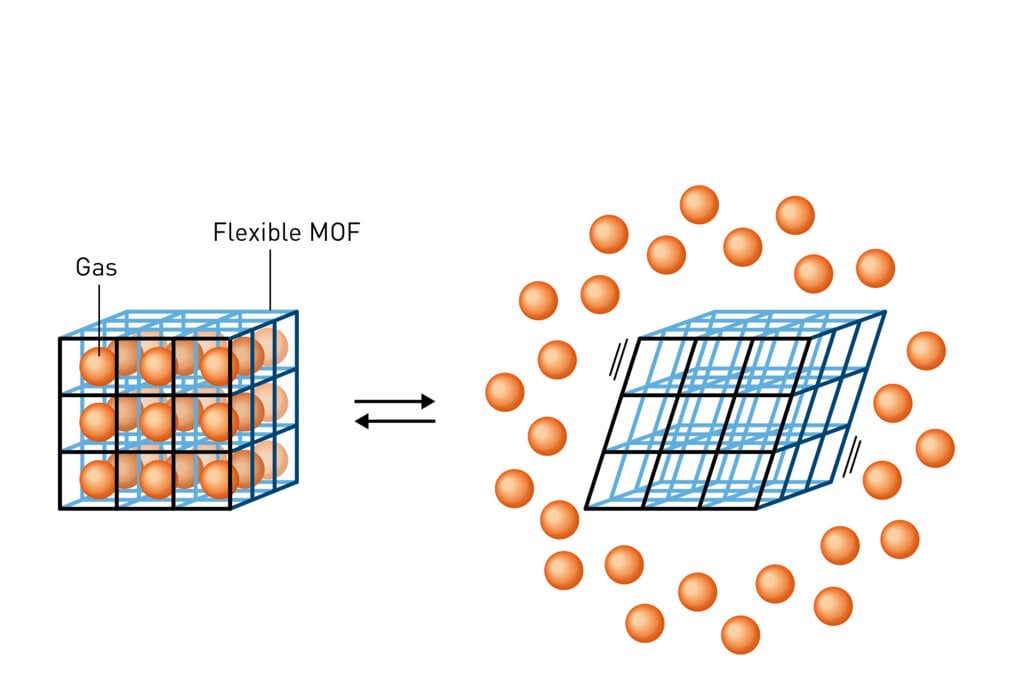

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2025 recognises the development of materials with completely new features. The laureates have created porous metal-organic frameworks (abbreviated as MOFs). These have large cavities that other molecules, such as gases, can move in and out of.

Metal ions + organic molecules become networks (MOF)

Two concepts that are key to understanding the laureates’ discoveries are metal ions and organic molecules.

A metal is an element with a set structure. This means that the atoms are located in certain positions. Metals are characterised by having a metallic sheen and are often good conductors of electricity and heat. They exist in nature and are often found in minerals. A metal ion is a metal atom that has lost one or more electrons and thus has a positive charge.

Organic molecules are chemical compounds that make up all living organisms. They always contain carbon atoms and frequently also hydrogen atoms.

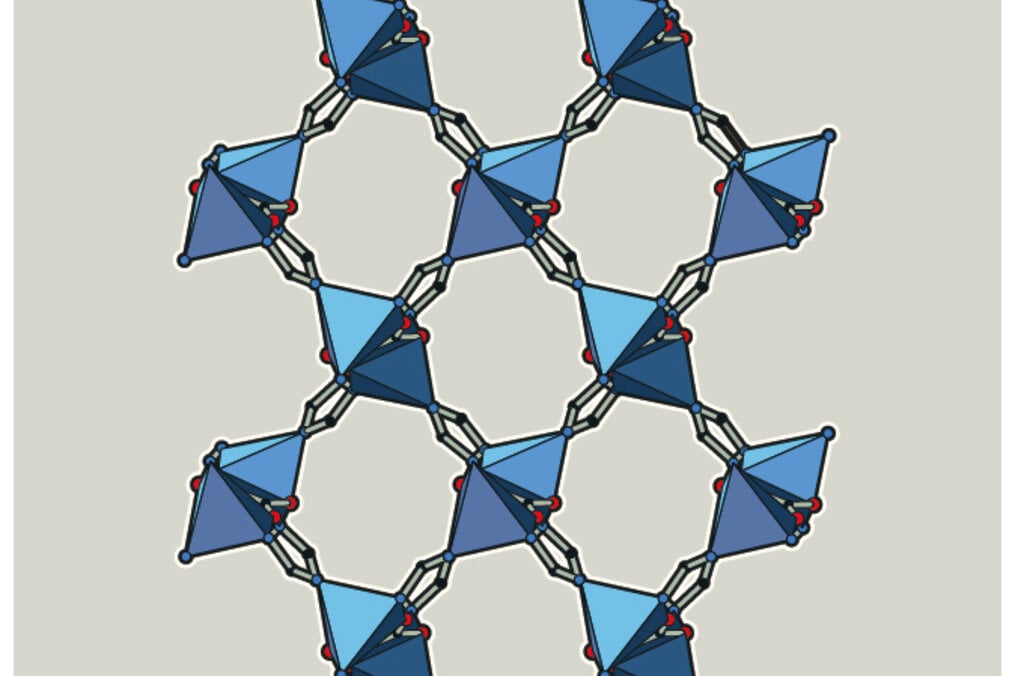

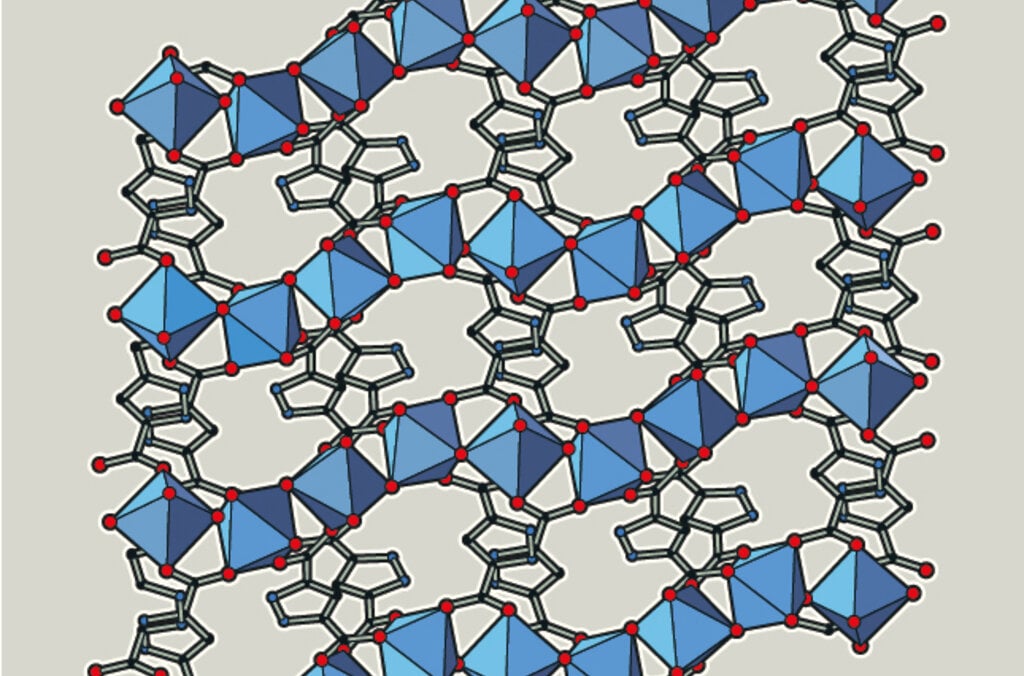

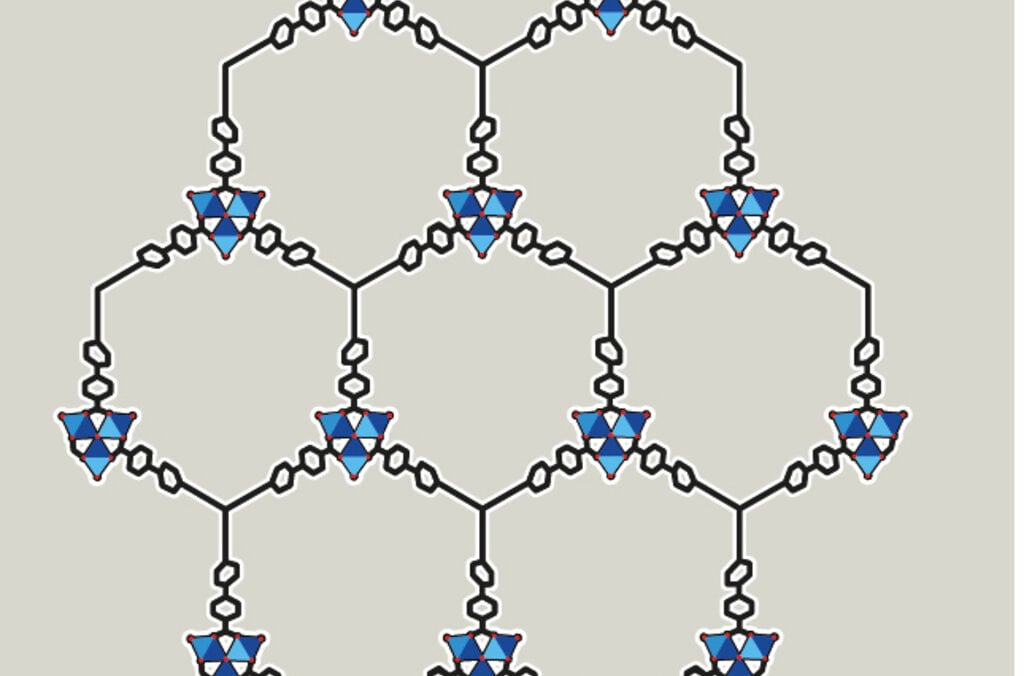

The chemistry laureates have created a completely new material, MOF, which is made up of metal ions and organic molecules. The metal ions function as cornerstones and are joined together with the organic molecules to become a three-dimensional network.

From idea to stable structures

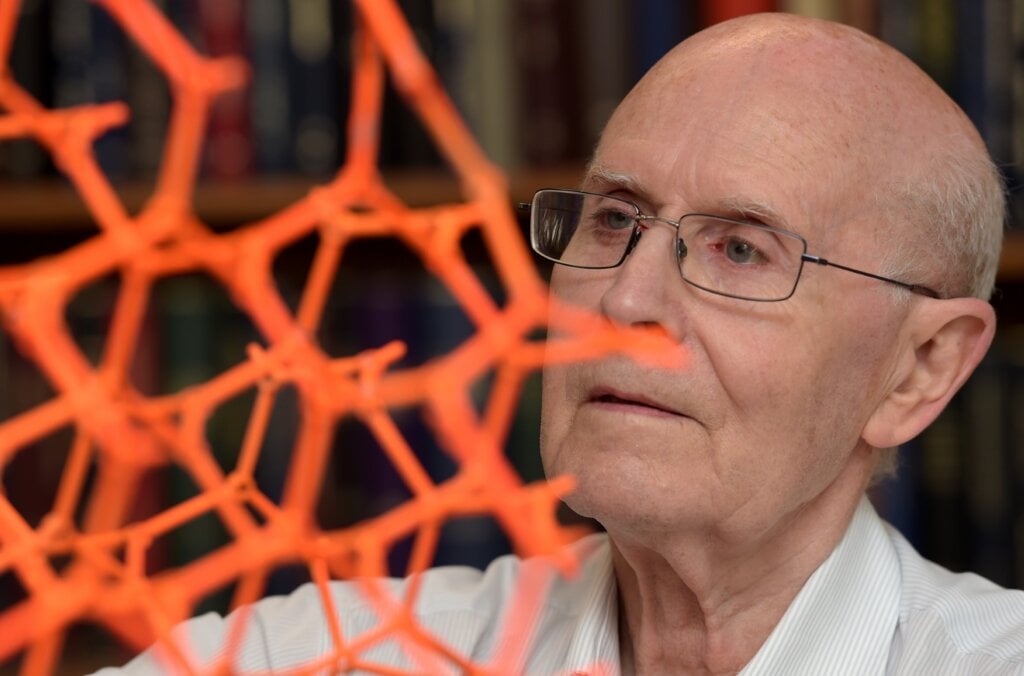

The history of the 2025 chemistry prize begins in Australia already in 1974. While the chemistry teacher Richard Robson was preparing a chemistry lesson, he got an idea. What if it was possible to design new types of molecular structures?

Ten years later, he decided to test his idea, and a couple of years later, he managed to build a well-ordered airy crystal by using copper ions. The first metal-organic framework had been created. This framework was unstable and would easily fall apart, but Robson predicted that the material would be useful in the future.

The other two laureates later laid a solid foundation for the new molecular structures, and Susumu Kitagawa explored the possibilities of creating hollow structures. The final breakthrough came at the end of the 1990s. He managed to create stable structures where the cavities could be filled with gases, which could then be released.

MOFs that hide huge surfaces in their cavities

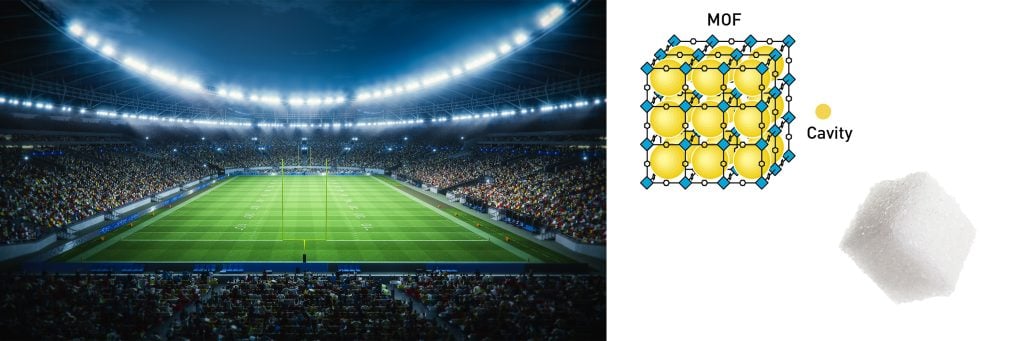

While Kitagawa was experimenting in Japan, Omar Yaghi started to think about how the material could be created in a more controlled way. He wanted to join together chemical building blocks into large crystals.

He managed to develop a new type of MOFs that were incredibly airy but still very stable. Despite the fact that each MOF was no larger than a sugar cube, the surface in the material’s cavity was as big as a football pitch. In other words, it resembled Hermione’s handbag in the Harry Potter stories. Despite its small size, it can hold almost anything.

Omar Yaghi also showed how to alter and customise MOFs to give them new and desired properties.

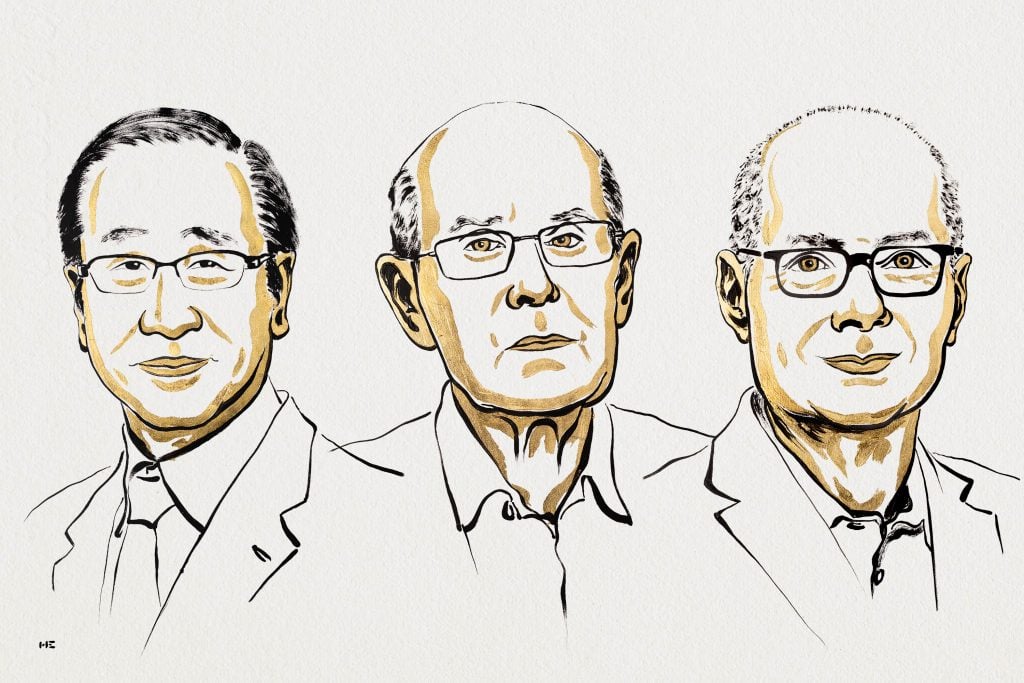

The 2025 Nobel Prize laureates in chemistry

Richard Robson is a professor at the University of Melbourne in Australia. In an interview, he said that many people initially didn’t believe in his idea: “Some people thought it was a whole load of rubbish. But it didn’t turn out that way.”

Susumu Kitagawa is a professor at Kyoto University in Japan. He has said that in his work as a scientist, he has followed an important principle – to try to see “the usefulness of useless”.

Omar Yaghi is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, in the United States. He came to the United States as a refugee from Jordan. His first contact with chemistry was when he sneaked into the school’s closed library and randomly picked a book off the shelf. There, he saw images of molecules that fascinated him.

For the greatest benefit to humankind

MOFs offer previously unimaginable abilities to customise new materials with new features. You can see some examples in the images.

In this short video, you will learn a little bit more about the discoveries made by the laureates and why they confer the greatest benefit to humankind: