Nobel Prize in Physics 2018

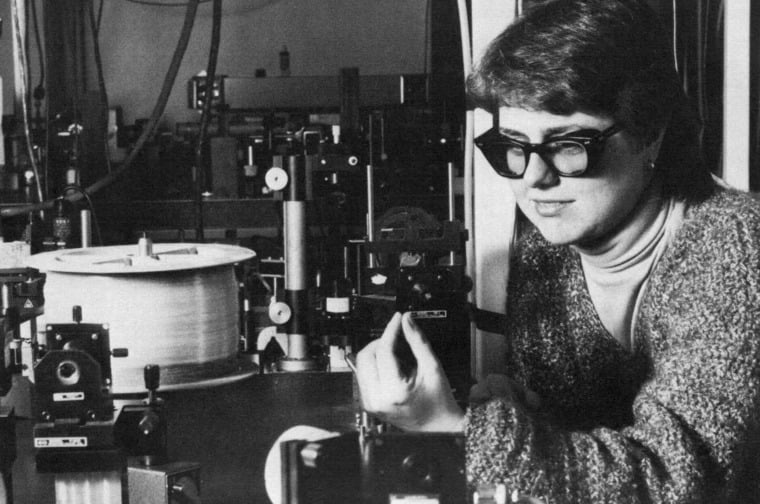

Donna Strickland thinks lasers are cool. With enthusiasm for the field and “very, very hard” work, she found a way to create high-intensity laser pulses. This technique, chirped pulse amplification or CPA, was described in Strickland’s very first scientific paper, and it led to her 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics. More important, it began a long career in which, as she has put it, “I get to play with high-intensity lasers.”

Donna Strickland was born in 1959 in Guelph, in the Canadian province of Ontario. Her mother was an English teacher and her father an electrical engineer. As a high school student, she excelled at math and physics – and only those, she says. “Some people are good at a lot of things. I don’t know how they choose what to do.”

“Do what you love and what you think you are good at.”

Donna Strickland

She enrolled in McMaster University’s engineering physics program, which was advertising its courses on lasers. “Now doesn’t that sound cool,” she thought to herself. “I just got to do that.”

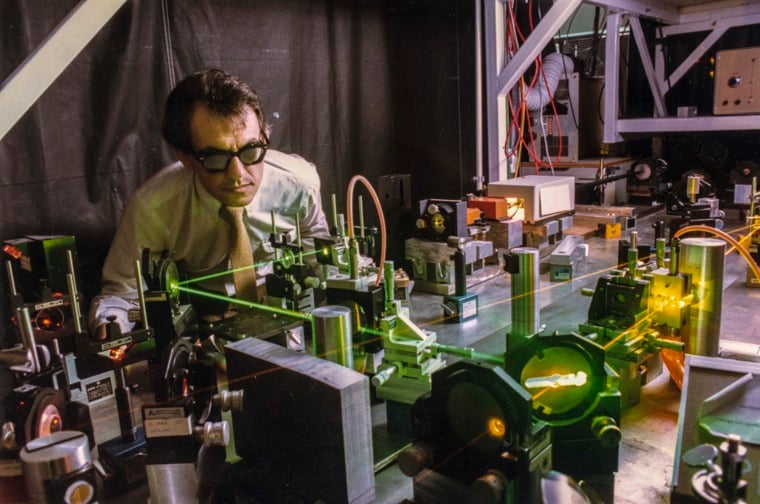

In 1981, Strickland graduated from McMaster University with a bachelor of engineering degree in physics. She was one of three women in a class of 25. At age 22, pursuing her PhD at the University of Rochester, she joined the laser lab of French physicist Gérard Mourou. Mourou was experimenting with higher intensity laser pulses at the time, looking for ways to increase intensity without ripping apart the laser. His hypothesis was that spacing out and augmenting the pulses before bringing them back together would result in higher-intensity laser pulses.

As his doctoral student, Strickland was assigned, as she put it, “to take Gérard’s beautiful idea and make it a reality.” Strickland claims, “It is the one time in my life that I worked very, very hard!” She and her friends called themselves “laser jocks,” because they had to be good with their hands to deal with the finicky instruments of the time.

The team was eventually able to activate and prove Mourou’s hypothesis.

“It is truly an amazing feeling when you know that you have built something that no one else ever has – and it actually works.”

Donna Strickland

They named the technique chirped pulse amplification (CPA). It’s now used in corrective eye surgery, industrial machining and medical imaging, and it’s essential to most high-powered laser facilities.

1 (of 2) A laser rod donated by Donna Strickland to the Nobel Prize Museum.

Photo: © Nobel Prize Museum. Photo: Karl Anderson

2 (of 2) Images of stretched and compressed pulses, from Strickland's 1985 paper on Chirped Pulse Amplification (CPA.)

Photo: Elsevier / Optics Communications

After earning her PhD in optics in 1989, it took eight years for Strickland to find a full-time university position.

She attributes this in part to the “two-body problem,” a serious obstacle for married academics – particularly women. When two academics marry, they often have trouble finding positions for them both, due to the relative lack of university jobs. Historically, it’s the woman’s career that is put on hold for the sake of her husband’s, as it was for Strickland.

In 1991 she married physicist Doug Dykaar, who had a permanent position at Bell Labs in New Jersey. After a year working as a research associate under Paul Corkum at the National Research Council, at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, Strickland also moved to New Jersey, joining the technical staff of Advanced Technology Center for Photonics and Opto-electronic Materials at Princeton.

However, in 1997, the tables turned: Strickland was hired by the University of Waterloo, not far from where she grew up, and Dykaar relocated to work in industry nearby.

She has taught and researched at Waterloo for the past two decades, now as the associate chair of the physics department and head of the university’s Ultrafast Laser Group.

But she was still just an associate professor when she was awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics. It wasn’t the university’s fault that she hadn’t been made a full professor, she has said: she simply never applied. “I’m just a lazy person. I do what I want to do and that wasn’t worth doing.”

Whatever her title, Strickland helped revolutionise laser physics, as well as shed light on a lack of women in her field.

“We need to celebrate women physicists because they’re out there… I’m honoured to be one of those women.”

Donna Strickland

Her own career sets an example for other women physicists, and she has worked to bring more women into her department at Waterloo. Her daughter, Hannah, is currently doing a graduate course in astrophysics. Still, Strickland told a reporter from the Guardian, “I don’t see myself as a woman in science. I see myself as a scientist.”