Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1935

The radiochemist Irène Joliot-Curie was a battlefield radiologist, activist, politician, and daughter of two of the most famous scientists in the world: Marie and Pierre Curie. Along with her husband, Frédéric, she discovered the first-ever artificially created radioactive atoms, paving the way for innumerable medical advances, especially in the fight against cancer.

Photograph showing a group of alpha-rays from polonium from Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot.

Photo: Iréne Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot. Enquiries to Science Museum, London

Photograph showing a pair of electrons produced in a lead screen by gamma-rays of beryllium bombarded by alpha-rays from polonium, together with a proton projected by a neutron (from Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot).

Photo: Iréne Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot. Enquiries to Science Museum, London

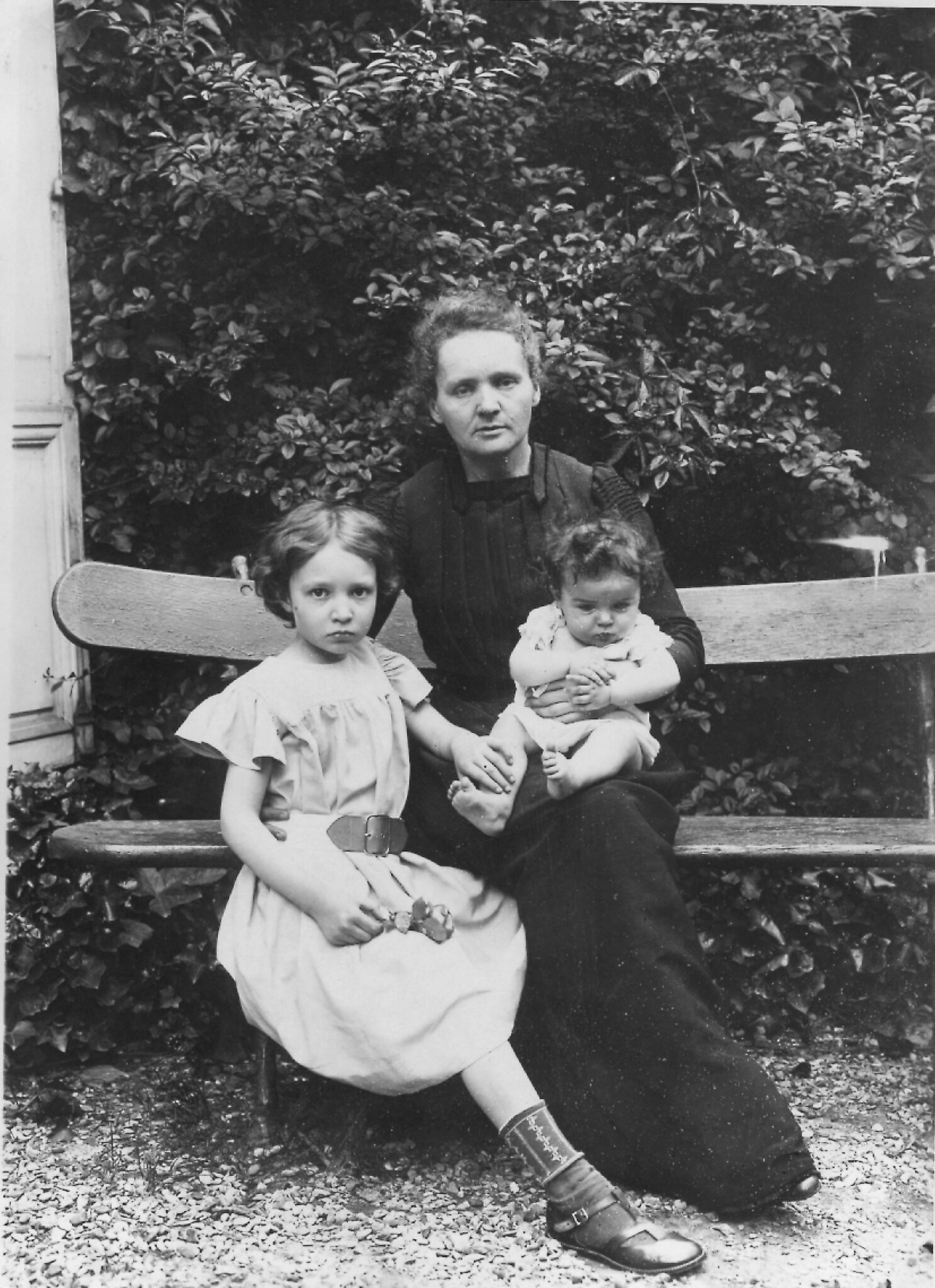

Irène Joliot-Curie was born in Paris in 1897, six years before her parents were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. Early on, they were largely absent, working long hours to isolate radioactive elements. So the young Joliot-Curie was raised by her paternal grandfather, Eugene, a retired doctor who taught her to love nature, poetry, and radical politics.

Her education was sometimes unusual. When she was a young teenager, Joliot-Curie attended a cooperative “school” organised by her mother, in which six professors taught each other’s children in their subjects of expertise, from physics and mathematics to German and art.

Fame struck the Curie family in 1903, followed soon after by tragedy. In 1906, when she was eight years old, Pierre Curie was killed in an accident. Marie Curie began then to spend more time with her daughters (Eve, Irène’s sister, had been born just 16 months before Pierre’s death), and over the years Joliot-Curie took the place of her father as a supporter and a colleague of her mother’s.

During World War I Joliot-Curie learned first-hand that science could save lives. She soon found herself assisting her mother, whose mission was to bring the power of the X-ray to help field surgeons find shrapnel in wounded soldiers.

Marie Curie and Irène Joliot-Curie at the Radium Institute, 1922.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

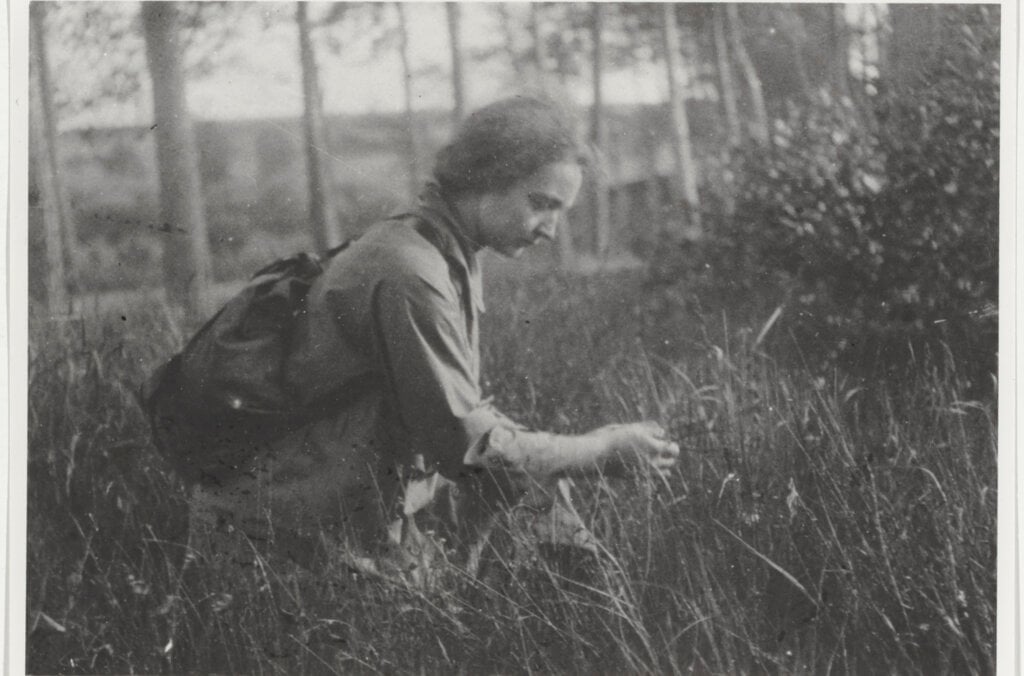

Irène Joliot-Curie at the Radium Institute, 1923.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

Irène Curie and her mother Marie Curie at the Hoogstade Hospital in Belgium, 1915. Radiographic equipment is installed.

© Association Curie Joliot-Curie. Photographer unknown

At age 18, Joliot-Curie was running radiology units in mobile field hospitals, teaching nurses to run X-ray machines, and operating them herself on the Belgian front.

Irène Joliot-Curie climbing down from a "radiological car", 1916.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

Irène Curie, nurse for the Red Cross, in front of her tent at Hoogstade in Belgium, 1915.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

After the war, while working toward her doctorate, Joliot-Curie became her mother’s assistant at the Radium Institute, where her mother asked her to train fellow researcher, Frédéric Joliot. As she taught this chemical engineer about the various methods of their radiochemical lab, she found in Joliot a partner in work who could also be a partner in life. The two young scientists married in 1926, and by 1928 were signing all their research jointly.

Irène Joliot-Curie in the chemistry room of the Curie Laboratory, Radium Institute, March 1922.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot at work in their laboratory, 1938.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

From left to right: Marie Curie, Irène Joliot-Curie, the Curie-Joliot children, Frédéric Joliot, and Madame Joliot.

Photo: Société Française de Physique, Paris

In the early 1930s, the Joliot-Curies twice came close to making significant discoveries, but misinterpreted the results of their experiments – experiments that identified both the positron and the neutron, if only they had realised it.

“Without the love of research, mere knowledge and intelligence cannot make a scientist.”

Irène Joliot-Curie

At last, in 1934, they made the discovery that would alter the course of radiation research and secure their place in the history of science. After bombarding aluminium foil with alpha-particles (helium nuclei), they noticed that the aluminium continued to emit positrons even after the bombardment of alpha-particles had stopped. They deduced that alpha-particle bombardment had converted stable aluminium atoms into radioactive atoms. In other words, they had manufactured radioactive atoms.

Irène Curie at a radiology unit in Amiens, 1916.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie

Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot in 1934

Photo: Société Française de Physique

The ability to artificially create radioactive atoms changed the course of modern physics.

Before, the only way for scientists to obtain radioactive elements was to extract them from their natural ores, an extremely difficult and costly process. Now that they could be made in a laboratory, there was an explosion of research into radioisotopes and the practical applications of radiochemistry, especially in medicine.

Radioisotopes quickly became – and remain – invaluable tools in biomedical research and in cancer treatment.

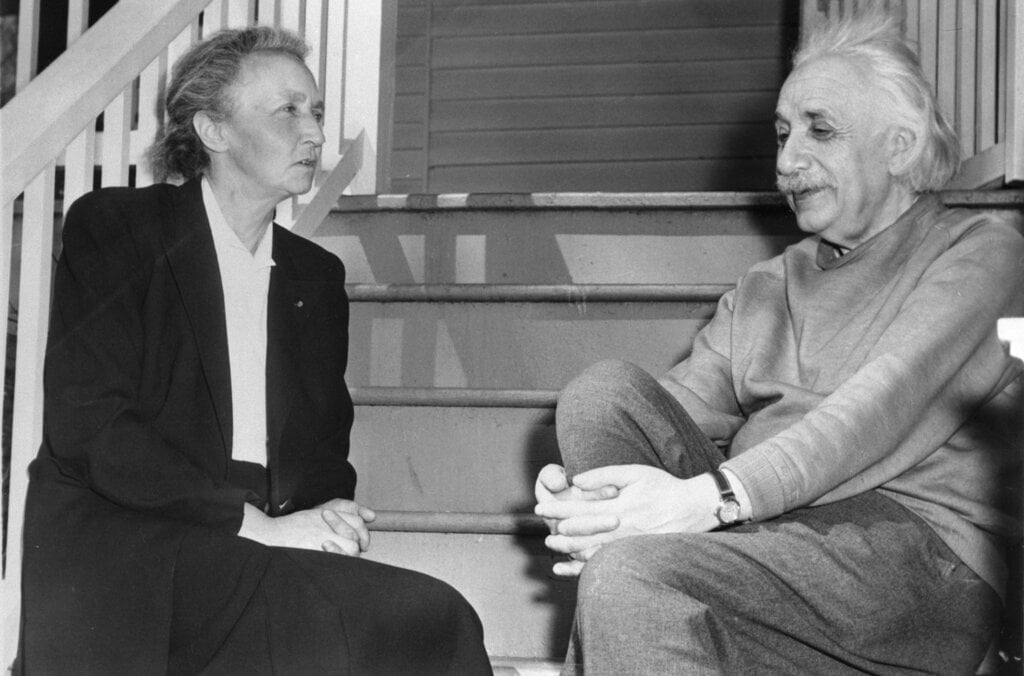

For discovering that radioactive atoms could be created artificially, the Joliot-Curies received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935. Joliot-Curie next helped conduct research into radium nuclei that led a separate group of German physicists to the discovery of nuclear fission, the splitting of the nucleus itself, and the vast amounts of energy emitted as a result. In 1946, she became director of the Radium Institute.

Photo: © Association Curie Joliot-Curie. Photographer unknown

After receiving the Nobel Prize, Joliot-Curie also turned her attention to her children – Hélène and Pierre – and to politics. Years before women could vote in France, she became the Undersecretary of State for Science, advocating for state funding of scientific research.

A member of the Comité National de l’Union des Femmes Françaises and of the World Peace Council she spoke against fascism and Nazism and in favour of women’s education. In 1939, fearful of how the military might use her research in nuclear fission, she and her husband locked their documentation in a vault.

Radioactivity can save lives but it can also kill. As her mother did before her, and her husband would just two years after, Joliot-Curie died of leukaemia caused by extensive exposure to radiation in 1956. She was 58 years old, still researching, still running the Institute, and still attending international conferences for peace and women’s rights – a citizen-scientist to the end.