Malala Yousafzai was born on July 12, 1997, in Mingora, the largest city in the Swat Valley in what is now the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province of Pakistan …

Malala Yousafzai – Speed read

Malala Yousafzai was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, jointly with Kailash Satyarthi, for her struggle against the suppression of children and young people and for the right of all children to education.

Full name: Malala Yousafzai

Born: 12 July 1997, Mingora, Pakistan

Date awarded: 10 October 2014

“Pens are mightier than weapons”

Malala Yousafzai comes from the Swat Valley in Pakistan. In 2009 the Taliban decreed that all girls’ schools should be closed or there would be consequences. Malala continued to go to school. She started to blog about girls’ right to education, and became known as one who defied the school ban. On 9 October 2012 she was shot by the Taliban, but survived. She has not allowed threats to silence her and is a global voice as she continues to campaign for the right of girls to education. The Malala Fund helps to provide schooling for girls in Pakistan, Nigeria, Jordan and Kenya. Her message has been that children’s right to education is the foundation for peace, and an important measure in the fight against extremism. Aged just 17, Malala is the youngest ever Nobel Prize laureate.

“The extremists are afraid of books and pens. The power of education frightens them.”

Malala Yousafzai, speech at the United Nations, 12 July 2013.

From the Nobel Committee’s announcement

“The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided that the Nobel Peace Prize for 2014 is to be awarded to Kailash Satyarthi and Malala Yousafzai for their struggle against the suppression of children and young people and for the right of all children to education. (…) Despite her youth, Malala Yousafzai has already fought for several years for the right of girls to education, and has shown by example that children and young people, too, can contribute to improving their own situations. This she has done under the most dangerous circumstances. Through her heroic struggle she has become a leading spokesperson for girls’ rights to education.”

The voice from Swat

Malala has become the very symbol of girls’ right to education. At the age of 11 she became known for her blog on the BBC’s Urdu service and attracted international media attention. The world was appalled by the attempt to assassinate her in 2012, but Malala recovered and forgave her attacker. Political leaders and celebrities have paid tribute to the Pakistani schoolgirl and have endorsed her message that every child is entitled to go to school. The campaign “I am Malala” was launched to promote her cause. On Malala’s 16th birthday, 12 July 2013, she addressed the UN, which responded by naming the day “Malala Day”.

“Education is education. We should learn everything and then choose which path to follow. Education is neither Eastern nor Western, it is human.”

Malala Yousafzai, in her book I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban.

Education is a human right

Articles 28 and 29 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child state that all children are entitled to an education. Education should aim to develop the child’s personality, talents, physical and mental capacities and be of good quality. UNESCO says that, worldwide, 57 million children do not go to school, over half of them girls. As many as 130 million children spend years at school without ever learning to read or write. Education helps to reduce child mortality, improves health, increases an understanding of democracy, results in higher wages and promotes economic growth.

| UN convention on the rights of the child Adopted in 1959 to give children particular protection so that they can grow up safely, no matter where in the world they live. Children shall be ensured access to food, shelter and education, and shall be protected from participation in child labour. |

| UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. Founded in 1946. Noted especially for its efforts to promote literacy. |

“I raise my voice not so that I can shout, but so that those without a voice can be heard.”

Malala Yousafzai, speech at the United Nations, 12 July 2013.

Two sides of the same cause?

The Nobel Peace Prize to Kailash Satyarthi and Malala Yousafzai is an award both for human rights and humanitarian work. With this prize the Norwegian Nobel Committee wishes to build a bridge between nations, religions and generations. Kailash Satyarthi is a 60-year-old Hindu from India, while Malala Yousafzai is a 17-year-old Muslim from Pakistan. The two peace prize laureates work in different arenas, but are bound together in the fight for children’s rights and the goal of enabling every child to go to school. Both are supporters of non-violence, even in the face of threats and attacks by their opponents.

“I don’t want revenge on the Taliban. I want education for sons and daughters of the Taliban.”

Malala Yousafzai, in her book ‘I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban’.

Learn more

Nobel Prize lecture

“When my world suddenly changed, my priorities changed too. I had two options. One was to remain silent and wait to be killed. And the second was to speak up and then be killed.”

In her Nobel Prize lecture Malala Yousafzai spoke up for every child’s right to go to school. Read the lecture here

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Malala Yousafzai – Facts

Malala Yousafzai – Biographical

Malala Yousafzai was born on July 12, 1997, in Mingora, the largest city in the Swat Valley in what is now the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province of Pakistan. She is the daughter of Ziauddin and Tor Pekai Yousafzai and has two younger brothers.

At a very young age, Malala developed a thirst for knowledge. For years her father, a passionate education advocate himself, ran a learning institution in the city, and school was a big part of Malala’s family. She later wrote that her father told her stories about how she would toddle into classes even before she could talk and acted as if she were the teacher.

In 2007, when Malala was ten years old, the situation in the Swat Valley rapidly changed for her family and community. The Taliban began to control the Swat Valley and quickly became the dominant socio-political force throughout much of northwestern Pakistan. Girls were banned from attending school, and cultural activities like dancing and watching television were prohibited. Suicide attacks were widespread, and the group made its opposition to a proper education for girls a cornerstone of its terror campaign. By the end of 2008, the Taliban had destroyed some 400 schools.

Determined to go to school and with a firm belief in her right to an education, Malala stood up to the Taliban. Alongside her father, Malala quickly became a critic of their tactics. “How dare the Taliban take away my basic right to education?” she once said on Pakistani TV.

In early 2009, Malala started to blog anonymously on the Urdu language site of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). She wrote about life in the Swat Valley under Taliban rule, and about her desire to go to school. Using the name “Gul Makai,” she described being forced to stay at home, and she questioned the motives of the Taliban.

Malala was 11 years old when she wrote her first BBC diary entry. Under the blog heading “I am afraid,” she described her fear of a full-blown war in her beautiful Swat Valley, and her nightmares about being afraid to go to school because of the Taliban.

Pakistan’s war with the Taliban was fast approaching, and on May 5, 2009, Malala became an internally displaced person (IDP), after having been forced to leave her home and seek safety hundreds of miles away.

On her return, after weeks of being away from Swat, Malala once again used the media and continued her public campaign for her right to go to school. Her voice grew louder, and over the course of the next three years, she and her father became known throughout Pakistan for their determination to give Pakistani girls access to a free quality education. Her activism resulted in a nomination for the International Children’s Peace Prize in 2011. That same year, she was awarded Pakistan’s National Youth Peace Prize. But, not everyone supported and welcomed her campaign to bring about change in Swat. On the morning of October 9, 2012, 15-year-old Malala Yousafzai was shot by the Taliban.

Seated on a bus heading home from school, Malala was talking with her friends about schoolwork. Two members of the Taliban stopped the bus. A young bearded Talib asked for Malala by name, and fired three shots at her. One of the bullets entered and exited her head and lodged in her shoulder. Malala was seriously wounded. That same day, she was airlifted to a Pakistani military hospital in Peshawar and four days later to an intensive care unit in Birmingham, England.

Once she was in the United Kingdom, Malala was taken out of a medically induced coma. Though she would require multiple surgeries, including repair of a facial nerve to fix the paralyzed left side of her face, she had suffered no major brain damage. In March 2013, after weeks of treatment and therapy, Malala was able to begin attending school in Birmingham.

After the shooting, her incredible recovery and return to school resulted in a global outpouring of support for Malala. On July 12, 2013, her 16th birthday, Malala visited New York and spoke at the United Nations. Later that year, she published her first book, an autobiography entitled “I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban.” On October 10, 2013, in acknowledgement of her work, the European Parliament awarded Malala the prestigious Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought.

In 2014, through the Malala Fund, the organization she co-founded with her father, Malala traveled to Jordan to meet Syrian refugees, to Kenya to meet young female students, and finally to northern Nigeria for her 17th birthday. In Nigeria, she spoke out in support of the abducted girls who were kidnapped earlier that year by Boko Haram, a terrorist group which, like the Taliban, tries to stop girls from going to school.

In October 2014, Malala, along with Indian children’s rights activist Kailash Satyarthi, was named a Nobel Peace Prize winner. At age 17, she became the youngest person to receive this prize. Accepting the award, Malala reaffirmed that “This award is not just for me. It is for those forgotten children who want education. It is for those frightened children who want peace. It is for those voiceless children who want change.”

Today, the Malala Fund has become an organization that, through education, empowers girls to achieve their potential and become confident and strong leaders in their own countries. Funding education projects in six countries and working with international leaders, the Malala Fund joins with local partners to invest in innovative solutions on the ground and advocates globally for quality secondary education for all girls.

Currently residing in Birmingham, Malala is an active proponent of education as a fundamental social and economic right. Through the Malala Fund and with her own voice, Malala Yousafzai remains a staunch advocate for the power of education and for girls to become agents of change in their communities.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Malala Yousafzai – Photo gallery

Nobel Peace Prize Laureates Malala Yousafzai and Kailash Satyarthi at the Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony at the Oslo City Hall in Norway, 10 December 2014. To the far left: Thorbjørn Jagland, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2014, Photo: Ken Opprann

Malala Yousafzai and Kailash Satyarthi showing their Nobel medals and diplomas during the Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony at the Oslo City Hall in Norway, 10 December 2014.

© The Nobel Foundation 2014. Photo: Ken Opprann

Malala Yousafzai's message in the guestbook of the Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo, Norway. She wrote it during her visit there on 9 December 2014.

Photo: The Norwegian Nobel Institute

Malala Yousafzai and Kailash Satyarthi during a visit to the Norwegian Nobel Committee, 10 December 2014.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2014 Photo: Ken Opprann

Kailash Satyarthi and Malala Yousafzai at the opening of the exhibition "Malala and Kailash" at the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo, Norway on 11 December 2014.

Copyright © Nobel Peace Center 2014 Photo: Johannes Granseth

The school uniform Malala Yousafzai wore when she was shot in the head by a Taliban gunman in October 2012 shown at the exhibition "Malala and Kailash" at the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo.

Copyright © Nobel Peace Center 2014 Photo: Johannes Granseth

Malala Yousafzai – Nobelforedrag

English

English (pdf, 291 kB)

Norwegianf

Nobelforedrag av Malala Yousafzai, Oslo, 10. desember, 2014.

Bismillah hir rahman ir rahim.

I Guds den nådefulle og mest velgjørendes navn.

Deres Majesteter, ærede medlemmer av Den norske Nobelkomiteen, kjære søstre og brødre. Dagen i dag er en svært lykkelig dag for meg. Jeg er beæret over at Nobelkomiteen har valgt meg som mottaker av denne prestisjefylte prisen.

Jeg vil takke dere alle for deres vedvarende støtte og kjærlighet. Jeg er takknemlig for alle brevene og kortene som jeg fortsatt mottar fra hele verden. Å lese de varme og oppmuntrende ordene fra dere både styrker og inspirerer meg.

Jeg vil takke mine foreldre for deres uforbeholdne kjærlighet. Jeg vil takke faren min for at han ikke vingeklippet meg og lot meg fly. Jeg vil takke moren min for at hun har inspirert meg til å bli tålmodig og til å alltid si sannheten – noe vi er overbevist om er islams egentlige budskap.

Jeg er stolt over å være den første pashtuner, den første pakistaner og den første ungdommen som mottar denne prisen. Jeg er ganske sikker på at jeg også er den første mottakeren av Nobels fredspris som fortsatt kjemper sammen med sine yngre brødre. Jeg vil at det skal bli fred over alt, men det er noe mine brødre og jeg fortsatt jobber med.

Jeg er også beæret over å motta denne prisen sammen med Kailash Satyarthi, som har vært en forkjemper barns rettigheter over lang tid. Faktisk dobbelt så lenge som jeg har levd. Jeg er også glad for at vi kan stå sammen og vise verden at en inder og en pakistaner kan forenes i fred og i arbeidet for barns rettigheter.

Kjære brødre og søstre, jeg er oppkalt etter pashtunernes egen Jeanne d’Arc og store inspirasjonskilde, Malalai av Maiwand. Ordet Malala betyr “sorgtynget”, “trist”, men for å tilføre det litt lykke brukte bestefaren min alltid å kalle meg Malala – Verdens lykkeligste jente og i dag er jeg veldig lykkelig over at vi står her sammen for en viktig sak.

Denne prisen går ikke bare til meg. Den går til de glemte barna som ønsker seg utdanning. Den går til de redde barna som ønsker seg fred. Den går til de stemmeløse barna som ønsker seg endring.

Jeg er her for å forsvare deres rettigheter, være deres stemme … dette er ikke en tid for å synes synd på dem. Dette er en tid for å handle slik at dette blir den siste gangen vi opplever at et barn blir fratatt retten til utdanning.

Jeg har oppdaget at folk beskriver meg på mange ulike måter.

Noen kaller meg jenta som ble skutt av Taliban

Noen kaller meg jenta som kjempet for sine rettigheter

Og enkelte kaller meg en “Nobelprisvinner” nå

Slik jeg ser det, er jeg bare en engasjert og egenrådig person som ønsker at alle barn skal få god utdanning, at det skal være like rettigheter for kvinner og menn og at det skal bli fred over hele kloden.

Utdanning er en av livets velsignelser—og en av livets nødvendigheter. Det er noe jeg har erfart i løpet av de 17 årene jeg har levd. I mitt hjem i Swat-dalen i det nordlige Pakistan elsket jeg å gå på skolen og lære meg nye ting. Jeg husker at jeg og venninnene mine dekorerte hendene våre med hennamaling ved spesielle anledninger. I stedet for å tegne blomster og mønstre, malte vi matematiske formler og ligninger på hendene våre.

Vi tørstet etter utdanning fordi vår fremtid lå nettopp der, i det klasserommet. Vi brukte å sitte og lese og lære ting sammen. Vi elsket våre rene og fine skoleuniformer og vi satt der og drømte store drømmer. Vi ønsket å gjøre våre foreldre stolte og bevise at vi kunne utmerke oss i våre studier og oppnå ting som enkelte mener det bare er gutter kan oppnå.

Men tingene forandret seg. Da jeg var ti, ble Swat, som var et vakkert sted og et turistmål, plutselig til et sted for terrorisme. Over 400 skoler ble ødelagt. Jenter ble forhindret i å gå på skole. Kvinner ble pisket. Uskyldige mennesker ble drept. Alle led under dette og våre vakre drømmer ble til mareritt.

Utdanning gikk fra å være en rettighet til å bli en forbrytelse.

Men da min verden plutselig forandret seg, forandret også mine prioriteringer seg.

Jeg hadde to alternativer, det ene var å tie og vente på å bli drept. Det andre var å ta til motmæle og så bli drept. Jeg valgte det andre alternativet. Jeg bestemte meg for å ta til motmæle.

Terroristene forsøkte å stanse oss og de angrep meg og vennene mine 9. oktober 2012, men kulene deres kunne ikke vinne.

Vi overlevde. Og siden den dagen har stemmene våre blitt stadig sterkere.

Når jeg forteller historien min er det ikke fordi den er unik, men fordi den ikke er det.

Den er historien til mange jenter.

I dag forteller jeg deres historie også. Her i Oslo har jeg med meg noen av mine søstre som deler denne historien med meg, venner fra Pakistan, Nigeria og Syria. Mine modige søstre Shazia og Kainat Riaz som også ble skutt den dagen i Swat-dalen sammen med meg. Det var også en traumatisk opplevelse for dem. Det samme gjelder for min søster Kainat Somro fra Pakistan, som ble utsatt for ekstrem vold og misbruk, broren hennes ble til og med drept, men hun bukket ikke under.

Andre jenter som er sammen med meg her har jeg truffet under kampanjen for Malala-fondet, og de er nå blitt som søstre for meg. Min modige 16 år gamle søster Mezon fra Syria, som bor i en flyktningeleir i Jordan og som går fra telt til telt for å hjelpe jenter og gutter som ønsker å lære. Og min søster Amina, fra det nordlige Nigeria, hvor Boko Haram truer og kidnapper jenter bare fordi de ønsker å gå på skole.

Selv om jeg står foran dere her som én jente, én person – 1.57 m høy når jeg går med høye hæler – er jeg ikke én stemme, jeg er mange.

Jeg er Shazia.

Jeg er Kainat Riaz.

Jeg er Kainat Somro.

Jeg er Mezon.

Jeg er Amina. Jeg er alle disse 66 millioner jentene som ikke går på skole.

Folk spør meg ofte hvorfor det spesielt viktig at jenter får utdanning. Svaret mitt er alltid det samme.

Det jeg har lært av de to første kapitlene i den Hellige Koranen er ordet Iqra, som betyr “les” og ordet nun wal-qalam, som betyr “med pennen”

Derfor sier jeg det samme her som jeg sa i FN i fjor, nemlig at “Ett barn, én lærer, én penn og én bok kan forandre verden.”

I dag ser vi at det er rask fremgang, modernisering og utvikling i den ene halvdelen av verden, mens det samtidig er land hvor millioner av mennesker fortsatt lider under gamle problemer som sult, fattigdom, urettferdighet og konflikter.

I 2014 har vi markert hundreårsjubileet for starten av første verdenskrig, men vi har fremdeles ikke tatt full lærdom av tapet av flere millioner menneskeliv for hundre år siden.

Det er fortsatt konflikter hvor flere hundre tusen uskyldige mennesker har mistet livet. Mange familier er blitt flyktninger i Syria, Gaza og Irak. Det finnes fortsatt jenter som ikke har frihet til å gå på skole i det nordlige Nigeria. I Pakistan og Afghanistan ser vi at uskyldige mennesker blir drept i selvmordsangrep og bombeeksplosjoner.

Mange barn i Afrika får ikke mulighet til å gå på skole på grunn av fattigdom.

Mange barn i India og Pakistan er fratatt retten til skolegang på grunn av sosiale tabuer, eller fordi de er tvunget inn i barnearbeid eller fordi jenter er tvunget inn i barneekteskap.

En av mine gode skolevenninner som er like gammel som meg, var en gang i tiden en modig og selvsikker jente, som drømte om å bli lege. Men denne drømmen ble det aldri noe av. Da hun var 12 ble hun tvunget til å gifte seg og hun fikk raskt en sønn i en alder av bare 14 år, mens hun selv var et barn. Jeg vet at venninnen min ville ha blitt en veldig dyktig lege.

Men det gikk ikke … fordi hun var jente.

Hennes historie er grunnen til at jeg gir prispengene for Nobelprisen til Malala-fondet, som bidrar til god utdanning for jenter rundt om i verden og som oppfordrer verdens ledere til å hjelpe jenter som meg, Mezun og Amina. Det første stedet disse pengene vil gå til er det stedet hvor jeg har hjertet mitt, til å bygge skoler i Pakistan – og spesielt mitt hjemsted Swat og Shangla.

I min landsby er det fortsatt ingen ungdomsskole eller videregående skole for jenter. Jeg ønsker å bygge en slik skole for at mine venner skal kunne skaffe seg en utdanning – og dermed få muligheten til å oppfylle sine drømmer.

Det er der jeg vil begynne, men det stopper ikke der. Jeg vil fortsette denne kampen inntil jeg ser at alle barn går på skole. Jeg føler meg mye sterkere etter at jeg ble utsatt for dette angrepet, fordi jeg vet at ingen kan stoppe meg, eller oss, for nå er vi flere millioner som kjemper sammen.

Kjære brødre og søstre, oppe på denne scenen har det stått sterke mennesker som har skapt endring, som Martin Luther King og Nelson Mandela, Mor Teresa og Aung San Suu Kyi. Jeg håper de skrittene Kailash Satyarthi og jeg har tatt så langt og vil ta videre på denne reisen også vil føre til endring – varig endring.

Mitt store håp er at dette er siste gangen vi er nødt til å kjempe for utdanning for våre barn. Vi vil at alle skal stå sammen og støtte oss i vår kamp slik at vi kan få løst dette én gang for alle.

Som jeg sa har vi allerede tatt mange skritt i riktig retning. Nå er tiden inne for å ta et sprang.

Tiden i dag skal ikke brukes til å fortelle verdens ledere hvor viktig utdanning er – det vet de allerede – deres egne barn går på gode skoler. Nå er tiden inne for å mane dem til handling.

Vi ber verdens ledere om å stå sammen for å gi utdanning høyeste prioritet.

For femten år siden vedtok verdens ledere et sett av globale målsetninger, nemlig tusenårsmålene for utvikling. I årene etter har vi sett en viss fremgang. Antall barn som ikke går på skole er blitt halvert. Verden har imidlertid bare hatt fokus på å bygge ut barneskoler, og fremskrittet har ikke nådd ut til alle.

Neste år, i 2015, skal representanter fra hele verden møtes i FN for å vedta det neste settet av målsetninger, målsetninger for en bærekraftig utvikling. Der vil verdens ambisjoner for kommende generasjoner bli fastlagt. Lederne må benytte denne anledningen til å garantere at alle verdens barn skal få gratis kvalitetsutdanning som dekker både grunnskole, ungdomsskole og videregående skole.

Noen vil si at dette er upraktisk, eller for dyrt eller for vanskelig, eller til og med umulig. Men det er på tide at verden tenker større.

Kjære brødre og søstre, den såkalte voksne verden kan kanskje forstå det, men vi som barn kan ikke forstå det. Hvordan kan det ha seg at de landene som vi kaller “sterke” er så flinke til å skape krig, men så dårlige til å skape fred? Hvordan kan det ha seg at det er så enkelt å gi bort våpen, men så vanskelig å gi bort bøker? Hvordan kan det ha seg at det er så enkelt å bygge stridsvogner, men så vanskelig å bygge skoler?

Nå lever vi i den moderne tidsalderen, det 21. århundre, og vi tror alle at ingenting er umulig. Vi kan reise til månen og snart kan vi kanskje lande på Mars. I dette 21. århundre må vi være fast bestemt på at kvalitetsudanning til alle også vil bli en realitet.

Så la oss skape likhet, rettferdighet og fred for alle. Vi må alle bidra, ikke bare politikerne og verdens ledere, men også du og jeg. Det er vår plikt.

Så vi må sette i gang med å jobbe … og ikke vente.

Jeg oppfordrer også alle andre barn rundt om i verden til å reise seg for kjempe.

Kjære søstre og brødre, la oss bli den første generasjonen som bestemmer seg for å bli den siste.

De tomme klasserommene, den tapte barndommen, det bortkastede potensialet – måtte disse tingene ta slutt med oss.

La dette bli siste gangen en gutt eller jente tilbringer barndommen sin på en fabrikk.

La dette bli siste gangen en jente tvinges inn i et barneekteskap.

La dette bli siste gangen et uskyldig barn mister livet i en krig.

La dette bli siste gangen et klasserom står tomt.

La dette bli siste gangen en jente får høre at utdanning er en forbrytelse og ikke en rettighet.

La dette bli siste gangen et barn ikke går på skole.

La oss starte med at denne avslutningen.

La dette ta slutt med oss.

Og la oss bygge en bedre fremtid her og nå.

Takk.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2014

Malala Yousafzai – Other resources

Links to other sites

BBC News: Profile: Malala Yousafzai

TED Talks: ‘My daughter, Malala’ by Ziauddin Yousafzai

Videos

Honouring Malala Yousafzai’s own wish, the school uniform she wore when she was shot in the head by a Taliban gunman in October 2012, became part of the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize exhibition ‘Malala and Kailash’ at the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo, Norway. Here, Malala answers the question “What does this school uniform mean to you?”

At the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo, Norway, Malala Yousafzai answers the question “How do you believe the Nobel Peace Prize will affect your work?”

Geir Lundestad, Director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute and Permanent Secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, lectures on the reasons for awarding the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize to Kailash Satyarthi and Malala Yousafzai at the Nobel Peace Center, 11 October 2014.

Thorbjørn Jagland, leader of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, lectures (in Norwegian) on the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize at the Nobel Peace Center, 11 October 2014.

Malala Yousafzai – Nobel Lecture

English

English (pdf, 291 kB)

Norwegian

Nobel Lecture by Malala Yousafzai, Oslo, 10 December 2014.

Bismillah hir rahman ir rahim.

In the name of God, the most merciful, the most beneficent.

Your Majesties, Your royal highnesses, distinguished members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee,

Dear sisters and brothers, today is a day of great happiness for me. I am humbled that the Nobel Committee has selected me for this precious award.

Thank you to everyone for your continued support and love. Thank you for the letters and cards that I still receive from all around the world. Your kind and encouraging words strengthens and inspires me.

I would like to thank my parents for their unconditional love. Thank you to my father for not clipping my wings and for letting me fly. Thank you to my mother for inspiring me to be patient and to always speak the truth – which we strongly believe is the true message of Islam. And also thank you to all my wonderful teachers, who inspired me to believe in myself and be brave.

I am proud, well in fact, I am very proud to be the first Pashtun, the first Pakistani, and the youngest person to receive this award. Along with that, along with that, I am pretty certain that I am also the first recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize who still fights with her younger brothers. I want there to be peace everywhere, but my brothers and I are still working on that.

I am also honoured to receive this award together with Kailash Satyarthi, who has been a champion for children’s rights for a long time. Twice as long, in fact, than I have been alive. I am proud that we can work together, we can work together and show the world that an Indian and a Pakistani, they can work together and achieve their goals of children’s rights.

Dear brothers and sisters, I was named after the inspirational Malalai of Maiwand who is the Pashtun Joan of Arc. The word Malala means grief stricken”, sad”, but in order to lend some happiness to it, my grandfather would always call me Malala – The happiest girl in the world” and today I am very happy that we are together fighting for an important cause.

This award is not just for me. It is for those forgotten children who want education. It is for those frightened children who want peace. It is for those voiceless children who want change.

I am here to stand up for their rights, to raise their voice… it is not time to pity them. It is not time to pity them. It is time to take action so it becomes the last time, the last time, so it becomes the last time that we see a child deprived of education.

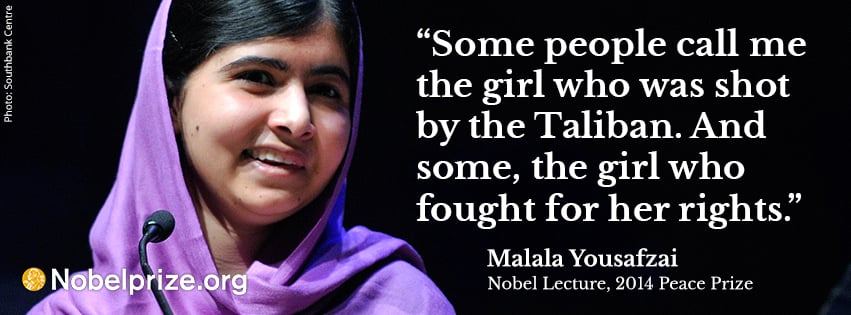

I have found that people describe me in many different ways.

Some people call me the girl who was shot by the Taliban.

And some, the girl who fought for her rights.

Some people, call me a “Nobel Laureate” now.

However, my brothers still call me that annoying bossy sister. As far as I know, I am just a committed and even stubborn person who wants to see every child getting quality education, who wants to see women having equal rights and who wants peace in every corner of the world.

Education is one of the blessings of life—and one of its necessities. That has been my experience during the 17 years of my life. In my paradise home, Swat, I always loved learning and discovering new things. I remember when my friends and I would decorate our hands with henna on special occasions. And instead of drawing flowers and patterns we would paint our hands with mathematical formulas and equations.

We had a thirst for education, we had a thirst for education because our future was right there in that classroom. We would sit and learn and read together. We loved to wear neat and tidy school uniforms and we would sit there with big dreams in our eyes. We wanted to make our parents proud and prove that we could also excel in our studies and achieve those goals, which some people think only boys can.

But things did not remain the same. When I was in Swat, which was a place of tourism and beauty, suddenly changed into a place of terrorism. I was just ten that more than 400 schools were destroyed. Women were flogged. People were killed. And our beautiful dreams turned into nightmares.

Education went from being a right to being a crime.

Girls were stopped from going to school.

When my world suddenly changed, my priorities changed too.

I had two options. One was to remain silent and wait to be killed. And the second was to speak up and then be killed.

I chose the second one. I decided to speak up.

We could not just stand by and see those injustices of the terrorists denying our rights, ruthlessly killing people and misusing the name of Islam. We decided to raise our voice and tell them: Have you not learnt, have you not learnt that in the Holy Quran Allah says: if you kill one person it is as if you kill the whole humanity?

Do you not know that Mohammad, peace be upon him, the prophet of mercy, he says, do not harm yourself or others”.

And do you not know that the very first word of the Holy Quran is the word Iqra”, which means read”?

The terrorists tried to stop us and attacked me and my friends who are here today, on our school bus in 2012, but neither their ideas nor their bullets could win.

We survived. And since that day, our voices have grown louder and louder.

I tell my story, not because it is unique, but because it is not.

It is the story of many girls.

Today, I tell their stories too. I have brought with me some of my sisters from Pakistan, from Nigeria and from Syria, who share this story. My brave sisters Shazia and Kainat who were also shot that day on our school bus. But they have not stopped learning. And my brave sister Kainat Soomro who went through severe abuse and extreme violence, even her brother was killed, but she did not succumb.

Also my sisters here, whom I have met during my Malala Fund campaign. My 16-year-old courageous sister, Mezon from Syria, who now lives in Jordan as refugee and goes from tent to tent encouraging girls and boys to learn. And my sister Amina, from the North of Nigeria, where Boko Haram threatens, and stops girls and even kidnaps girls, just for wanting to go to school.

Though I appear as one girl, though I appear as one girl, one person, who is 5 foot 2 inches tall, if you include my high heels. (It means I am 5 foot only) I am not a lone voice, I am not a lone voice, I am many.

I am Malala. But I am also Shazia.

I am Kainat.

I am Kainat Soomro.

I am Mezon.

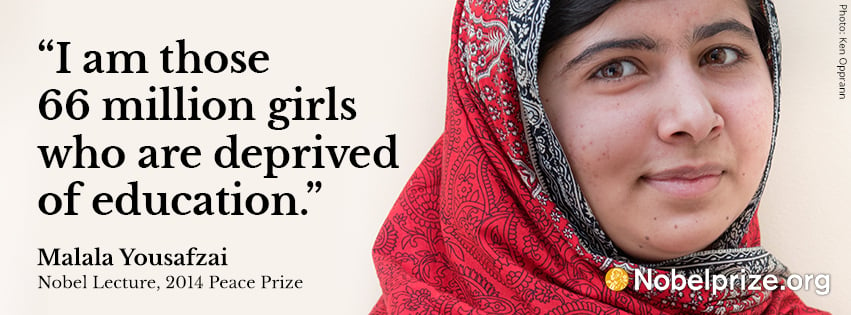

I am Amina. I am those 66 million girls who are deprived of education. And today I am not raising my voice, it is the voice of those 66 million girls.

Sometimes people like to ask me why should girls go to school, why is it important for them. But I think the more important question is why shouldn’t they, why shouldn’t they have this right to go to school.

Dear sisters and brothers, today, in half of the world, we see rapid progress and development. However, there are many countries where millions still suffer from the very old problems of war, poverty, and injustice.

We still see conflicts in which innocent people lose their lives and children become orphans. We see many people becoming refugees in Syria, Gaza and Iraq. In Afghanistan, we see families being killed in suicide attacks and bomb blasts.

Many children in Africa do not have access to education because of poverty. And as I said, we still see, we still see girls who have no freedom to go to school in the north of Nigeria.

Many children in countries like Pakistan and India, as Kailash Satyarthi mentioned, many children, especially in India and Pakistan are deprived of their right to education because of social taboos, or they have been forced into child marriage or into child labour.

One of my very good school friends, the same age as me, who had always been a bold and confident girl, dreamed of becoming a doctor. But her dream remained a dream. At the age of 12, she was forced to get married. And then soon she had a son, she had a child when she herself was still a child – only 14. I know that she could have been a very good doctor.

But she couldn’t … because she was a girl.

Her story is why I dedicate the Nobel Peace Prize money to the Malala Fund, to help give girls quality education, everywhere, anywhere in the world and to raise their voices. The first place this funding will go to is where my heart is, to build schools in Pakistan—especially in my home of Swat and Shangla.

In my own village, there is still no secondary school for girls. And it is my wish and my commitment, and now my challenge to build one so that my friends and my sisters can go there to school and get quality education and to get this opportunity to fulfil their dreams.

This is where I will begin, but it is not where I will stop. I will continue this fight until I see every child, every child in school.

Dear brothers and sisters, great people, who brought change, like Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela, Mother Teresa and Aung San Suu Kyi, once stood here on this stage. I hope the steps that Kailash Satyarthi and I have taken so far and will take on this journey will also bring change – lasting change.

My great hope is that this will be the last time, this will be the last time we must fight for education. Let’s solve this once and for all.

We have already taken many steps. Now it is time to take a leap.

It is not time to tell the world leaders to realise how important education is – they already know it – their own children are in good schools. Now it is time to call them to take action for the rest of the world’s children.

We ask the world leaders to unite and make education their top priority.

Fifteen years ago, the world leaders decided on a set of global goals, the Millennium Development Goals. In the years that have followed, we have seen some progress. The number of children out of school has been halved, as Kailash Satyarthi said. However, the world focused only on primary education, and progress did not reach everyone.

In year 2015, representatives from all around the world will meet in the United Nations to set the next set of goals, the Sustainable Development Goals. This will set the world’s ambition for the next generations.

The world can no longer accept, the world can no longer accept that basic education is enough. Why do leaders accept that for children in developing countries, only basic literacy is sufficient, when their own children do homework in Algebra, Mathematics, Science and Physics?

Leaders must seize this opportunity to guarantee a free, quality, primary and secondary education for every child.

Some will say this is impractical, or too expensive, or too hard. Or maybe even impossible. But it is time the world thinks bigger.

Dear sisters and brothers, the so-called world of adults may understand it, but we children don’t. Why is it that countries which we call strong” are so powerful in creating wars but are so weak in bringing peace? Why is it that giving guns is so easy but giving books is so hard? Why is it, why is it that making tanks is so easy, but building schools is so hard?

We are living in the modern age and we believe that nothing is impossible. We have reached the moon 45 years ago and maybe will soon land on Mars. Then, in this 21st century, we must be able to give every child quality education.

Dear sisters and brothers, dear fellow children, we must work… not wait. Not just the politicians and the world leaders, we all need to contribute. Me. You. We. It is our duty.

Let us become the first generation to decide to be the last , let us become the first generation that decides to be the last that sees empty classrooms, lost childhoods, and wasted potentials.

Let this be the last time that a girl or a boy spends their childhood in a factory.

Let this be the last time that a girl is forced into early child marriage.

Let this be the last time that a child loses life in war.

Let this be the last time that we see a child out of school.

Let this end with us.

Let’s begin this ending … together … today … right here, right now. Let’s begin this ending now.

Thank you so much.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2014

Malala Yousafzai – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, Malala Yousafzai, receiving her Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony at the Oslo City Hall in Norway, 10 December 2014.

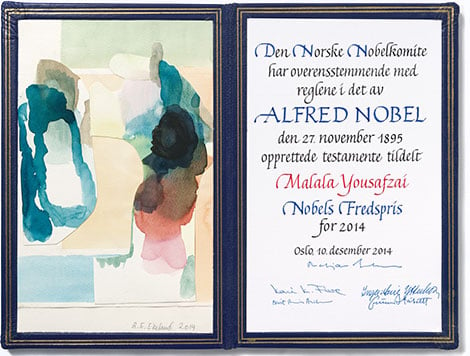

Malala Yousafzai – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2014

Artist: Ruth Elisiv Ekeland

Calligrapher: Inger Magnus

Book binder: Julius Johansen

Photo reproduction: Thomas Widerberg

Dmitry Muratov – Speed read

Dmitry Muratov was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his courageous fight for freedom of expression in Russia.

Full name: Dmitry Andreyevich Muratov

Born: 29 October 1961, Kubyshev, USSR (now Samara, Russia)

Date awarded: 8 October 2021

A fearless defender of freedom of speech

Dmitry Muratov is a Russian journalist and editor-in-chief. He is one of the founders of the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, where he has been editor since 1994. He is known as a fearless critic of the regime in Russia. Dmitry Muratov became involved in journalism as a student in Moscow and worked part-time at a newspaper. In 1987, he became a correspondent for the newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda, where he was quickly promoted to news editor. In 1993, Muratov and about 50 colleagues left Komsomolskaya Pravda to start their own newspaper, Novaya Gazeta. Muratov has defended freedom of expression in Russia for many years, under increasingly demanding conditions. He has won several awards for his work, including the International Prize for Freedom of the Press in 2007.

“Russian journalism is being suppressed right now. We will try to help people who are now recognized as ‘foreign agents’ and who are being attacked and expelled from the country.“

– Dmitry Muratov, The Moscow Times, 8 October 2021

Novaya Gazeta – A powerful channel for revealing injustice

The Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta was founded in 1993. The following year, Dmitry Muratov became its editor. Novaya Gazeta is one of the few independent newspapers in Russia that is openly critical of the ruling elite. The newspaper is published three times a week and features investigative articles on corruption, human rights violations, electoral fraud and misinformation. The employees of Novaya Gazeta are constantly exposed to threats and harassment. Six of the newspaper’s journalists have been killed. Despite this, Dmitry Muratov continues his work of informing the Russian people about blameworthy aspects of Russian society.

Truth for sale

Muratov and Novaya Gazeta cover many stories that are not featured in other Russian media. In addition to investigating topics such as corruption and police violence, the newspaper has also focused on so-called “troll factories”. A troll factory is a kind of media channel that produces fake news to order. These factories operate secretly, and it is often difficult to trace fake news back to them. In recent years, they have been accused of influencing elections in many countries around the world, including Russia and the United States.

| Freedom of the press Freedom of the press means that the press has the right to provide information, and engage in criticism and debate, without censorship or risk of retaliation. |

Persecuted journalists in Russia

The Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index for 2021 ranks Russia at 150th place out of 180. In comparison, Norway is ranked No. 1. Russian journalists work under increasingly difficult conditions and are exposed to violence, threats and killings. Since the year 2000, 26 journalists have been killed. Anna Politkovskaya is one of the most famous. She worked for Novaya Gazeta and wrote revealing articles about the war in Chechnya. She was killed in 2006.

“I hope this prize will help us to protect ourselves against attacks from the authorities. This award is important not just for us, but the whole of the Russian journalism community.“

– Pavel Kanygin, Novaya Gazeta reporter, The Moscow Times, 8 October 2021.

| Freedom of expression The right you have to express your opinion, as long as it is not hateful or discriminatory. You also have the right to receive and provide information. |

| Democracy Greek for government by the people. A form of government in which all adult citizens participate in the governing of the state and everyone is equal under the law. Most democracies are representative governments. Individuals are elected to assemblies that take decisions on behalf of all citizens. |

Freedom of expression awards

Announcing the Nobel Peace Prize for 2021, the Norwegian Nobel Committee emphasised freedom of expression as a prerequisite for democracy and lasting peace. The peace prize has been given to brave critics before. Two of the most famous, Carl von Ossietzky in 1936 (for 1935) and Liu Xiaobo in 2010, also faced strong reactions when they received it. Among other famous peace laureates who had to endure threats and persecution for their outspokenness are Martin Luther King jr (1964), Nelson Mandela (1993) and Malala Yousafzai (2014). Including Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov, 15 journalists and writers have received the Nobel Peace Prize.

“This award is in memory of our slain colleagues. They were brave. We will continue their work.“

– Dmitry Muratov, interview with the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, 8 October 2021.

Learn more

In this interview from September 2023 Dmitry Muratov talks about what the Nobel Peace Prize has meant to him, what inspires him and why freedom of speech is so important.

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.