Nobel Prize in Physics 1963

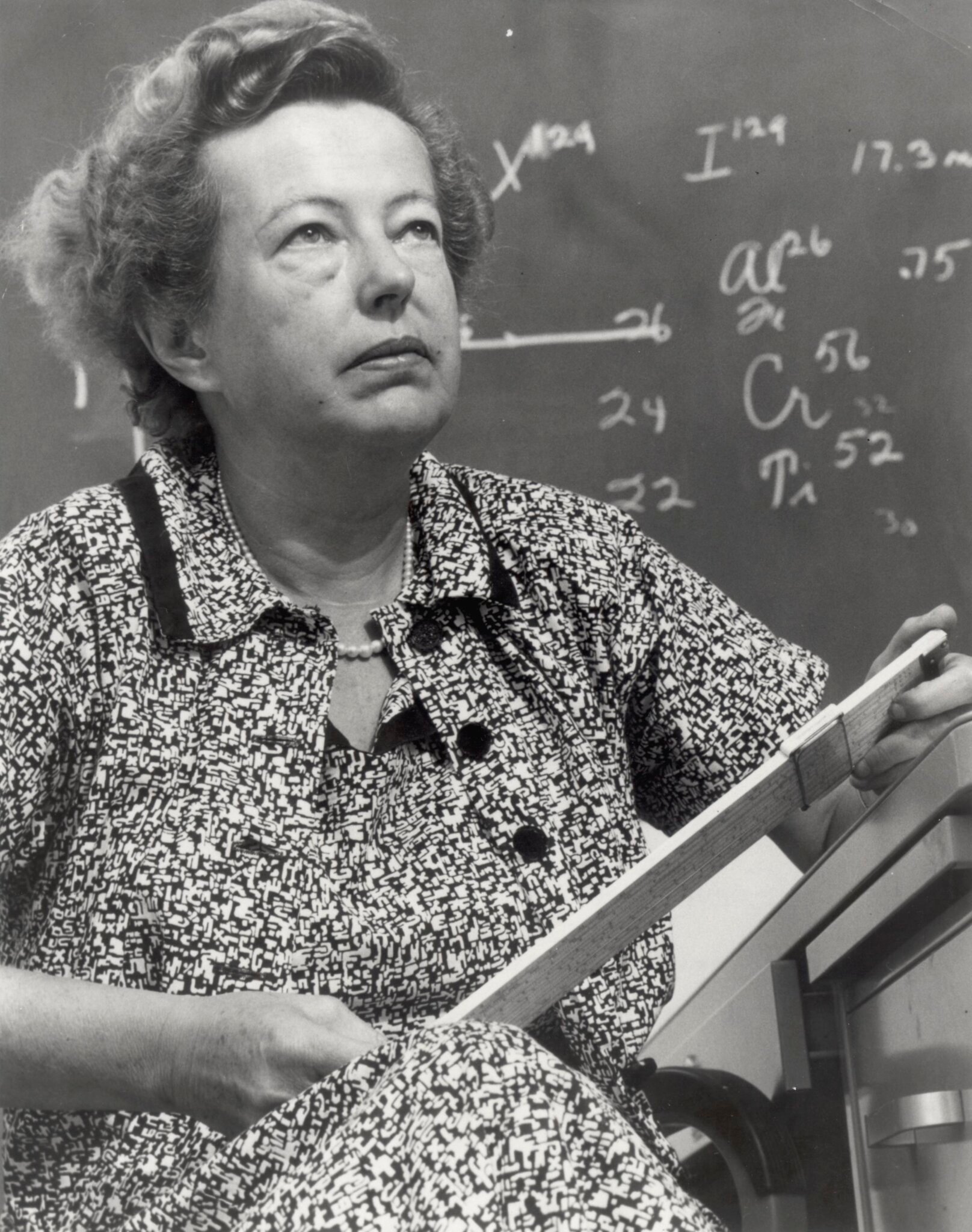

For most of her career, Maria Goeppert Mayer worked “just for the fun of doing physics,” without pay or status or a tenured position. She was 58 before she became a full professor. And yet she made major contributions to the growing understanding of nuclear physics, including the revelatory nuclear shell model.

As the only child of a sixth-generation academic, Maria Goeppert Mayer was expected to go to university. “My father said, ‘Don’t grow up to be a woman,’ and what he meant by that was, a housewife.”

But in Göttingen, Germany, in the early 1900s, girls didn’t have many educational options. The one school for girls closed a year before Goeppert Mayer was due to graduate. She took the university entrance exam anyway – and passed – along with just four other girls.

When she enrolled in university in 1924, fewer than one in ten German university students was female.

1 (of 2) Maria Goeppert Mayer, Hedi Born, Max Born, Maria Stein, Gustav Born (center front), Irene Born (reclining). Max Born was Maria Goeppert Mayer's doctoral supervisor at the University of Göttingen in Germany.

Photo: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Maria Stein Collection

2 (of 2) Victor Weisskopf, Maria Goeppert Mayer and Max Born, ca. 1930. Born was Goeppert Mayer's doctoral supervisor at the University of Göttingen in Germany.

Photo: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection. Gift of Jost Lemmerich

The University of Göttingen was a centre of modern physics in the 1920s, with faculty such as Max Born and Werner Heisenberg. Robert Oppenheimer and Enrico Fermi were among the students. Goeppert Mayer had intended to study math, but could not resist the lure of physics. She was awarded her doctorate in 1930.

“Mathematics began to seem too much like puzzle solving. Physics is puzzle solving, too, but of puzzles created by nature, not by the mind of man.”

Maria Goeppert Mayer

Full-time employment as a professor, however, proved more elusive than the Nobel Prize. For three decades, Goeppert Mayer followed her husband, the chemist Joseph Mayer, to Johns Hopkins University, then Columbia University, then the University of Chicago. At each university, she worked as a “fellow” or “research associate” or “volunteer associate professor,” known for her chain-smoking, chalk-waving intensity. But because of anti-nepotism rules, none of these universities gave her a salary or a full-time position.

1 (of 2) From left: Maria Goeppert Mayer, Joseph Mayer, Robert Atkinson, Paul Ehrenfest and Lars Onsager at University of Michigan Summer School, 1930.

Photo: Samuel Goudsmit, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Goudsmit Collection

2 (of 2) From left: Robert Atkinson, Enrico Fermi, and Maria Goeppert Mayer in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Photo: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Goudsmit Collection

The urgency of World War II prompted the US government to treat Goeppert Mayer’s expertise with more respect than its major universities did. She was “volunteering” at Columbia in the late 1930s and early 1940s when the university was conducting top-secret research to enrich uranium for an atomic bomb. After Pearl Harbor, Goeppert Mayer took over Enrico Fermi’s classes, for which she was not paid.

1 (of 2) Maria Goeppert Mayer (second from right) with faculty in the dining hall, 1943 Sarah Lawrence College Yearbook. Sarah Lawrence was the first institution to give Goeppert Mayer a salaried position.

Photo: Courtesy Sarah Lawrence College Archives

2 (of 2) A letter requesting that Maria Goeppert Mayer be relieved of her duties to help with an important project for national security: the Manhattan Project.

Photo: Courtesy of the Sarah Lawrence College Archives

But she also helped on bomb research, for which she was paid – by the US government. She also worked briefly with Edward Teller on the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, where they were developing the hydrogen bomb.

Goeppert Mayer was torn when it came to her work on the Manhattan Project. She was vehemently anti-Hitler, but aware that the weapon she was helping to create might be used on German friends and family. She later expressed relief that her part of the project failed.

“We found nothing, and we were lucky... we escaped the searing guilt felt to this day by those responsible for the bomb.”

Maria Goeppert Mayer

After the war, while at yet another unpaid position at the University of Chicago, Goeppert Mayer received an offer of part-time work at Argonne National Laboratory, a centre for nuclear physics. “But I don’t know anything about nuclear physics,” she remembers protesting. Two years later, Goeppert Mayer, then in her early 40s, developed an explanation of atomic nuclei structure.

Investigating the peculiar stability of certain isotopes, she found that if a nucleus possessed a “magic” number of protons or neutrons – 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, or 126 – it tended not to decay, and was more abundant than existing models could explain. But why were these elements more stable?

In 1949, inspired by a question from Enrico Fermi, she proposed that inside the nucleus, protons and neutrons are arranged in a series of nucleon layers, like the layers of an onion, with neutrons and protons rotating around their axes (spinning) and the centre of the nucleus (orbiting) at each level.

When the spin and orbital motions are aligned, the energy of the particle shifts down. However, when they are in opposition, the particle’s energy shifts up. The “magic numbers” correspond to the largest gaps in energy between shifted energy levels, delineating where these nucleon layers, or shells, begin and end. In other words, the nuclear shell model.

1 (of 2) The interior of the Goeppert house in Göttingen, Germany.

Photo: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives. Gift of Maria Stein

2 (of 2) (Left to right): Joseph Mayer, Maria Goeppert Mayer and Max Born at Born's home in Bad Pyrmont, West Germany, September 1964.

Photo: Fotofrost, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Born Collection

“It was like a jigsaw puzzle … I felt that if I had only one more piece of the puzzle, everything would fall into place. I found the piece, and everything became clear.”

Maria Goeppert Mayer

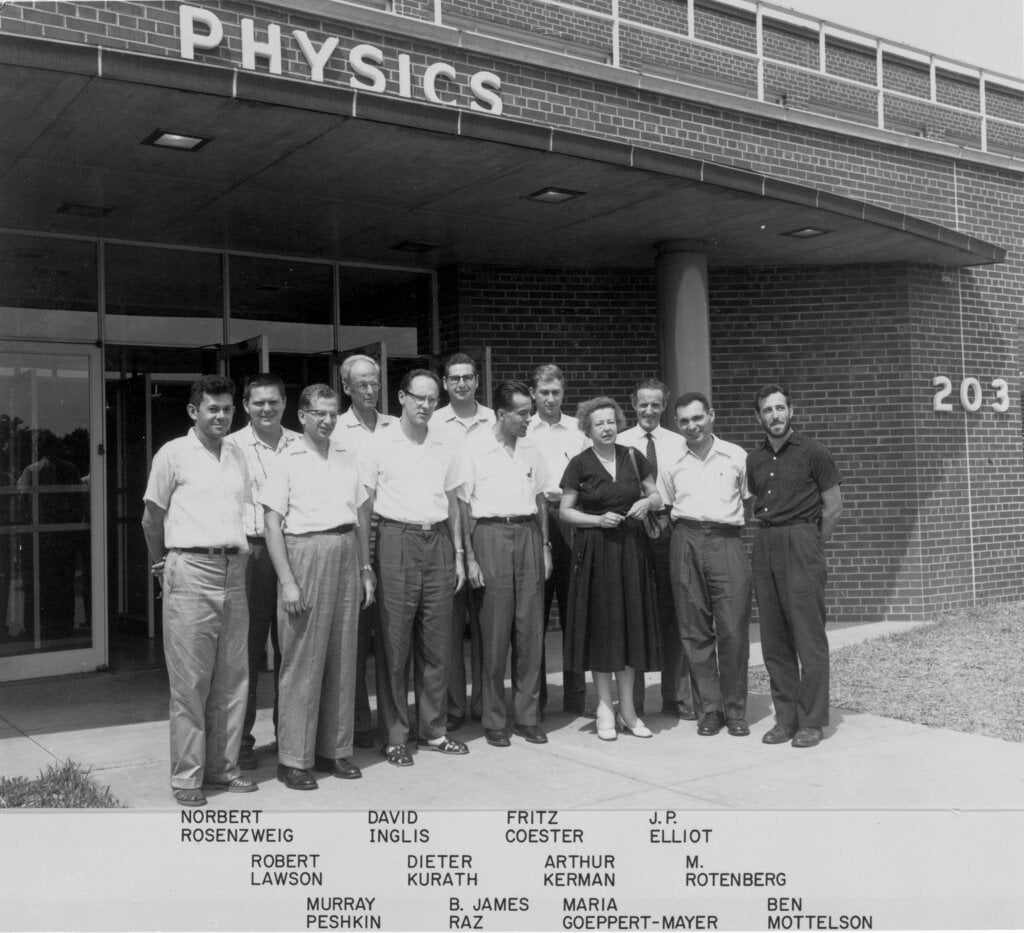

After publishing her theory, Goeppert Mayer found that Hans Jensen and his colleagues had simultaneously made the same discovery. She and Jensen published a book together in 1955, and together they were awarded the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physics.

1 (of 2) Maria Goeppert Mayer among fellow members of the University of Chicago Research Institutes at a New Years' Eve party ca. 1960.

Photo: Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

2 (of 2) King Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden is escorting Maria Goeppert Mayer to the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 1963.

Source: Smithsonian Institution Archives. Photographer unknown

By that point she was, finally, a full professor. The University of California, San Diego, hired Goeppert Mayer in 1960, more than a decade after discovering the nuclear shell model, and 30 years after beginning her career as a scientist.