations and Chinese troops are now locked, Korea provides the lesson which can save peace and freedom in the world if nations and peoples will but learn that lesson, and learn it quickly. To make peace in the world secure, the United Nations must have readily at its disposal, as a result of firm commitments undertaken by all of its members, military strength of sufficient dimensions to make it certain that it can meet aggressive military force with international military force, speedily and conclusively.

If that kind of strength is made available to the United Nations – and under action taken by the General Assembly this fall it can be made available – in my view that strength will never again be challenged in war and therefore need never be employed.

But military strength will not be enough. The moral position of the United Nations must ever be strong and unassailable; it must stand steadfastly, always, for the right.

The international problems with which the United Nations is concerned are the problems of the interrelations of the peoples of the world. They are human problems. The United Nations is entitled to believe, and it does believe, that there are no insoluble problems of human relations and that there is none which cannot be solved by peaceful means. The United Nations – in Indonesia, Palestine, and Kashmir – has demonstrated convincingly that parties to the most severe conflict may be induced to abandon war as the method of settlement in favour of mediation and conciliation, at a merciful saving of untold lives and acute suffering.

Unfortunately, there may yet be some in the world who have not learned that today war can settle nothing, that aggressive force can never be enough, nor will it be tolerated. If this should be so, the pitiless wrath of the organized world must fall upon those who would endanger the peace for selfish ends. For in this advanced day, there is no excuse, no justification, for nations resorting to force except to repel armed attack.

The world and its peoples being as they are, there is no easy or quick or infallible approach to a secure peace. It is only by patient, persistent, undismayed effort, by trial and error, that peace can be won. Nor can it be won cheaply, as the taxpayer is learning. In the existing world tension, there will be rebuffs and setbacks, dangerous crises, and episodes of violence. But the United Nations, with unshakable resolution, in the future as in the past, will continue to man the dikes of peace. In this common purpose, all states, irrespective of size, are vital.

The small nations, which constitute the overwhelming majority in its membership, are a great source of strength for the United Nations. Their desire for peace is deep seated and constant. The fear, suspicion, and conflict which characterize the relations among the great powers, and the resultant uncertainty, keep them and their peoples in a state of anxious tension and suspense. For the relations among the great powers will largely determine their future. A third world war would quickly engulf the smaller states, and many of them would again provide the battlefields. On many of them, now as before, the impact of war would be even more severe than upon the great powers. They in particular, therefore, support and often initiate measures designed to ensure that the United Nations shall be increasingly effective as a practical instrumentality for peace. In this regard, the Scandinavian countries contribute signally to the constructive effort of the United Nations.

One legacy of the recent past greatly handicaps the work of the United Nations. It can never realize its maximum potential for peace until the Second World War is fully liquidated. The impasse between West and East has prevented the great powers from concluding the peace treaties which would finally terminate that last war6. It can be little doubted that the United Nations, if called upon, could afford valuable aid toward this end. At present, the United Nations must work for future peace in the unhappy atmosphere of an unconcluded great war, while precluded from rendering any assistance toward the liquidation of that war. These, obviously, are matters of direct and vital concern to all peace-loving nations, whatever their size.

At the moment, in view of the disturbing events in Korea and Indo-China7, the attention of a fearful world is focused on Asia, seeking an answer to the fateful question “peace or war?” But the intrinsic importance of Europe in the world peace equation cannot be ignored. The peace of Europe, and therefore of the world, can never be secure so long as the problem of Germany remains unsolved.

In this regard, those who at the end of the last war were inclined to dismiss Europe as a vital factor in reckoning the future security and prosperity of the world, have had to revise their calculations. For Europe, grievously wounded though it was, has displayed a remarkable resiliency and has quickly regained its place in the orbit of world affairs.

But Europe, and the Western world generally, must become fully aware that the massive and restive millions of Asia and Africa are henceforth a new and highly significant factor in all peace calculations. These hitherto suppressed masses are rapidly awakening and are demanding, and are entitled to enjoy, a full share in the future fruits of peace, freedom, and security.

Very many of these millions are experiencing a newfound freedom. Many other millions are still in subject status as colonials. The aspirations and demands of those who have achieved freedom and those who seek it are the same: security, treatment as equals, and their rightful place in the brotherhood of nations.

It is truer today than when Alfred Nobel realized it a half-century ago, that peace cannot be achieved in a vacuum. Peace must be paced by human progress. Peace is no mere matter of men fighting or not fighting. Peace, to have meaning for many who have known only suffering in both peace and war, must be translated into bread or rice, shelter, health, and education, as well as freedom and human dignity – a steadily better life. If peace is to be secure, long-suffering and long-starved, forgotten peoples of the world, the underprivileged and the undernourished, must begin to realize without delay the promise of a new day and a new life.

In the world of today, Europe, like the rest of the West, is confronted with the urgent necessity of a new orientation – a global orientation. The pre-war outlook is as obsolete as the pre-war world. There must be an awakening to the incontestable fact that the far away, little known and little understood peoples of Asia and Africa, who constitute the majority of the world’s population, are no longer passive and no longer to be ignored. The fury of the world ideological struggle swirls about them. Their vast numbers will prove a dominant factor in the future world pattern of life. They provide virgin soil for the growth of democracy, but the West must first learn how to approach them understandingly and how to win their trust and friendship. There is a long and unsavory history of Western imperialism, suppression, and exploitation to be overcome, despite the undenied benefits which the West also brought to them. There must be an acceleration in the liquidation of colonialism. A friendly hand must be extended to the peoples who are labouring under the heavy burden of newly won independence, as well as to those who aspire to it. And in that hand must be tangible aid in generous quantity – funds, goods, foodstuffs, equipment, technical assistance.

There are great issues demanding resolution in the world: the clash of the rather loosely defined concepts and systems of capitalism and communism; the radically contrasting conceptions of democracy, posing extreme views of individualism against extreme views of statism; the widespread denials of human rights; the understandable impatience of many among some two hundred million colonial peoples for the early realization of their aspirations toward emancipation; and others.

But these are issues which in no sense may be considered as defying solution. The issue of capitalism versus communism is one of ideology which in the world of today cannot, in fact, be clearly defined. It cannot be clearly defined because there are not two worlds, one “capitalist” and one “communist”. There is but one world – a world of sharp clashes, to be sure – with these two doctrines at the opposite ideological poles. In between these extremes are found many gradations of the two systems and ideologies.

There is room in the world for both capitalism and communism and all gradations of them, providing only that neither system is set upon pursuing an aggressively imperialistic course.

The United Nations is opposed to imperialism of any kind, ideological or otherwise. The United Nations stands for the freedom and equality of all peoples, irrespective of race, religion, or ideology. It is for the peoples of every society to make their own choices with regard to ideologies, economic systems, and the relationship which is to prevail between the state and the individual. The United Nations is engaged in an historic effort to underwrite the rights of man. It is also attempting to give reassurance to the colonial peoples that their aspirations for freedom can be realized, if only gradually, by peaceful processes.

There can be peace and a better life for all men. Given adequate authority and support, the United Nations can ensure this. But the decision really rests with the peoples of the world. The United Nations belongs to the people, but it is not yet as close to them, as much a part of their conscious interest, as it must come to be. The United Nations must always be on the people’s side. Where their fundamental rights and interests are involved, it must never act from mere expediency. At times, perhaps, it has done so, but never to its own advantage nor to that of the sacred causes of peace and freedom. If the peoples of the world are strong in their resolve and if they speak through the United Nations, they need never be confronted with the tragic alternatives of war or dishonourable appeasement, death, or enslavement.

Amidst the frenzy and irrationality of a topsy-turvy world, some simple truths would appear to be self-evident.

As Alfred Nobel finally discerned, people are never deterred from the folly of war by the stark terror of it. But it is nonetheless true that if in atomic war there would be survivors, there could be no victors. What, then, could war achieve which could not be better gained by peaceful means? There are, to be sure, vital differences and wide areas of conflict among the nations, but there is utterly none which could not be settled peacefully – by negotiation and mediation – given a genuine will for peace and even a modicum of mutual good faith.

But there would appear to be little hope that efforts to break the great power impasse could be very fruitful in the current atmosphere of fear, suspicion, and mutual recrimination. Fear, suspicion, and recrimination in the relations among nations tend to be dangerously self-compounding. They induce that national hysteria which, in its rejection of poise and rationality, can itself be the fatal prelude to war. A favourable climate for peaceful negotiation must be created and can only be created by painstaking, unremitting effort. Conflicting parties must be led to realize that the road to peace can never be traversed by threatening to fight at every bend, by merely being armed to the teeth, or by flushing every bush to find an enemy. An essential first step in a civilized approach to peace in these times would call for a moratorium on recrimination and reproach.

There are some in the world who are prematurely resigned to the inevitability of war. Among them are the advocates of the so-called “preventive war”, who, in their resignation to war, wish merely to select their own time for initiating it. To suggest that war can prevent war is a base play on words and a despicable form of warmongering. The objective of any who sincerely believe in peace clearly must be to exhaust every honourable recourse in the effort to save the peace. The world has had ample evidence that war begets only conditions which beget further war.

In the final analysis, the acid test of a genuine will to peace is the willingness of disputing parties to expose their differences to the peaceful processes of the United Nations and to the bar of international public opinion which the United Nations reflects. It is only in this way that truth, reason, and justice may come to prevail over the shrill and blatant voice of propaganda; that a wholesome international morality can be cultivated.

It is worthy of emphasis that the United Nations exists not merely to preserve the peace but also to make change – even radical change – possible without violent upheaval. The United Nations has no vested interest in the status quo. It seeks a more secure world, a better world, a world of progress for all peoples. In the dynamic world society which is the objective of the United Nations, all peoples must have equality and equal rights. The rights of those who at any given time may be in the minority – whether for reasons of race, religion, or ideology – are as important as those of the majority, and the minorities must enjoy the same respect and protection. The United Nations does not seek a world cut after a single pattern, nor does it consider this desirable. The United Nations seeks only unity, not uniformity, out of the world’s diversity.

There will be no security in our world, no release from agonizing tension, no genuine progress, no enduring peace, until, in Shelley’s fine words, “reason’s voice, loud as the voice of nature, shall have waked the nations”.

* The laureate delivered this lecture in the Auditorium of the University of Oslo. The text, taken from Les Prix Nobel en 1950, is that of the full version of the lecture; collation with the tape recording shows that it was considerably shortened in delivery.

1. Trygve Lie (1896-1968), prominent Norwegian lawyer and statesman; first UN secretary-general (1946-1953).

2. For accounts of these conflicts and of others in the early years of the UN, see Clark M. Eichelberger, UN: The First Fifteen Years (New York: Harper, 1960).

3. Count Folke Bernadotte (1895-1948), Swedish humanitarian, president of the Swedish Red Cross.

4. See Ralph Hewins, Count Folke Bernadotte: His Life and Work (London: Hutchinson, 1950).

5. North Korea invaded South Korea in June, 1950, and was declared an aggressor by the UN Security Council; UN troops (a unified command under the U.S.) were sent to repel the attack after North Korea ignored the UN call for a cessation of

hostilities; in November, 1950, Chinese Communists entered the war, which continued until an armistice was signed in July, 1953.

6. Nor have they been concluded as of 1971.

7. Indo-China’s struggle for emancipation from French rule, successful in 1954 had reached a critical stage at the time of the laureate’s lecture.

** Disclaimer

Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organizations and individuals with regard to the supply of audio files. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Ralph Bunche – Other resources

Links to other sites

Ralph Bunche – An American Odyssey from PBS, Public Broadcasting Service

Ralph Bunche Centenary 2003-2004 from Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies

A Centenary Celebration of Ralph J. Bunche from University of California

Ralph Bunche: UN Mediator in the Middle East, 1948-1949

Ralph Bunche: UN Mediator in the Middle East, 1948-1949

by Asle Sveen*

This article was published on 9 December 2006.

“I have a bias in favour of both Arabs and Jews in the sense that I believe that both are good, honourable and essentially peace-loving peoples, and are therefore as capable of making peace as of waging war …” – Ralph Bunche, 19491

Nobel Peace Prize Laureate

In 1950 the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to the first non-white person, the African-American and United Nations (UN) official Ralph Bunche. He received the Peace Prize for his efforts as mediator between Arabs and Jews in the Israeli-Arab war in 1948-1949. These efforts resulted in armistice agreements between the new state of Israel and four of its Arab neighbours: Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

Two members of the Norwegian parliament nominated Ralph Bunche for the Nobel Peace Prize. Both had connections to the newly founded United Nations. One was Norway’s first UN ambassador, and the other was a member of the Norwegian UN delegation. The nomination stated: “Although it can not be said to be Dr. Bunche’s merit, but the development process itself that made the parties end the hostilities, there can be no doubt that it is Dr. Bunche’s merit that the challenging negotiations over a ceasefire were brought to a positive result in a relatively short time”.

The nominators had several motives. Awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to Bunche “would thereby not only honour him personally, but express trust and faith in the ability of the United Nations to solve international disputes by way of mediation between the parties”. Furthermore, the nominators could not “neglect to mention that giving the Nobel Peace Prize to a member of the coloured race is a boost to peace in itself”. Thus the Peace Prize was meant to strengthen the UN and to serve as an initiative against racism as well as to honour Ralph Bunche.

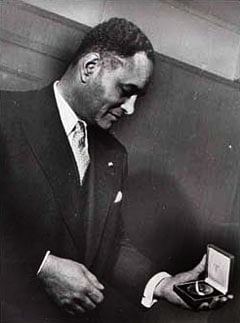

Ralph Bunche studying his Nobel Peace Prize medal after receiving it in Oslo, Norway on 10 December 1950.

Photo: Courtesy of Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies, City University of New York, Graduate Center

Family Background and Education

Ralph Bunche was born in 1903, in the industrial city of Detroit, Michigan, in the United States. Most of his ancestors were descendants of black slaves, but there was also Irish heritage in his family. After his mother’s death in 1917, Bunche moved with his grandmother to Los Angeles, California. She was a light-skinned woman who could almost pass for white, but she was proud of her black origin and raised Ralph to be proud of his race, work hard and get the best education he could.

It was in Los Angeles that Bunche had his first real encounter with racial discrimination. Although an excellent high-school student, he was excluded from the most popular students’ association. Nevertheless, he wrote for the campus newspaper, was president of the debating team and became a star basketball player. In 1927 he graduated from the University of Los Angeles (UCLA) as a Political Science major and valedictorian of his class.

Earning a master’s degree at Harvard University, Ralph Bunche took a teaching position at Howard University in Washington, where he founded the school’s Political Science Department.

Ralph Bunche obtained a doctorate in French Colonial Policy as the first African-American to earn a doctorate in Political Science. He lived and studied for several months in different parts of Africa, and was appalled by the striking poverty he observed and the bad treatment of Africans by the colonial administrations. His studies extended to include the rights of all peoples without self-government, and he developed a profound knowledge of trusteeships and the question of decolonisation.

Struggle Against Racism

In the 1930s Bunche became a recognized authority on race relations, and for a while was attracted to Marxist analyses that emphasised economic explanations for poverty and racism. He was one of the founders of the radical National Negro Congress, which had the aim of cooperation on social issues and the creation of mutual solidarity across the colour bar.

In 1939 Bunche joined the staff of the Swedish social scientist Gunnar Myrdal, who studied American racial segregation. Myrdal disagreed with the Marxist theory that black Americans could only obtain liberation and equality through class struggle in cooperation with the white working class. In contrast, he believed that a large part of the white population was so infused with racism that the strategy of the African-Americans ought to be to get the federal government to practise the spirit and principles of freedom embodied in the Constitution of the United States for the whole American populace. Bunche was strongly influenced by Myrdal, and in 1940 he left the National Negro Congress after it had been taken over by the American Communist Party.

United States Official

In December 1941, the United States was brought into the Second World War by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Shortly before this dramatic event, Bunche joined the staff of the American intelligence service as an expert on colonial areas. His job was to provide the American forces with useful information for operations in Africa and Asia. Through hard work and excellent memorandums Bunche was soon moved to positions of higher responsibility, and in 1944 he became the first African-American to hold a top position in the US State Department, with responsibility for colonial issues.

Assistant to the Special Committee on Palestine

In 1945 the Second World War was brought to an end and the United Nations was founded. The first UN Secretary-General, the Norwegian Trygve Lie, asked Bunche to join the UN. Bunche went into the UN service the following year to work with the question on decolonisation. In 1947 Lie made him assistant to a special committee on Palestine.

During this time, a conflict was brewing in the Middle East between the British, Jews and Arabs over Jewish demands for a separate state. At a special session of the UN in May 1947, Jewish delegates argued that European anti-Semitism and the Nazi extermination of six million Jews during the Second World War made the creation of a Jewish state absolutely necessary. An Arab representative countered that the Arabs of Palestine should not suffer for the crimes of Hitler.2 Finally, Britain left the UN in charge of the Middle East conflict, which was marked by increasing bitterness and extremism, and a UN Committee was formed to find solutions to the problems.

The committee travelled for six weeks, conducting interviews in Palestine, Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, as well as visiting Jews in displaced-person camps in Europe. Many Arabs refused to talk to the committee, claiming that the UN had no right to give away any part of their land. The most extremist Jews wanted to take all of Palestine as well as areas on the east bank of Jordan, while the moderates were prepared to accept a partition of Jewish and Arab territories.

Bunche did not find it easy to work with the members of the UN Committee, which he characterised as the worst group he had ever worked with because of internal strife and disagreements. Finally, the majority of the UN Committee proposed a partition of Palestine into two independent Jewish and Palestinian states. Jerusalem was to be governed by the UN to guarantee access for Jews, Christians and Muslims to all their holy sites. The minority in the committee wanted a federal state, with separate provinces for Arabs and Jews, and with Jerusalem as a common capital. Although Ralph Bunche had drafted both proposals, he was frustrated. In a letter to his wife, he wrote that the Palestine problem was the intractable sort that had no possible satisfactory solutions.

In the autumn of 1947, a majority in the UN, including the United States and the Soviet Union, adopted the partition plan. The Arab and Muslim delegations marched out in protest, while Jews worldwide jubilantly hailed the result.

Assistant to Count Folke Bernadotte

On 14 May 1948, the last British ship sailed from Palestine. Jews celebrated the creation of the state of Israel, but soon after Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia declared war on the new state. The Israeli army, which was better trained and equipped than its opponents, soon had the upper hand in the war, conquering land beyond the areas allotted to them in the UN partition plan. The war made Arab families flee parts of Palestine occupied by Jewish forces, and during the fighting as many as 700,000 Palestinians fled their homes, creating a large-scale refugee problem.

The Security Council appointed the Swedish Count Folke Bernadotte as mediator to promote a peaceful adjustment of the situation in Palestine. As the head of the Swedish Red Cross, Count Bernadotte had successfully negotiated the release of Danish and Norwegian prisoners from the Nazi concentration camps during the last weeks of World War II in Europe. Trygve Lie asked Ralph Bunche to accompany Bernadotte to the Middle East as Chief Representative of the Secretary-General. Lie saw Bunche as the man who understood the conflict and who was able to draft compromise proposals which could bring the fighting to a halt.

Bernadotte and Bunche were shuttled between Jerusalem and the Arab capitals in the Count’s white plane to put a stop to the war. In June the parties accepted a ceasefire agreement drawn up by Bunche.

Count Bernadotte moved his headquarters to the island of Rhodes to have peaceful and neutral surroundings. He believed that the partition plan needed revisions to ensure Arab acceptance. At Rhodes, Bernadotte and Bunche worked out a draft that was later known as the Bernadotte Plan. This plan proposed a union between Jordan and Palestine and the creation of an independent Israeli state. The proposal included Jerusalem in an Arab state with autonomy for the Jewish minority. In addition, Palestinian refugees should be allowed to return to their homes in Israeli-occupied territory or receive compensation for the losses of their homes.

The draft was designed for internal discussion but its content was leaked. As a result, the draft had to be published as a document of the UN Security Council. Both Palestinians and Jews rejected the plan, and the Lehi group, an extremist Jewish faction, disliked it so much that it set out to assassinate the charismatic Bernadotte before he could influence the UN. The Lehi group, which included future Israeli Prime Minister Yitzak Shamir, regarded Bernadotte as an agent of the British government, and wanted him dead.3 Bunche was scheduled to meet Bernadotte in Jerusalem, from where they would proceed to put the new partition proposal before the UN General Assembly. Several delays prevented Bunche from reaching the Jerusalem rendezvous point on time, and Bernadotte instead brought a French UN officer to accompany him to his meeting in the city that day. En route they were stopped by armed men in Israeli uniforms at the Mandelbaum gate in Jerusalem. One of them pointed his machine gun into the car and fired, killing both Bernadotte and the French officer — the latter probably wrongly taken to be Bunche. Meanwhile Bunche, who was supposed to have been in the car, arrived at the rendezvous point half an hour after the Count had left.

|

| Ralph Bunche (right) and Count Folke Bernadotte boarding a United Nations plane. Photo: Courtesy of Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies, City University of New York, Graduate Center |

Leader of the UN Palestine Mission

When news of Bernadotte’s death reached the UN, Trygve Lie immediately phoned Bunche and asked him to succeed Bernadotte and carry on the mediation effort. Despite awareness of the personal danger posed by the role, Bunche did not hesitate to accept Lie’s request. Bunche travelled to Paris, where he met with UN representatives to discuss the new borders between Jews and Arabs that he and Bernadotte had proposed.

In the meantime, fighting in Palestine broke out again between Israeli and Egyptian forces, with Israel on the offensive conquering new ground. The General Assembly of the UN gave up the Bernadotte Plan and the Security Council in a resolution originally drafted by Bunche, demanded that the parties in the conflict should establish an armistice through negotiations.

After weeks of toil, Bunche was able to bring the Israelis and Egyptians to the negotiating table on Rhodes in January 1949. The Arab countries initially refused to negotiate directly with Israel, but on the isle of Rhodes Bunche managed to persuade the Egyptians and Israelis to sit together at the negotiating table, and discuss the Middle East problems face to face.

The negotiations began with Israel and Egypt in January 1949. Through discretion, patience and humour Bunche won the confidence of the negotiating parties. He formulated compromise proposals and was willing to work for months to come to an agreement. With Bernadotte’s fate in mind, Bunche made the negotiators agree to total secrecy; the press and Security Council were only to receive official press reports. Hard negotiations led to the signing of a truce by both parties by the end of February 1949. As Egypt was the leading Arab nation, it paved the way for later agreements between Israel and Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

An Agreement in Favour of Israel?

Recent research has shown that the UN Secretary-General Trygve Lie and the United States government played a much more decisive role in the negotiations than was otherwise known before.4 On several occasions Bunche asked President Truman and Lie for help to prevent a breakdown in the negotiations, and information that was meant solely for the UN was passed on to the United States delegation by Secretary Lie. Like most Norwegian Social Democrats, Lie sympathised strongly with the Jewish position, and President Truman supported the Jewish case because his advisers informed him that the Jewish votes in the United States were both important for his re-election in 1948 and for the Democratic Party in the future. As both Lie and Truman were biased in favour of Israel, pressure to compromise was mainly applied to the Egyptian delegation, and the final agreement was more beneficial to Israel than the Arab countries, despite Bunche’s efforts to achieve impartiality. In fact Bunche’s diary shows that he was often annoyed with the behaviour of the Jewish delegates and had sympathy for the demands of the Egyptian delegation.

With the conclusion of the agreement between Israel and Syria on 20 July 1949, the Rhodes armistice negotiations were completed – Israel was recognized by the world community as an independent state within new borders, and was admitted as a member of the UN.

Personally, Bunche believed that the Palestinian Arabs were the big losers in the conflict, and, in fact, the agreements sealed the fate of the UN’s plan for an independent Palestinian state. The Israelis kept almost all the land they had conquered. Israel had expanded from the UN-allocated 55% of British ruled Palestine to 79%. Jordan and Egypt took what was left for the Palestinian Arabs. The armistice agreements were intended as the basis for peace negotiations within a year, but these never took place. Although the UN and the United States called for the rights of the Palestinian refugees to return to their homes, this never happened. The fate of the Palestinian refugees remained an unsolved problem.

The Nobel Peace Prize

When the news came that Bunche had won the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize, he considered declining it because, in his opinion, representatives of the UN ought not to be rewarded with prizes for their work for peace. But Trygve Lie insisted that he receive the Peace Prize – the UN needed all the publicity it could get.

The choice of Bunche as Nobel Peace Prize Laureate was well received the world over. In Sweden, it was seen as an indirect tribute to Folke Bernadotte. In Norway, a newspaper wrote that the prize was a message to non-white people of the world. Only the Soviet press was dissatisfied. One article branded Bunche as an ‘Uncle Tom’ – a good-natured black who lent himself to the efforts of the American authorities to keep the non-white population down.

By the time the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Bunche, the Korean War has started, with the United Nations as a participant. In his Nobel Lecture in Oslo, Bunche stressed that the UN was the greatest peace effort in human history, but it should be allowed to build an international military force to be deployed against aggressors violating the UN Charter. He also pointed to the fact that millions of people in Africa and Asia were poor and oppressed and that the West, in order to promote democracy, must support the basic creed of the UN that all peoples must have equality and equal rights.

Later Years

Bunche continued working for the United Nations under the Secretary-Generals Dag Hammarskjöld and U Thant. In the United States he supported the growing Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, and marched and spoke together with the Nobel Peace Prize Laureate of 1964, Martin Luther King, Jr.

Bunche and U Thant tried to put an end to the Vietnam War and establish lasting peace in the Middle East, but they suffered many setbacks. Bunche felt that the Six-Day War of 1967 between Israel and the Arab states ruined almost all the détente he had managed to establish in the region.

When Ralph Bunche died in 1971, the United Nations General Assembly paid its final tribute to him with one minute of silence.

Bibliography

Brian Urquhart: Ralph Bunche. An American Life. (New York, Norton, 1993).

Charles P. Henry: Ralph Bunche. Model Hero or American Other? (New York University Press, 1999).

Ingrid Næser: Right Versus Might. A Study of the Armistice Negotiations between Israel and Egypt in 1949. Dissertation in History. University of Oslo. Spring 2005.

Øivind Stenersen, Ivar Libæk, Asle Sveen: The Nobel Peace Prize. One Hundred Years for Peace. (Cappelen, Oslo, 2001).

Irwin Abrams: The Nobel Peace Prize and the Laureates. An illustrated biographical history 1901-2001. (Science History Publications/USA 2001).

Martin Gilbert: Israel. A history. (Black Swan UK 1998).

* Asle Sveen (1945 -) obtained his Master in History at the University of Oslo in 1972. He has more than twenty years of experience as teacher in history, social sciences and Nordic languages in senior secondary schools in Norway. Since 1983 he has written textbooks in history and social sciences for junior and senior secondary levels in the Norwegian school system. Asle Sveen is also author of four historical novels for young people, and he has been a researcher both at the Institute for Teaching and School Development, University of Oslo and at the Norwegian Nobel Institute. In 2001 he published “The History of the Nobel Peace Prize Through 100 Years” with two other Norwegian historians. He also worked as an adviser of the project group that developed the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo, which opened in 2005.

1. Henry, Charles P: Ralph Bunche. Model Negro or American Other? New York/London: New York University Press, 1999, p. 142.

2. Martin Gilbert: Israel. A history. p. 144. Black Swan 1998. The opinion was put forward by Iraq’s representative, Dr Fadhil Jamail.

3. Ingrid Næser: Right Verus Might. Dissertation in history. Oslo 2005, p 29. The name of the man who probably shot Bernadotte is known, but despite the demands of the Swedish Foreign Ministry for an investigation, no Israeli government has ever tried anyone for the murder.

4. Næser, pp. 105-110. In the conclusion of her dissertation Næser claims that the armistice agreement between Israel and Egypt was dictated by Israel through Trygve Lie and President Truman, and that Bunche played “the role of an errand boy” (p. 110).

First published 9 December 2006

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Gunnar Jahn*, Chairman of the Nobel Committee

Dr. Ralph Bunche was born forty-six years ago in Detroit in the United States. So today he is still a young man and indeed, along with Mr. Carl von Ossietzky, the youngest to be awarded the Peace Prize. Consequently, while most laureates have left their best years behind them, Dr. Bunche can still look forward to a long period of active life. At the same time he can also look back on years of persevering toil devoted to the unremitting campaign to develop, as he says, man’s ability to live in peace, harmony, and mutual understanding with his fellows.

The life story of Dr. Bunche is like that of many another American youth. Born and brought up in difficult circumstances, he had to go to work at an early age, becoming an errand boy at seven, and at twelve working long hours in a bakery, often until eleven or twelve o’clock at night. It was at this time that both of his parents died, and his old grandmother Nana took him and the other children to Los Angeles. Here young Ralph’s life was divided between school and work, for he had to work in order to live. But again Ralph Bunche was no exception, for, as he recalls, seventy percent of the students at the University of California were obliged to do the same. Such a life can bee hard on the young, but it can also serve to develop the strength of character necessary for making one’s way in life and meeting the problems one faces.

In 1927 Bunche passed his examinations at the University of Califomia, and in that same year started his studies at Harvard where, in 1934, he took his doctorate in political science. From 1928 until 1938 he was an instructor, and from 1938 until 1941 a professor, at Howard University in Washington

It was during these years that Bunche began to study colonial and racial problems. In 1936 he received a grant from the Social Science Research Council to examine colonial policy and the position of non-European peoples in South Africa. But before setting out for Africa, where he was to stay in Cape Town and later visit the African tribes, he prepared himself for the work ahead by study in London.

Bunche became one of Gunnar Myrdal‘s closest collaborators in his study of the American Negro1. He soon caught the attention of the American administration which, in 1941, gave him a post in the Office of Strategic Services as an expert in colonial affairs. Later, in 1944, he was appointed territorial specialist in colonial affairs under the State Department, and in 1945 became head of this division. He was at this time, as he himself points out, the first Negro to reach a position of such responsibility in the American administration. On repeated occasions he was sent as an official representative to international conferences: Dumbarton Oaks in 1944, the International Labor Conference in Philadelphia in 1945, the Constituent Assembly of the United Nations in San Francisco the same year. He was also a member of the United States delegation to the United Nations conference in London in 1945 and in 1946, as well as being among the representatives to the 1946 ILO Conference in Paris. It was in 1946 also that he was appointed director of the Trusteeship Department of the United Nations Secretariat.

These are the highlights of his remarkable career. But they give little insight into the man himself.

For Bunche, as for most of us, the early years – before we acquire the knowledge and experience that life and work give – were the formative ones. Looking back on his childhood, Bunche can remember no time when his family lived in conditions other than those of extreme poverty. But it was not poverty which made him the man we know today; for in the midst of this poverty was that highly gifted woman, his grandmother Nana. He tells of his childhood, when his grandmother and her four adult children, with their families, all lived under the same roof. It was a closely knit, matriarchal family, in which the grandmother was the dominant personality. A woman who had been born into slavery, she must have been a truly extraordinary person, and she unquestionably contributed more than anyone else to the molding of young Ralph’s character.

«But life was no idyll», says Bunche. «I was learning what it meant to be a Negro, even in an enlightened Northern city.»

«But», he continues later, «I wasn’t embittered by such experiences, for Nana had taught me to fight without rancor. She taught all of us to stand up for our rights, to suffer no indignity, but to harbor no bitterness toward anyone, as this would only warp our personalities. Deeply religious, she instilled in us a sense of personal pride strong enough to sustain all external shocks, but she also taught us understanding and tolerance.»2

It was a valuable heritage that Nana bequeathed to Bunche, one which was to help him enormously throughout his life. He, in turn, has tried to pass it on to his own children. He says:

«In rearing my children I have passed on the philosophy that Nana taught me as a youngster… The right to be treated as an equal by all other men, she said, is man’s birthright. Never permit anyone to treat you otherwise. Who, indeed, is a better American, a better protector of the American heritage, than he who demands the fullest measure of respect for those cardinal principles on which our society is reared? Nana told us that there would be many and great obstacles in our paths and that this was the way of life. But only weaklings give up in the face of obstacles. Be honest and frank with yourself and the world at all times, she said. Never compromise what you know to be the right. Never pick a fight, but never run from one if your principles are at stake. Go out into the world with your head high, and keep it high at all times.»3

Step out into the world with your head high, fight for what is right, but show understanding and tolerance for others – what valuable advice for a young man to take with him when he leaves his childhood home! These words were deeply engraved in the mind of Ralph Bunche and fortified him for the challenges that lay ahead.

As I have already mentioned, Bunche took up the study of racial and colonial problems early in his career. In a book published in 1936, under the title A World View of Race, he exposed all the unscientific nonsense promulgated about races, nonsense which has become a convenient and dangerous weapon in the hands of unscrupulous politicians and statesmen, as we know from Hitler’s Germany. He also analyzed French and British colonial policies which, however different they may be, have not allowed the natives an opportunity to develop their potential. He sees the racial problem as part and parcel of the much greater problem of the class war, the war between those who have and those who have not. This may rightly be called an oversimplification, and in later books he broadens his view of man and society, but we still find him returning time and time again to the opinion that the disparity between the standard of living in prosperous countries and that in underdeveloped countries is a source of unrest and a potential threat to peace.

In an essay he wrote in 1947, Human Relations in a Modern World, he outlines the problems of our time. He contrasts man as a free individual with man as a member of a group. «In my opinion», he writes, «there is nothing in man’s nature which makes it impossible for him to live in peace with his fellowmen. Most of us, I believe, would be quite tractable if the pressures exerted by groups or by society would give us the chance. But relations between people are never governed by individuals, for the individual is to a great extent a product of the group to which he belongs and is subordinated to the group in all important questions. The individual in the mass is but a reflection of this group. And so the relations between groups and countries constitute one of the most critical problems of our time.»

And he says: «We can achieve understanding and brotherhood between men only when the peoples of different nations feel that what unites them is a common goal which must be quickly attained.» Bunche himself has a strong faith in man: «I am firmly convinced that ordinary men everywhere are ready to accept the ideals inherent in understanding and brotherhood among men, if only they are given the chance. But before this can happen, men must be sure that they will not become victims of unstable economic conditions, they must not be forced to take part in ruthless and harmful competition in order to survive, and they must be free from the constant threat of being obliterated in a future war. But it is more important still that men be able to shape their ideals free from the influence of petty and narrow-minded men who still in many countries exploit these ideals to further their own ends… But an indolent, complacent, and uninformed people can never feel secure or free.»

One can say: This is a faith, a belief. But who can do man’s work in life without faith? In Bunche this faith is coupled with a profound knowledge of men and of their conditions of life, both of which he clearly demonstrated as a mediator in Palestine.

Until 1948 Bunche’s activities had been confined to scientific and administrative work. However, when on May 20, 1948, Folke Bernadotte4 was appointed by the United Nations as mediator in the Palestine conflict, Bunche became his closest collaborator. The two men worked together until Bernadotte’s assassination on September 17 of the same year. Bunche was then named as his successor by the UN and continued the work of mediation in Palestine until August of 1949.

The two men who met in 1948 to undertake this common task could hardly have been more unlike. On the one hand, Folke Bernadotte, grandson of King Oscar II of Sweden and nephew of Sweden’s reigning monarch5, steeped in all the traditions of a royal family; on the other, Bunche, whose grandmother had been born in slavery, who had been brought up in poverty, who was an entirely self-made man.

Folke Bernadotte was scantily informed on the Palestine conflict. «My knowledge of the situation in Palestine was very superficial», he confessed. He had not worked with international problems until the latter part of the war, when he succeeded in negotiating the release of Danish and Norwegian prisoners from German prison and concentration camps. Bunche, head of the Trusteeship Department of the United Nations, had back of him an education and training directed precisely at recognizing and understanding the problems raised by international disputes.

Yet the two men had one thing in common: they both believed in their mission. Bunche at one time speaks of the qualities mediators should possess: «They should be biased against war and for peace. They should have a bias which would lead them to believe in the essential goodness of their fellowman and that no problem of human relations is insoluble. They should be biased against suspicion, intolerance, hate, religious and racial bigotry.»6

Both men were well endowed with such qualities, and indeed they had to be richly endowed to have hope of accomplishing the difficult task which confronted them in Palestine.

The Palestine problem had occupied the United Nations for a long time. It would take too much time to go into the background of the dispute, whose origins date back to the end of the First World War. In 1948 matters had reached the stage of a proposal put forward in the United Nations for a solution embodying the creation of a Jewish state. But this suggestion met determined resistance, and the whole of 1948 had been a year of constant skirmishes, if not of open war.

When the British mandate over Palestine came to an end on May 15, 1948, there was actually open war already between the Arab States and the Jews. The Truce Commission which was sent to Palestine in April was unable t o make any headway, and it was in these circumstances that the United Nations on May 20 appointed Bernadotte as a mediator whose first task was to secure a truce.

Bernadotte and Bunche arrived in Palestine on May 28 and succeeded in obtaining a four-week truce, lasting from June 11 until July 9. This was a first step forward. But on July 11 hostilities broke out again, and on the sixteenth the Security Council ordered a cease-fire and an extension of the truce from July 18. This order came after Bernadotte had personally laid the case before the Security Council. It is noteworthy that this was the first time that the Security Council had given such an order.

Then came Bernadotte’s assassination on September 17 and, as already mentioned, the Security Council appointed Bunche to succeed him as mediator.

The initial cease-fire had been difficult to secure, and there can be no doubt that its swift arrangement was possible only through the personal efforts of Bernadotte and Bunche. The latter comments7: «This truce was a one-man feat. Count Bernadotte was a man of great urbanity and indefatigable energy. He was a true internationalist at heart and was devoted to the cause of peace. He was fearless. In a remarkably short period, he had won the respect and confidence of both Arabs and Jews.»

The truce which began on July 18 was broken again in the middle of October. It was then that Bunche took the daring step of proposing to the Security Council that it should order a cease-fire to allow both parties to try to reach agreement on an armistice as a preliminary to a final settlement of the relations between Palestine and the Arab States. His proposal was approved by the Security Council on the sixteenth of November.

The proposal was, as I have said, a daring one, for an armistice is more than a cease-fire; an armistice, in the accepted meaning of the word, is in effect a preliminary to peace. But it turned out that Bunche had judged the situation correctly. And so began the negotiations between the Arab States and Palestine, negotiations which dragged on for eleven months, making the greatest demands on the mediator. Bunche has himself described the difficulties in the Colgate Lectures in Human Relations, 1949: suspicion on both sides, with neither wanting to meet the other. The Arabs did not want to sit at the same table with the Jews; so he was compelled to negotiate separately with each side, constantly having to clear away the mutual mistrust. It must be borne in mind that this was not mediation between two parties but between Palestine on the one hand and seven Arab States on the other, and that agreements had to be concluded separately with each of the seven.

By exercising infinite patience, Bunche finally succeeded in persuading all parties to accept an armistice. When asked how he managed it, he gave the following reply:

«Like every Negro in America, I’ve been buffeted about a great deal. I’ve suffered many disillusioning experiences. Inevitably, I’ve become allergic to prejudice. On the other hand, from my earliest years I was taught the virtues of tolerance; militancy in fighting for rights – but not bitterness. And as a social scientist I’ve always cultivated a coolness of temper, an attitude of objectivity when dealing with human sensitivities and irrationalities, which has always proved invaluable – never more so than in the Palestine negotiations. Success there was dependent upon maintaining complete objectivity.

Throughout the endless weeks of negotiations I was bolstered by an unfailing sense of optimism. Somehow, I knew we had to succeed. I am an incurable optimist, as a matter offact.»8

In these words he describes himself: the childhood heritage, the knowledge and experience acquired later in life – both factors going to make up the personality, the man who succeeded in getting both parties to lay down their arms. The outcome was a victory for the ideas of the United Nations, it is true, but as is nearly always the case, it was one individual’s efforts that made victory possible.

It is just over a year since Ralph Bunche completed his work of mediation. Today we are all confronted by even greater challenges than before. The future looks dark. But it is precisely in times like these that we must not lose heart; on the contrary, we must put our faith and all our strength in the fight against war.

Ralph Bunche, you have said yourself that you are an incurable optimist. You said that you were convinced that the mediation in Palestine would be successful.

You have a long day’s work ahead of you. May you succeed in bringing victory to the ideals of peace, the foundation upon which we must build the future of mankind.

* The ceremony on December 10, 1950, in the Auditorium of the University of Oslo was not only the usual one of commemorating the death of Alfred Nobel in 1896 and of presenting the Peace Prize for 1950, but also one of marking the fiftieth anniversary of the Nobel Foundation and fifty years of awarding the Nobel Prizes. In an opening address, Mr. Gustav Natvig Pedersen, vice-chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee and at this time president of the Norwegian Parliament paid tribute to the occasion and reviewed the history of the Peace Prize – touching on the Committees awarding it, the Nobel Institute and its directors, and the various categories of prizewinners. The address was followed by Mr. Jahn’s speech and his presentation of the 1950 prize to Mr. Bunche, who responded with a brief speech of acceptance. The translation of Mr. Jahn’s speech is based on the Norwegian text in Les Prix Nobel en 1950, which also carries a French translation.

1. Gunnar Myrdal (1898- ), Swedish sociologist and economist, conducted the study (1938-1942), which was sponsored by the Carnegie corporation and which was the basis for Myrdal’s book An American Dilemma (1944).

2. Bunche, «What America Means to Me», p. 123.

4. Count Folke Bernadotte (1895-1948), Swedish humanitarian, president of the Swedish Red Cross. For a biographical account, see Ralph Hewins, Count Folke Bernadotte: His Life and Work (London: Hutchinson, 1950).

5. Oscar II (1829-1907), king of Sweden (1872-1907). Sweden’s reigning monarch was Gustavus V (1858-1950), king of Sweden (1907-1950)

6. Bunche, «United Nations Intervention in Palestine», p. 13 of the address delivered at Colgate University, May 20, 1949, in Colgate Lectures in Human Relations, 1949.

8. «What America Means to Me», np. Cit., p. 125.