Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1995

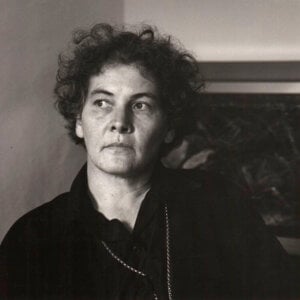

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard approaches biology with the rigour of a scientist and the sensibility of an artist. She helped solve one of biology’s great mysteries: how the genes in a fertilised egg form an embryo. She pursues her love of music and cooking in her spare time, but even her work itself – the quest to understand nature – is, she believes, a creative act.

1 (of 2) The Drosophila or fruit fly, is a popular subject for biological research because their embryos develop extremely rapidly.

Photo: D.G. Mackean

2 (of 2) Drosophila larvae, in a figure from Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard's Nobel Lecture.

Photo: © The Nobel Foundation

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard was born in Germany in 1942, the middle of World War II. Her father was an architect, and both parents painted and were musicians; they brought up their five children to love the arts, and Nüsslein-Volhard both drew and played the flute. But by the age of 12, enchanted with her family’s garden and the farm she visited in the summers, she wanted to be a biologist.

Nüsslein-Volhard was not always a star student. “Decidedly lazy,” even, according to her teachers in high school. At university in Tübingen she says she also got mediocre grades “because I had not always paid attention.”

She began her degree in Frankfurt, studying biology, which she found dull. She tried physics, then switched to the new field of biochemistry. And while she didn’t like that much either, she did like the classes in microbiology and genetics.

In 1969 Nüsslein-Volhard started at the Max Planck Institute for Virus Research, run by Heinz Schaller. Working towards her PhD, Nüsslein-Volhard helped improve Schaller’s methods of purifying RNA polymerase, an essential enzyme that initiates the transcription of RNA from DNA. She also analysed the first step in the process of transcription.

Upon completing her PhD in 1973, Nüsslein-Volhard sought to apply genetics to more than just viruses. Interested in genes that controlled the development of embryos, Nüsslein-Volhard asked Walter Gehring if she could join his lab at the University of Basel, which was studying Drosophila, or fruit flies. Drosophila embryos develop extremely rapidly, which makes them perfect for research.

“I immediately loved working with flies. They fascinated me, and followed me around in my dreams.”

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard

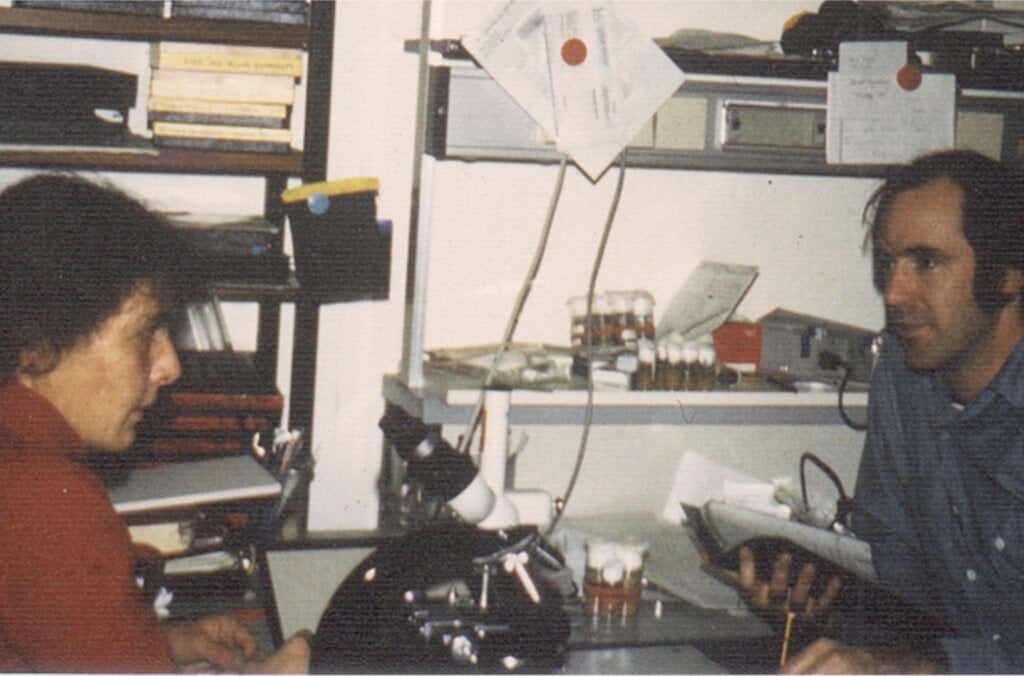

In 1978, after several successful years of researching the bicaudal gene in Drosophila embryos, Nüsslein-Volhard joined the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg. There she would meet the man who became her partner in research: Eric Wieschaus.

Wieschaus and Nüsslein-Volhard invented a process called saturation mutagenesis, where they produced mutations in adult fly genes in order to observe the impact on offspring. Using this method, as well as a dual microscope that allowed them to examine specimens together, they identified 20,000 genes in the chromosomes of fruit flies.

By 1980, when Nüsslein-Volhard was 38, they were able to identify and classify the 15 genes that instruct cells to begin forming a new fly, developing a detailed understanding of how an embryo’s shape is determined by genes.

That understanding had major implications for human reproduction, as well. The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet recognised this impact, and awarded Nüsslein-Volhard and Wieschaus the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1995.

“Creativity is combining facts no one else has connected before.”

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard

Following her award, Nüsslein-Volhard expanded her research beyond Drosophila to vertebrates. Zebrafish were ideal subjects for genetic and developmental studies due to their rudimentary spinal cords, transparent and rapidly growing embryos and – perhaps most importantly – similarities with mammals. Also, Nüsslein-Volhard found them beautiful.

“Initially, I was just struck by the beauty of the fish, like I had been by the segmentation pattern of flies: it’s always nicer to work on something you find beautiful.”

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard

With her Nobel Prize, Nüsslein-Volhard became a public figure, campaigning for increased support of women in science. Nüsslein-Volhard, who never had children, believes women scientists who want to have families are at a disadvantage.

In 2004, she founded the Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard (CNV) Foundation for the Advancement of Science and Research. The foundation gives young women scientists grants for household help and childcare. “The important thing with the CNV Foundation,” she has said, “is to teach women that it’s okay to let people help you because you can’t do everything yourself.”

Nusslein-Volhard’s scientific work continues, now as Director Emeritus at the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen. True to her artistic upbringing, her most recent work explores the scientific basis of beauty in animals.

“When you look at animals like peacocks or birds of paradise, some evolutionary biologists have argued that they grow such extraordinary feathers to prove that they're strong enough to carry them around, or whatever, and of course that's rubbish. It's about beauty.”

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard