Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld was the youngest of four sons of Agnes (Almquist) Hammarskjöld and Hjalmar Hammarskjöld, prime minister of Sweden, member of the Hague Tribunal, governor of Uppland, chairman of the Board of the Nobel Foundation …

Dag Hammarskjöld – Photo gallery

1 (of 3) Dag Hammarskjöld at the General Assembly of the United Nations.

Photo: Dag Hammarskjöld. En minnesbok. Malmö 1961. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

2 (of 3) Dag Hammarskjöld (right). Photo taken in the 1950s.

Photo: SAS Scandinavian Airlines, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

3 (of 3) The funeral of Dag Hammarskjöld in Uppsala, 29 September 1961.

Photo: Dag Hammarskjöld. En minnesbok. Malmö 1961. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Dag Hammarskjöld – Speed read

Dag Hammarskjöld was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for turning the United Nations into an efficient and independent international organisation.

Full name: Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld

Born: 29 July 1905, Jönköping, Sweden

Died: 18 September 1961, Ndola, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia)

Date awarded: 23 October 1961

Diplomat and peace mediator

Dag Hammarskjöld, the UN’s second secretary-general, is the only Nobel Peace Prize laureate to have received the award posthumously. Hammarskjöld built up an effective, autonomous UN secretariat, adopting an independent stance in relation to the major powers. He is given much of the credit for the successful deployment of the UN military force in the Middle East after the Suez Crisis in 1956. He also ensured that the UN deployed a force with a mandate for armed intervention to the civil war in the Congo in the early 1960s. Hammarskjöld was killed in a plane crash in North Rhodesia in September 1961. It is still not known whether the plane was shot down or malfunctioned due to technical or pilot error.

| Suez Crisis International crisis arising after Great Britain, France and Israel attacked Egypt in autumn 1956. The aggressors were forced to withdraw due to pressure from the USA and Soviet Union. It marked the first time that the UN deployed peacekeeping forces. |

”It was he who launched the organization on its active career as the keeper of world peace, a task made infinitely difficult by the Cold War and by the fact that the UN was almost completely untested in operational crisis management and peace-keeping.”

Brian Urquhart, Hammarskjold, 1994.

”… it was the United Nations alone that worked to realize the establishment of the Republic of the Congo as an independent nation, and the man who above all others deserves the credit for this is Dag Hammarskjöld.”

Gunnar Jahn, Presentation speech, 10 December 1961.

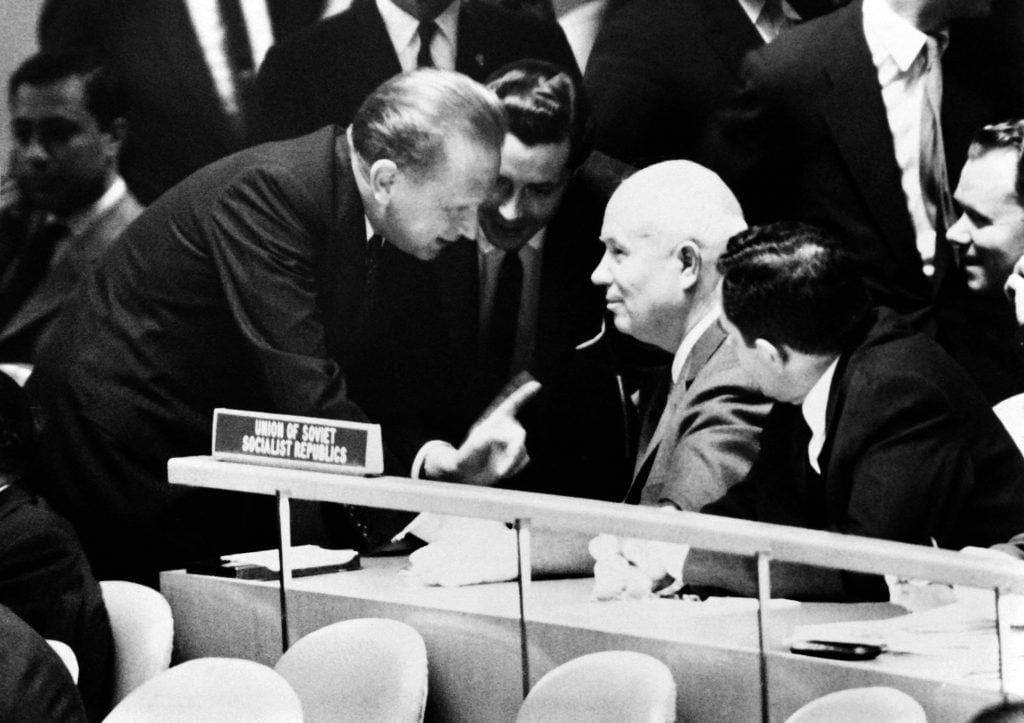

Hammarskjöld’s confrontation with the Soviet Union

Hammarskjöld’s call for the UN to intervene with armed force in the civil war in the Congo put him at odds with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. The Soviet leader demanded that the secretary-general resign, accusing him of being an “imperialist agent.” Hammarskjöld dismissed the criticism: “It is not the Soviet Union or, indeed, any other big powers who need the United Nations for their protection; it is all the others … I shall remain in my post during the term of my office as a servant of the Organization in the interests of all those other nations, as long as they wish me to do so.”

”A weak or nonexistent executive would mean that the United Nations would no longer be able to serve as an effective instrument for active protection of the interests of those many members who need such protection. The man holding the responsibility as chief executive should leave if he weakens the executive …”

Dag Hammarskjöld, Speech in the UN General Assembly, 3 October 1960.

Was Hammmarskjöld murdered?

In 2000, the book Drømmenes palass (‘Palace of Dreams’) by Bodil Katarina Nævdal (Norway) was released. The author presents material suggesting that mercenary soldiers from the apartheid regime in South Africa murdered Hammarskjöld in the plane wreckage. Nævdal also claims that the autopsy report may have been falsified. A UN report on Hammarskjöld’s death concluded that the secretary-general was killed in an accident. Nævdal’s book drew critical attention to the report. It is still unclear what actually occurred in the jungle outside Ndola just before midnight on 17 September 1961.

Was the secretary-general’s plane shot down?

In 2011, British newspaper The Guardian published new research on Dag Hammarskjöld’s death. Based on interviews with eye witnesses, Swedish Göran Björkdahl claimed that the UN plane was shot down by an unidentified fighter jet. In 1992 the same newspaper printed a letter from two of the secretary-general’s advisors with a theory that European mercenaries working for the Congolese breakaway province Katanga were responsible. Both Björkdahl and the advisors agreed that British colonial authorities tried to obscure the circumstances around the event.

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Dag Hammarskjöld – Acceptance Speech

Acceptance by Rolf Edberg*, Swedish Ambassador to Norway, on the occasion of the award of the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, December 10, 1961

It is with infinite sadness that I have received, at the request of the administrators of the estate of Dag Hammarskjöld, the prize for the year 1961 awarded posthumously to a friend and fellow countryman.

How thankful I should be if I could present to you what he himself would have thought and said, were he standing here today.

Surely he would have seen it as symbolic to be called to this stage – where so much human goodwill has been honoured – along with the South African advocate of nonviolent liberation: two men of different origin and with different starting points, but both striving toward the same goal.

My compatriot was much concerned with the awakening and fermenting continent which was to become his destiny. He once said that the next decade must belong to Africa or to the atom bomb. He firmly believed that the new countries have an important mission to fulfill in the community of nations. He therefore invested all his strength of will, and at the end more than that, to smooth their road toward the future.

Africa was to be the great test for the philosophy he wished to see brought to life through the United Nations.

Time and again he recurred to the indissoluble connection between peace and human rights. Tolerance, protection by law, equal political rights, and equal economic opportunities for all citizens – were prerequisites for a harmonious life within a nation. They also became requirements for such a life among nations.

He would remind us how man once organized himself in families, how families joined together in tribes and villages, and how tribes and villages developed into peoples and nations. But the nation could not be the end of such development. In the Charter of the United Nations he saw a guide to what he called an organized international community.

With an intensity that grew stronger each year, he stressed in his annual reports to the General Assembly that the United Nations had to be shaped into a dynamic instrument in the service of development. In his last report, in a tone of voice penetrating because of its very restraint, he confronted those member states which were clinging to “the time-honored philosophy of sovereign national states in armed competition, of which the most that may be expected is that they achieve a peaceful coexistence”1. This philosophy did not meet the needs of a world of ever increasing interdependence, where nations have at their disposal armaments of hitherto unknown destructive strength. The United Nations must open up ways to more developed forms of international cooperation.

He dated this report August 17 of this year. It now stands as a last testament.

He found the words of the Charter concerning equal rights for all nations, large and small, filled with life and significance. Above all, it was the small nations, and especially the developing countries, which needed the United Nations for their protection and their future. This was why he refused to step down and to throw the organization to the winds when one of the large nations demanded his resignation2.

It was impossible to witness that scene at the stormy session of last year’s General Assembly without recalling some words that he once wrote about his own father. “A man of firm convictions does not ask, and does not receive, understanding from those with whom he comes into conflict”3, he wrote about Hjalmar Hammarskjöld. “A mature man is his own judge. In the end, his only firm support is being faithful to his own convictions.”4 How aptly these words applied to himself when he rose unhesitatingly to defend the idea of a truly international body of civil servants or to uphold the principles of the Charter in the Congo operation!

If he felt any uneasiness, then it was because questions dealing with the peace and welfare of peoples were being treated in an overheated atmosphere. And an eyewitness, looking at him sitting there, deeply serious, with the fingers of his right hand against his cheek, as they always were when he was listening intently, might find himself asking this question: What does he represent, that slender man up there behind the green marble desk? A tradition of polished quiet diplomacy doomed to drown in the rising tide of new clamor? Or is he, with his visions of a world community, a herald of the future?

The latter is what we would like to believe. He himself had no doubt about the convincing force of his ideals. He expressed it thus in the last article that he wrote: “… set-backs in efforts to implement an ideal do not prove that the ideal is wrong …”.**

Such a conviction must be based on a determined philosophy of life. No one who met him could help noticing that he had a room of quiet within himself5. Probably no one was ever able really to reach into that room.

But perhaps we can think that he found something that was essential to himself in the last book that he was engaged in translating, the powerful work Ich und Du [I and Thou], in which the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber6 sets forth his belief that all real living is meeting. He himself believed that there were invisible bridges on which people could meet as human beings above the confines of ideologies, races, and nations.

And perhaps we may dare to see something significant in the obscurity and seeming futility of what happened on that African September night. Scattered about in the debris of the airplane were some books. Among them was Ich und Du, with some pages just translated into Swedish. Just before the plane took off on its nocturnal flight, he had left behind with a friend Thomas à Kempis’ Imitation of Christ7. Tucked in the pages was the oath of office of the Secretary-General:

“I, Dag Hammarskjöld, solemnly swear to exercise in all loyalty, discretion and conscience the functions entrusted to me as Secretary-General of the United Nations, to discharge these functions and regulate my conduct with the interest of the United Nations only in view …”.

Had he stood here today, he would, I believe, have had something to say about service as a self-evident duty.

My fellow countryman became a citizen of the world. He was regarded as such by the people from whom he came. But on that cool autumn day of falling leaves when he was brought back to the Uppsala of his youth, he was ours again, he was back home. Shyly he had guarded his inner world, but at that moment the distance disappeared and we felt that he came very close to us.

Therefore, I can speak on behalf of an entire people when I submit our respectful thanks for the honor that has been bestowed today upon our fellow citizen, the greatest honor a man can have. The Peace Prize awarded to Dag Hammarskjöld will constitute a fund which will bear his name and which will be used for a purpose that was close to his heart.

* At the award ceremony on December 10, 1961, after Mr. Lutuli had accepted his Peace Prize, Swedish Ambassador to Norway Rolf Edberg, representing the Hammarskjöld family, accepted the Peace Prize for 1961 awarded posthumously to Dag Hammarskjöld. The English translation of his speech is, with some editorial emendations, basically that appearing in Les Prix Nobel en 1961, which also carries the original Swedish text.

** Quote from Dag Hammarskjöld at the 15th Anniversary Dinner of the American Jewish Committee, 10 April 1957. Source: Foote, Wilder, ed., Servant of Peace: A Selection of the Speeches and Statements of Dag Hammarskjöld, Secretary-General of the United Nations 1953-1961, p. 128.

1. Introduction to the Annual Report 1960-1961 in Foote, Servant of Peace, p. 355.

2. The Soviet Union, criticizing Hammarskjöld’s actions in the Congo and charging him with bias, suggested in the UN General Assembly on September 23, 1960, that the office of secretary-general be replaced by a Committee of three, and on October 3, 1960, repeating the charges, called for Hammarskjöld’s resignation. For Hammarskjöld’s replies, including his refusal to resign, see Foote, op. cit., pp. 314-319.

3. From his inaugural address to the Swedish Academy, December 20, 1954, when he took the seat left vacant by his father’s death. Foote, op. cit., p. 64.

5. Probably a reference to the UN Meditation Room (located off the public lobby of the General Assembly Hall), which the laureate designed, and to the inscription on its black marble plaque, which he wrote: This Is A Room Devoted To Peace And Those Who Are Giving Their Lives For Peace. It Is A Room Of Quiet Where Only Thoughts Should Speak. Hammarskjöld also wrote the text of the leaflet given to visitors. Its first sentence reads: “We all have within us a center of stillness surrounded by silence.”

6. Martin Buber (1878-1965), Austrian-born philosopher, writer, and Judaic scholar; after exile from Germany (1938), a professor at Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

7. Thomas à Kempis (c. 1380-1471), German Augustinian canon and writer.

Dag Hammarskjöld – Documentary

Credit: ITN Archive/Reuters

Dag Hammarskjöld – Nominations

Dag Hammarskjöld – Other resources

Links to other sites

Dag Hammarskjöld – The UN years

On Dag Hammarskjöld from Dag Hammarskjöld Library at Uppsala University

‘Character Sketches: Dag Hammarskjöld’ from UN

Dag Hammarskjöld – Facts

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Gunnar Jahn*, Chairman of the Nobel Committee

The Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Parliament has awarded the Peace Prize for 1961 posthumously to Dag Hammarskjöld.

Dag Hammarskjöld was born in 1905, and prior to his appointment as Secretary-General to the Secretariat of the United Nations in 1953, he had been associated with the administration of his native Sweden ever since the completion of his education.

He had studied widely, and his knowledge ranged far beyond his chosen field. His special subject, however, was regarded as economics, in which he took his doctor’s degree in 1934, with a thesis entitled “Konjunkturspridningen.”1 He had by then already obtained degrees in philology and in law. In 1936 he entered the Swedish Ministry of Finance, and from 1941 to 1948, he was chairman of the Board of the Swedish Riksbank. In 1945 he became government adviser on trade policy and financial policy and in 1947 joined the Swedish Foreign Office. In 1951 he was appointed a consultative cabinet minister. But as he himself pointed out, he was committed to no particular party, and his cabinet appointment was a professional rather than a political one. In addition to leading various Swedish financial delegations in negotiations with other countries – primarily in connection with trade agreements – he also represented Sweden in UNISCAN2 negotiations and was for a time vice-chairman of OEEC.3

A brief recapitulation of this kind tells us little about Dag Hammarskjöld the man; nor does his well-merited reputation as a person of outstanding intellectual ability shed much light on his personality. So many men receive this tribute. Those of us who knew him before he became the Secretary General were also impressed by this young man’s wide knowledge and indefatigability, as well as by his quiet and unassuming approach to his administrative duties in the service of his country.

In 1953 he assumed his post as Secretary-General in the United Nations Secretariat. He had already come into contact with the United Nations as a member and vice-chairman of the Swedish delegation to the General Assembly in 1951 and as chairman of the delegation in 1952. As Secretary-General he succeeded Mr. Trygve Lie,4 who had not only built up the United Nations administration and participated in planning its new building, but had also given the post of secretary-general a more important and independent position within the United Nations than had probably been originally envisaged. In other words, he took over an office which had already been given form and an administrative apparatus which had acquired a certain amount of tradition.

There is no doubt that in accepting this high office Dag Hammarskjöld fully realized that the years ahead would not prove easy. He was all too familiar with the difficulties Trygve Lie had encountered to have any illusions on that score. Fully aware of the magnitude and complexity of his task, he devoted himself to it completely, exerting all his determination and strength in carrying it out. In a private letter written in 1953 he says: “To know that the goal is so significant that everything else must be set aside gives a great sense of liberation and makes one indifferent to anything that may happen to oneself.”

It has often been said that from the very first he wished to play the role of adviser rather than that of politician, or we might say that he preferred to be the one carrying out what others had decided rather than the one who made the decision.

As far as I can judge, this appraisal is not correct. From the beginning, back in 1953, when he outlined the role and activities of the Secretariat and the secretary-general, he laid down that, while it is clearly the duty of the Secretariat and of the Secretary-General to obtain complete and objective information on the aims and problems of the various member nations, the secretary-general must personally form an opinion; he must base it on the rules of the UN Charter and must never for a moment betray those rules, even if this means being at variance with members of the UN.

From the very first he placed great importance on the solution of disputes through the medium of private discussion between representatives of the individual countries, pursuing what has come to be known as the “method of quiet diplomacy.” There is, of course, nothing new in this, as informal meetings of this kind have always been and will always be an important part of the work necessary to achieve agreement between conflicting views.

Outwardly it may have looked as if he became more and more active as time went on, but this, I believe, can be ascribed more to the course of events than to any change in his views. In every situation with which he was faced he had one goal in mind: to serve the ideas sponsored by the United Nations. He called himself an international civil servant, with the emphasis on the word “international.”5 As such he had only one master, and that was the United Nations.

There can be little doubt that Dag Hammarskjöld achieved a great deal through the informal meetings he took part in, and that in these he demonstrated strong personal initiative; yet his personal contribution was best known to the general public in cases where attempts to reach agreement between members in the United Nations had failed, or where the instructions he had received were not sufficiently clear, and he was compelled personally to point the way, as we shall see. It is impossible to mention in detail the many areas in which he intervened and on which he left his mark during the time he was Secretary-General.

The first and most important disputes which fell to his lot to settle arose in the Middle East. The first of these was the conflict between Israel and the Arab States in 1955. As the representative of the UN, he succeeded in easing the tension by negotiating an agreement between each of the parties involved and the UN, setting up demarcation lines and establishing UN observation posts. Personally he did not believe that the relaxation of tension would prove permanent, and he was right in his surmise.

In the following year, in September of 1956, the conflict that arose between Great Britain, France, and Egypt, after Egypt had nationalized the Suez Canal, was submitted to the Security Council. In October, 1956, Dag Hammarskjöld tried to find a solution to this dispute through private negotiations conducted by himself, and it looked as if these would lead to a satisfactory result. But at the end of October, 1956, Israel attacked Egypt, and on October 30 the Security Council was called together to deal with the situation that had arisen. This meeting, however, proved abortive when France and Great Britain exercised their veto right to obstruct a resolution calling on Israel to withdraw her troops. On the next day, October 31, France and Great Britain launched their attack on Egypt. At the meeting of the Security Council on October 31, Hammarskjöld was the first person to speak. In a forthright speech he hinted that he would resign unless all member states honored their pledge to abide by all clauses of the Charter.

On October 31 the General Assembly was then convoked, and on November 1 passed a resolution calling on the parties concerned to terminate hostilities immediately and requesting the Secretary-General to keep a close watch on the course of events and to report on the way in which the resolution was being implemented. In reality the Secretary-General was thus vested with far-reaching powers. On November 3 Hammarskjöld was already able to announce that France and Great Britain were willing to suspend hostilities, provided that Israel and Egypt were prepared to accept the establishment of a UN force to ensure and supervise the suspension of hostilities and subsequently to prevent the violation of the Egyptian-Israeli border. The result was that the war was brought to an end, a demarcation line was fixed, and a UN force was established to guard it.

He also made a major contribution to the solution of a crisis between Lebanon, Jordan, and the Arab States in 1958. In this, both the United States and Great Britain were involved.

During these crises, all his qualities were given full scope, particularly his ability to negotiate and to act swiftly and firmly; and to Dag Hammarskjöld must go the principal credit for the fact that all these crises were resolved in the spirit of the United Nations. A state of peace was established in this area.6 This was a triumph for the ideal of peace of which the UN is an expression, and in addition undoubtedly greatly strengthened the position of the Secretary-General.

The concept of peace contained in the UN Charter was always to remain Dag Hammarskjöld’s guiding principle in tackling such problems as that presented by the liberation of the Congo on June 30, 1960.

There is no time to deal here with all the problems confronting the United Nations in connection with the termination of colonial rule. I must restrict myself to the role which the United Nations was to play in the Congo. When the Congo achieved its independence on June 30, 1960, it was constituted as a unified state. Kasavubu7 was elected president and Lumumba8 was made prime minister. Lumumba had always supported the idea of a unified Congo.

The new government was faced with a difficult situation: the administration, which had been in Belgian hands, had broken down; the army had mutinied; a large proportion of the white population had fled; Belgian troops had intervened – in part to protect the white inhabitants; and on July 1, the province of Katanga declared itself an independent state.

All these factors – the collapse of the administration, the mutiny of the armed forces, and finally Katanga’s secession from the rest of the Congo form the background for the request made to the UN by Kasavubu and Lumumba on July 1 for civil assistance and on July 12 for military aid. In a cable dispatched on July 13, Lumumba emphasized that UN military assistance was needed to protect the Congo against an attack by Belgian troops.

Hammarskjöld was in a position to grant the Congo’s request for civil aid without referring the case to the Security Council; military aid, however, could be given only by decision of the Security Council, which he summoned on July 13.

This meeting is highly important, for it marks a turning point in the history of the UN. It was the first time that the UN used armed force to intervene actively in the solution of a problem involving the termination of colonial rule. In the resolution unanimously adopted by the Security Council, Belgium was ordered to withdraw her troops from Congo territory, and the Secretary-General was authorized in consultation with the Congo government to provide whatever military aid proved necessary until such time as the country’s own forces were, in the opinion of the Congo government, in a position to carry out their functions.

The military aid made available to the Congo consisted of contingents from African nations and from neutral Sweden and Ireland. No troops from the Eastern bloc or from the old colonial powers were included. The UN force was to function as a noncombatant peace force; there was to be no intervention in disputes involving matters of internal policy, and arms were to be used only in self-defense.

This form of military aid did not meet the expectations of the Congo government, which had clearly envisaged the expulsion of Belgian troops by UN forces; whereas the UN’s action was taken on the assumption that Belgium would comply with the order of the Security Council and withdraw her troops from the Congo.

This Belgium failed to do, despite the fact that a note of July 14 addressed to the Congo government announced that Belgian troops would be withdrawn to two bases in Katanga as soon as UN forces had succeeded in establishing law and order.

Thus, during these first few days, UN intervention had not brought about the result Lumumba had anticipated. The Belgian troops remained in their bases in Katanga, and fresh Belgian troops were dispatched to the Congo.

As a consequence, during the period from July 14 to July 20, 1960, Lumumba made some highly unexpected moves. First of all, as early as July 14 he sent a cable to Khrushchev,9 announcing the possibility of asking for Russian aid if the Western powers continued their aggression against the Congo. On July 15 he had already received an encouraging reply from Khrushchev.

With that, the Congo crisis became a factor in the East-West conflict, rendering the position of Hammarskjöld and the UN in the Congo immensely difficult.

As the days and months went by, their position became no easier. All conceivable obstacles to the success of the UN’s Congo venture seemed to pile up: disagreement among the Congolese themselves on the question of unified state or confederation, the support Katanga received from Belgium, Soviet aid to Lumumba, the dissolution of the central government, the military rule under Mobutu, the murder of Lumumba, increasingly violent Russian attacks on Hammarskjöld and UN action. A complete account of all that occurred cannot be given here; but an examination of the available documents covering this period will establish that it was the United Nations alone that worked to realize the establishment of the Republic of the Congo as an independent nation, and that the man who above all others deserves the credit for this is Dag Hammarskjöld.

Time and again, in the Security Council and in the meetings of the General Assembly, he fought in defense of his policy and carried the day. He insisted throughout that all aid to the Congo civil as well as military – must be made available through the medium of the UN. No vested interests representing any of the power blocs must be allowed to exert their influence. Is it then surprising that he was the object of attack, at times from the West but most often and most violently from the Soviet Union, whose charges took the form of an assault on the very idea of the United Nations Organization as a separate power? In the calm and dignified answer which Dag Hammarskjöld made to the Soviet leaders, he said that he would remain at his post as long as this was necessary to defend and strengthen the authority of the United Nations. And he added: It is not Soviet Russia or any of the great powers that need the vigilance and protection of the UN; it is all the others.10

But he was not destined to live long enough to pursue his policy to its conclusion.

We all know that he perished on his way to a meeting which he hoped would bring an end to the fighting in the Congo between Katanga troops and UN forces, which had just broken out during the attempt to implement the UN resolution of February 21, 1961. This resolution called on UN military forces to take immediate steps to prevent a civil war in the Congo, and to use force only as a last resort. The UN was furthermore enjoined to ensure that all Belgian and other foreign military, political, and other advisers not under UN command should be withdrawn immediately.

Hammarskjöld left for the Congo on September 12, at the invitation of the Congolese government, to discuss the range and details of the UN’s program of aid to the Congo. When Dag Hammarskjöld left New York, he knew that the situation in Katanga was difficult, but it was not until he received Dr. Linner’s report on September 14 that he learned that Katanga forces and UN troops were fighting one another.11

Attempts to conclude a truce during the first few days of his visit proved unsuccessful; so Dag Hammarskjöld decided to establish personal contact with the President of Katanga, Tshombe;12 his purpose, as he explained in a message to Tshombe, was to find the means of settling the immediate conflict in a peaceful manner and thus open the way to a solution of the Katanga problem within the framework of the Congolese state.

The meeting never took place. Dag Hammarskjöld’s plane crashed on September 18 on its way to Tshombe. He and all the others aboard perished.

Then – and not till then – criticism of Hammarskjöld and UN policy in the Congo was silenced, but during the period from September 13 to 18, operations in the province of Katanga were severely criticized, this time in Western quarters, with the strongest assault coming from certain English Conservative newspapers.

Dag Hammarskjöld was exposed to criticism and violent, unrestrained attacks, but he never departed from the path he had chosen from the very first: the path that was to result in the UN’s developing into an effective and constructive international organization, capable of giving life to the principles and aims expressed in the UN Charter, administered by a strong Secretariat served by men who both felt and acted internationally. The goal he always strove to attain was to make the UN Charter the one by which all countries regulated themselves.

Today this goal may seem remote; as we know, it is remote. Dag Hammarskjöld fully realized this, and in a speech in Chicago in 1960 he said:

“Working at the edge of the development of human society is to work on the brink of the unknown. Much of what is done will one day prove to have been of little avail. That is no excuse for the failure to act in accordance with our best understanding, in recognition of its limits but with faith in the ultimate result of the creative evolution in which it is our privilege to cooperate.”13

His driving force was his belief that goodwill among men and nations would one day create conditions in which peace would prevail in the world.

The Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Parliament has today awarded him the Peace Prize for 1961 posthumously in gratitude for all he did, for what he achieved, for what he fought for: to create peace and goodwill among nations and men.

Let us stand in tribute to the memory of Dag Hammarskjöld.

* Mr. Jahn delivered this speech on December 10, 1961, in the auditorium of the University of Oslo, following his presentation of the Peace Prize for 1960 to Mr. Lutuli. At its conclusion he presented the Peace Prize for 1961 to Swedish Ambassador Rolf Edberg as representative of the Hammarskjöld family, five of whose members were present. The English translation of Mr. Jahn’s speech is, with certain editorial changes made after collation with the Norwegian text, that published in Les Prix Nobel en 1961, which also contains the Norwegian text.

1. Translated in Richard L. Miller, Dag Hammarskjöld and Crisis Diplomacy (p. 15), as “Expansion of Market Trends”.

2. UNISCAN (United Kingdom-Scandinavia) was a free trade project of the countries concerned, promoted in the early 1950s

3. OEEC (Organization for European Economic Cooperation), established in 1948.

4. Trygve Lie (1896-1968), Norwegian lawyer and statesman; chief representative of the Norwegian delegation at the organizing conference of the UN (1945); chairman of the commission that drafted the Charter; first UN Secretary-General (1946-1953).

5. See, for example, Hammarskjöld’s lecture, “International Civil Servant in Law and in Fact” delivered at Oxford University, May 30, 1961, in Foote, Servant of Peace, pp. 329-349.

6. For details of this and other conflicts mentioned, see Miller, Dag Hammarskjöld and Crisis Diplomacy.

7. Joseph Kasavubu (1917?-1969), African political leader who favored a Congolese federation rather than a strong central government.

8. Patrice Emergy Lumumba (1925-1961), African political leader who supported strong central government, was out of office two months later and eventually imprisoned in Katanga; killed there in 1961 by parties still unknown, he was considered a martyr by his followers.

9. Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (1894-1971), Russian premier (1958-1964).

10. Joseph Desire Mobutu (1930- ), commander of the Congolese army and “front man of the military regime (September, 1960-February, 1961) set up after the crisis precipitated by Lumumba; became president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1965.

11. After landing in Leopoldville and being ceremoniously welcomed by Congolese dignitaries, the laureate went to the home of Sture Linner, head of the UN mission in the Congo, who gave him his first news of the fighting that had begun during his flight to Africa.

12. Moise (Kependa) Tshombe (1919-1969), African political leader whose Opposition to strong central government resulted in Katanga’s secession from the Democratic Republic of the Congo; signed a cease-fire between Katanga and UN troops a few days after the plane crash, dedicating it to Hammarskjöld. Under UN pressure, Katanga was reintegrated with the Republic in 1963, and Tshombe became premier of the Republic (1964-1965).

13. These sentences conclude “The Development of a Constitutional Framework for International Cooperation”, a speech delivered at the dedication ceremonies of the new buildings of the University of Chicago Law School, May 1, 1960.

The Nobel Peace Prize 1961

Dag Hammarskjöld – Biographical

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld (July 29, 1905-September 18, 1961) was the youngest of four sons of Agnes (Almquist) Hammarskjöld and Hjalmar Hammarskjöld, prime minister of Sweden, member of the Hague Tribunal, governor of Uppland, chairman of the Board of the Nobel Foundation. In a brief piece written for a radio program in 1953, Dag Hammarskjöld spoke of the influence of his parents: “From generations of soldiers and government officials on my father’s side I inherited a belief that no life was more satisfactory than one of selfless service to your country – or humanity. This service required a sacrifice of all personal interests, but likewise the courage to stand up unflinchingly for your convictions. From scholars and clergymen on my mother’s side, I inherited a belief that, in the very radical sense of the Gospels, all men were equals as children of God, and should be met and treated by us as our masters in God.”1

Dag Hammarskjöld was, by common consent, the outstanding student of his day at Uppsala University where he took his degree in 1925 in the humanities, with emphasis on linguistics, literature, and history. During these years he laid the basis for his command of English, French, and German and for his stylistic mastery of his native language in which he developed something of the artist’s touch. He was capable of understanding the poetry of the German Hermann Hesse and of the American Emily Dickinson; of taking delight in painting, especially in the work of the French Impressionists; of discoursing on music, particularly on the compositions of Beethoven; and in later years, of participating in sophisticated dialogue on Christian theology. In athletics he was a competent performer in gymnastics, a strong skier, a mountaineer who served for some years as the president of the Swedish Alpinist club. In short, Hammarskjöld was a Renaissance man.

His main intellectual and professional interest for some years, however, was political economy. He took a second degree at Uppsala in economics, in 1928, a law degree in 1930, and a doctoral degree in economics in 1934. For one year, 1933, Hammarskjöld taught economics at the University of Stockholm. But both his own desire and his heritage led him to enter public service to which he devoted thirty-one years in Swedish financial affairs, Swedish foreign relations, and global international affairs. His success in his first position, that of secretary from 1930 to 1934 to a governmental commission on unemployment, brought him to the attention of the directors of the Bank of Sweden who made him the Bank’s secretary in 1935. From 1936 to 1945, he held the post of undersecretary in the Ministry of Finance. From 1941 to 1948, thus overlapping the undersecretaryship by four years, he was placed at the head of the Bank of Sweden, the most influential financial structure in the country.

Hammarskjöld has been credited with having coined the term “planned economy”. Along with his eldest brother, Bo, who was then undersecretary in the Ministry of Social Welfare, he drafted the legislation which opened the way to the creation of the present, so-called “welfare state. ” In the latter part of this period, he drew attention as an international financial negotiator for his part in the discussions with Great Britain on the postwar economic reconstruction of Europe, in his reshaping of the twelve-year-old United States-Swedish trade agreement, in his participation in the talks which organized the Marshall Plan, and in his leadership on the Executive Committee of the Organization for European Economic Cooperation.

Hammarskjöld’s connection with the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs began in 1946 when he became its financial adviser. In 1949 he was named to an official post in the Foreign Ministry and in 1951 became the deputy foreign minister, with cabinet rank, although he continued to remain aloof from membership in any political party. In foreign affairs he continued a policy of international economic cooperation. A diplomatic feat of this period was the avoiding of Swedish commitment to the cooperative military venture of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization while collaborating on the political level in the Council of Europe and on the economic level in the Organization of European Economic Cooperation.

Hammarskjöld represented Sweden as a delegate to the United Nations in 1949 and again from 1951 to 1953. Receiving fifty-seven votes out of sixty, Hammarskjöld was elected Secretary-General of the United Nations in 1953 for a five-year term and reelected in 1957. Before turning to the world problems awaiting him, he established a firm base of operations. For his Secretariat of 4,000 people, he drew up a set of regulations defining their responsibilities to the international organization of which they were a part and affirming their independence from narrowly conceived national interests.

In the six years after his first major victory of 1954-1955, when he personally negotiated the release of American soldiers captured by the Chinese in the Korean War, he was involved in struggles on three of the world’s continents. He approached them through what he liked to call “preventive diplomacy” and while doing so sought to establish more independence and effectiveness in the post of Secretary-General itself.

In the Middle East his efforts to ease the situation in Palestine and to resolve its problems continued throughout his stay in office. During the Suez Canal crisis of 1956, he exercised his own personal diplomacy with the nations involved; worked with many others in the UN to get the UN to nullify the use of force by Israel, France, and Great Britain following Nasser’s commandeering of the Canal; and under the UN’s mandate, commissioned the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) – the first ever mobilized by an international organization. In 1958 he suggested to the Assembly a solution to the crises in Lebanon and Jordan and subsequently directed the establishment of the UN Observation Group in Lebanon and the UN Office in Jordan, bringing about the withdrawal of the American and British troops which had been sent there. In 1959 he sent a personal representative to Southeast Asia when Cambodia and Thailand broke off diplomatic relations, and another to Laos when problems arose there.

Out of these crises came procedures and tactics new to the UN – the use of the UNEF, employment of a UN “presence” in world trouble spots and a steadily growing tendency to make the Secretary-General the executive for operations for peace.

It was with these precedents established that the United Nations and Hammarskjöld took up the problems stemming from the new independence of various developing countries. The most dangerous of these, that of the newly liberated Congo, arose in July, 1960, when the new government there, faced with mutiny in its army, secession of its province of Katanga, and intervention of Belgian troops, asked the UN for help. The UN responded by sending a peace-keeping force, with Hammarskjöld in charge of operations.

When the situation deteriorated during the year that followed, Hammarskjöld had to deal with almost insuperable difficulties in the Congo and with criticism in the UN. A last crisis for him came in September, 1961, when, arriving in Leopoldville to discuss details of UN aid with the Congolese government, he learned that fighting had erupted between Katanga troops and the noncombatant forces of the UN. A few days later, in an effort to secure a cease-fire, he left by air for a personal conference with President Tshombe of Katanga. Sometime in the night of September 17-18, he and fifteen others aboard perished when their plane crashed near the border between Katanga and North Rhodesia.2

After his death, the publication in 1963 of his “journal” entitled Markings revealed the inner man as few documents ever have. The entries in this manuscript, Hammarskjöld wrote in a covering letter to his literary executor, constitute ” a sort of White Book concerning my negotiations with myself – and with God.” There is a delicate irony in this use of the language of the diplomat. The entries themselves are spiritual truths given artistic form. Markings contains many references to death, perhaps none more explicit or significant than this portion from the opening entries, written when he was a young man:

Tomorrow we shall meet,

Death and I -.

And he shall thrust his sword

Into one who is wide awake.3

Selected Bibliography

Aulén, Gustaf, Dag Hammarskjöld’s White Book: An Analysis of “Markings”. Philadelphia, Fortress, 1969.

Cordier, Andrew W., and Kenneth L. Maxwell, eds., Paths to World Order. New York, Columbia University Press, 1967. Contains, among other Dag Hammarskjöld Memorial Lectures, “Motivations and Methods of Dag Hammarskjöld”, by Andrew W. Cordier, pp. 1-21; “Dag Hammarskjöld: The Inner Person”, by Henry P. van Dusen, pp. 22-44.

Cordier, Andrew W., and Wilder Foote, eds., The Quest for Peace: The Dag Hammarskjöld Memorial Lectures. New York, Columbia University Press, 1965. Contains The Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation., by Alva Myrdal, pp. vii-xi and, among other lectures, “Dag Hammarskjöld’s Quest for Peace”, by Mongi Slim, pp. 1-8; “The United Nations Operation in the Congo”, by Ralph J. Bunche, pp. 119-138. This volume is published in shortened form under the title Quest for Peace, Racine, Wisc., The Johnson Foundation, 1965.

Current Biography, 1953.

Foote, Wilder, ed., Servant of Peace: A Selection of the Speeches and Statements of Dag Hammarskjöld, Secretary-General of the United Nations 1953-1961. New York, Harper & Row, 1962.

Gavshon, Arthur L., The Last Days of Dag Hammarskjöld. London, Barrie & Rockliff with Pall Mall Press, 1963.

Hammarskjöld, Dag, Markings, translated by Leif Sjöberg and W.H. Auden. London, Faber and Faber, 1964; New York, Knopf, 1964. Originally published in Swedish as Vägmärken. Stockholm, Bonniers, 1963.

Kelen, Emery, Hammarskjöld. New York, Putnam, 1966.

Kelen, Emery, ed., Hammarskjöld: The Political Man. New York, Funk & Wagnalls, 1968.

Lash, Joseph P., Dag Hammarskjöld: Custodian of the Brushfire Peace. Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday, I96I.

Miller, Richard I., Dag Hammarskjöld and Crisis Diplomacy. New York, Oceana Publications, 1961. Includes bibliographical references at the end of each chapter.

Obituary, the (London) Times (September 19, 1961) 13.

Obituary and other articles, the New York Times (September 19, 1961) I, 14.

Paffrath, Leslie, The Legacy of Dag Hammarskjöld, Saturday Review (July 24, 1965) 33, 49.

Settel, T.S., ed., The Light and the Rock: The Vision of Dag Hammarskjöld. New York, Dutton, 1966.

Simon, Charlie May, Dag Hammarskjöld. New York, Dutton, 1967.

Smith, Bradford, “Dag Hammarskjöld: Peace by Juridical Sanction”, in Men of Peace, by Bradford Smith, pp. 310-345. Philadelphia, Lippincott, 1964.

Snow, C.P., “Dag Hammarskjöld”, in Variety of Men, pp. 151-168. London, Macmillan, 1967.

Stolpe, Sven, Dag Hammarskjöld: A Spiritual Portrait, English translation by Naomi Walford. New York, Scribner, 1966. Originally published in Swedish as Dag Hammarskjölds andliga väg, 1965.

Thorpe, Deryck, Hammarskjöld: Man of Peace. Ilfracombe, England, Stockwell, 1969.

Van Dusen, Henry P., Dag Hammarskjöld: The Statesman and His Faith. New York, Harper & Row, 1967. Written for Edward R. Murrow’s radio program, This I Believe, and published in a book of the same name in 1954; reprinted in Foote, Servant of Peace, pp. 23-24.

1. The story of the UN Congo mission is told in some detail in the presentation speech.

2. Not all of the details of the crash are known; for in-depth discussions see Gavshon, The Last Days of Dag Hammarskjöld and Thorpe, Hammarskjöld: Man of Peace.

3. Hammarskjöld, Markings, p. 31.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.