“I learned to have pleasure in reading simply because I love stories”

Interview with Abdulrazak Gurnah, February 2022

Nobelprize.org spoke to our 2021 literature laureate on 25 February 2022. He told us about his early days as a reader, the importance of stories and how he sees his work as the same as any other type of job.

For a written version of this interview please see below the video.

Could you tell us about your childhood and where your passion for reading and writing came from?

Abdulrazak Gurnah: I learned to have pleasure in reading simply because I love stories. At first when you’re a child of course the stories are told to you and, in the way that we grew up, children are entirely the responsibility of the women. We lived in a kind of extended family set up. So when I say the women I mean more than one – various aunts and whatever. It was really very nice sometimes to just sit nearby while they’re telling each other these stories or indeed sometimes including us. So it started like that. Then when you learn to read there are books – not very many at the time – I remember the Aesop’s tales for example, in translation of course in Swahili, being one of the earliest books that I was able to read at school. But that’s not the same thing as the reading that comes later, that is more or less sort of reading and rereading the same thing. Children it seems – I know this from my own children – can read the same book 20 times without tiring of it. So I think familiarity is also part of that pleasure of reading, but then later on curiosity takes over and reading becomes a very fulfilling exercise because you learn as well as enjoy.

Was Aesop’s tales your favourite book as a child?

I don’t think Aesop’s tales was my favourite. It was I think my earliest, but I do remember the pictures because there were, of course for a child’s book, lots of illustrations. I do remember in that the picture of the fox leaping for the grapes – that has stayed in my mind forever.

Do you think books that you read when you are young can have a big impression on you?

Yes. And also just simply some of the stories that you hear. You may not remember always the experience of reading, but some of the stories remain for a long time and even for a writer they become sources of places to go to and find out some more and you actually find when you reread a story – like Camaralzaman and Princess Badoura, which is one of those that I do remember and love – you find that in fact, when you go to an adult version of that story, it’s much, much more complicated than you had understood as a child. So there are layers in those stories that you read as a child, which then become possible sources of adventure, reading adventure I mean later on.

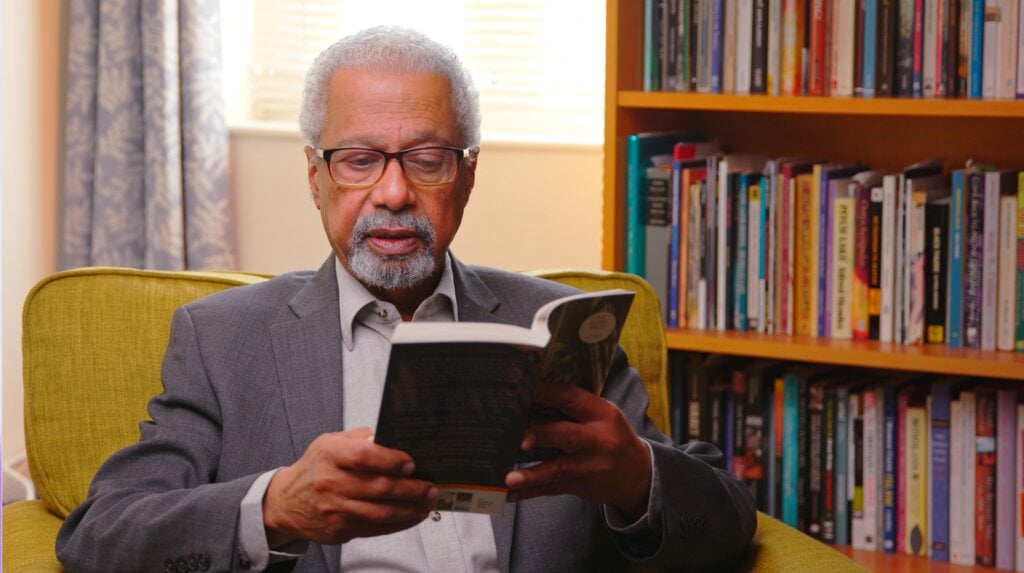

Abdulrazak Gurnah reading an excerpt from his book By the Sea

© Nobel Prize Outreach. Photo: Verri Media

What did you want to be when you were younger? Did you want to be a writer or did you want to be something completely different?

Writing was not really a career that was possible when I was growing up. I didn’t know anybody whose career was a writer, who was a professional writer. So it wasn’t something I aspired to do. I might just as well have aspired to be an astronaut or something like that. It just wasn’t something you knew anybody to be doing. Sometimes you hear children saying, I want to be a train driver or I want to be a computer programmer – but I don’t think I had anything quite like that. I think I was still for a long time open to what might lie ahead. I just enjoyed school and enjoyed learning and enjoyed all of those things. And I just kind of assumed that I’d be doing this for quite a while. Maybe that’s what I wanted to be, just a student.

How did your upbringing shape you and the writer that you have become?

I didn’t know what or how my upbringing shaped me while I was going through it. I don’t suppose many people do unless they’re extremely unhappy at the time or something like that. I also don’t think I would have reflected on it quite so intensely if it hadn’t been for the fact that I was so far away from the place where I grew up. But I think one of the things I had to do in the process of coming to understand, or to coming to terms with being a stranger here in Britain was to think back to things like my upbringing, where I lived, the things we believed. So this is what I mean when I say I’m not sure if I would’ve thought quite so intensely about it. I think being away actually forces you to examine things, in greater detail, perhaps even more critically not just of the events and so on around you, but also of your own participation in that process of living. So I would say it shaped me very much, not in a bad way, not in a way that is destructive, but in a way that forced reflection.

Do you find writing to be a good avenue to explore different issues and to be able to reflect on events that have happened in your life? Or do you just see it as something that is purely pleasurable?

I don’t see writing as purely fun. I do think that there is something necessary about it. This is what I talked about in my Nobel Prize lecture. There are certain imperatives that came up as I began to think about things. And that’s how I started to write. But continuing to write is because you are faced every day with things that are also necessary to be talked about, to be inquired into. And I think for me, this is the drive. It’s to speak about what I see and to do so in a way that both helps me to understand better what it is that I see and also to disseminate, to tell others about it, if they happen to be interested.

I think writing is an important way of extending and understanding our vision to others which is not to say that this is something particularly perceptive or particularly informative. It could be just what we already know. Sometimes we read things and we share in the reflections of others, of the person who’s writing, and perhaps there is some illumination in it that helps us understand, but sometimes it’s just that it endorses things that we have ourselves understood, but not perhaps trusted. So there are various, very complex things happening both in the process of writing but also in the process of the reader engaging with the writing – and I speak as both a reader of course, as well as a writer. That is the pleasure and the fun of the writing process. That you’re not just writing, talking to yourself, but you’re talking to imaginary readers, although for me the imaginary reader is not very specific. You’re not just confiding something to your journal. I know that I will be speaking to people about this and therefore I speak about events in the world. It may be in the form of a story, but a story can be a vehicle for addressing issues as well as addressing injustices as well as indeed just addressing pain and love.

How important is diversity in literature?

I suppose, in order to understand how other people live and what it is that motivates and energises and makes them happy and unhappy you have to know about other people. It’s really quite as simple as that. You have to know. And the best way to know about other people is to hear what they have to say and not to be ventriliquising other people’s lives and trying to explain people away. So in this respect writing from other places, or at least from other perspectives, which might be cultural, social, gender, is one of the most direct ways in which you can hear what other people are saying.

Do you think literature is an important way of hearing other people’s voices and getting access to other people’s world and cultures?

Literature performs different functions of course. Literature also engages us because we take pleasure in it, a kind of complicated pleasure. It depends what you read, of course. But I think at its best literature does that as well as it brings news, tells you things or maybe challenges simplifications that you’ve lived happily with, makes things more difficult for you in that respect. So I see all of those complicated functions. To learn, to enjoy and perhaps also to be challenged, although, that depends on the degree to which you are open to challenges. People can be very difficult in resisting challenges.

Where do you get your ideas from when you write?

The ideas about what to write about just present themselves to you. You don’t have to ache about it, but it seems to me, there are only a limited number of things that really engage a certain kind of writer, that is the writer who maybe writes more reflectively. I think there are things that probably keep returning. Things that are perhaps to do with particular experience, or anxieties that you still want to understand or keep talking about.

I find that when I’ve finished one novel I often think “but I didn’t talk about such and such.” Although it may not be possible to immediately do that, it becomes something at the back of the mind that when there is time, when I can, I will return to this because there’s this aspect that I haven’t done. And maybe I might, and maybe I might not, but it’s in this way that the ideas kind of turn around and percolate, and kind of hang around for a while. And then, it may be something you see, something you read that provides a happy impulse.

So when an idea begins to emerge like this, then you follow it up by reading some more about it, thinking some more about it, making some notes. So it isn’t just an idea comes and you think, oh I think that I will write about this, but it really takes a little bit of a while for it to rumble along before it becomes specific or concrete enough.

For any aspiring writers, is there a particular piece of advice that you would give to them?

The best advice you can give a writer is just write. There is no simple way. There is no way in which you can say, if you stand on your head twice a day, that this will enable you to write. You just have to write and keep writing and don’t be discouraged and just keep writing. Now it could be you’re in the wrong business in which case sooner or later you’ll discover that. But you won’t discover that by querying yourself, you’ll only discover that by the full process of doing the writing. And then if that doesn’t work – you can’t persuade anybody at all to be interested in it – then could be that you’re in the wrong business. But even then I wouldn’t give up. I would still keep pressing on.

What’s your favourite thing about writing?

Oh, I don’t know – when it’s finished! Writing is best when it’s complete, when it’s finished . The process itself has its pleasures. Of course now and then at the end of the day’s work, when you can get up and say, that’s all right, I did okay today, but there also many days when you get up and you think, what a load of rubbish! I’m going to have to go through all that again tomorrow. But I think the best moment in writing is when you think, yep, I think it’s done.

What type of books do you like reading and who is your favourite author?

I have favorite authors rather than an author that I can name and these vary a little bit. If I look back 10 years ago, I don’t know who I would’ve said the writers were. Maybe one or two are still with me, but you move on. Recently the things that I’ve enjoyed reading are writers from Africa, like Maaza Mengiste, Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor. These are people who are doing brilliantly well I think, and in both of those cases, they’ve just published their second novels. So very early in their writing careers. But also I admire writers like J.M. Coetzee, Nuruddin Farah, Michael Ondaatje, I can name several. So it isn’t a matter of favourite. I’m open to all these brilliant writers and I read as many of them as time and chance allows – chance in the sense of you don’t always hear about writers or you hear about them but you don’t have time to read all of them, but there are many favourites.

And what do you enjoy doing outside of writing?

Watching cricket, I enjoy watching cricket. I enjoy gardening. I enjoy cooking. I enjoy reading, listening to music. You see just an ordinary kind of thing that everybody does.

2021 literature laureate Abdulrazak Gurnah receives his Nobel Prize medal and diploma in London, UK.

© Nobel Prize Outreach. Photo: Hugh Fox

How has life changed for you after being awarded this prize?

Well, the award of the prize was a great honour. I’m very proud of that honour. Because it is such a global event it means that a lot of people want to know about me, want to know me, want to speak to me. Also as a result of the prize many publishers in many different languages who hadn’t published any of my work before are now doing so. So they want their journalists to tell their readers about me. So I’ve been talking to a lot of people since the award of the prize and that really has taken up quite a lot of my time since then. So what has changed since the award of the prize? It’s difficult to assess exactly because I’m just talking all the time to people explaining things. What I do know is that it hasn’t really possible to do any writing during this time, but that’s fine because I know it’ll be like this for a while, but then at some point it’ll be possible to return and write again.

We see that the Nobel Prize often inspires people. Who or what inspires you to write?

What inspires me to write, is to be able to speak truthfully about what I see and the things that concern me. So it’s not just my eyes are open and therefore, whatever strikes my eye I want to write about it, but there are these concerns about… for example I’m very interested in the way people can retrieve something from trauma, so I’m thinking not only of asylum seekers or refugees, but also of life, of the way people in life are able to get something out of mischance, out of traumatic events.

I’ve always been interested in the way families work, particularly the way both power and kindness go along together. Of course, most families love each other, but at the same time there are, what seem like power struggles going on within families. I’m interested in writing about that and the complexity of that and how out of kindness a kind of a sort of unkindness comes as well – requiring obedience that you don’t shame us by doing this, or by doing that. Particularly, I’m thinking of the way women are treated, in our culture anyway, and in many other cultures. Those are the kinds of things that make me want to write. Things that, as I say, my sense of this needs to be spoken about. I need to say something about this. And of course also the other thing that makes me want to write is to create something which is beautiful and pleasurable.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

First published: March 2022

Book tips

Curious about 2021 literature laureate Abdulrazak Gurnah but can’t decide which of his books to start with? Here three members of the Swedish Academy give their recommendations.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.