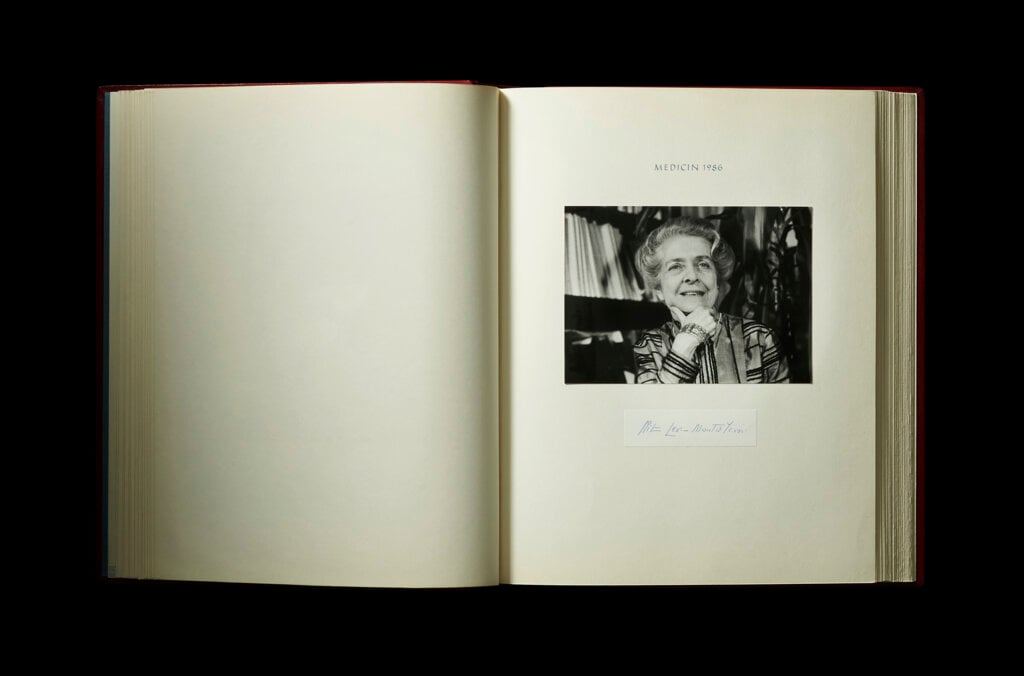

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1986

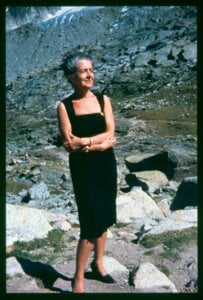

Rita Levi-Montalcini began her scientific career in danger, as a Jew in Fascist Italy. She ended it in triumph, as the neuroembryologist who co-discovered nerve growth factor, a prominent figure in Italian politics, and an active researcher and mentor until her death at the age of 103.

1 (of 2) Rita Levi-Montalcini in her office at Washington University in St. Louis in the late 1950s.

Photo: © Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine. Photographer unknown. Kindly provided by Becker Medical Library

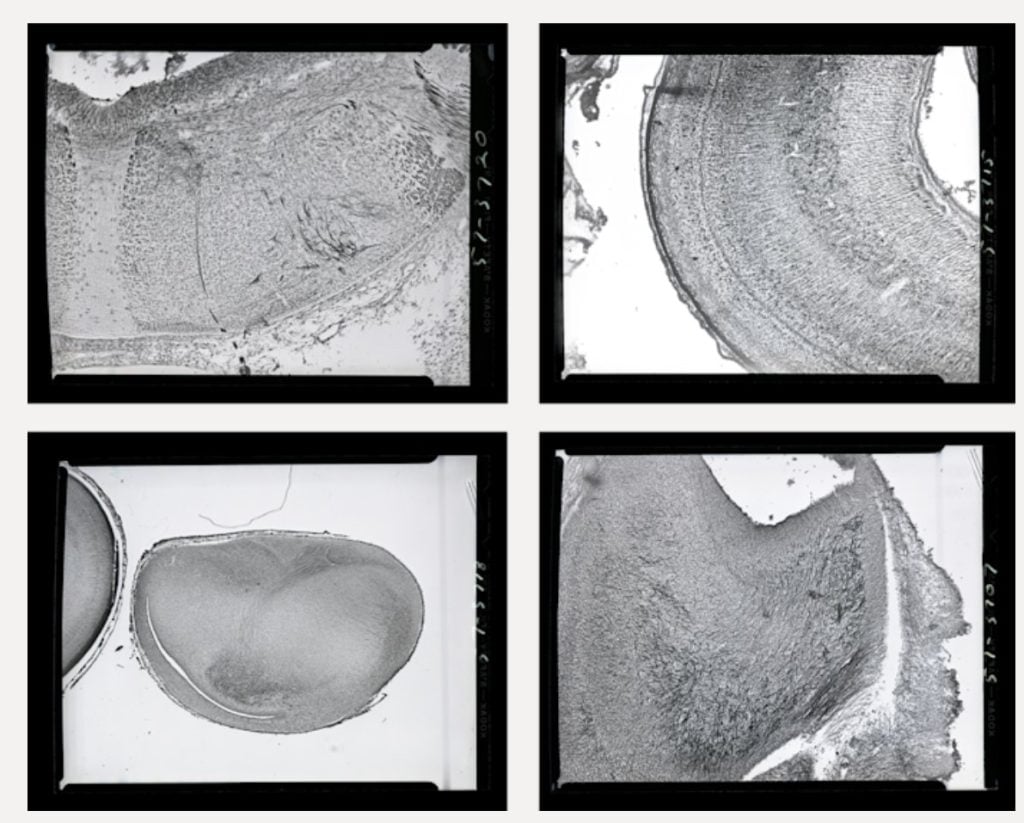

2 (of 2) Image four in a photomicroscopy series of chick embryo cerebellum and optical cortex development, dating from May 1957. These images document some of Levi-Montalcini's work studying the generation of chick optic nerves.

Photo: © Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine

Born in Turin, Italy, in 1909, Rita Levi-Montalcini was raised by an authoritarian father who strongly disapproved of women’s education beyond finishing school. His attitude was both a hindrance and a spur to Levi-Montalcini’s ambitions.

1 (of 2) The Levi-Montalcini family. Rita's father, Adamo Levi, is on the far left. In the front row are the children, Gino, Anna, Paola and Rita. On the far right is Rita's mother, Adele Montalcini.

Photo: Copyright unknown

2 (of 2) Rita Levi-Montalcini at age 11 in Turin, Italy.

Photo: Science Photo Library

“At 20, I realised that I could not possibly adjust to a feminine role as conceived by my father and asked him permission to engage in a professional career.”

Rita Levi-Montalcini

She convinced him to let her study medicine. Woefully undereducated to that point, she crammed years’ worth of Greek, Latin and mathematics into eight months, and then entered medical school at the University of Turin.

Levi-Montalcini graduated with the highest distinction in medicine and surgery in 1936, but, inspired by a professor, histologist and researcher Giuseppe Levi, she was no longer certain she wanted to be a doctor.

She started advanced studies in neurology and psychology, but she was soon kicked out of school, when Mussolini’s newly published 1938 Race Laws forbade any non-Aryan from having a professional or academic career. Levi-Montalcini went to Brussels for a short time to study at a neurological institute, but had to flee when Germany was poised to invade Belgium.

1 (of 2) Notecard from Rita Levi-Montalcini's files, regarding photomicroscopy dating from May 1957.

© Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine

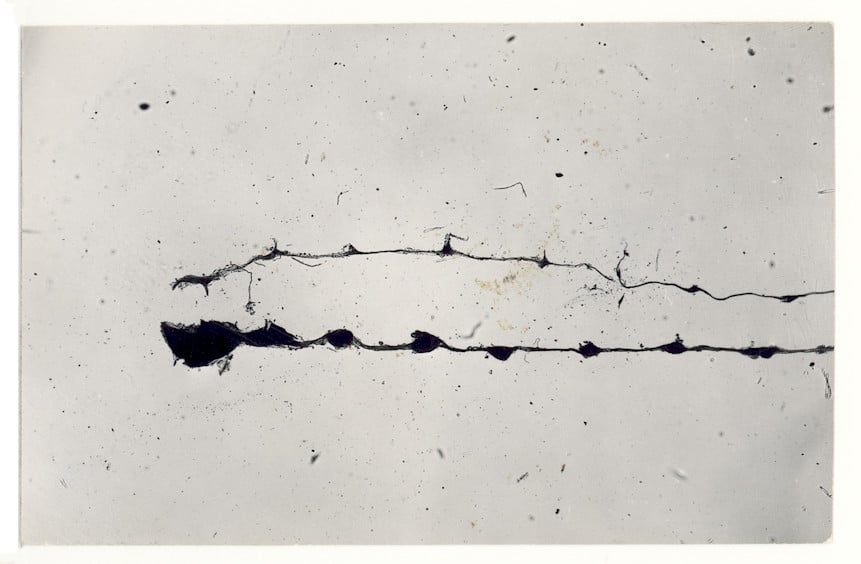

2 (of 2) Nerve fiber photographed in Rita Levi-Montalcini's laboratory.

Photo: © Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine

Back in Turin, forbidden even to set foot at the university, Levi-Montalcini took research matters into her own hands. She built a laboratory in her bedroom, fashioning scalpels from sewing needles, using an ophthalmologist’s tiny scissors and a watchmaker’s forceps. With these tools, and inspired by an article she read by embryologist Viktor Hamburger, she dissected chick embryos and studied their motor neurons (nerve cells responsible for controlling movement) under a microscope.

“I should thank Mussolini for having declared me to be of an inferior race. This led me to the joy of working, not any more unfortunately in university institutes, but in a bedroom.”

Rita Levi-Montalcini

Eventually she even took on an assistant, also expelled from the academy because of his religion: Giuseppe Levi, her medical school mentor. With Levi, Levi-Montalcini came up with a theory about embryonic nerve cells – that they proliferated, started to grow, then died – that ran counter to the model described in Viktor Hamburger’s article. That theory laid the foundation for the modern concept of nerve cell death as a part of normal development. As Jews, they couldn’t publish in Italian journals, but their results were published in foreign journals in the early 1940s.

When the Allies bombed Turin, Levi-Montalcini moved her makeshift lab to the country. When the Germans invaded and started rounding up Jews, she and her family travelled south under false names. They survived, and as the war ended, Levi-Montalcini briefly did become a doctor, treating patients in a refugee camp.

But by then, after the excitement of her hidden research, Levi-Montalcini knew that research in neuroembryology would be her path. Her future was secured in 1946, when Viktor Hamburger himself, curious about their conflicting results, invited her to the Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. “I felt at home the day I landed,” she later wrote. She would stay for 30 years.

1 (of 2) Image 15 in a photomicroscopy series of chick embryo cerebellum and optical cortex development, dating from May 1957. These images document some of Levi-Montalcini's work studying the generation of chick optic nerves.

© Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine

2 (of 2) Image three in a photomicroscopy series of chick embryo cerebellum and optical cortex development, dating from May 1957. These images document some of Levi-Montalcini's work studying the generation of chick optic nerves.

© Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine

Soon after Levi-Montalcini arrived at Hamburger’s laboratory, in 1948, they noticed that a particular type of mouse tumour spurred nerve growth when implanted into chick embryos. Levi-Montalcini and Hamburger figured out the cause: a substance in the tumour that they named nerve growth factor (NGF). The tumour caused similar cell growth in a nerve-tissue culture in the lab. From that point, biochemist Stanley Cohen, her colleague at Washington University, was able to isolate the NGF, a protein subunit, from the tumour.

NGF was the first of many cell-growth factors scientists would find in animals. As Levi-Montalcini – and then others – continued to research NGF, it has given scientists a new way to study neural growth and potentially battle disorders of neural degeneration, such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. NGF is a potential therapeutic target in cancer; it could help treat multiple sclerosis; it could also be a factor in various psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and autism.

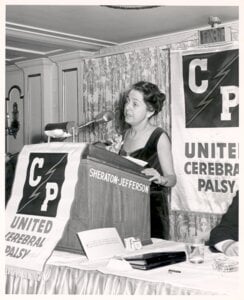

Having faced so many obstacles herself, Rita Levi-Montalcini spent much of the latter part of her career ensuring that other scientists have access to funds, equipment, and support.

For example, she founded and was the first director of the Institute of Cell Biology in Rome. She founded the European Brain Research Institute in 2002. She also established the Rita Levi-Montalcini Foundation, to provide African women “with the tools for a full development of their capabilities.”

Barred in the late 1930s from Italy’s universities, Levi-Montalcini became a beloved figure in her home country when she returned decades later. She received one of Italy’s highest honours in 2001 when she became a senator for life, a role she did not take lightly.

In 2006, at the age of 97, she held the deciding vote in the Italian parliament in a budget dispute. She threatened to withdraw her support unless the government reversed its decision to cut science funding. The funding was put back in and the budget passed, despite the opposition’s attempts to silence her by mocking her age. Or maybe it was because of those attempts. To Levi-Montalcini, obstacles were motivating.

“If I had not been discriminated against or had not suffered persecution, I would never have received the Nobel Prize.”

Rita Levi-Montalcini