Heike Kamerlingh Onnes – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1913

Investigations into the properties of substances at low temperatures, which have led, amongst other things, to the preparation of liquid helium

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 723 kB

Heike Kamerlingh Onnes – Banquet speech

Heike Kamerlingh Onnes’ speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1913 (in German)

Königliche Hoheiten, Meine Damen, Meine Herren!

Mit tiefer Rührung spreche ich bei dieser Feier, welcher die Beteiligung des Königlichen Hauses ihren Zauber verleiht, meinen innigst gefühlten Dank aus für die mir heute erwiesene Ehre, deren Bedeutung noch dadurch erhöht wird, dass ich sie aus den Händen Seiner Majestät des Königs empfangen durfte.

Jener Augenblick wird seinen Glanz weiter über mein ganzes Leben ausbreiten, und keine Schwierigkeit wird jetzt mehr so gross sein können, dass ich ihr gegenüber nicht frohen Mutes bliebe.

Für dieses Glück kann man nur in einer Weise danken, das ist die, welche die Nobelpreisträger angewiesen haben, indem sie auch ihr weiteres Leben ganz der Wissenschaft gewidmet haben. Dies nach bestem Vermögen zu tun, ist mein innerstes Bedürfnis.

Wie Selma Lagerlöf in ihrer reizenden Erzählung uns gelehrt hat, soll man, wenn man den Nobelpreis empfangen hat, nach nichts weiter fragen, aber froh sein. Und das kann ich sagen: meine Freude ist unermesslich.

Es trägt dazu bei, dass sie geteilt wird von allen, die im Leydener Laboratorium zusammen gearbeitet haben und arbeiten und die diese Ehrung als einen Triumph für das Laboratorium mit empfinden.

Eine ganz besondere Freude bringt dieser Tag meinem hochverehrten Freunde van der Waals. Wie ich es als ein Glück empfand, ihm mitzuteilen, dass das Helium nach seiner Lehre verflüssigt war, weiss ich, dass dieser Tag ihn mit Freude erfüllt.

Und dann erhöht es mein Glück nicht wenig, dass ganz Holland sich mit mir freut. Ich habe immer daran gearbeitet, dass man in gewissem Sinne von einer holländischen Wissenschaft sprechen darf. Im Falle des Heliums war es geradezu ein leidenschaftliches Verlangen geworden, dasselbe zu verflüssigen auf demselben Fleckchen Erde, wo van Marum das erste Gas verflüssigt hatte. Und ich glaube, dass ich für diese Vaterlandsliebe einen warmen Anklang finde in den Herzen der Schweden, deren Vaterland so weit ausser Verhältnis zu der Zahl der Einwohner in die Weltgeschichte eingegriffen hat.

Die Wissenschaft ist ein internationales Gut, aber in der Pflege derselben haben die Nationen zu wetteifern. In der Zukunft wird die Stellung eines Volkes wohl nur beurteilt werden nach dem, was es in dieser und ähnlicher friedlicher Weise zum Gemeinwohl beiträgt. Das schwedische Volk erfüllt seine Rolle glänzend. Die weitsehende Freigebigkeit seines grossen Sohnes Nobel trägt zur Förderung der Wissenschaft bei in einer Weise, die einzig in der Welt ist. Und zu gleicher Zeit werden von den Forschern Ihres Landes fortwährend Beiträge zur Wissenschaft geliefert, die eine würdige Fortsetzung sind der Arbeiten, durch welche Ångström und Thalén, wenn ich mich jetzt auf die Physik beschränke, die Pflege derselben in ihren schwedischen Heimstätten mit Ruhm gekrönt haben.

Ich bin recht glücklich, zu den schwedischen Physikern in immer engere Beziehung zu kommen. Überhaupt wäre es schön, wenn die Bande zwischen Schweden und Holland wieder engere würden. Wenn Prof. Wrangel die Zeit, wo unser Grotius der Gesandte von Schweden in Paris war, wo Ihr Linneus in Holland arbeitete und die Oxenstjerna’s in Holland studierten, in neuer Weise zurückrufen möchte, stimme ich ihm aus vollem Herzen bei. Für die Physik sind diese Bande schon wieder recht innig geworden. Ich möchte hier in erster Reihe den Dank meines Landes aussprechen für die Nobelpreise, welche holländischen Physikern zuerkannt sind. Und dann möchte ich persönlich des Aufenthaltes Ihres talentvollen Forschers Herrn Dr. Beckman und seiner Frau Gemahlin in Leiden gedenken. Herzlich hoffe ich, dass beide aufs neue und dass auch andere schwedische Forscher die Gastfreundschaft meines Laboratoriums werden annehmen wollen. Und dazu die Gastfreundschaft unseres Hauses. Wir möchten so gerne doch einigermassen die überaus liebenswürdige Weise erwiedern, in welcher uns hier alle Herzen entgegen gekommen sind, und die auch aus den freundlichen Begrüssungsworten des Herrn Präsidenten Nordström spricht. Indem ich herzlichst für dieselben danke, erhebe ich mein Glas zu Ehren der schwedischen Physiker.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Heike Kamerlingh Onnes – Photo gallery

The Cryogenics Laboratory in Leiden, 1919. From left: Paul Ehrenfest, Hendrik Lorentz, 1922 Nobel Laureate in Physics Niels Bohr and 1913 Nobel Laureate in Physics Heike Kamerlingh Onnes.

Photographer unknown Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Heike Kamerlingh Onnes (left) and Johannes Diderik van der Waals (right) in front of the helium-'liquefactor', Leiden 1908.

Photographer unknown Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Heike Kamerlingh Onnes – Nominations

Heike Kamerlingh Onnes – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Heike Kamerlingh Onnes from National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by former Councillor Th. Nordstrom, President of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, on December 10, 1913

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen.

At its meeting on the 11th November the Royal Academy of Sciences decided to award the Nobel Prize for Physics for the year 1913 to Dr. Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, Professor at the University of Leyden “for his investigations on the properties of matter at low temperatures which led, inter alia, to the production of liquid helium”.

As early as 100 years ago research into the behaviour of gases at various pressures and temperatures gave a great impetus to physics. Since this time the study of the connection between the pressure, the volume and the temperature of gases has played a very important part in physics, and particularly in thermodynamics – one of the most important disciplines of modern physics.

In the years 1873 and 1880 Van der Waals presented his famous laws governing gases which, owing to their great importance for thermodynamics, were rewarded by the Royal Academy of Sciences in 1910 with the Nobel Prize for Physics.

The thermodynamic laws of Van der Waals were laid down on atheoretical basis under the assumption that certain properties could be attributed to molecules and molecular forces. In the case of gases the properties of which are changed by pressure and temperature, or in one way or another do not agree with Van der Waals’ hypothesis, deviations from these laws occur.

A systematic experimental study of these deviations and the changes they undergo due to temperature and the molecular structure of the gas must therefore contribute greatly to our knowledge of the properties of the molecules and of the phenomena associated with them.

It was for this research that Kamerlingh Onnes set up his famous laboratory at the beginning of the 1880’s, and in it he designed and improved, with unusual success, the physical apparatus needed for his experiments.

It is impossible to report briefly here on the many important results of this work. They embrace the thermodynamic properties at low temperatures of a series of monatomic and diatomic gases and their mixtures, and have contributed to the development of modern thermodynamics and to an elucidation of those associated phenomena which are so difficult to explain. They have also made very important contributions to our knowledge of the structure of matter and of phenomena related to it.

Whilst important on its own account, this research has gained greater significance because it has led to the attainment of the lowest temperatures so far reached. These lie in the vicinity of so-called absolute zero, the lowest temperature in thermodynamics.

The attainment of low temperatures in general was not possible until we learnt to condense the so-called permanent gases, which, since Faraday’s pioneer work in this field in the middle of the 1820’s, has been one of the most important tasks of thermodynamics.

After Olszewski, Linde, and Hampson had prepared liquid oxygen and air in a variety of ways, and after Dewar, having overcome great experimental difficulties, had succeeded in condensing hydrogen, all temperatures down to -259°C, i.e. all temperatures down to 14° from absolute zero, could be attained.

At these low temperatures all known gases can easily be condensed, except for helium, which was discovered in the atmosphere in the year 1895.

Thus, by condensing this it would be possible to reach still lower temperatures. After both Olszewski and Dewar, Travers, and Jacquerod had tried in vain to prepare liquid helium, using a variety of met hods it was generally assumed that it was impossible.

The question was solved in 1908, however, by Kamerlingh Onnes, who then prepared liquid helium for the first time.

I should have to cover too much ground if I were to report here on the experimental equipment with which Kamerlingh Onnes was at last successful in liquefying helium, and on the enormous experimental difficulties which had to be overcome. I would only mention here that the liquefaction of helium represented a continuation of the long series of investigations into the properties of gases and liquids at low temperatures which Kamerlingh Onnes has carried out in so praiseworthy a manner. These investigations finally led to the determination of the so-called isotherms of helium and the knowledge gained here was the first step towards the liquefaction of helium. Kamerlingh Onnes has constructed cold baths with liquid helium which permit research to be done into the properties of substances at temperatures which lie between 4,3° and 1,15° from absolute zero.

The attainment of these low temperatures is of the greatest importance to physics research, for at these temperatures both the properties of the substances and also the course followed by physical phenomena, are generally quite different from those at our normal and higher temperatures, and a knowledge of these changes is of fundamental importance in answering many of the questions of modern physics.

Let me mention one of these particularly here.

Various principles borrowed from gas thermodynamics have been transferred to the so-called theory of electrons, which is the guiding principle in physics in explaining all electrical, magnetic, optical, and many heat phenomena.

The laws which have been arrived at in this way also seem to be confirmed by measurements at our normal and higher temperatures. That the situation is at very low temperatures not the same, however, has, amongst other things, been shown by Kamerlingh Onnes’ experiments on resistance to electrical conduction at helium temperatures and by the determinations which Nernst and his students have carried out in relation to specific heat at liquid temperatures.

It has become more and more clear that a change in the whole theory of electrons is necessary. Theoretical work in this direction has already been begun by a number of research workers, particularly by Planck and Einstein.

In the meantime new supports had to be created for these investigations. These could only be obtained by a continued experimental study of the properties of substances at low temperatures, particularly at helium temperatures, which are the most suitable for throwing light upon phenomena in the world of electrons. Kamerlingh Onnes’ merit lies in the fact that he has created these possibilities and at the same time opened up a field of the greatest consequence and significance to physical science.

Owing to the great importance which Kamerlingh Onnes’ work has been seen to have for research in physics, the Royal Academy of Sciences has found ample grounds for bestowing upon him the Nobel Prize for Physics for the year 1913.

The Nobel Prize in Physics 1913

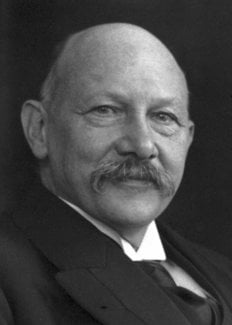

Heike Kamerlingh Onnes – Biographical

Heike Kamerlingh Onnes was born on September 21, 1853, at Groningen, The Netherlands. His father, Harm Kamerlingh Onnes, was the owner of a brickworks near Groningen; his mother was Anna Gerdina Coers of Arnhem, the daughter of an architect.

After spending the allotted time at the “Hoogere Burgerschool” in his native town (secondary school without classical languages), the director of which was the later Professor of Chemistry at Leyden J.M. van Bemmelen, he received supplementary teaching in Greek and Latin. In 1870 he entered the University of Groningen, obtained his “candidaats” degree (approx. B.Sc.) the following year, and then went to Heidelberg as a student of Bunsen and Kirchhoff from October 1871 until April 1873. Thereafter he returned to Groningen, where he passed his “doctoraal” examination (approx. M.Sc.) in 1878 and obtained the doctor’s degree in 1879 with a remarkable thesis Nieuwe bewijzen voor de aswenteling der aarde (New proofs of the rotation of the earth).

Meanwhile in 1878 he had become assistant at the Polytechnicum at Delft, working under Bosscha, in whose place he also lectured in 1881 and 1882, the year in which he was appointed Professor of Experimental Physics and Meteorology at Leyden University, in succession to P.L. Rijke.

Kamerlingh Onnes’ talents for solving scientific problems was already apparent in 1871, when at the age of 18 he was awarded a Gold Medal for a competition sponsored by the Natural Sciences Faculty of the University of Utrecht, followed the next year by a Silver Medal for a similar event at the University of Groningen. When working with Kirchhoff he also won the “Seminarpreis”, entitling him to occupy one of the two existing assistantships under Kirchhoff.

In his doctor’s thesis theoretical as well as experimental proof was given that Foucault’s well-known pendulum experiment should be considered as a special case of a large group of phenomena which in a much simpler fashion can be used to prove the rotational movement of the earth. In 1881 he published a paper Algemeene theorie der vloeistoffen (General theory of liquids), which dealt with the kinetic theory of the liquid state, approaching Van der Waals’ law of corresponding states from a mechanistic point of view. This work can be considered as the beginning of his life-long investigations into the properties of matter at low temperatures. In his inaugural address De beteekenis van het quantitatief onderzoek in de natnurkunde (The importance of quantitative research in physics) he arrived at his well-known motto “Door meten tot weten” (Knowledge through measurement), an appreciation of the value of measurements which concerned him throughout his scientific career.

After his appointment to the Physics Chair at Leyden, Kamerlingh Onnes reorganized the Physical Laboratory (now known as the Kamerlingh Onnes Laboratory) in a way to suit his own programme. His researches were mainly based on the theories of his two great compatriots J.D. van der Waals and H.A. Lorentz. In particular he had in mind the establishment of a cryogenic laboratory which would enable him to verify Van der Waals’ law of corresponding states over a large range of temperatures. His efforts to reach extremely low temperatures culminated in the liquefaction of helium in 1908. Bringing the temperature of the helium down to 0,9°K, he reached the nearest approach to absolute zero then achieved, thus justifying the saying that the coldest spot on earth was situated at Leyden. It was on account of these low-temperature studies that he was awarded the Nobel Prize. Later, his pupils W.H. Keesom and W.J. de Haas ( Lorentz’ son-in-law) conducted experiments in the same laboratory which led them still closer to absolute zero.

Other investigations in his laboratory which gradually gained in importance and international fame, included thermodynamics, the radioactivity law, and observations on optical, magnetic and electrical phenomena, such as the study of fluorescence and phosphorescence, the magnetic rotation of the polarization plane, absorption spectra of crystals in the magnetic field; also the Hall effect, dielectric constants, and especially the resistance of metals. A momentous discovery (1911) was that of the superconductivity of pure metals such as mercury, tin and lead at very low temperatures, and following from this the observation of persisting currents.

The results of Kamerlingh Onnes’ investigations were published in the Proceedings of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Amsterdam and also in the Communications from the Physical Laboratory at Leyden. Many foreign scientists came to Leyden to work in his laboratory for shorter or longer periods. The laboratory gained additional fame throughout the world through the training school for instrument-makers and glass-blowers housed in it, founded by Kamerlingh Onnes in 1901.

At the early age of 30, Kamerlingh Onnes was appointed a member of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Amsterdam. He was one of the founders of the Association (now Institut) International du Froid. He was a Commander in the Order of the Netherlands Lion, the Order of Orange-Nassau of the Netherlands, the Order of St. Olaf of Norway, and the Order of Polonia Restituta of Poland. He held an honorary doctorate of the University of Berlin, and was awarded the Matteucci Medal, the Rumford Medal, the Baumgarten Preis and the Franklin Medal. He was Member of the Society of Friends of Science in Moscow, and of the Academies of Sciences in Copenhagen, Uppsala, Turin, Vienna, Göttingen and Halle; Foreign Associate of the Académie des Sciences of Paris; Foreign Member of the Accademia dei Lincei of Rome and the Royal Society of London; and Honorary Member of the Physical Society of Stockholm, the Société Helvétique des Sciences Naturelles, the Royal Institution of London, the Sociedad Española da Física y Qumica of Madrid, and the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia.

Outside his scientific work, Kamerlingh Onnes’ favourite recreations were his family life and helpfulness to those who needed it. Although his work was his hobby, he was far from being a pompous scholar. A man of great personal charm and philanthropic humanity, he was very active during and after the First World War in smoothing out political differences between scientists and in succouring starving children in countries suffering from food shortage. In 1887 he married Maria Adriana Wilhelmina Elisabeth Bijleveld, who was a great help to him in these activities and who created a home widely known for its hospitality. They had one son, Albert, who became a high-ranking civil servant at The Hague.

Kamerlingh Onnes’ health had always been somewhat delicate, and, after a short illness, he died at Leyden on February 21, 1926.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.