Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2014

Neuroscientist May-Britt Moser persisted in a decades-long quest to understand how the brain worked at a cellular level. She persevered through a series of challenges – from a reluctant PhD advisor to the birth of two daughters – with a stubborn sense of purpose. Together with her then-husband, Edvard, she learned how the brain perceives where the body is positioned and discovered the cellular basis of cognitive function.

May-Britt Moser was born in 1963. She grew up on a small sheep farm on a remote Norwegian island, the youngest of five children. Her father was a carpenter, while her mother cared for the children and the farm. But Moser’s mother had once longed to enter the medical field herself, and she encouraged Moser to avoid the life of a housewife by studying hard in school. She also told her stories in which the heroes used their intelligence to overcome humble beginnings. “I had this idea that I could do anything,” recalled Moser.

“I was not always the best student with the highest grades, but my teachers saw something in me and tried to encourage me.”

May-Britt Moser

At the University of Oslo in the early 80s, Moser was at first unsure what she wanted to study. Her future became clearer in the company of another young student, Edvard Moser. Together they decided they would study psychology. “We simply burned with eagerness to understand the brain,” said Moser. Their friendship and shared intellectual passion blossomed into a romantic and professional partnership that lasted for decades. They married in 1985.

1 (of 3) May-Britt Moser and Edvard Moser on a tributary of the Amazon in Ecuador, 1986.

Photo: © The Nobel Foundation.

2 (of 3) May-Britt and Edvard Moser in 1997, a year after they were hired by the University of Trondheim and started their lab there.

Photo: NTNU, Gemini magazine

3 (of 3) May-Britt Moser (top left) was one of the students that participated in Per Andersen's Grand Slam, where six students defended their dissertations during the same week, 1995.

Photo: Courtesy Edvard Moser

Their first lab work, on hyperactivity in rats, taught them behavioural theory and experiment design. But they wanted to go inside the brain. They implored neurophysiologist Per Andersen to take them on, even though they were psychology students. Swayed by Moser’s determination, he sent the students on a quest: he would accept them if they built a water maze lab from scratch. Together, they did, and with Andersen’s guidance they studied the hippocampi of rats navigating their maze.

1 (of 2) May-Britt Moser's daughter Isabel reads the journal 'Hippocampus' with great interest. The Mosers frequently brought their daughters to work with them.

Photo: Private/Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience

2 (of 2) May-Britt Moser with her daughters, Isabel and Ailin, 1995.

Photo: © Nobel Prize Outreach

While earning their PhDs, the Mosers had two children, Isabel in 1991 and Ailin in 1995. But their work continued unabated. “Nothing could stop us,” said Moser. The lab rats became their daughters’ pets.

“I just assumed I could do things, like take my children to scientific meetings and breast-feed them in public, or bring them to the lab.”

May-Britt Moser

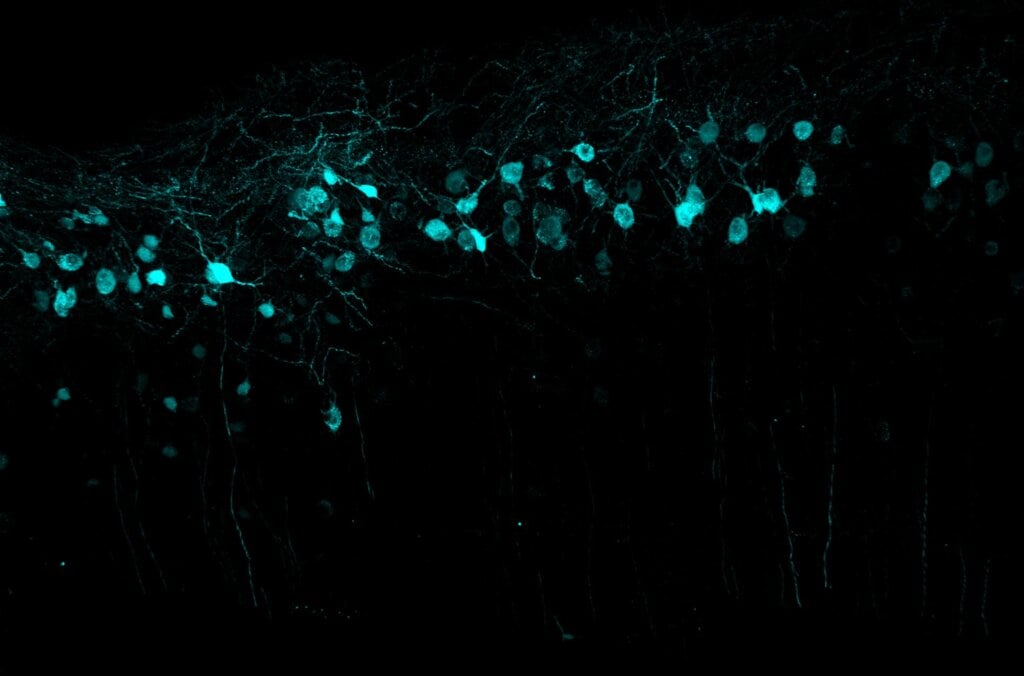

The Mosers received their PhDs in neurophysiology in 1995, and after postdoctoral training in Edinburgh, they went to University College London to work with neuroscientist John O’Keefe. In the 1970s, O’Keefe had discovered that certain neurons in a rat’s hippocampus fired when the rat was at certain places in a room. O’Keefe concluded that these “place cells” actually formed a map of the room.

In what Moser described as “one of the most learning-rich periods in our lives,” O’Keefe taught the visiting Mosers how to record the signals coming from individual cells.

After only a few months in London, though, the Mosers were offered assistant professor positions and a laboratory at the University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. They moved to Trondheim in 1996 and started trying to find the origin of O’Keefe’s place-cell signal. They placed electrodes in the hippocampus of a rat that fed into a computer, mapping onscreen the exact spot where the rat was when each neuron fired. This way they could watch the rat brain at work.

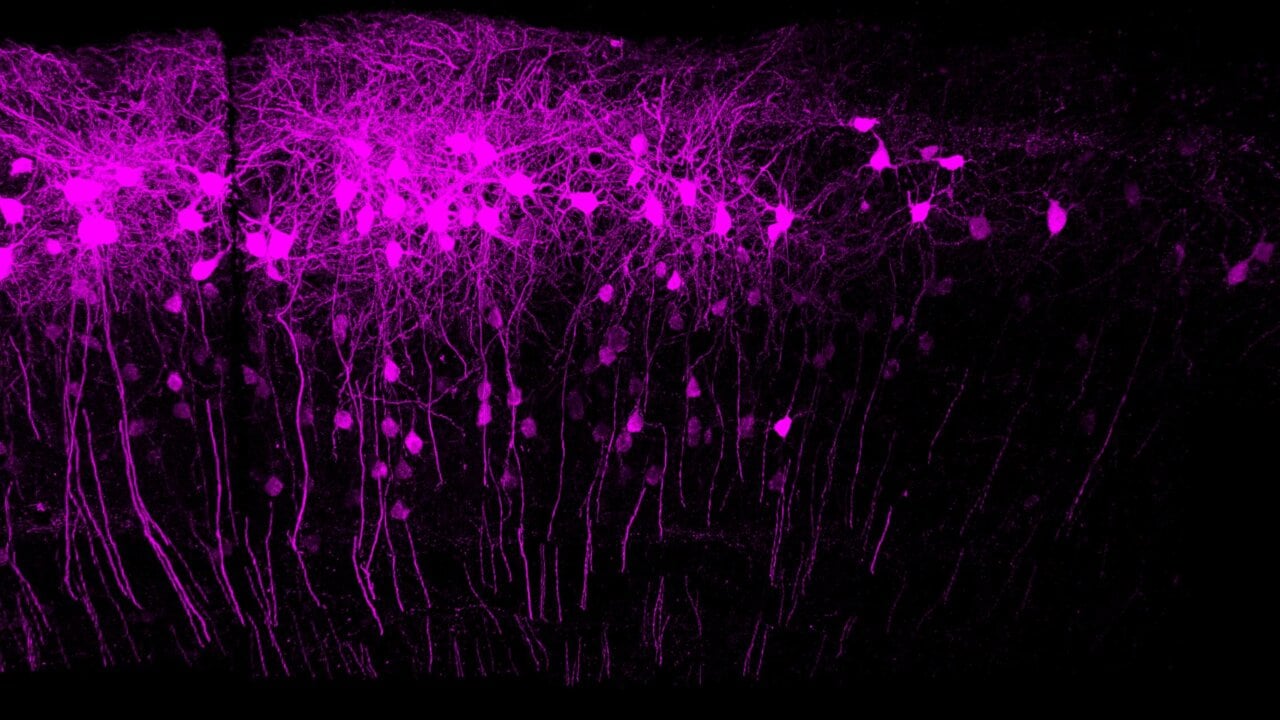

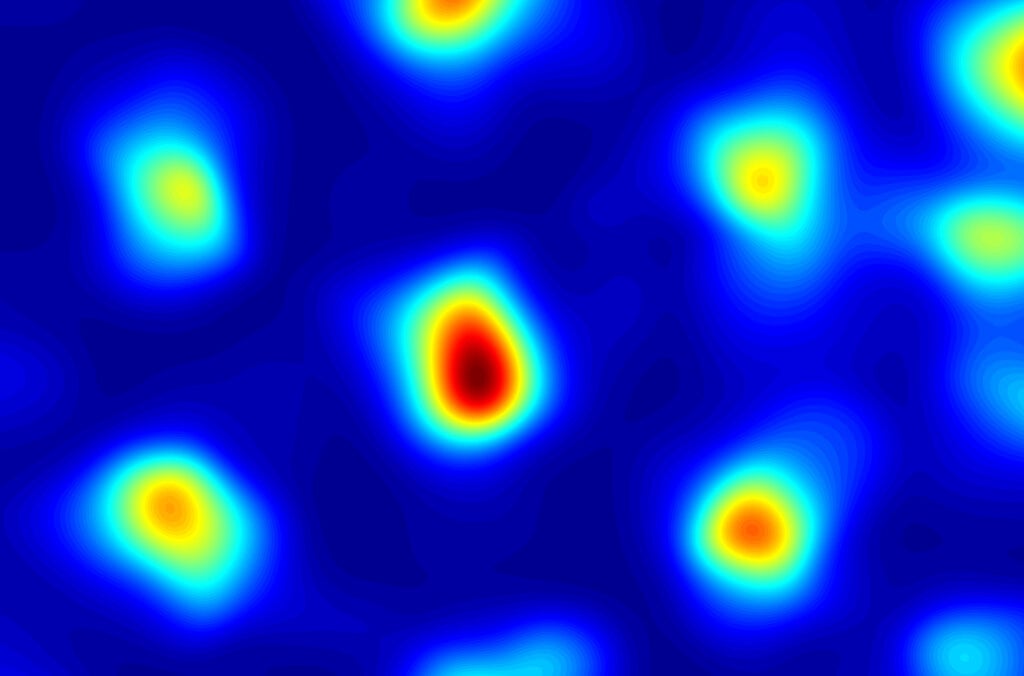

Their research sent the Mosers beyond the place cells to discover the source of the place cells’ information: the entorhinal cortex, a narrow, vertical patch of tissue on the back of the rat’s brain. Certain entorhinal neurons acted just like hippocampal place cells, and fired when the rats were in a particular place. But, curiously, some fired in other places as well. With a large enough sample, they could see the pattern emerge: a hexagonal grid. As the rats moved, they were creating mental grids to represent – and navigate – the space around them. The team published a paper on the discovery of grid cells in 2005.

The discovery of grid cells was groundbreaking, but it was just the beginning. It led to the Mosers identifying neurons that they dubbed border cells, which fire near environmental boundaries. They also found that the brain’s sense of direction is hard-wired according to a minimum of four distinct senses of location, and that memories are organised into 125-millisecond bites.

Meanwhile, Moser’s career continued to flourish. She was promoted to full professor in 2000, when she was 37. She co-founded the Centre for the Biology of Memory in 2002 and became the founding director of the Centre for Neural Computation a decade later. At age 51, she shared with her husband and with their mentor John O’Keefe the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Although Moser and Edvard divorced in 2016, they continue to work together in steadfast pursuit of their shared passion: uncovering the workings of the brain.

“We have a common vision and it is stronger than most.”

May-Britt Moser