David Trimble was born in Bangor, Northern Ireland on 15 October 1944. He was educated at Bangor Grammar School, and graduated from Queen’s University, Belfast in 1968 with a first-class honours degree in Law …

David Trimble – Speed read

David Trimble was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, jointly with John Hume, for his efforts to find a peaceful solution to the conflict in Northern Ireland.

Full name: David Trimble

Born: 15 October 1944, Belfast, Northern Ireland

Died: 25 July 2022, Belfast, Northern Ireland

Date awarded: 16 October 1998

Protestant skilled at compromise

David Trimble, leader of the Protestant Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) in Northern Ireland, was known for his intransigence toward Catholics, but after he took over as party chairman in 1995, he initiated talks with his political opponents. Trimble negotiated with Ireland’s prime minister, his arch-enemy the IRA and the British. In 1998 he signed a peace accord that he gained majority support for within the UUP. The Good Friday Agreement called for expanded self-rule for Northern Ireland, in which both Catholics and Protestants were assured a voice. Criminal legislation would be amended, political prisoners would be released and armed factions would turn in their illegal weapons. In 1999 Trimble became first minister with a mandate to implement the peace accord.

“What we democratic politicians want in Northern Ireland is not some utopian society but a normal society. The best way to secure that normalcy is the tried and trusted method of parliamentary democracy.”

David Trimble, Nobel Prize lecture, 10 December 1998.

| Ulster Unionist Party Founded in 1905. The largest Protestant political party in Northern Ireland. Headed by David Trimble since 1995. Trimble was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1998 for negotiating a peace agreement with Catholics. |

| IRA Irish Republican Army. Founded in 1919. Played a decisive role in the war of liberation against Great Britain. Its goal is to unify Ireland. Starting in 1970, the IRA committed acts of terrorism and assassination in Northern Ireland and England. In 2000 the IRA agreed to abandon its armed struggle. |

| Good Friday Agreement Agreement between the Irish and British governments on a peaceful resolution to the conflict in Northern Ireland. Entered into on Good Friday (12 April 1998). Approved by public referendums in Ireland and Northern Ireland the same year. |

From unbendable to compromise

When David Trimble took part in the Protestant memorial march in 1995, few would have imagined that soon he would be negotiating with his longstanding enemies. Ever since the early 1970s, he had been known as an unyielding Protestant who fiercely opposed the Catholic nationalists. Just a few weeks later, Trimble, as the newly elected party chairman, met for talks with Ireland’s prime minister. He was the first unionist to set foot in the Irish parliament since the island had been partitioned. When the Good Friday Agreement was signed, he fought hard to gain majority support for the accord within the UUP.

“David Trimble has recognized that sensible compromise is the only way out of a deadlock born of hatred and outdated prejudice.”

The German radio-station Deutsche Welle, 30 May 2000.

Disarming and history. Stumbling blocks to peace

In his Nobel Prize lecture, Trimble had the following to say about the coming challenges: “There are Hills in Northern Ireland and there are mountains. The hills are decommissioning and policing. But the mountain, if we could but see it clearly, is not in front of us but behind us, in history. The dark shadow we seem to see in the distance is not really a mountain ahead, but the shadow of the mountain behind – a shadow from the past thrown forward into our future. It is a dark sludge of historical sectarianism. We can leave it behind us if we wish.”

Trimble’s parting with UUP

The massive loss of vote for the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) in the Northern Irish election of 2003 weakened David Trimble’s position as a politician. When, two years later, he also lost his seat in the British Parliament, he stood down as party leader. In 2006 Trimble was made Baron Trimble of Lisnagarvey and gained a seat in the British House of Lords. The year after, he left the UUP and joined the Conservative Party.

Peace process without David Trimble

After elections for the new provincial assembly in 2007, the two former arch enemies Gerry Adams from Sinn Fein and Ian Paisley from the Democratic Unionist Party agreed to cooperate. They formed a government and ensured that disarmament and the formation of a new police force could continue. Thus, two key elements of the Good Friday Agreement were finally fulfilled.

“Under his leadership, enough fear and suspicion was overcome to enable a majority of unionists to rally behind the Good Friday agreement.”

Francis Sejersted, Presentation speech, 10 December 1998.

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

John Hume – Speed read

John Hume was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, jointly with David Trimble, for his efforts to find a peaceful solution to the conflict in Northern Ireland.

Full name: John Hume

Born: 18 January 1937, Londonderry, Northern Ireland

Died: 3 August 2020, Londonderry, Northern Ireland

Date awarded: 16 October 1998

Civil rights advocate and European Parliament member

During Easter of 1998, the largest political parties in Northern Ireland signed the Good Friday Agreement. The man regarded as chief architect of the peace accord was John Hume, Catholic leader of the moderate Social Democratic and Labour Party. Hume, a teacher, joined the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland in the 1960s. As a member of the European Parliament and the British House of Commons, he supported expanded self-rule and a more democratic distribution of power in Northern Ireland. He also worked actively to improve contacts between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland and between London and Dublin. In particular, he sought to convince IRA leader Gerry Adams that continued armed conflict was futile. In this way, Hume laid a solid foundation for the historical peace accord.

“… the new Europe has evolved and is still evolving, based on agreement and respect for difference. That is precisely what we are now committed to doing in Northern Ireland.”

John Hume, Nobel Prize lecture, 10 December 1998.

| IRA Irish Republican Army. Founded in 1919. Played a decisive role in the war of liberation against Great Britain. Its goal is to unify Ireland. Starting in 1970, the IRA committed acts of terrorism and assassination in Northern Ireland and England. In 2000 the IRA agreed to abandon its armed struggle. |

| The European Parliament The EU’s elected legislative assembly. Seat in Strasbourg. The parliament had 736 representatives in 2011. Representatives are directly elected in the member countries in proportion to the size of the population. |

| Civil rights Equal rights for all citizens of a nation. Based on the US Declaration of Independence of 1776 and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789. |

“Hume acted as a bridge-builder between the extremes and moved the talks forward.”

The Norwegian journalist Christian Borch, November 1998.

Preparations for the Good Friday Agreement

Hume considered it crucial to involve all parties in peace negotiations. He played a key role in achieving Irish participation in the government of Northern Ireland, and he did not hesitate to contact Gerry Adams, leader of the political wing of the IRA, to convince him that continued armed conflict was pointless. When the IRA declared a ceasefire in 1989, it cleared the path of one significant obstacle to new negotiations.

| Good Friday Agreement Agreement between the Irish and British governments on a peaceful resolution to the conflict in Northern Ireland. Entered into on Good Friday (12 April 1998). Approved by public referendums in Ireland and Northern Ireland the same year. |

John Hume’s European vision

John Hume’s political experience from the European Parliament was a key driving force in his campaign for peace. As he stated in his Nobel Prize lecture: “The peoples of Europe created institutions which respected their diversity – a Council of Ministers, the European Commission and the European Parliament – but allowed them to work together in their common and substantial economic interest. They spilt their sweat and not their blood and by doing so broke down the barriers of distrust of centuries and the new Europe has evolved and is still evolving, based on agreement and respect for difference.”

“Especially during periods of escalating violence, Hume has had to swallow sometimes very harsh criticism, from within his own ranks as well as from others, for his gentle approach to the hard-liners. But with his personal integrity, Hume has stood firm, and his policy has won through.”

Francis Sejersted, Presentation speech, 10 December 1998.

Learn more

“John Hume is married to Pat and they have three daughters and two sons.

He was a leader of the non-violent Civil Rights Movement in 1968 to 1969 having established a record of community leadership through his founding role in Derry Credit Union, Derry Housing Association and his organisation of the “University for Derry” campaign” …

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

David Trimble – Photo gallery

1 (of 7) David Trimble receiving his Nobel Peace Prize from Francis Sejersted, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, at the award ceremony at Oslo City Hall on 10 December 1998.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

2 (of 7) David Trimble and John Hume after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize medal and diploma at the award ceremony in Oslo on 10 December 1998.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

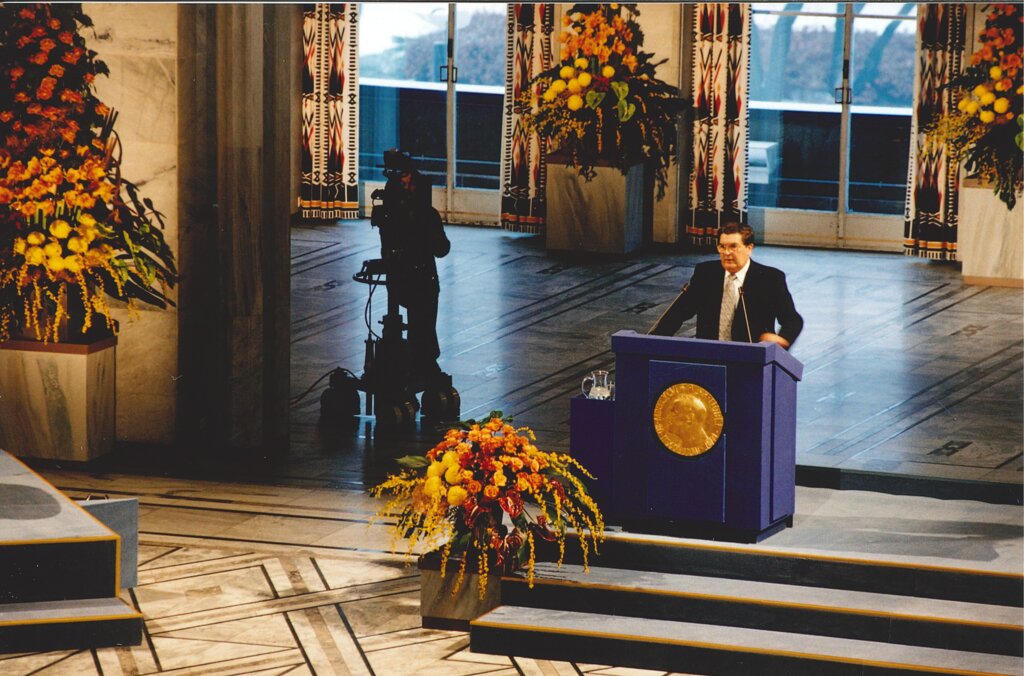

3 (of 7) David Trimble delivering his Nobel Peace Prize lecture at the award ceremony at Oslo City Hall on 10 December 1998.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

4 (of 7) Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony in the Oslo City Hall, Norway, on 10 December 1998.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

5 (of 7) David Trimble and John Hume watching photos of previos peace laureates in the Committee room at the Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo, Norway, December 1998.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

6 (of 7) David Trimble during a press conference at the Norwegian Nobel Institute, December 1998.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

7 (of 7) At the Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony on 10 December 2001 where Kofi Annan and the United Nations were awarded the 2001 peace prize, many previous laureates were present. From left: Joseph Rotblat, Jody Williams, José Ramos-Horta, Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, Lech Wałęsa, Desmond Tutu, John Hume, David Trimble, Elie Wiesel, Norman Borlaug, Rigoberta Menchu Tum and Mairead Corrigan. The remaining are representatives for peace prize awarded organisations.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

John Hume – Photo gallery

1 (of 9) John Hume receiving his Nobel Peace Prize from Francis Sejersted, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, at the award ceremony at Oslo City Hall on 10 December 1998.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

2 (of 9) John Hume showing his Nobel Peace Prize medal and diploma at the award ceremony at Oslo City Hall on 10 December 1998.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

3 (of 9) David Trimble and John Hume after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize medal and diploma at the award ceremony in Oslo on 10 December 1998.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

4 (of 9) Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony in the Oslo City Hall, Norway, on 10 December 1998.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

5 (of 9) David Trimble and John Hume watching photos of previos peace laureates in the Committee room at the Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo, Norway, December 1998.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

6 (of 9) John Hume during a press conference at the Norwegian Nobel Institute, December 1998.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

7 (of 9) Desmond Tutu, John Hume and Joseph Rotblat at the banquet for the 2001 Nobel Prize laureates UN and Kofi Annan, 10 December 2001.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

8 (of 9) Nobel Peace Prize laureates at the Nobel Centennial 2001, a conference titled ”The Conflicts of the 20th Century and the Solutions for the 21st Century”. From left: Oscar Arias Sánchez, Norman Borlaug, Joseph Rotblat, Rigoberta Menchu, Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, (photographer Micheline Pelletier), John Hume and Mairead Corrigan.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

9 (of 9) At the Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony on 10 December 2001 where Kofi Annan and the United Nations were awarded the 2001 peace prize, many previous laureates were present. From left: Joseph Rotblat, Jody Williams, José Ramos-Horta, Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, Lech Wałęsa, Desmond Tutu, John Hume, David Trimble, Elie Wiesel, Norman Borlaug, Rigoberta Menchu Tum and Mairead Corrigan. The remaining are representatives for peace prize awarded organisations.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

David Trimble – Other resources

Links to other sites

Lord Trimble’s page at UK Parliament

Biography from American Academy of Achievement

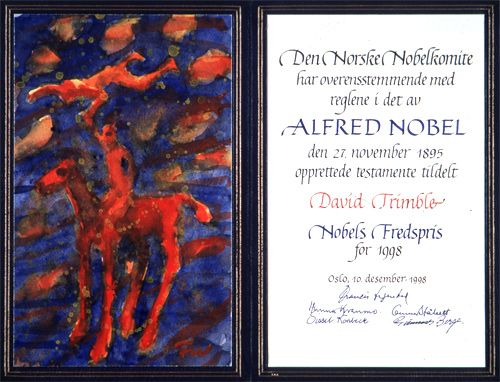

David Trimble – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1998

Artist: Franz Widerberg

Calligrapher: Inger Magnus

David Trimble – Nobel Lecture

David Trimble delivering his Nobel Peace Prize lecture.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

Nobel Lecture, Oslo, December 10, 1998

Your Majesties, Members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen.

The Nobel Prize for peace normally goes to named persons. This year the persons named are John Hume and myself, two politicians from Northern Ireland. And I am honoured, as John Hume is honoured, that my name should be so singled out.

But in one sense the singling of one or two persons, for a peace prize, must always seem something of an injustice. In Northern Ireland I could name scores of people, Unionist and nationalist, who deserve this prize far more than I do. Add to that the thousands of people who I do not know, but who have born witness, in their own lives, by carrying out what Wordsworth called, “those little nameless, unremembered acts of kindness and love”.

And since I know there are thousands of such heroes and heroines in Northern Ireland, how many more millions of peacemakers must there be in the front line of the fight for peace across the globe. People who stand in the front line for peace in all the places where there is no peace – Bosnia, Kosovo, Gaza, Cyprus, Rwanda, Angola.

Naturally it is not possible to name each and everyone of those heroes and heroines who make up the huge host of peacemakers who, even as we speak, are at work for peace around the world.

But even if it is not possible to name them we can note their presence on the peacelines around the world.

Having said that, I am at the same time, anxious to allay any fears on your part that I might fail to pick up the medal or the cheque. The people of Northern Ireland are not a people to look a gift horse in the mouth. It is imperative that I take the medal home to Northern Ireland – if only to prove that I have been to Oslo.

And the way politics work in Northern Ireland – if John Hume has a medal, it is important that I have one too.

It is a truth universally understood that there is no such thing as a free lunch. That being so, John and I are obliged to sing for our supper. In short some expect us to speak as experts and hand out advice on how to make peace.

Some old hands say that there are two ways to sing for your supper. The first and the safest course, they say, is to make a series of vague and visionary statements.

Indeed are not vague and visionary statements much the same thing? The tradition from which I come, but by which I am not confined, produced the first vernacular bible in the language of the common people, and contributed much to the scientific language of the enlightenment. It puts a great price on the precise use of words, and uses them with circumspection, so much so that our passion for precision is often confused with an indifference to idealism.

Not so. But I am personally and perhaps culturally conditioned to be sceptical of speeches which are full of sound and fury, idealistic in intention, but impossible of implementation; and I resist the kind of rhetoric which substitutes vapour for vision. Instinctively, I identify with the person who said that when he heard a politician talk of his vision, he recommended him to consult an optician!

BUT, if you want to hear of a possible Northern Ireland, not a Utopia, but a normal and decent society, flawed as human beings are flawed, but fair as human beings are fair, then I hope not to disappoint you.

The second suggestion is that either John or I, or indeed both of us, might explicate at some little length, like peace scientists so to speak, on any lessons learnt in the little laboratory of Northern Ireland as if we were scientists and the people were so much mice.

Speaking for myself, there are two good reasons to reject this course. First, I am not sure that I hold the status of scientist in the political laboratory of Northern Ireland. Indeed, there have been days, particularly recently, when I have felt much less like the scientist and very much more like the mouse!

Secondly, I have, in fact, some fairly serious reservations about the merits of using any conflict, not least Northern Ireland as a model for the study, never mind the solution, of other conflicts.

In fact if anything, the opposite is true.

Let me spell this out.

I believe that a sense of the unique, specific and concrete circumstances of any situation is the first indispensable step to solving the problems posed by that situation.

Now, I wish I could say that that insight was my own. But that insight into the central role of concrete and specific circumstance is the bedrock of the political thought of a man who is universally recognised as one of the most eminent philosophers of practical politics.

I refer, of course to the eminent eighteenth century Irish political philosopher, and brilliant British Parliamentarian, Edmund Burke.

He was the most powerful and prophetic political intellect of that century. He anticipated and welcomed the American revolution. He anticipated the dark side of the French revolution. He delved deep into the roots of that political violence, based on the false notion of the perfectibility of man, which has plagued us since the French revolution. He is claimed by both conservatives and liberals. He can be claimed by Britain and Ireland, by catholic and protestant, and indeed by the world. For Burke’s belief in the rule of law and in parliamentary democracy, is not our monopoly, but the birthright of men and women of all countries, all colours and all creeds.

But of course he has special significance for us in Ireland. Burke, the son of a protestant father and a catholic mother, was a man who in word and in deed honoured both religious traditions, recognised and respected his Irish roots and the British Parliamentary system which nursed him to the full flowering of his genius. Today as we seek to decommission not only arms and ammunition, but also hearts and minds, Burke provides us not only with a powerful role model of the pluralist Irishman, but also with a powerful role model for politicians everywhere.

Burke is the best model for what might be called politicians of the possible. Politicians who seek to make a working peace, not in some perfect world, that never was, but in this, the flawed world, which is our only workshop.

Because he is the philosopher of practical politics, not of visionary vapours, because his beliefs correspond to empirical experience, he may be a good general guide to the practical politics of peacemaking.

I shall also be calling on two other philosophers, Amos Oz, the distinguished Israeli writer who has reached out to the Arab tradition, and George Kennan, the former US Ambassador to the Soviet Union, who laid the cornerstone of post-war US foreign policy.

All three, Burke, Oz and Kennan, are particularly acute about the problems of dealing with revolutionary violence – that political, religious and racial terrorism that comes from the pursuit of what Burke called abstract virtue, the urge to make men perfect against their will.

Now these negative notes do not mean I have not good news at the end. I do. But, it would be a dereliction of duty if I only conjured up good and generous ghosts, and failed to specify the spectres at the feast.

There are fascist forces in this world. The first step to their defeat is to define them. Let me now, with the help of Burke, Oz and Kennan, locate the dark fountain of fascism from which flows most of the political, religious and racial violence which pollutes the progressive achievements of humanity.

Burke believed that the source of the pollution is the Platonic pursuit of abstract perfection, the passion to change other people’s personal, political, religious or economic views by political violence. I say Platonic because that savage pursuit of abstract perfection starts in the Western world with Plato’s Republic. It rises to a plateau with the French and Russian revolutions. It descended to new depths with the Nazis and is present in all the national, ethnic and religious conflicts current after the collapse of communism, itself the most determined and ruthless Platonic experiment in perfecting the economic system whatever the cost in human life.

Burke challenged the Platonic perfectibility doctrine whose principal protagonist was Rousseau. Rousseau regarded man as perfect and society as corrupt. Burke believed man was flawed and that society was redemptive. The Revolution tested these theories and it was Burke’s that proved the most progressive in terms of practical politics.

He has a horror of abstract notions. In 1781 he said, “Abstract liberty, like other mere abstractions, is not to be found.” Seven years later he opposed the revolution correctly predicting that the mob would be replaced by a cabal, and the cabal by a dictator.

At the end of Rousseau’s road, Burke predicted, we would find not the perfectibility of man but the gibbet and the guillotine. And so it proved. And so it proved when Stalin set out to perfect the new Soviet man. So it proved with Mao in China and Pol Pot in Cambodia. So it will prove in every conflict when perfection is sought at the point of a gun.

Amos Oz has also arrived at the same conclusion. Recently in a radio programme he was asked to define a political fanatic. He did so as follows, “A political fanatic” he said, “is someone who is more interested in you than in himself.”

At first that might seem as an altruist, but look closer and you will see the terrorist.

A political fanatic is not someone who wants to perfect himself. No, he wants to perfect you. He wants to perfect you personally, to perfect you politically, to perfect you religiously, or racially, or geographically.

He wants you to change your mind, your government, your borders. He may not be able to change your race, so he will eliminate you from the perfect equation in his mind by eliminating you from the earth.

“The Jacobins,” said Burke, “had little time for the imperfect.”

We in Northern Ireland are not free from taint.

We have a few fanatics who dream of forcing the Ulster British people into a Utopian Irish state, more ideologically Irish than its own inhabitants actually want. We also have fanatics who dream of permanently suppressing northern nationalists in a state more supposedly British than its inhabitants actually want.

But a few fanatics are not a fundamental problem. No, the problem arises if political fanatics bury themselves within a morally legitimate political movement. Then there is a double danger. The first is that we might dismiss legitimate claims for reform because of the barbarism of terrorist groups bent on revolution.

In that situation experience would suggest that the best way forward is for democrats to carry out what the Irish writer, Eoghan Harris calls acts of good authority. That is acts addressed to their own side.

Thus each reformist group has a moral obligation to deal with its own fanatics. The Serbian democrats must take on the Serbian fascists. The PLO must take on Hammas. In Northern Ireland, constitutional nationalists must take on republican dissident terrorists and constitutional Unionists must confront protestant terrorists.

There is a second danger. Sometimes in our search for a solution, we go into denial about the darker side of the fanatic, the darker side of human nature. Not all may agree, but we cannot ignore the existence of evil. Particularly that form of political evil that wants to perfect a person, a border at any cost.

Is has many faces. Some look suspiciously like the leaders of the Serbian forces wanted for massacres such as that at Srebenice, some like those wielding absolute power in Baghdad, some like those wanted for the Omagh bombing.

It worries me that there is an appeasing strand in Western politics. Sometimes it is a hope that things are not as bad as all that. Sometimes it is a hope that people can be weaned away from terror.

What we need is George Kennanís hard-headed advice to the State Department in the 1960s for dealing with the State terrorists of his time, based on his years in Moscow, “Donít act chummy with them; donít assume a community of aims with them which does not really exist; donít make fatuous gestures of goodwill.”

Let me commend on those clear words to those who sometimes seem to think that dealing with fascists is merely a game where one wonít get hurt.

My philosophers are also guides as to how best to battle against these dark forces. Here we come again to Burkeís belief that politics proceeds not by some abstract notions or by simple appeal to the past, but by close attention to the concrete detail and circumstance of the current specific situation.

“Circumstances,” says Burke, “Circumstances give in reality to every political principle, its distinguishing colour, and discriminating effect. The circumstances are what render every civil and political scheme beneficial or noxious to mankind.”

That is the nub of the matter. True I am sure of other conflicts. Previous precedents must not blind negotiators to the current circumstances. This first step away from abstraction and towards reality, should be followed by giving space for the possibilities for progress to develop.

This is what I have tried to do: to tell unionists to give things a chance to develop. Given that the Ulster British people are coming out the experience of 25 years of “armed struggle” directed against them. They have given our appeals a generous hearing. Critics say that concessions are a sign of weakness. Burke, however says, “Magnanimity in politics is not seldom the truest wisdom; and a great empire and little minds go ill together.” Prophetic words when we think of the history of the British Empire. And we are the inheritors of that intellectual tradition that encourages us to identify with the cultural alliance of the English-speaking peoples and share their political interests.

But the realisation of peace needs more than magnanimity. It requires a certain political prudence, and a willingness at times nor to be too precise or pedantic. Burke says, “It is the nature of greatness not to be exact.” Amos Oz agrees, “Inconsistency is the basis of coexistence. The heroes of tragedy driven by consistency and by righteousness, destroy each other. He who seeks total supreme justice seeks death.”

Again the warning not to aim for abstract perfection. Heaven knows, in Ulster, what I have looked for is a peace within the realms of the possible. We could only have started from where we actually were, not from where we would have liked to be.

And we have started. And we will go on. And we will go on all the better if we walk, rather than run. If we put aside fantasy and accept the flawed nature of human enterprises. Sometimes we will stumble, maybe even go back a bit. But this need not matter if in the spirit of an old Irish proverb we say to ourselves, “Tomorrow is another day”.

In not seeking perfection beyond the power of flawed man we are acting nor just within the Burkean tradition but within the broad religious consensus. Nor is this a pessimistic approach. It is one that obliges us to do our best.

Because politics is not an exact science, but partakes of human nature within the contingent circumstances of the moment, I have not pressed the paramilitaries on the details of decommissioning. Although I am under pressure from my own political community I have not insisted on precise dates quantities and manner of decommissioning. All I have asked for is a credible beginning. All I have asked for is that they say that the “war” is over. And that is proved by such a beginning. That is not too much to ask for. Nor is it too much to ask that the reformist party of nationalism, the SDLP, support me in this.

But common sense dictates that I cannot for ever convince society that real peace is at hand if there is not a beginning to the decommissioning of weapons as an earnest of the decommissioning of hearts that must follow. Any further delay will reinforce dark doubts about whether Sinn Fein are drinking from the clear stream of democracy, or is still drinking from the dark stream of fascism. It cannot for ever face both ways.

Plenty of space has been given to the paramilitaries. Now, winter is here, and there is still no sign of spring.

Like John Bunyanís Pilgrim, we politicians have been through the Slough of Despond. We have seen Doubting Castle, the owner whereof was Giant Despair. I can certainly recall passing many times through the Valley of Humiliation. And all too often we have encountered, not only on the other side, but on our own side too, “the man who could look no way but downwards, with a muckrake in his hand.”

Nevertheless, like one of Beckettís characters, “I will go on, because I must go on.”

What we democratic politicians want in Northern Ireland is not some utopian society but a normal society. The best way to secure that normalcy is the tried and trusted method of parliamentary democracy. So the Northern Ireland Assembly is the primary institutional instrument for the development of a normal society in Northern Ireland.

Like any parliament it needs to be more than a cockpit for competing victimisations. Burke said it best, “Parliament is not a congress of ambassadors from different and hostile interests; which interests each must maintain, as an agent and an advocate, against other agents and advocates; but Parliament is a deliberative assembly of one nation, with one interest, that of the whole; where not local purposes, nor local prejudices ought to guide, but the general good resulting from the general reason of the whole.”

Some critics complain that I lack “the vision thing”. But vision in its pure meaning is clear sight. That does not mean I have no dreams. I do. But I try to have them at night. By day I am satisfied if I can see the furthest limit of what is possible. Politics can be likened to driving at night over unfamiliar hills and mountains. Close attention must be paid to what the beam can reach and the next bend.

Driving by day, as I believe we are now doing, we should drive steadily, not recklessly, studying the countryside ahead, with judicious glances in the mirror. We should be encouraged by having come so far, and face into the next hill, rather than the mountain beyond. It is not that the mountain is not in my mind, but the hill has to be climbed first.

There are Hills in Northern Ireland and there are mountains. The hills are decommissioning and policing. But the mountain, if we could but see it clearly, is not in front of us but behind us, in history. The dark shadow we seem to see in the distance is not really a mountain ahead, but the shadow of the mountain behind – a shadow from the past thrown forward into our future. It is a dark sludge of historical sectarianism. We can leave it behind us if we wish.

But both communities must leave it behind, because both created it. Each thought it had good reason to fear the other. As Namier says, the irrational is not necessarily unreasonable. Ulster Unionists, fearful of being isolated on the island, built a solid house, but it was a cold house for catholics. And northern nationalists, although they had a roof over their heads, seemed to us as if they meant to burn the house down.

None of us are entirely innocent. But thanks to our strong sense of civil society, thanks to our religious recognition that none of us are perfect, thanks to the thousands of people from both sides who made countless acts of good authority, thanks to a tradition of parliamentary democracy which meant that paramilitarism never displaced politics, thanks to all these specific, concrete circumstances we, thank god, stopped short of that abyss that engulfed Bosnia, Kosovo, Somalia and Rwanda.

Thank you for this prize for peace. We have a peace of sorts in Northern Ireland. But it is still something of an armed peace. It may seem strange that we receive the reward of a race run while the race is still not quite finished. But the paramilitaries are finished. But politics is not finished. It is the bedrock to which all societies return. Because we are the only agents of change who accept man as he is and not as someone else wants him to be. The work we do may be grubby and without glamour. But is has one saving grace. It is grounded on reality and reason. What is the nature of that reason? Let Burke answer, “Political reason is computing principle: adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing, morally – and not metaphysically or mathematically – true moral denominations.”

There are two traditions in Northern Ireland. There are two main religious denominations. But there is only one true moral denomination. And it wants peace.

I am happy and honoured to accept this prize on my own behalf.

I am happy and honoured to accept this prize on behalf of all the people of Northern Ireland.

I am happy and honoured to accept the prize on behalf of all the peacemakers from throughout the British Isles and farther afield who made the Belfast Agreement that Good Friday at Stormont.

That agreement showed that the people of Northern Ireland are no petty people.

They did good work that day.

And tomorrow is now another day.

Thank you.

David Trimble – Nobel Symposia

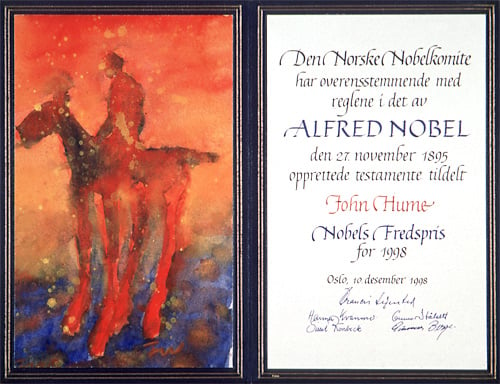

John Hume – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1998

Artist: Franz Widerberg

Calligrapher: Inger Magnus

John Hume – Nobel Lecture

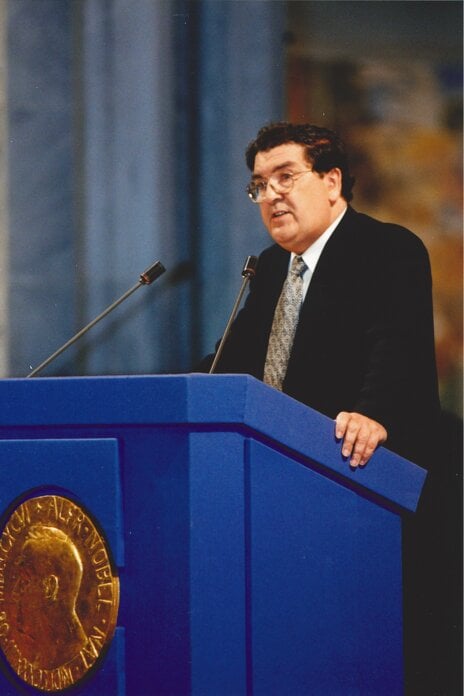

John Hume delivering his Nobel Peace Prize lecture.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

Nobel Lecture, Oslo, December 10, 1998

Your Majesties, Members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen.

I would like to begin by expressing my deep appreciation and gratitude to the Nobel committee for bestowing this honour on me today. I am sure that they share with me the knowledge that, most profoundly of all, we owe this peace to the ordinary people of Ireland, particularly those of the North who have lived and suffered the reality of our conflict. I think that David Trimble would agree with me that this Nobel prize for peace which names us both is in the deepest sense a powerful recognition from the wider world of the tremendous qualities of compassion and humanity of all the people we represent between us.

In the past 30 years of our conflict there have been many moments of deep depression and outright horror. Many people wondered whether the words of W.B Yeats might come true

“Too long a sacrifice Can make a stone of the heart.”

Endlessly our people gathered their strength to face another day and they never stopped encouraging their leaders to find the courage to resolve this situation so that our children could look to the future with a smile of hope. This is indeed their prize and I am convinced that they understand it in that sense and would take strong encouragement from today’s significance and it will powerfully strengthen our peace process.

Today also we commemorate and the world commemorates the adoption 50 years ago of the Universal declaration of Human Rights and it is right and proper, that today is also a day that is associated internationally with the support of peace and work for peace because the basis of peace and stability, in any society, has to be the fullest respect for the human rights of all its people. It is right and proper that the European Convention of Human Rights is to be incorporated into the domestic law of our land as an element of the Good Friday Agreement.

In my own work for peace, I was very strongly inspired by my European experience. I always tell this story, and I do so because it is so simple yet so profound and so applicable to conflict resolution anywhere in the world. On my first visit to Strasbourg in 1979 as a member of the European Parliament. I went for a walk across the bridge from Strasbourg to Kehl. Strasbourg is in France. Kehl is in Germany. They are very close. I stopped in the middle of the bridge and I meditated. There is Germany. There is France. If I had stood on this bridge 30 years ago after the end of the second world war when 25 million people lay dead across our continent for the second time in this century and if I had said: “Don’t worry. In 30 years’ time we will all be together in a new Europe, our conflicts and wars will be ended and we will be working together in our common interests”, I would have been sent to a psychiatrist. But it has happened and it is now clear that European Union is the best example in the history of the world of conflict resolution and it is the duty of everyone, particularly those who live in areas of conflict to study how it was done and to apply its principles to their own conflict resolution.

All conflict is about difference, whether the difference is race, religion or nationality. The European visionaries decided that difference is not a threat, difference is natural. Difference is of the essence of humanity. Difference is an accident of birth and it should therefore never be the source of hatred or conflict. The answer to difference is to respect it. Therein lies a most fundamental principle of peace – respect for diversity.

The peoples of Europe then created institutions which respected their diversity – a Council of Ministers, the European Commission and the European Parliament – but allowed them to work together in their common and substantial economic interest. They spilt their sweat and not their blood and by doing so broke down the barriers of distrust of centuries and the new Europe has evolved and is still evolving, based on agreement and respect for difference.

That is precisely what we are now committed to doing in Northern Ireland. Our Agreement, which was overwhelmingly endorsed by the people, creates institutions which respect diversity but ensure that we work together in our common interest. Our Assembly is proportionately elected so that all sections of our people are represented. Any new administration or government will be proportionately elected by the members of the Assembly so that all sections will be working together. There will be also be institutions between both parts of Ireland and between Britain and Ireland that will also respect diversity and work the common ground.

Once these institutions are in place and we begin to work together in our very substantial common interests, the real healing process will begin and we will erode the distrust and prejudices of our past and our new society will evolve, based on agreement and respect for diversity. The identities of both sections of our people will be respected and there will be no victory for either side.

We have also had enormous solidarity and support from right across the world which has strengthened our peace process. We in Ireland appreciate this solidarity and support – from the United States, from the European Union, from friends around the world – more than we can say. The achievement of peace could not have been won without this goodwill and generosity of spirit. We should recall too on this formal occasion that our Springtime of peace and hope in Ireland owes an overwhelming debt to several others who devoted their passionate intensity and all of their skills to this enterprise: to the Prime Ministers, Tony Blair and Bertie Ahern, to the President of the United States of America Bill Clinton and the European President Jacques Delors and Jacques Santer and to the three men who so clearly facilitated the negotiation, Senator George Mitchell former Leader of the Senate of the United States of America, Harri Holkerri of Finland and General John de Chastelain of Canada. And, of course, to our outstanding Secretary of State, Mo Mowlam.

We in Ireland appreciate this solidarity and support – from the United States; from the European Union, from friends around the world – more than we can say. The achievement of peace could not have been won without this good will and generosity of spirit. Two major political traditions – share the Island of Ireland. We are destined by history to live side by side. Two representatives of these political traditions stand here today. We do so in shared fellowship and a shared determination to make Ireland, after the hardship and pain of many years, a true and enduring symbol of peace.

Too many lives have already been lost in Ireland in the pursuit of political goals. Bloodshed for political change prevents the only change that truly matter: in the human heart. We must now shape a future of change that will be truly radical and that will offer a focus for real unity of purpose: harnessing new forces of idealism and commitment for the benefit of Ireland and all its people.

Throughout my years in political life, I have seen extraordinary courage and fortitude by individual men and women, innocent victims of violence. Amid shattered lives, a quiet heroism has born silent rebuke to the evil that violence represents, to the carnage and waste of violence, to its ultimate futility.

I have seen a determination for peace become a shared bond that has brought together people of all political persuasions in Northern Ireland and throughout the island of Ireland.

I have seen the friendship of Irish and British people transcend, even in times of misunderstanding and tensions, all narrower political differences. We are two neighbouring islands whose destiny is to live in friendship and amity with each other. We are friends and the achievement of peace will further strengthen that friendship and, together, allow us to build on the countless ties that unite us in so many ways.

The Good Friday Agreement now opens a new future for all the people of Ireland. A future built on respect for diversity and for political difference. A future where all can rejoice in cherished aspirations and beliefs and where this can be a badge of honour, not a source of fear or division.

The Agreement represents an accommodation that diminishes the self-respect of no political tradition, no group, no individual. It allows all of us – in Northern Ireland and throughout the island of Ireland – to now come together and, jointly, to work together in shared endeavour for the good of all.

No-one is asked to yield their cherished convictions or beliefs. All of us are asked to respect the views and rights of others as equal of our own and, together, to forge a covenant of shared ideals based on commitment to the rights of all allied to a new generosity of purpose.

That is what a new, agreed Ireland will involve. That is what is demanded of each of us.

The people of Ireland, in both parts of the island, have joined together to passionately support peace. They have endorsed, by overwhelming numbers in the ballot box, the Good Friday Agreement. They have shown an absolute and unyielding determination that the achievement of peace must be set in granite and its possibilities grasped with resolute purpose.

It is now up to political leaders on all sides to move decisively to fulfil the mandate given by the Irish people: to safeguard and cherish peace by establishing agreed structures for peace that will forever remove the underlying causes of violence and division on our island. There is now, in Ireland, a passionate sense of moving to new beginnings.

I salute all those who made this possible: the leaders and members of all the political parties who worked together to shape a new future and to reach agreement; the Republican and Loyalist movements who turned to a different path with foresight and courage; people in all parts of Ireland who have led the way for peace and who have made it possible.

And so, the challenge now is to grasp and shape history: to show that past grievances and injustices can give way to a new generosity of spirit and action.

I want to see Ireland – North and South – the wounds of violence healed, play its rightful role in a Europe that will, for all Irish people, be a shared bond of patriotism and new endeavour.

I want to see Ireland as an example to men and women everywhere of what can be achieved by living for ideals, rather than fighting for them, and by viewing each and every person as worthy of respect and honour.

I want to see an Ireland of partnership where we wage war on want and poverty, where we reach out to the marginalised and dispossessed, where we build together a future that can be as great as our dreams allow.

The Irish poet, Louis MacNiece wrote words of affirmation and hope that seem to me to sum up the challenges now facing all of us – North and South, Unionist and Nationalist – in Ireland.

“By a high star our course is set, Our end is life. Put out to sea.”

That is the journey on which we in Ireland are now embarked.

Today, as I have said, the world also commemorates the adoption fifty years ago, of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. To me there is a unique appropriateness, a sort of poetic fulfilment, in the coincidence that my fellow Laureate and I, representing a community long divided by the forces of a terrible history, should jointly be honoured on this day. I humbly accept this honour on behalf of a people who, after many years of strife, have finally made a commitment to a better future in harmony together. Our commitment is grounded in the very language and the very principles of the Universal Declaration itself. No greater honour could have been done me or the people I speak here for on no more fitting day.

I will now end with a quotation of total hope, the words of a former Laureate, one of my great heroes of this century, Martin Luther King Jr.

We shall overcome.

Thank you.