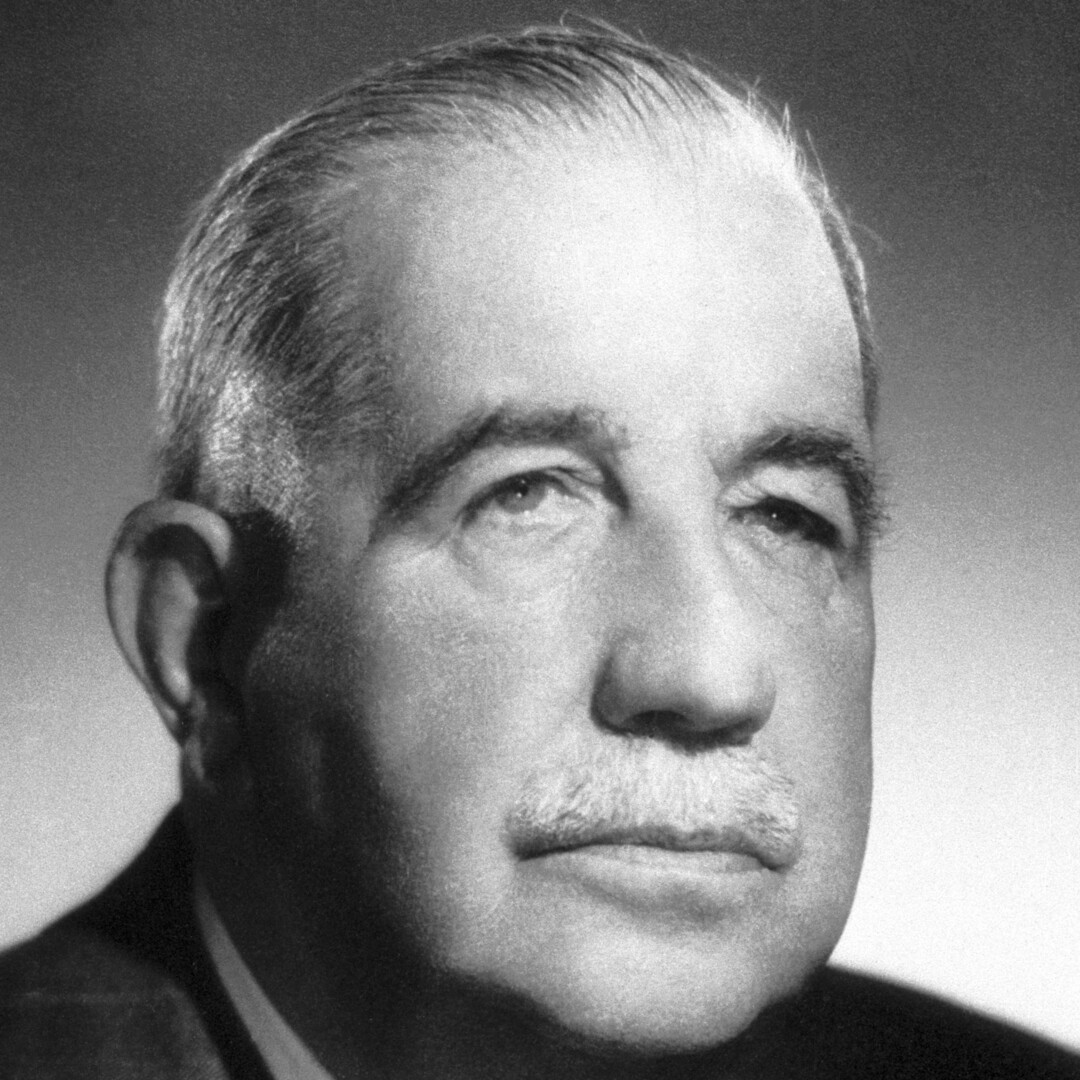

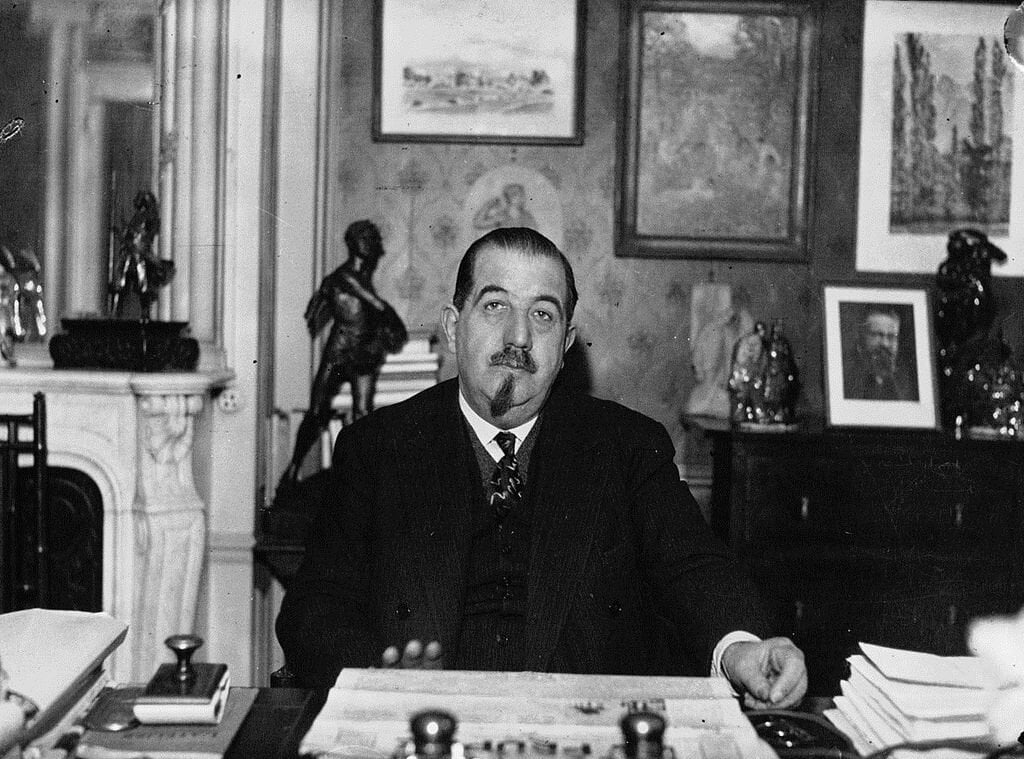

Dean of the French labor movement for forty-five years, Léon Jouhaux was born in Paris, heir to the radical beliefs of his grandfather who had fought in the Revolution of 1848 and of his father who had been a part of the Commune that had controlled Paris for a brief time in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War …

Léon Jouhaux – Speed read

Léon Jouhaux was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his lifelong struggle for the promotion of social justice and workers’ rights.

Full name: Léon Jouhaux

Born: 1 July 1879, Paris, France

Died: 28 April 1954, Paris, France

Date awarded: 5 November 1951

Social justice leads to peace

Léon Jouhaux grew up poor in a Paris suburb. His father, a match factory worker, became blind from over-exposure to white phosphorous. As a result, Léon had to go to work in the match industry to support his family. He became a labour union representative, and in 1909 he was elected secretary-general of the national labour organisation Conféderation Générale du Travail (CGT). In 1919 he helped to found the International Labour Organisation (ILO). During WWII, he was imprisoned by the Germans for his participation in the Resistance Movement. After 1945, he actively opposed communism, and worked to achieve German-French reconciliation and European unification. The award to Jouhaux was viewed as a tribute to a fellow partisan from the majority of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, who were members of the Norwegian Labour Party.

“He has devoted his life to the work of promoting brotherhood among men and nations, and to the fight against war.”

Gunnar Jahn, Presentation Speech, 10 December 1951.

“The action of the Norwegian Nobel Committee in awarding the peace prize to Jouhaux emphasizes the great importance that is being placed upon the fight against Communism.”

The US newspaper ‘Columbus Enquirer’, 10 November 1951

Jouhaux’ view of disarmament

In the 1920s Jouhaux participated in the unsuccessful disarmament negotiations in the League of Nations. He spoke out against large standing armies commanded by powerful general staffs, arguing instead for democratic people’s armies, patterned after the Swiss model, to be used for defence purposes only. According to Jouhaux, the arms industry should be made the property of the state and subjected to strict legislation and agreements. He also maintained that weapons manufacturers should be inspected by government authorities and regulated by supranational agencies. His dream of organising arms manufacturers across national borders is an early indication of his future support for the European Coal and Steel Community in the early 1950s.

“The Europe we are building will have more doors and windows than walls.”

Léon Jouhaux, Nobel Prize lecture, 11 December 1951.

A champion of European cooperation

In 1949 Leon Jouhaux became the first president of the European Movement. He was a keen supporter of the Schuman Plan, which paved the way for the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). The agreement for the ECSC was signed in 1951 by France, Germany, the Benelux states and Italy. The ECSC formed the basis of the EU. In his Nobel Prize lecture, Jouhaux underlined that a united Europe must show “that the democracies can bring about social justice through the rational organization of production without sacrificing the liberty and the dignity of the individual.”

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Léon Jouhaux – Nobel Lecture

English

Nobel Lecture*, December 11, 1951

(Translation)

Fifty Years of Trade-Union Activity in Behalf of Peace

It will certainly come as no surprise to you when I tell you that one of the most moving, as well as one of the happiest, moments of my life occurred on the evening of Monday, November 5, 1951. A reporter whose initiative I have already commended to the French Broadcasting System, eager to satisfy his professional conscience by extracting a sensational statement from me, came to inform me at a somewhat late hour that the Nobel Peace Prize Committee of the Norwegian Parliament had just bestowed on me one of the most renowned and flattering distinctions that this world can offer.

Perhaps he was disappointed by my reception and by the way in which I immediately identified myself with the working classes and their trade unions when I responded to the award of this prize, which reflects so much honour on its founder, on those whose mission it is to confer it, and on him who receives it. But I can assure you that not for the briefest instant did I believe that it was I alone who was the recipient of this great reward.

I have never ceased to do my utmost to be the faithful interpreter and devoted servant of the ideals of peace and justice upheld by out trade-union organizations, and at such a solemn moment it was natural for me to regard myself simply as their representative. I speak as their representative now as I review for you their constant efforts to hasten the advent of an era of peace for which all men long and in which, to borrow the words of Jean Jaurès1, “mankind, finally at peace with itself” will pursue its own destiny in joy and harmony.

My emotion was, nonetheless, great. Neither my friends nor my family, who should know me better than anyone else does, have ever doubted the strength of my nerves. They would be more likely to reproach me – and sometimes with less than kindly truculence -for a calmness that some of them call placidity. True enough, nature has endowed me with a fair measure of patience and composure, yet I should be lying if I told you that, having seen the reporter off on his way to make his deadline, I fell peacefully asleep. That evening, all that night, I waited in vain for a slumber that wouldn’t come.

And during those long hours I was assailed by many memories. I saw again the house where I was born, which disappeared in 1898 with the abattoir of Grenelle. I was not quite two years old when my parents left it and, after a brief stay in the country, made a home in Aubervilliers. This town so near Paris where I spent my youth was the Aubervilliers of the end of the last century. Being at that time more than half agricultural, it scarcely resembled the industrial city of today. It afforded us children wide-open spaces, covered with grain in the summer, and it gave us the clear waters of the Courneuve River flowing nearby where we spent many pleasant hours of bathing and swimming.

This almost rustic life made me a sturdy and stable man, and, despite the unpretentiousness of our family life and its hazards, I look back on those days with considerable pleasure.

However, it was at Aubervilliers that I felt for the first time the hard consequences of the struggle of the workers for improvement of their living conditions. These had a considerable influence on my future.

My father, a veteran of the Commune2, his convictions and his fighting spirit unbroken by the defeat of the workers in 1871, took an energetic and untiring part in the strikes which set the workmen of the match factory where he worked against the management of the company prior to its becoming nationalized. The courageous efforts of my mother, who resumed her job as a cook, were not enough to compensate us for the loss of my father’s wages, and it was during one of these strikes that I had to leave elementary school before I was twelve to work at the Central Melting House in Aubervilliers.

My parents, and especially my mother, encouraged by the director of the local school which I was attending, wanted in spite of everything to send me to a National School of Arts and Crafts so that I could later become an engineer. I was keen to study and had some natural mechanical ability, and so I entered the Colbert upper primary school. Less than a year later, because of a reversal of the family fortunes, I was forced to leave and go to work in the Michaux Soap Works. From this time on, except for one more attempt at schooling when I spent a year at the Diderot Vocational School, I was, at the age of fourteen, completely caught up in the hard life of the industrial worker.

When I was sixteen, I became a member of the trade union at the match works where I had rejoined my father. I did so without question. My father’s vigorous example and my own experience led me quite naturally to participate in the worker’s movement. I had suffered personally from the social order. My school work, my intellectual gifts, my eagerness to study, had all come to nothing. I had been brutally compelled to leave the upper primary school and even the vocational training school and to become a wage earner of the humblest order.

This day has been set aside for all countries to celebrate the anniversary of the adoption by the United Nations General Assembly of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights3. And with a passion fired by these memories of an adolescent deprived of the right to realize his full intellectual potential, I wish to express my own conviction that, thanks to the action of true trade unionists and sincere democrats, all the sacred and inalienable rights of man will henceforth be recognized without reservation and that man will be able to exercise these rights without hindrance.

The feeling of having been unjustly treated drove me to spend much time in the library of the Aubervilliers libertarian group, one of the few places where I could escape intellectually from my situation. Reading the books that I found there reinforced my feelings of rebellion against the established order and against social injustice.

I propose now to review the progress of trade-union activity for international peace. To this end I shall disregard all its other aspects, but first, in order to stress by a personal example its positive results with regard to the protection of the workers’ health, let me give you the reasons for the first strike in which I took part. I participated in this strike not simply as a member of the trade union but as its administrative secretary; in other words – to give you an exact idea of my functions and responsibilities in this humble office – I drafted the minutes of meetings of the trade-union council, of the general assemblies, and sometimes of delegations. I do not think that I owed this mark of confidence to my worth as a trade unionist; I owed it, more likely, to my having received a less sketchy education than that of my comrades: the great school reforms of the Third Republic had not yet been in existence ten years.

Instigated by the National Federation of Match Factory Workers4, itself adherent to the C.G.T. which had been established in 18955, this strike involved the whole trade corporation and aimed principally at prohibiting in the manufacturing process the use of white phosphorus, which constituted no small danger, particularly to the dental health of the personnel. The strike lasted over a month, but it led directly to the calling of the Bern Conference which prohibited the use of noxious substances6. This first success naturally could not fail to encourage me to persevere in trade-union action, which at the same time satisfied both my urge to work against iniquity and my youthful need for tangible achievements.

Another consequence of the same strike was the bringing into use of the “continuous” machine, as it was called, which increased production as it eased the drudgery of the workmen. This led me to understand that trade unionism, the instrument of working-class liberation and of social change could, and indeed should, be also an instrument of industrial progress. Nor did it take me long to see therein one of the most effective means for freeing the world of the always menacing specter of war.

Why should I not state openly, Ladies and Gentlemen, the fact that the first manifestation of the trade-union struggle for peace, and particularly the French trade-union struggle into which I threw myself with all the ardour of my youth, was antimilitaristic in thought and sometimes also in deed? Is not one of the greatest sins against the spirit that of knowingly concealing the truth? And would it not be ridiculous to reproach the trade-union movement with having confused cause and effect? Sociologists worthy of the name never make the mistake of reproaching primitive peoples for their belief that the sun moves round the earth. We too, through lack of knowledge and of sufficiently mature reflection, mistook the visible outward appearance of the phenomenon for the phenomenon itself. I would add that my memory of that period, perhaps because of the mirage which the passage of the years evokes, is that of a great enthusiasm, undoubtedly sparked more by irrational hope than by any constructive will; but that fervour makes me feel all the more bitter about the atmosphere of indifference, fatalism, and resignation that has persisted up to the present time on our continent, a continent which two wars seem to have ravaged morally as well as physically. An orator once exclaimed: “When war breaks out, its principal victims are always the people.” He was more right than he knew. Not only does war kill workers by the thousand, nay, by the million, destroy their homes, lay waste the fields which took them centuries of effort to cultivate, raze to the ground the factories they built with their own hands, and reduce for years the standard of living of the working masses, but it also gives man an increasingly acute feeling of his helplessness before the forces of violence, and consequently severely retards his progress toward an age of peace, justice, and well-being.

Oh yes! we were full of enthusiasm back in 1900. Nothing, no matter what it was, seemed impossible to us then, and we had every reason to believe it. We felt already that after Viktor Adler, Wilbur Wright was going to give us wings7.

On completion of my military service, I went back to the factory and to the trade union. From here on, however, I am going to take myself out of the story of the movement – not because our paths diverged, indeed they intermingle after 1909 – but because trade unionism, despite its close initial connections with libertarian individualism, is essentially and by definition a collective work.

A moment ago, I mentioned in passing the creation in 1895 of the Confédération générale du travail (C.G.T.). It replaced the National Federation of Trade Unions [Fédération des Syndicats et Groupes corporatifs ouvriers de France], which had been founded in 1886. Actually, unity of the workers under the C.G.T. was not completely achieved until 1902 when, at the Montpellier Congress, the Federation of Labour Exchanges (Fédération nationale des Bourses du travail) was incorporated in the C.G.T. as the Division of Labour Exchanges. However, during this period in which the unity of the working classes was being consolidated, the C.G.T., in its annual congresses, had already gone beyond questions of organization and corporate claims and as early as 1898 had taken its stand in favour of general disarmament:

“The Congress (the motion stated in a somewhat antiquated style) considering all peoples to be brothers and war to be mankind’s greatest calamity, [and]

Holding that armed peace leads all peoples to ruin through the increase in taxation required to meet the enormous expense of standing armies,

Declares that money spent on the perpetration of acts suitable only to barbarians and on the support of young, strong, and vigorous men for a period of years would be better used for work serving humanity, [and]

Expresses the wish [voeu] that general disarmament take place as soon as possible.”

In 1900 and in 1901, the C.G.T. progressed from theoretical declarations to practical considerations; it decided that “young workers about to undergo conscription should be put in touch with the secretaries of the Labour Exchanges of the towns in which they are to be garrisoned”, and agreed in principle to the setting up of a Serviceman’s Fund.

Today these declarations and decisions seem very mild. We must not forget, however, that they were accompanied by a significant antimilitaristic agitation which had found solid support in the impassioned propaganda for a retrial of the Dreyfus case8. This was opposed with equal vigour by militarists whose affinity with a discredited Council of War laid open the army and particularly its officers to fatal, if unfair, suspicion as far as democratic opinion was concerned.

All the C.G.T. congresses, which took place biennially after 1902, were deeply concerned with action in support of peace. At the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War9, the 1904 Congress, held at Bourges, declared: “At a time when two nations are at each other’s throats, re-enacting on a wider scale the slaughter of the past for the greater good of the ruling classes and exploiters who enslave the proletariat of the whole world, this Congress… censures the ignoble attitude of the governments of the two nations concerned, which, with the object of finding an outlet for the mounting discontent of the proletariat, appeal to chauvinistic passions and unhesitatingly organize the death and assassination of thousands of workers in order to safeguard their own privileged position.”

The international sky was increasingly overcast, and the attitude of the unions stiffened. The 1906 Congress approved “all programs of antimilitaristic propaganda”, and that of 1908 contemplated replying to a “declaration of war with a declaration of a revolutionary general strike”. The Congresses of 1910 and 1912 confirmed these resolutions and strongly protested against repression, but 1912 was the year of the Balkan War10 and, in view of the rivalries which began to make themselves felt and which threatened to spread the conflict even farther, a special conference held on the first of October decided to call a congress whose sole objective would be to combat the menace of war. The motion passed was a true indication of the confidence of the trade-union organizations in their growing strength. To stop the governments from being drawn any further down the slope to the yawning chasm of fire and blood, the Congress affirmed its resolution to take revolutionary action in the event of military mobilization.

We would gain a false impression of the importance and effectiveness of labour action if we confined ourselves to the motions passed at its congresses. The trade unions, far from being content with these declarations, established international liaisons and supported every policy based on pacification and understanding. Between 1900 and 1901 the C.G.T. and the English working classes together contributed to bringing about the Entente Cordiale11. To gain an idea of the value of this contribution, it is necessary only to reflect upon the tension which followed the Fashoda incident12 and to thumb through the collections of satirical publications of those days.

At the time of the Agadir incident13, on July 22, 1911, a delegation from the C.G.T. left for Berlin, and in the following month a trade-union delegation from Germany arrived in Paris. The French and the German proletariat were uniting their efforts to try to avert war.

These occasional international contacts were not, however, the only ones to be established between the various national trade-union organizations. Several international workers’ congresses were held after the abolition of the workers’ International. One met in Zurich in 1895 and one in London in 1896, bringing together delegates of the trade unions and representatives of socialist-minded political parties. In London, the French delegation included, among other trade unionists: Fernand Pelloutier, the Guérard brothers, and Keufer14. The results of this cooperation – or confusion, as the more critical historians would have it – were not outstanding, and the idea of a purely trade-union international organization first came up at the Congress of Scandinavian Trade Unions in Copenhagen in 1901, thanks to the direct contact among fraternal delegations. The proposal came from Legien15 who represented the General Committee of German Trade Unions. It was decided to request the various national organizations to attend the Congress of German Trade Unions at Stuttgart in 1902. The organizations of Germany, Great Britain, Austria, Belgium, Bohemia, Denmark, Spain, France, The Netherlands, Italy, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland responded to the appeal and approved the proposal to organize international trade-union congresses which would take place at more or less regular intervals. Their mandate remained limited, at first extending only to the compilation of common statistics, the exchange of information on legislation affecting labour, and eventually to solidarity in the event of important strikes. Nevertheless, the first international link had been forged, and it was later strengthened in Dublin in 1903 by the creation of an International Trade-Union Secretariat.

Without formally withdrawing from the Secretariat, our French C.G.T. suspended the payment of its contributions in 1904 after the Secretariat had refused to include the question of antimilitarism in the agenda for the Conference of Amsterdam. I would not go so far as to say that the French trade unions attached greater importance to the struggle for peace than the others did; but they certainly seemed to take it more to heart.

Relations were renewed following the C.G.T. Congress in Marseilles in 1908 and the Secretariat’s acquiescence to the demand that the calling of truly international congresses be included in the agenda of the next conference.

This, the fifth Conference, took place in Paris and included some spirited debates – quite spirited, in fact. Having become its secretary, I was the spokesman for the C.G.T. I recently referred to this meeting in an article, and I think I can do no better than to quote its opening words, for they pinpoint not only our own position but also that of the representative of the American Federation of Labour.

“I saw Gompers16 again (I wrote) on the evening of September 1, 1909. It was the second day of the International Conference of Trade-Union Secretariats. All day I had been asking for a true international congress, and I had had to ask with a certain amount of vehemence. At the end of the afternoon session, after we had won the majority over to the argument of the French C.G.T., Gompers, who represented the American labour unions belonging to the A.F. of L. [American Federation of Labour], came over to me to express his deep satisfaction !”

There were two more conferences, the first of which was in 1911 at Budapest where this time the A.F. of L. participated officially and the Industrial Workers of the World17 unofficially. The second was in Zurich in 1913. An attempt at an expanded conference, leading to the international congresses which we had in mind, was made on the latter occasion by appealing to the International Vocational Secretariats. The resolution adopted in Zurich recommended that the trade-union organizations of all countries study the possibility of setting up an International Federation of Labour, whose aim “would be to protect and extend the rights and interests of the wage earners of all countries and” – I emphasize this last part of the sentence – “to achieve international fraternity and solidarity”.

The trade-union movement was emerging from its infancy and beginning to be aware of the magnitude of its future. In Zurich it no longer thought of itself as the expression of a single social class; the international solidarity which it was trying to bring about was already something quite different from the solidarity of workers in time of strike – all that had been envisaged up to that time. The dramatic events which its development precipitated were soon to hasten its maturity.

Men of my generation will never forget the last days of July, 1914, least of all those who tried to build a dike against the onrushing sea of blood. After July 27 our C.G.T. never ceased trying to achieve the impossible. To leaders still adhering in spirit to the old motto of “Ultimate Right”, which kings used to engrave on their cannons, it opposed the common sense of the man in the street. “War”, it cried, “is no solution to the problems facing us; it is, and always will be, the most terrible of human-calamities. Let us do everything to avoid it.” On Friday, July 30, the C.G.T. cabled the supreme appeal to the International Secretariat, beseeching it to intervene by “exerting pressure on the governments”.

Alas! As we all know, these desperate efforts were in vain!

This disaster did not force us to abandon our ideal; on the contrary, from the very first months of the conflict, it led us to define precisely the conditions for its realization.

In fact, at the end of 1914, the A.F. of L. took the initiative of proposing to hold “an International Conference of National Trade-Union Organizations on the same day and in the same place that the Peace Congress would be held, in order to help restore good relations between proletariat organizations and to encourage participation with the Peace Congress in laying the foundations of a definitive and lasting peace”. Le Comité confédéral of the C.G.T. accepted this proposal and itself issued a manifesto to all the trade-union organizations. I believe that the major portion of this text has become less dated than all of its predecessors. It concludes by demanding: the suppression of the system of secret treaties; an absolute respect for nationalities; the immediate limitation of armaments on an international scale, a measure which should lead to total disarmament; and finally compulsory arbitration for the settlement of all conflicts between nations.

These ideas were soon well on their way. The milestones were to be the Conference of Leeds in 1916, that of London in September, 1917, and those of Stockholm and Bern in June and October of the same year.

At Leeds the idea of an international labour organization appeared in a trade-union text which also drew attention to the danger to the working classes inherent in the existence of international capitalist competition. In the report made on behalf of the C.G.T. we affirmed that the Peace Treaty should, in accordance with the spirit of workers’ organizations, lay the first foundations of the United States of Europe. In London there was strong support for the idea of the League of Nations itself, along with all its corollaries: general disarmament preceded by limitation of armaments, and compulsory arbitration, both of which the C.G.T. had advocated three years previously.

At Stockholm in June, 1917, the representatives of the trade unions in the Central European and Scandinavian countries declared their complete agreement with the decisions taken at Leeds and even expressed their congratulations to the union organizations of the Allied countries and most particularly to the C.G.T. Another International Conference of Trade Unions was called at Bern for the beginning of October, 1917, by the Association of Swiss Trade Unions. The national organizations of Germany, Austria, Bohemia, Bulgaria, Denmark, Hungary, The Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland were represented, and they confirmed the resolutions adopted at Leeds and London.

The Inter-Allied Labour and Socialist Conference which took place in London in February of 1918 was perhaps even more important. Our French organization delivered a memorandum there containing, certainly, many ideas that had already been voiced before, but in it we also demanded the creation of a supranational authority, the “formation of an international legislative assembly” and “the gradual development of an international legislation accepted by all and binding all in a clearly defined way”. We were ahead of our time, far ahead in fact, since thirty-three years later these proposals have still not been put into effect. The Conference requested that “at least one representative of socialism and of labour should sit with the official representatives at the official Peace Conference”. This request, which was reiterated by the C.G.T. on December 15, 1918, in more or less identical terms, was granted by two governments; in consequence, Gompers and I were attached to the delegations of the U.S.A. and France in the capacity of technical experts. We collaborated in bringing our efforts in behalf of the trade-union movement to bear on the elaboration of the Treaty, particularly insofar as Part XIII18 was concerned. The working classes were becoming more and more sharply aware of the complex causes of international malaise.

I shall quote two clauses from that part of the Treaty which gave birth to the International Labour Organization and to its permanent instrument the International Labor Office whose activities and tangible results I need not recall here. The two clauses of the Treaty read as follows :

“Whereas, The League of Nations has for its object the establishment of universal peace, and such a peace can be established only if it is based upon social justice;

And whereas, Conditions of labour exist involving such injustice, hardship, and privation to large numbers of people as to produce unrest so great that the peace and harmony of the world are imperilled; and an improvement of those conditions is urgently required…”

From 1918 on, trade unionists were to express from the platforms of their congresses the workers’ desire for peace through a rational organization of the world. The meetings of the International Labour Office and even the general Assemblies of the League of Nations, several of which were to have many sessions, were to excite universal interest in their proposals. The trade-union organizations nevertheless continued their autonomous activity. After the International Conference at Bern in February of 1919 and the Congress of Amsterdam in July of the same year, the International Trade-Union Secretariat was replaced by a true International Federation of Trade Unions19 which immediately acquired over twenty million members. One of its first acts was an appeal to International solidarity to alleviate the terrible misery prevailing within Austria; and the Austrian workers escaped famine, thanks to the many trainloads of supplies sent by various trade unions and cooperative societies. The second intervention of the F.S.I. was on behalf of the Hungarian trade unions, whose liberty was being threatened.

Some have forgotten – for forgetting is as blissful as ignorance – that the F.S.I. intervened with equal vigour on behalf of the Russian workers; its representatives, O’Grady, Wauters, and later Thomson, actually lived in Russia until 1923 in order to supervise the distribution of food and medicines sent by the Federation. Furthermore, it is not distorting history to say that it was largely through the efforts and propaganda of our International Federation that the government of the U.S.S.R. was recognized by the majority of the great powers.

However, the trade unionists did not confine themselves to mitigating the cruel consequences of war. They sought the means to establish a stable peace, emphasizing that it should be founded on a basis of worldwide economic and social stability. In fact, the majority of the proposals ultimately put before the League of Nations originated in the international congresses of the International Federation of Trade Unions and in the World Peace Congress which the latter convened at The Hague in 1922. We asked for the organization of exchanges, the circulation of manpower, the distribution of raw materials, and the prohibition of private manufacture of arms for international circulation.

It was at about this time that the League of Nations set up a Temporary Mixed Commission for the purpose of studying methods for dealing with international traffic in armaments, munitions, and war matériel20. The opinion of the workers now carried such weight that the Commission included three representatives of the workers from the Governing Body of the International Labour Office. A convention was drawn up on June 17, 1925, in which the principle of supervision, as opposed to that of simple propaganda, was recognized, thanks to the efforts of the labour members, of whom I was one. However, not all of our suggestions were followed; we had, for instance, requested internationalised supervision, the auditing of the books of business enterprises, proper measures designed to prevent influencing the press and the setting up of international cartels, together with the standardisation of national inspections.

It is curious to note – somewhat bitterly – that the principle of internationalised supervision always meets with strong opposition. Yesterday it came from the private manufacture of arms, today from armament itself I remain convinced, as do my comrades of the C.I.S.L 21, that we cannot talk seriously of general, or even of partial, disarmament, without accepting the need for effective international surveillance.

At the Economic Conference of 1927 I was again spokesman for the trade unions. The principal arguments in my statement of May 5, were as follows :

“On behalf of my comrades, representing the workers, I would like at this International Economic Conference to pay tribute to the recognition of the high ideals which the trade-union movement has always defended.

It is the opinion of the labour organizations that economic collaboration between peoples is a necessity. Immediately after the war during the armistice period – in February of 1919 – in examining the conditions necessary for peace and exploring the possible bases on which to found the League of Nations which was still on the drawing board, so to speak, the labour and socialist conferences, meeting simultaneously in Bern, emphasized the necessity of giving the League of Nations precisely that economic foundation which our chairman, Monsieur Theunis22, called for yesterday.

…In 1924, we declared that the organization of a definitive peace requires not only the institution of a law of peace but also that of an economy of peace… No true peace can be established… so long as quasi-military strategy is applied in economic relations. What is needed is a committee for economic cooperation.”

On May 23, the last day of the Conference, I voiced the sentiments of my friends when I said: “We have been bold in criticism, too timid in constructive action.”

Three years later, with the idea of concerted economic action in mind, the Conference sent a questionnaire to the member states of the League of Nations. The French government instructed the National Economic Council to work out the essentials of the French answer. I had been representing the C.G.T. on this council since its foundation in 1925, and I investigated the practical means of assuring the most satisfactory conditions for the distribution and optimum utilization of European raw materials among the various nations. Expressing the thoughts of my comrades, I suggested, among other means, the organization of an international information service on inventories, on production, and on the needs of the various countries for raw materials.

We also took an active part in 1931 on the Unemployment Committee of the Commission of Inquiry for European Union23, in 1933 at the Monetary and Economic Conference in London, and on the Comité des grands travaux internationaux, through which the International Labour Office and the League of Nations, taking up the proposals of the trade unions, sought to establish healthy collaboration among nations in the struggle against under-employment and toward the creation of new sources of wealth. But all these conferences, all these meetings, succeeded in doing nothing to rid the world of the prevailing economic crisis. The will to organize the world on a rational basis, or at least to modify its most apparent incongruities, had clearly not been strong enough to counteract the combined effects of inertia, egoism, and incomprehension.

Efforts to wrest weapons away from nations bending under the weight of so many instruments of death were equally futile. All the same, I cannot forget the first sessions of the Conference for the Limitation and Reduction of Armaments. Those early days of February, 1932, were days of hope for humanity. Millions confidently awaited the results of the proceedings of this conference, which was presided over by that veteran militant Laborite Henderson24, and we can claim, with justification, to have had a lot to do with the creation of this enthusiasm. The Socialist Workingmen’s International and the International Federation of Trade Unions, zealously vying with each other, had each collected thousands of petitions which the delegations presented to the conference. On February 6, after Vandervelde25 had spoken on behalf of the members of the Socialist Worker’s International, I conveyed to the conference the unqualified support of millions of trade unionists.

That day remains one of the highlights of my life. I was intensely aware that I was expressing not only the unanimous hope of the workers of an entire world, still bruised by the recent holocaust, but also their clear understanding of the real conditions necessary for disarmament. In their name, I assured the members of the conference of the complete readiness of the trade-union organizations to cooperate in making effective and sincere the procedures of national and international supervision, without which partial disarmament would be either illusory or inoperative.

The attempt to bring about disarmament was as fruitless as the efforts in the economic sphere, and a few years later, with empty stomachs as its excuse, Italian fascism launched itself upon Abyssinia. We trade unionists knew very well that peace was indivisible, and we had no doubt that the weakness of the League of Nations would render it powerless and herald a new period of massacre and destruction. We were insistent and even violent in our demands that the Covenant should be applied and that sanctions be put into effect. We were voices crying in the wilderness. The sanctions were not applied; war broke out in Ethiopia26; and it was followed fatally, logically, and inexorably by the intervention in Spain27, the reoccupation of the left bank of the Rhine28, the Anschluss29, the Munich agreements30, and the Second World War31.

I do not want to enlarge upon our opposition to this policy of weakness whereby the principle of collective security was abandoned. We know only too well what the lack of resolution on the part of the democracies has cost them.

Once more the earth was laid waste by war. Even so, we do not believe that action in the cause of peace is a Sisyphean labour; and that the deadly stone will forever keep on rolling back down to crush mankind. We will yet manage to lodge the stone firmly at the top of the hill.

As soon as the Fascists and Nazis had laid down their arms, the trade unionists began to rethink the problems of peace.

Toward the end of 1947, the C.G.T.-F.O32 revived the traditions and spirit of our old C.G.T., and in speeches, articles, and reports we again took up and specified the solutions which the C.G.T., along with the International Federation of Trade Unions, had offered to the world as a way to salvation.

We approved the Marshall Plan33 because it was a manifestation of international solidarity, because its benefits could be extended to any nation without discrimination, and because we could not see in it any expression of a policy of prestige or force of arms since it invested the beneficiary states with the right to use the credits as they saw fit.

We approved the propaganda in favour of European Unity and emphasized that we would regard such unification as the first step on the road to World Unity. In my capacity as a trade unionist, I was elected president of the European Movement in February of 1949, and in the following spring I opened the Westminster Economic Conference34 by expressing our common sentiment as follows:

“It is normal, it is logical, it is in conformity with the very spirit of history that the organized working class should have an active part in the construction of Europe. It has always proclaimed that it would not, could not, and had no wish to disassociate the struggle for its emancipation from the constant battle to maintain peace, because doing so would have set up barriers which international events would have swept away like piles of chaff.”

It is a matter of Europe’s consolidation, not of its isolation. This human mass, which has such a vast wealth of natural resources at its disposal and whose intellectual potential is the greatest on earth, is not willing to cut itself off from the rest of the world. It is ready to welcome all who wish to be associated with its efforts: “The Europe we are building will have more doors and windows than walls.”

In July, 1950, in an introduction to the reports on the Social Conference of the European Movement, I stressed again the importance of its objective of international peace and of social justice:

“We want to make Europe simply a peninsula of the vast Eurasian Continent, where for thousands of years war has been the only way to resolve conflicts between peoples. We want Europe to be a peaceable community united, despite and within its diversity, in a constant and ardent struggle against human misery and all the suffering and dangers that it engenders. We have no desire to make Europe into a larger, better entrenched, better armed fortress.”

We approved the Schuman Plan for a European Coal and Steel Community35. A few days after the declaration of May 9, 1950 – on May 31 to be exact – in commenting on the Ruhr Statute36 in a C.I.S.L. Conference journal, I wrote :

“The promoters of the can take as their objective… only the progressive unification of Europe. However, this unification cannot be an end in itself.

The final and essential goal, the only valid goal, is to extend the well-being of the worker, to give him a more equitable share of the products of collective work, to make Europe a social democracy, and to ensure the peace desired by men of every race and tongue by proving that the democracies can bring about social justice through the rational organization of production without sacrificing the liberty and the dignity of the individual.

… The pool should be only one stage in a process of continuous creation. The C.I.S.L. has decided to follow its development closely in order to be in a position to give it effective collaboration.”

We recommended the organization of a worldwide market for raw materials and in this connection recalled just what it is that we intend to defend in defending democracy :

“What are we all trying to save? What are we trying to safeguard? Civil liberties: specifically, the right of all citizens to hold their own opinions and to express them freely on the great questions of moral, philosophical, political, and economic import, and the right to form associations. But democracy is not, nor can it be, merely a theoretical respect for these rights. It must give every man effective opportunities to enjoy them, and it must do so under the kind of moral and material conditions that will encourage him to exercise such rights.

One who must be constantly preoccupied with his own subsistence cannot be an alert citizen.

I said recently in a short address to the Economic Council that economic justice is one of the factors in the moral health of nations. There is no economic order in inflationist policies and in underemployment.”

The C.I.S.L. commissioned me to put before the U.N. Assembly at Lake Success a draft resolution whose main paragraph read as follows: “The General Assembly… recommends to the participating nations that they seek above all the means of establishing international regulation of the distribution and cost of raw materials and that, to this end, they contribute to the creation of a common stabilization fund.”

We have constantly defended the two inseparable principles of collective security and general disarmament, effected through the reassessment and international supervision of military strength and of all categories of instruments of war.

A synthesis of our doctrine was attempted on the occasion of the C.I.S.L. Congress at Milan in July, 1951, in the report on the role of the trade-union movement in international crisis.

In this report we have fixed our objectives: first and above all, to spare humanity the colossal ordeal of a third world war.

In it we have stated our principles : to act within the framework and under the aegis of the United Nations Organization, to develop a spirit of community and a spirit of cooperation, and to return to collective economic disciplines.

Finally, we have set forth some of the forms our activity will take: the organization of the distribution of raw materials and the fixing of the prices of basic products; the solution of the housing problem; the fight against restrictive practices in production by national and international cartels; and above all the effective participation of the organized workers in the management of social and economic affairs in every country in the world. Since this Congress is the most recent of the many manifestations of the desire for peace on the part of the free trade unions, I believe I could give no better conclusion to this survey of fifty years of trade-union activity in behalf of the rational organization of the world and of peace – which are absolutely inseparable – than by giving the final lines of this report practically unaltered.

The free trade-union movement is called on to play an essential part in the fight against international crisis and for the advent of true peace. The scope of the task is enormous, matched only by its urgency. Our movement intends to devote its efforts to this task regardless of the cost. I might add that it was enormously encouraged by the recent interventions of the government delegates on the Third Committee of the present General Assembly of the United Nations. The Cuban delegate Mr. Ichaso, among others, showed that certain official circles had adopted the idea which we have been propagating for years and which we have already succeeded in putting into the Treaty of Versailles: the idea that economic disorder and misery are among the determinative causes of wars.

The decision of the Committee of the Norwegian Parliament, which, in awarding me the Nobel Peace Prize for 1951, has recognized and proclaimed the importance and the steadfastness of the pacifist efforts of the trade unionists, cannot but greatly assist the spread of these ideas and considerably extend their sphere of influence. It strengthens the common will of those who have conceived and submitted these ideas to the consideration of men, and of those who have been convinced by them, to work ceaselessly to develop a society free of injustice and violence.

We know well, alas, that men and their civilizations are mortal. We wish to leave to indifferent nature the responsibility of their demise and to free mankind at last from its remorse for having begotten Cain.

* The laureate delivered this lecture in the auditorium of the Nobel Institute. The translation is based on the French text in Les Prix Nobel en 1951.

1. Jean Léon Jaurès (1859-1914), prominent French Socialist politician, writer-editor, and pacifist.

2. The Commune of Paris (March-May, 1871) was set up at the end of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) by the Parisians who, refusing to accept Prussian peace terms, held the city, with the aid of the French National Guard, against the French provisional government at Versailles; the workers, who had protested the war from the beginning, had a large part in encouraging and implementing the revolt.

3. On December 10, 1948. See René Cassin, pp.383-411.

4. Fédération nationale des Ouvriers et Ouvrières des manufactures d’allumettes.

5. Confédération générale du travail [General Confederation of Labour] known as the C.G.T.; one of the leading French labour organizations, it included, before WWI, almost all of the organized workers in France. Although individually its worker members usually voted for Socialists, the C.G.T. kept itself free of any actual party affiliations until the 1940’s when the Communists gained control of the organization.

6. Conferences were held in Bern in 1905 and 1906; France was one of the countries that ratified the resulting convention against use of white (or yellow) phosphorus.

7. Viktor Adler (1852-1918), Austrian politician, leader of the Austrian Social Democratic Party. Wilbur Wright (1867-1912), American inventor (with his brother Orville) of the airplane.

8. See 1927 presentation speech, Vol. 2, p.30, fn.2.

10. Two brief Balkan Wars (1912-1913) involved Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro, Rumania, and Turkey in a struggle for Turkish territory.

11. An informal understanding between Great Britain and France (1904), settling then colonial differences.

12. A diplomatic crisis in Anglo-French relations (1898), involving rival claims in the upper Nile region, occurred when the French took the town of Fashoda in S. Sudan while the British were putting down a revolt in N. Sudan. A peaceful settlement was effected, with the French giving up their claims.

13. Franco-German relations were strained in 1911 when French troops intervened in a Moroccan uprising and the German warship Panther appeared at Agadir; mutual agreements resolved the crisis.

14. Fernand Pelloutier (1867-1901), secretary of the Fédération nationale des Bourses du travail and manager of the weekly journal L’Ouvrier des deux mondes. One of the Guérard brothers was at one time secretary of the C.G.T. Auguste Keufer (1851-1924), positivist leader of the French union reform movement; secretary of the Fédération du livre until 1920.

15. Karl Legien (1861-1920), chairman of the General Committee of the German Free Trade Unions.

16. Samuel Gompers (1850-1924), American labour leader; in 1881 helped to found the Federation of Organized Trades and Labour Unions, which became the American Federation of Labour (A.F. of L.) in 1886; president of A.F. of L. (1886-1924, except 1895).

17. The I.W.W. was a revolutionary industrial union founded in Chicago in 1905 which aimed to overthrow capitalism and to set up a trade-union state.

18. Part XIII of the Treaty of Versailles became the constitution of the International Labour Organization.

19. Fédération syndicale internationale, or F.S.I.; dissolved in 1945 ; succeeded by the World Federation of Trade Unions.

20. The Temporary Mixed Commission for the Reduction of Armaments, constituted in 1921, also studied other aspects of the armament problem.

21. Confédération internationale des syndicats libres, formed in 1949 to counter the World Federation of Trade Unions which had become Communist dominated.

22. Georges Theunis (1873-1966), Belgian statesman and twice prime minister.

23. The Commission of Inquiry for European Union was created in September, 1930, under the auspices of the League of Nations, with Aristide Briand its president. Its Unemployment Committee was authorized by the League Council early in 1931.

24. Arthur Henderson (1863-1935), recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for 1934. See Henderson, in Volume 2, for details on this conference.

25. ÉmiIe Vandervelde (1866-1938), Belgian Socialist leader and statesman; minister of state (1914-1918), minister of justice (1919), minister of foreign affairs (1925).

26. In 1935 between Ethiopia and Italy; Italian victory and annexation of Ethiopia followed in 1936.

27. In the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), Germany and Italy supported one side, Russia the other.

28. Germany violated the Treaty of Versailles (1919) and the Locarno Pact (1925) by reoccupying the Rhineland in 1936.

29. The union of Austria and Germany, which took place, in defiance of the 1919 peace treaties, when Germany annexed Austria in March, 1938.

30. The Munich Pact of September, 1938, signed by Great Britain, France, Germany, and Italy, allowed Germany to occupy the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia.

32. Force Ouvrière, a non-Communist labour federation officially known as C.G.T.- F.O., was formed in 1947 by a group (including Jouhaux) that seceded from the C.G.T. because of its Communist control.

33. The European Recovery Program, integrating U.S. aid to Europe (after WWII) with an organized program of recovery and cooperation in Europe itself, was proposed (1947) by George C. Marshall, U.S. secretary of state (1947-1949) and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for 1953.

34. The European Movement (for European unity) later in 1949 created the Council of Europe, whose objective is a more closely integrated European community. For an account of the Movement and its Westminster Economic Conference, see European Movement and the Council of Europe, with Forewords by Winston S. Churchill and Paul-Henri Spaak, published on behalf of The European Movement by Hutchinson, London, 1950.

35. A plan proposed on May 9, 1950, by Robert Schuman (1886-1963), French foreign minister (1948-1953), for a European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) whose members would pool their coal and steel, providing a unified market for them – this to be done and regulated under a supranational authority; the ECSC was established in 1952, with France, Italy, West Germany, Belgium, The Netherlands, and Luxembourg as members.

36. Adopted in December, 1948, at a conference held in London by the United States, Great Britain, France, and the three Benelux countries, it provided an authority under which West German coal, coke, and steel were apportioned between German domestic consumption and export.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Léon Jouhaux – Banquet speech

Léon Jouhaux – Conférence Nobel

Conférence Nobel, prononcé à Oslo le 11 décembre 1951

Cinquante ans d’action syndicale en faveur de la paix

Mesdames, Messieurs,

Je ne vous surprendrai certainement point en vous assurant qu’une des plus profondes émotions de ma vie, une des plus heureuses aussi, me fut causée le lundi soir 5 novembre 1951 par ce journaliste dont j’ai déjà évoqué l’initiative à la Radiodiffusion française et qui empressé, pour satisfaire sa conscience professionnelle, à m’arracher une sensationnelle déclaration, vint m’annoncer à une heure déjà tardive que le Comité du Storting Norvégien pour le Prix Nobel de la Paix venait de me décerner l’une des plus honorables et des plus flatteuses distinctions mondiales.

Je ne sais s’il a été déçu par mon accueil et par le rapport que je fis spontanément de ma personne à la classe ouvrière organisée dans les syndicats, quant à l’attribution de ce prix qui honore à la fois son fondateur, ceux qui ont la haute mission de le décerner, et celui qui le reçoit, mais je puis vous affirmer que pas un instant, aussi bref fut-il, je n’ai cru que c’était moi seul qui étais l’objet de cette haute récompense.

Je n’ai jamais cessé de m’efforcer d’être l’interprète fidèle et le serviteur dévoué de l’idéal de paix et de justice de nos organisations syndicales et en cet instant solennel, il était naturel que je m’estime toujours leur simple représentant. Comme je le serai lorsque j’évoquerai tout à l’heure devant vous la permanence de leur action pour l’avènement tant désiré par tous les peuples d’une ère pacifique au cours de laquelle, pour reprendre l’expression de Jean Jaurès, «l’humanité enfin réconciliée avec elle-même», poursuivra son destin dans la concorde et dans la joie.

Mon émotion n’en fut pas moins fort vive. Ni mes amis, ni ma famille mieux renseignée encore, n’ont jamais mis en doute la robustesse de mes nerfs. On m’aurait plutôt volontiers reproché – et parfois avec une certaine truculence pas toujours bienveillante–un calme que certains appelaient placidité. Et il est vrai que la nature m’a suffisamment doté de patience et de sangfroid. Mais je mentirais en vous déclarant que, la porte fermée sur le journaliste courant à son marbre, je me suis fort tranquillement endormi. Ce soir-là, cette nuit-là, j’ai vainement cherché un sommeil décidé à me fuir.

Et durant ces longues heures, des souvenirs en foule m’ont assailli.

Je revoyais ma maison natale disparue en 1898 avec l’abattoir de Grenelle. Je n’avais pas tout à fait deux ans lorsque mes parents la quittèrent pour s’installer, après un bref séjour en province, à Aubervilliers. Cette ville si proche de Paris où je passai ma jeunesse était l’Aubervilliers de la fin du dernier siècle. Encore plus qu’à moitié agricole, il ne ressemblait guère à la cité industrielle d’aujourd’hui. Il nous offrait, à nous autres enfants, de grands espaces libres couverts de blé en été, et la claire rivière de la Courneuve qui coulait à proximité nous donnait les plaisirs de la baignade et de la natation.

Cette vie quasi campagnarde fit de moi un homme robuste et équilibré et, malgré la modestie de notre vie de famille et ses aléas, je garde de cette période de ma vie une image assez agréable.

Cependant, c’est à Aubervilliers que je sentis pour la première fois peser sur moi les dures conséquences de la lutte des travailleurs pour l’amélioration de leurs conditions d’existence. Elles eurent même sur ma destinée une influence considérable.

Mon père, ancien combattant de la Commune, mais dont la défaite ouvrière de 1871 n’avait abattu ni les convictions ni l’ardeur combative, participa avec persévérance et énergie aux grèves qui dressèrent les ouvriers de la Manufacture d’allumettes où il travaillait contre la Compagnie fermière qui précéda la mise en régie. La vaillance de ma mère qui avait repris son métier de cuisinière ne pouvait pas compenser la suppression du salaire paternel et, à l’occasion d’une de ces grèves, je dus quitter l’école primaire avant ma douzième année pour entrer au Fondoir Central d’Aubervilliers.

Mes parents, et tout spécialement ma mère inspirée par le directeur de l’école communale que je fréquentais, voulaient néanmoins faire de moi un élève d’une Ecole Nationale des Arts et Métiers et plus tard un ingénieur. J’avais le goût de l’étude et des dispositions naturelles pour la mécanique et j’entrai à l’école primaire supérieure Colbert. Des revers familiaux m’obligèrent à la quitter moins d’un an après et j’allai travailler à la Savonnerie Michaux. Malgré une autre tentative scolaire qui me fit passer encore un an à l’Ecole professionnelle Diderot, c’est bien de cette époque, c’est bien à partir de ma quatorzième année que j’ai été mêlé intimement à la dure vie des travailleurs de l’industrie.

A seize ans, j’adhérai au Syndicat de la Manufacture d’allumettes où je venais d’entrer rejoindre mon père. Cette adhésion ne me coûta aucun débat de conscience. L’exemple viril de mon père et ma propre expérience me portaient tout naturellement à participer à l’action ouvrière. J’avais souffert personnellement de l’ordre social. Mon travail scolaire, mes dispositions intellectuelles, mon goût de l’étude n’avaient servi à rien; j’avais brutalement été rejeté de l’Ecole primaire supérieure, de l’Ecole professionnelle même et j’avais été contraint à n’être qu’un salarié d’une des plus humbles catégories.

En ce jour consacré à célébrer dans tous les pays l’anniversaire de l’adoption par l’Assemblée Générale des Nations Unies de la Déclaration universelle des Droits de l’Homme, je veux, avec une passion qu’avivent ces souvenirs de mon adolescence privée du droit d’atteindre son plein épanouissement intellectuel, exprimer ma certitude que grâce à l’action des véritables syndicalistes et des démocrates sincères, tous les droits inaliénables et sacrés de l’homme lui seront dorénavant reconnus sans nulle restriction et qu’il pourra les exercer sans entrave.

Le sentiment de l’épreuve injustement subie m’avait porté à fréquenter la bibliothèque du groupe libertaire d’Aubervilliers, un des rares endroits où je pouvais intellectuellement m’évader de ma condition et j’avais renforcé par la lecture des auteurs que j’y trouvais mes sentiments de révolte contre l’ordre établi et l’injustice sociale.

Mon propos est de retracer les progrès de l’action ouvrière syndicale pour la Paix internationale; je négligerai donc tous ses autres aspects, mais afin de souligner par un exemple personnel ses résultats positifs dans le domaine de la protection sanitaire des travailleurs, je donnerai les motifs de la première grève à laquelle j’ai participe, à laquelle j’ai participé d’ailleurs non seulement comme adhérent du syndicat, mais encore en qualité de Secrétaire administratif, c’est-à-dire pour donner de cette fonction et des responsabilités qui m’incombaient une idée exacte et somme toute assez humble, de rédacteur de procès-verbaux des réunions du conseil syndical, des Assemblées générales et parfois des délégations. Je ne crois pas que je devais cette marque de confiance à ma valeur syndicale, je la devais plus vraisemblablement à mon instruction un peu moins sommaire que celle de mes camarades: les grandes lois scolaires de la jème République n’avaient pas encore dix ans.

Décidée par la Fédération Nationale des Ouvriers et Ouvrières des Manufactures d’allumettes, adhérente elle-même à la C.G.T. qui venait de se constituer en 1895, cette grève intéressa l’ensemble de la corporation et elle avait pour objectif principal l’interdiction dans la fabrication, du phosphore blanc dont l’emploi était loin d’être sans danger particulièrement pour la dentition du personnel. Elle dura plus d’un mois, mais eut pour conséquence directe la réunion de la Conférence de Berne qui interdit l’emploi de la matière nocive. Ce premier succès ne pouvait évidemment que m’encourager à persévérer dans l’action syndicale qui répondait en même temps à mon désir de travailler contre l’iniquité et à mon besoin juvénile de réalisations tangibles.

Une autre conséquence de cette grève fut l’emploi de la machine dite «continue» qui accroissait la production tout en diminuant la peine des travailleurs. Elle me fit comprendre que le syndicalisme, instrument de libération ouvrière et de transformation sociale pouvait être et même devait être un facteur de progrès industriel. Je ne tardai pas à voir également en lui un des moyens les plus efficaces pour éloigner du monde le spectre toujours menaçant de la guerre.

Pourquoi cacherais-je, pourquoi tairais-je, Mesdames et Messieurs, que le premier aspect du combat syndical en faveur de la Paix, du combat syndical français tout particulièrement auquel je fus mêlé avec toute l’ardeur de ma jeunesse, fut l’antimilitarisme en paroles et quelquefois aussi en actes. Un des plus grands péchés contre l’esprit ne consiste-t-il point à cacher sciemment la vérité? Et ne serait-il pas ridicule de reprocher au Mouvement syndical d’avoir confondu la cause et l’effet? Les sociologues dignes de ce nom ne commettent jamais l’erreur de reprocher aux peuplades primitives leur croyance en un mouvement du soleil autour de la terre. Nous avons, nous aussi, faute de réflexions assez profondes et de connaissances assez étendues, pris l’aspect extérieur et apparent du phénomène pour le phénomène lui-même. Je me permettrai d’ajouter que je garde de cette époque peut-être à cause du mirage que la fuite des ans provoque le souvenir d’un grand enthousiasme fait de plus d’espérance irrationnelle que de volonté constructive sans doute, mais qui me fait trouver plus amère l’atmosphère d’indifférence, de fatalisme et de résignation qui s’étend à l’heure actuelle sur notre continent que deux guerres semblent avoir ravagé aussi moralement que matériellement. Un orateur s’est un jour écrié: «Quand la guerre passe, le peuple est toujours sa principale victime.» Il avait raison plus encore qu’il ne pensait. Non seulement la guerre tue des travailleurs par milliers, que dis-je, par millions, détruit leur logis, bouleverse les champs fécondés par leurs efforts séculaires, écrase des usines élevées de leurs mains et réduit pour des années le standard de vie des masses ouvrières, mais en donnant aux hommes un sentiment plus aigu de leur impuissance devant les forces de violence, elle retarde considérablement la marche de l’humanité vers l’âge de la justice, du bien-être et de la paix.

Oh oui! nous en avions de l’enthousiasme vers 1900. Rien ne nous semblait impossible dans aucun domaine. Et nous avions quelque raison de le croire. Nous sentions déjà que Wilbur Wright, après Victor Adler, allait nous donner des ailes.

A mon retour du service militaire, j’avais repris ma place à la Manufacture et au syndicat, mais je vais dorénavant m’effacer totalement derrière l’histoire du mouvement, non qu’elle soit différente de celle de ma vie – elles se confondent au contraire depuis 1909 – mais parce que le syndicalisme, malgré les rapports étroits qu’il eut à ses débuts avec l’individualisme libertaire est essentiellement et par définition même une ouvre collective.

J’ai évoqué tout à l’heure incidemment la création de la Confédération Générale du Travail en 1895. Elle remplaçait la Fédération Nationale des Syndicats qui s’était constitutée en 1886. En fait, l’unité ouvrière au sein de la C.G.T. ne fut vraiment réalisée qu’en 1902 lorsque la Fédération des Bourses du Travail en devint, au Congrès de Montpellier, la section des Bourses, mais durant cette période de gestation de l’union totale des travailleurs, la C.G.T., dans ses Congrès annuels, s’était déjà haussée au-dessus des questions d’organisation et des revendications corporatives. Elle s’était ainsi prononcée dès 1898 en faveur du désarmement général.

«Le Congrès, déclarait la motion en un style peut-être un peu vieilli,

«Considérant que les peuples sont frères et que la guerre est la plus grande calamité de l’humanité,

«Constatant que la paix année mène tous les peuples à la ruine par le surcroît d’impôts créés pour faire face aux énormes dépenses des armées permanentes;

«Affirme que l’argent dépensé pour des actes dignes des barbares et entretenir des hommes jeunes, forts, et vigoureux, pendant plusieurs années serait mieux employé à de grands travaux pouvant servir l’humanité;

«Forme le vou qu’un désarmement général ait lieu le plus vite possible.»

En 1900 et en 1901, elle passe de l’affirmation théorique aux considérations pratiques; elle décide que «les jeunes travailleurs qui ont à subir l’encasernement devront être mis en relation avec les secrétaires de Bourses du travail où ils seront en garnison» et vote le principe de la création d’une Caisse du Sou du Soldat.

Ces déclarations et ces décisions paraissent aujourd’hui fort anodines. Il faut se garder d’oublier qu’elles étaient accompagnées d’une agitation antimilitariste assez sérieuse qui avait trouvé un solide appui dans la propagande passionnée en faveur de la révision du procès Dreyfus à laquelle s’opposaient non moins passionnément les milieux militaires dont la solidarité avec un Conseil de guerre abusé rendait injustement, mais fatalement l’armée, particulièrement ses cadres, suspects à toute l’opinion démocratique.

Les Congrès Confédéraux qui ne sont plus que bisannuels à partir de 1902 s’intéressent tous à l’action en faveur de la Paix. Celui de 1904 tenu à Bourges au moment de la guerre russo-japonaise déclare:

«Au moment où pour le plus grand bien des dirigeants et des exploiteurs qui asservissent le prolétariat du monde entier, deux Nations s’entr’égorgent et rééditent avec plus d’ampleur les hécatombes des temps passés, le Congrès … flétrit l’attitude ignoble des gouvernements des deux nations intéressées, qui, dans le but de trouver un dérivatif aux réclamations ascendantes du prolétariat, font appel aux passions chauvines et ne craignent pas d’organiser le meurtre et l’assassinat de milliers de travailleurs pour conserver leur situation privilégiée.»

Le ciel international s’obscurcit de plus en plus et l’attitude des syndicats se raidit. Le Congrès de 1900 approuve «toute action de propagande antimilitariste» et celui de 1908 envisage de répondre à la «déclaration de guerre par une déclaration de grève générale révolutionnaire». Ceux de 1910 et de 1912 confirment les résolutions antérieures et s’élèvent surtout contre la répression, mais 1912 est l’année de la guerre des Balkans et devant les compétitions qui commençaient à se manifester et risquaient de généraliser le conflit, une Conférence extraordinaire tenue le 1er octobre décide un Congrès dont le seul objectif devait être la lutte contre la guerre menaçante. La motion votée témoigne bien de la confiance qu’avaient les organisations syndicales en leur force grandissante. Pour arrêter les Gouvernements sur la pente qui les entraîne au gouffre de flammes et de sang, le Congrès agite devant eux avec plus de violence le drapeau de l’action révolutionnaire substitué à la mobilisation.

On aurait d’ailleurs une idée fausse de l’importance et de l’efficacité de l’action ouvrière si l’on s’en tenait à ces motions de Congrès. Les organisations syndicales, loin de se contenter de ces déclarations, établissaient des liaisons internationales et appuyaient toute politique d’apaisement et d’accord. Entre 1900 et 1901, la C.G.T. et la classe ouvrière anglaise contribuent l’une et l’autre à l’établissement de l’entente cordiale et pour se rendre exactement compte de la valeur de cette contribution, il suffit de songer à la tension consécutive à l’incident de Fachoda et de feuilleter les collections de publications satiriques.

Au moment des incidents d’Agadir, le 22 juillet 1911, une délégation confédérale se rendait à Berlin et au mois d’août suivant, une délégation syndicale allemande venait à Paris. Le prolétariat français et le prolétariat allemand unissaient leurs efforts pour essayer de faire reculer la guerre.

Ces contacts internationaux circonstanciels n’étaient au demeurant pas les seuls établis entre les organisations syndicales nationales. Plusieurs Congrès ouvriers internationaux avaient eu lieu après la disparition de l’Internationale ouvrière. Ils s’étaient réunis à Zurich en 1895 et à Londres en 1896 et groupaient des représentants de partis politiques de tendance socialiste et des délégués des Syndicats. A Londres en particulier, la délégation française comprenait entre autres syndicalistes: Fernand Pelloutier, les frères Guérard et Keufer. Les résultats de cette coopération – les historiens plus sévères diront peut-être de cette confusion – ne furent pas des meilleurs et l’idée d’une organisation internationale purement syndicale vit jour au Congrès des Syndicats Scandinaves à Copenhague en 1901, grâce au contact direct des délégations fraternelles. La proposition émana de Legien, représentant de la Commission Générale des syndicats allemands. Il fut alors décidé de convoquer au Congrès des syndicats allemands de Stuttgart en 1902 les différents centres nationaux. Les organisations d’Allemagne, d’Angleterre, d’Autriche, de Belgique, de Bohême, du Danemark, d’Espagne, de France, de Hollande, d’Italie, de Norvège, de Suède et de Suisse répondirent à l’appel et approuvèrent l’organisation de Conférences syndicales internationales plus ou moins périodiques. Leur mandat restait limité, il ne s’agissait encore que d’établissement de statistiques communes, d’échanges de renseignements sur les législations du travail et éventuellement de solidarité en cas de grèves importantes. C’était néanmoins le premier lien international et il se renforça à Dublin en 1903 par la création du Secrétariat Syndical international.

Notre Confédération Générale du Travail française, sans se retirer formellement du Secrétariat, suspendit, dès 1904, le paiement de ses cotisations: le secrétariat ayant refusé d’inscrire à l’ordre du jour de la Conférence d’Amsterdam la question de l’antimilitarisme. Je n’irai pas jusqu’à dire que les syndicats français donnaient à la lutte pour la Paix plus d’importance que les autres; toutefois, ils y apportaient une passion plus apparente.

Les rapports furent repris à la suite du Congrès de la C.G.T. à Marseille en 1908 et d’un acquiescement du Secrétariat Syndical international à la demande de porter à l’ordre du jour de la prochaine conférence la réunion de véritables congrès internationaux.

Cette cinquième Conférence eut lieu à Paris. Elle vécut des débats animés, très animés même. Devenu Secrétaire de la C.G.T., je fue son porte-parole. J’ai récemment évoqué cette réunion dans un article et je crois ne pouvoir faire mieux que d’en citer le début, car non seulement, il situe notre position, mais encore celle du représentant de l’American Fédération of Labour.

«Je revois encore Gompers, écrivais-je, le soir du 1er septembre 1909. C’était le deuxième jour de la Conférence Internationale des Secrétariats syndicaux.

Toute la journée, j’avais demandé la réunion d’un véritable Congrès international et j’avais dû la demander avec une certains véhémence. En fin d’après-midi alors que nous avions moralement rallié la majorité à la thèse de la C.G.T. française, Gompers qui représentait les syndicats américains groupés dans l’A.F.L. vint me témoigner chaleureusement sa satisfaction!»

Il y eut encore deux Conférences, la première à Budapest en 1911, à laquelle participèrent officiellement cette fois l’A.F.L. et officieusement les Industrial Workers of the world, la seconde à Zurich en 1913. Un essai de conférence élargie, acheminement vers les Congrès internationaux que nous préconisions y fut tenté par l’appel aux Secrétariats professionnels internationaux. La résolution qui fut adoptée à Zurich recommandait aux centres syndicaux de tous les pays l’étude de la création d’une Fédération Internationale du Travail dont le but «serait la protection et l’extension des droits et intérêts des salariés de tous les pays et – j’insiste sur ce dernier membre de phrase – la réalisation de la fraternité et de la solidarité internationales».

Le mouvement syndical sortait de sa période infantile, il prenait conscience de l’ampleur de son destin. Il ne se considère plus à Zurich comme l’expression d’une seule classe la solidarité internationale qu’il veut réaliser est déjà toute autre chose que la solidarité ouvrière en cas de grève envisagée jusqu’alors. Les dramatiques événement dont la gestation se précipitait allait en accélérer la maturité.

Les hommes de ma génération n’oublieront jamais les journées de la fin de juillet 1914, ceux qui ont essayé de dresser une digue contre la marée de sang moins que les autres. A partir du 27 juillet, notre C.G.T. ne cessa de tenter l’impossible. Aux gouvernants qui gardaient encore au cour la vieille devise que les rois gravaient sur leurs canons: «ultime raison», elle opposa le bon sens populaire. «La guerre, cria-t-elle, n’est en aucune façon une solution aux problèmes posés, elle est et reste la plus effoyable des calamités humaines. Faisons tout pour l’éviter.» Le vendredi 30, elle envoya par télégramme le suprême appel au Secrétariat International, le conjurant d’intervenir par «pression sur gouvernements».

Hélas! Vous savez comme nous tous que ces efforts désespérés furent vains!

Ce désastre n’entraîna pas le renoncement à notre idéal: il nous fit préciser, dès les premiers mois du conflit les conditions de sa réalisation.

En effet, dès la fin de 1914, l’A.F.L. prit l’initiative de proposer la tenue «aux même lieu et jours où se tiendrait le Congrès pour la Paix d’une Conférence Internationale des Centrales syndicales nationales pour aider au rétablissement de bons rapports entre les prolétariats organisés et faire participer ceux-ci à rétablissement des bases d’une paix durable et définitive». Le Comité Confédéral de la C.G.T. accepta cette proposition et adressa lui-même un manifeste à toutes les Centrales syndicales. Je crois que la majeure partie de ce texte a bien moins vieilli que tous ceux qui l’ont précédé. Il conclut en demandant la suppression du régime des traites secrets, le respect absolu des nationalités, la limitation immédiate et internationale des armements, mesure qui doit précipiter leur suppression totale et enfin le recours à l’arbitrage obligatoire pour tous les conflits entre nations.

Ces idées vont faire leur chemin. Les étapes seront les Conférences de Leeds en 1916 et de Londres en septembre 1917, celles de Stockholm en juillet et de Berne en octobre de la même année.

A Leeds apparaît dans un texte syndical, avec la notion du danger couru par la classe ouvrière du fait de la concurrence capitaliste internationale l’idée d’une organisation internationale du travail. Dans le rapport établi au nom de la C.G.T., nous affirmions que le Traité de Paix devait, dans l’esprit des organisations ouvrières, poser les premières fondations des Etats-Unis d’Europe. A Londres, c’est l’idée même de la Société des Nations qui s’impose avec tous ses corollaires: le désarmement général précédé par la limitation des armements et l’arbitrage obligatoire que la C.G.T. avait lancée trois ans auparavant.

Réunis à Stockholm en juin 1917, les représentants des syndicats des pays centraux et Scandinaves se déclarent absolument d’accord avec les décisions prises à Leeds et adressent même des félicitations aux organisations syndicales des pays alliés et tout particulièrement à la C.G.T. Une autre Conférence syndicale internationale est convoquée à Berne pour le début d’octobre 1917 par l’Union Syndicale Suisse. Les Centrales nationales d’Allemagne, d’Autriche, de Bohême, de Bulgarie, du Danemark, de la Hongrie, de la Hollande, de la Norvège, de la Suède et de la Suisse y sont représentées et elles confirment les résolutions de Leeds et de Londres.