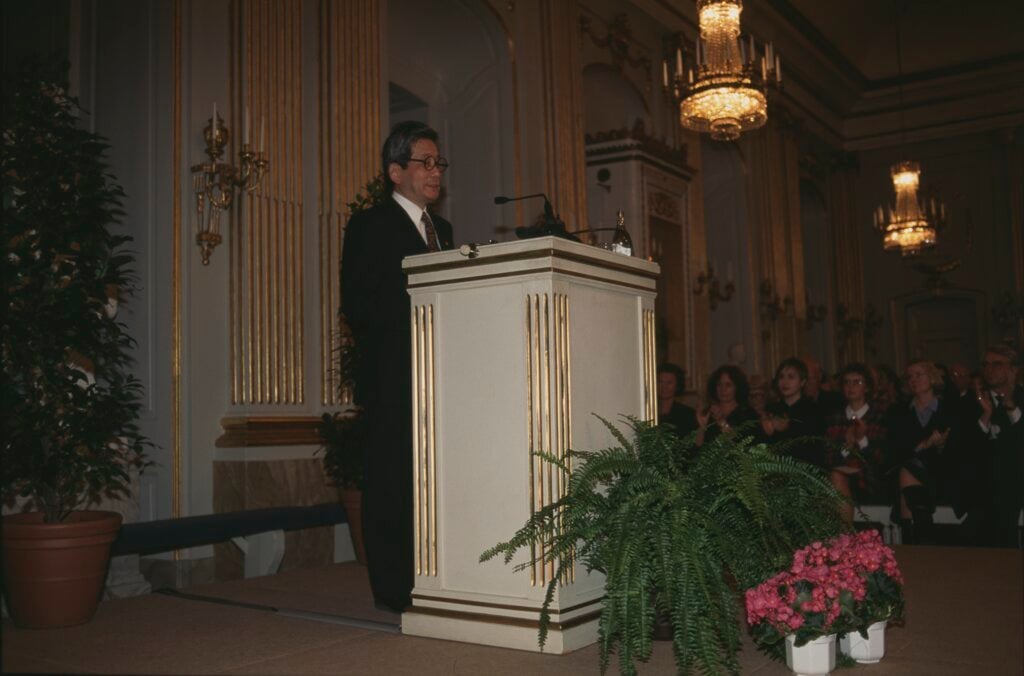

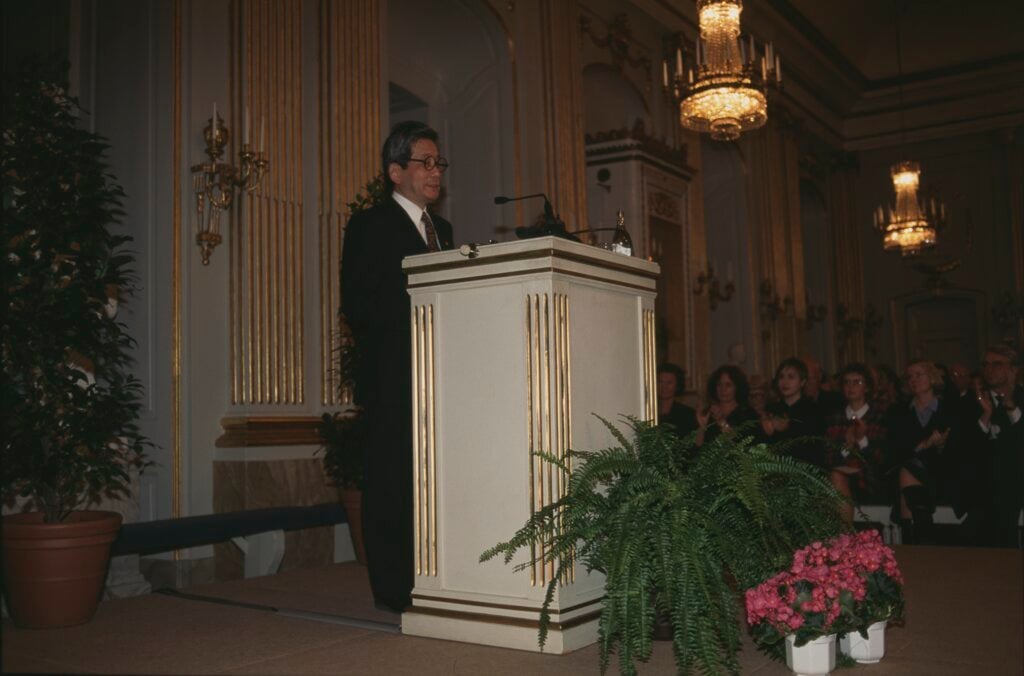

Kenzaburo Oe – Nobelföreläsning

English

Swedish

Japanese (pdf)*

Nobelföreläsning, 7 december 1994

Japan, det kluvna, och jag själv

Under det senaste katastrofala världskriget var jag en liten pojke och bodde i en avlägsen skogig dalgång på ön Shikoku i den japanska arkipelagen, tusentals kilometer härifrån. På den tiden var det två böcker som verkligen fascinerade mig: Huckleberry Finns äventyr och Nils Holgerssons underbara resa genom Sverige. Hela världen var vid denna tid översköljd av vågor av fasa. Läsningen av Huckleberry Finn gjorde det möjligt för mig att rättfärdiga min vana att nattetid bege mig upp i bergens skogar och sova bland träden med en känsla av trygghet som jag aldrig kunde finna inomhus. Huvudpersonen i Nils Holgerssons underbara resa förvandlas till en liten varelse som förstår fåglarnas språk och ger sig ut på en äventyrsfylld resa. Från denna berättelse hämtade jag lustfyllda känslor av olika slag. För det första fick jag klart för mig, där jag levde i den djupa skogen på ön Shikoku på samma sätt som mina förfäder hade gjort för länge sedan, att denna värld och detta sätt att leva i sig innebar en sann befrielse. För det andra blev jag förtjust i Nils och identifierade mig med honom, en busig liten pojke som medan han reser genom Sverige samarbetar med och kämpar för vildgässen och härigenom förvandlas till en pojke som fortfarande är oskuldsfull men ändå fylld av både självkänsla och anspråkslöshet. När Nils till slut återvänder hem vågar han tala med sina föräldrar. Jag tror att den glädje jag fick ut av berättelsen ytterst ligger i språket, ty jag kände mig renad och upplyftad av att få följa Nils i talet. Hans ord lyder som följer: “‘Mor och far, jag är stor, jag är människa igen!’ ropade han.” I fransk översättning: “‘Maman, Papa! Je suis grand, je suis de nouveau un homme!’ cria-t-il.”

Jag fascinerades speciellt av orden “je suis de nouveau un homme!” Under min uppväxttid drabbades jag av ständiga prövningar på livets olika områden i familjen, i mitt förhållande till det japanska samhället och i mitt allmänna levnadssätt under senare hälften av nittonhundratalet. Jag har överlevt genom att ge uttryck åt dessa mina lidanden i romanform. Härvid har jag kommit på mig själv med att nästan suckande upprepa orden: “je suis de nouveau un homme!” Att på detta sätt tala om mig själv är kanhända föga passande för denna plats och detta tillfälle. Men låt mig ändå få säga att grunden för mitt skrivande alltid har varit att utgå ifrån mitt privata liv och sedan sammanlänka det med samhället, staten och världen. Jag hoppas ni ursäktar att jag ägnar ytterligare en liten stund åt mitt privata liv.

För ett halvt sekel sedan, när jag bodde djupt inne i den där skogen, läste jag Nils Holgerssons underbara resa och kände att den rymde två profetior. Den ena var att jag en dag kanske skulle lära mig att förstå fåglarnas språk. Den andra var att jag en dag kanske skulle få flyga iväg tillsammans med mina kära vildgäss – helst till Skandinavien.

Efter mitt giftermål föddes vårt första barn med ett mentalt handikapp. Vi gav honom namnet Hikari, som betyder “ljus” på japanska. Som liten reagerade han bara på vilda fåglars kvitter och aldrig på mänskliga röster. En sommar när han var sex år gammal bodde vi i vårt hus på landet. Han hörde ett par vattenrallars (Rallus aquaticus) skarpa läten bortifrån sjön bakom dungen och han sa med samma speakerröst som på det inspelade bandet med vildfågelsång: “Detta är vattenrallar”. Detta var första gången någonsin som min son uttalade mänskliga ord. Från och med då började min fru och jag att verbalt kommunicera med vår son.

Hikari arbetar nu på en yrkesskola för handikappade, en institution som bygger på ideer från Sverige. Under tiden har han komponerat musikstycken. Det var fåglarna som var ursprunget och medlet till att han började komponera mänsklig musik. På mina vägnar har således Hikari uppfyllt profetian om att jag en dag kanske skulle förstå fåglarnas språk. Jag måste också säga att mitt liv skulle ha varit omöjligt utan min hustru, med hennes flödande rikedom på kvinnlig styrka och visdom. Hon har varit själva personifikationen av Akka, Nils ledargås. Tillsammans med henne har jag flugit till Stockholm, och därmed har också den andra av profetiorna till min oerhörda glädje gått i uppfyllelse.

Kawabata Yasunari, den förste japanske författare som beträtt detta podium som Nobelpristagare i litteratur, höll en Nobelföreläsning som bar titeln Japan, det sköna, och jag själv. Den var på samma gång mycket vacker och mycket vag, vague. Jag använder det engelska ordet vague som likvärdigt med det japanska ordet aimaina. Detta japanska adjektiv kan översättas till engelska på flera olika sätt. Det slags vaghet som Kawabata medvetet valt finns med redan i själva titeln på hans föreläsning. Den kan återges som “jag själv av det sköna Japan”. Vagheten i hela titeln härrör ifrån den japanska partikeln “no” (bokstavligen engelskans “of”) som binder samman “mig själv” och “det sköna Japan”.

Vagheten i titeln ger utrymme för flera olika tolkningar av dess innebörd. Den kan betyda “jag själv som en del av det sköna Japan”, där partikeln “no” betecknar förhållandet mellan det substantiv som följer efter den och det substantiv som föregår den som ett ägande, eh samhörighet eller en tillhörighet. Den kan även betyda “det sköna Japan och jag själv”, varvid partikeln förenar de båda substantiven appositionellt, som fallet är i den engelska titeln på Kawabatas föreläsning, som översatts av en av de främsta amerikanska specialisterna på japansk litteratur. Hans översättning lyder: “Japan, the beautiful, and myself”. I denna expertöversättning är il traduttore (översättaren) inte på minsta sätt någon traditore (förrädare).

Under denna titel talade Kawabata om ett unikt slag av mysticism som förekommer inte bara i japanskt tänkande utan även vidgat i det orientaliska tänkandet. Med “unikt” avser jag här dragningen mot zenbuddhismen. Även som den nittonhundratalsförfattare Kawabata är beskriver han sitt sinnestillstånd med ord hämtade från dikter skrivna av medeltida zenmunkar. De flesta av dessa dikter handlar om den språkliga omöjligheten att säga sanningen. Enligt sådana dikter finns orden instängda inom sina slutna skal. Som läsare kan man inte förvänta sig att det någonsin ur dessa dikter skall komma ord som kan nå fram till en. Man kan aldrig förstå eller känna sig tilltalad av dessa zendikter annat än genom att ge upp sig själv och beredvilligt föras rakt in i dessa ords slutna skal.

Vad fick Kawabata att fatta det djärva beslutet att läsa upp dessa ytterligt esoteriska dikter på japanska inför publiken i Stockholm? Jag ser nästan nostalgiskt tillbaka på det rättframma mod som han uppnådde mot slutet av sin framstående bana och med vilket han avgav en sådan trosbekännelse. Kawabata hade varit en konstens pilgrim i flera decennier och under dessa hade han skapat en mängd mästerverk. Efter dessa pilgrimsår var det endast genom att avlägga en bekännelse om hur fascinerad han blivit av dessa otillgängliga japanska dikter, som trotsar varje försök att till fullo förstå dem, som han kunde tala om “Japan, det sköna, och jag själv”, det vill säga om den värld i vilken han levde och den litteratur som han skapade.

Det är dessutom värt att notera att Kawabata avslutade sin föreläsning som följer:

Mina verk har beskrivits som verk av tomhet, men det får inte förstås som västerländsk nihilism. Den andliga grunden framstår som helt annorlunda. Dogen gav sin dikt om årstiderna titeln “Inneboende verklighet”, och även när han besjöng årstidernas skönhet var han djupt försjunken i zen.

Även här spårar jag en modig och rättfram självkänsla. Å ena sidan förklarar sig Kawabata i allt väsentligt tillhöra zenbuddhismens filosofiska tradition och den estetiska känslighet som genomsyrar orientens klassiska litteratur. Men å andra sidan vinnlägger han sig om att särskilja den tomhet som tillskrivs hans egna verk ifrån västerländsk nihilism. Härmed vänder han sig oförblommerat till de mänsklighetens kommande generationer till vilka Alfred Nobel satte sitt hopp och sin tro.

Uppriktigt sagt känner jag mig mindre andligt besläktad med Kawabata, min landsman som stod här för tjugosex år sedan, än med den irländske poeten William Butler Yeats, som tilldelades Nobelpriset i litteratur för sjuttioett år sedan, när han var ungefär lika gammal som jag. Jag gör givetvis inte anspråk på att jämföra mig med diktargeniet Yeats. Jag är blott en ödmjuk efterföljare bosatt i ett land som ligger mycket långt ifrån hans. Som William Blake, vars verk Yeats gav nytt värde och återskänkte det höga anseende det åtnjuter i detta århundrade, en gång skrev: “Över Europa och Asien till Kina och Japan likt ljungeldar”.

Under de senaste åren har jag varit sysselsatt med att skriva en trilogi som jag önskar skall bli krönet på min litterära verksamhet. Hittills har de första två delarna givits ut och jag har nyligen avslutat den tredje och sista delen. På japanska har den fått titeln “Ett flammande grönt träd”. Denna titel har jag hämtat från en strof ur Yeats dikt “Vacillation”:

A tree there is that from its topmost bough

Is half all glittering flame and half all green

Abounding foliage moistened with the dew …

(W. B. Yeats: Vacillation, 11–13)

Min trilogi är i själva verket genomdränkt av flödande influenser från hela Yeats diktning. Med anledning av Yeats Nobelpris lade den irländska senaten, för att gratulera honom, fram en motion med bland annat följande innehåll:

” … det erkännande som nationen, genom hans framgång, har vunnit för

sina framstående bidrag till kulturen i världen.”

” … ett släkte som hitintills inte hade vunnit tillträde till kretsen av nationer

med inbördes respekt för varandra.”

” … Vår civilisation kommer att bygga sitt värde på senator Yeats namn.”

“det kommer alltid att finnas en fara för krigshets bland människor som befinner

sig på tillräckligt avstånd ifrån förstörelselustans vanvett.”

(Nobelpriset: Gratulationer till senator Yeats)

Yeats är den författare i vars kölvatten jag skulle vilja följa. Jag skulle vilja göra det för en annan nations skull, en nation som nu har “vunnit tillträde till kretsen av nationer med inbördes respekt för varandra”, om än snarast till följd av sin elektroniska teknologi och sin biltillverkning. Och jag skulle vilja göra det som medborgare i en av dessa nationer som har hetsats in i “förstörelselustans vanvett”, såväl på sin egen jord som på sina grannländers.

Som medborgare i det nutida Japan och med våra gemensamma bittra minnen från det förflutna inpräglade i själen kan jag inte förena mig med Kawabata i yttrandet: “Japan, det sköna, och jag själv”. Nyss berörde jag “vagheten” i titel och innehåll i Kawabatas föreläsning. I resten av min föreläsning skulle jag vilja använda ordet “kluven”, enligt den distinktion som har gjorts av den framstående brittiska poeten Kathleen Raine; en gång sade hon om William Blake att han snarare var kluven än vag. Jag kan inte tala om mig själv annat än genom att uttrycka det: “Japan, det kluvna, och jag själv”.

Min erfarenhet är att dagens Japan, efter etthundratjugo år av modernisering alltsedan landet öppnades, är kluvet mellan två motsatta poler. Också jag lever som författare med denna polarisering inpräglad i mig likt ett djupt ärr.

Denna kluvenhet, som är så stark och så genomgripande att den splittrar både staten och dess folk, kommer till synes på olika sätt. Moderniseringen av Japan har inriktats på att lära av och efterlikna västerlandet. Men Japan är trots allt beläget i Asien och har hållit hårt fast vid sin traditionella kultur. Japans kluvenhet drev landet till en ställning som inkräktare i Asien. Å andra sidan förblev det moderna Japans kultur, som ju förutsatte en total öppenhet gentemot väst, under lång tid någonting dunkelt och outgrundligt för västerlandet, eller den blev åtminstone ett hinder för förståelsen från västs sida. Till yttermera visso drevs Japan till isolering från andra asiatiska länder, inte bara politiskt utan även socialt och kulturellt.

I den moderna japanska litteraturhistorien var det de efterkrigsförfattare som äntrade den litterära scenen omedelbart efter det senaste kriget, med djupa sår efter katastrofen men ändå fyllda av hopp om pånyttfödelse, som visade störst uppriktighet och medvetenhet om sin uppgift. Under svåra våndor försökte de gottgöra de omänskliga grymheter som hade begåtts av de japanska trupperna i asiatiska länder samtidigt som de ville överbrygga de djupa klyftor som fanns inte bara mellan västerlandets industriländer och Japan utan även mellan afrikanska och latinamerikanska länder och Japan. Endast på detta sätt ansåg de sig ödmjukt kunna söka försoning med den övriga världen. Det har alltid varit min strävan att inte släppa taget om den litterära tradition som gått i arv från dessa författare.

Den nutida staten Japan och dess folk kan i sin postmoderna fas inte präglas av annat än ambivalens. Mitt i Japans moderniseringsprocess inträffade det andra världskriget, ett krig som hade framsprungit ur en förvillelse i just själva moderniseringsprocessen. Nederlaget i detta krig för femtio år sedan erbjöd en möjlighet för Japan och japanerna att i egenskap av detta krigs drivande kraft försöka åstadkomma en pånyttfödelse ur det enorma elände och lidande som har skildrats av de japanska författarnas “efterkrigsskola”. Som moralisk stötta för de japaner som eftersträvade en sådan pånyttfödelse tjänade demokratin som idé samt deras egen fasta föresats att aldrig mer föra krig. Paradoxalt nog var det japanska folk och den japanska stat som levde med en sådan moralisk stötta ingalunda oskyldiga utan var besudlade av sitt eget förflutna som angripare av andra asiatiska länder. Denna moraliska stötta påverkades också av de döda offren för de kärnvapen som för första gången hade använts i Hiroshima och Nagasaki liksom av de överlevande och deras avkomlingar som utsatts för radioaktiv strålning (däribland tiotusentals med koreanska som modersmål).

På senare år har man riktat kritik mot Japan och antytt att landet borde ställa fler trupper till Förenta Nationernas förfogande och därigenom spela en aktivare roll för att bevara och återställa freden i olika delar av världen. Varje gång vi hör sådan kritik blir vi tunga till sinnes. Efter andra världskrigets slut var det ett kategoriskt imperativ för oss att i en central artikel av vår nya författning deklarera att vi för alltid skulle avhålla oss från krig. Vi japaner har valt principen om evig fred som moralisk grundval för vår pånyttfödelse efter kriget.

Jag är förvissad om att principen möter störst förståelse i västländerna med deras långa tradition av tolerans för värnpliktsvägran av samvetsskäl. I själva Japan har det hela tiden förekommit försök från olika håll att ur författningen stryka artikeln om att avhålla sig från krig och man har i detta syfte utnyttjat varje tillfälle till att dra fördel av påtryckningar från utlandet. Men att ur vår författning stryka principen om evig fred vore ingenting annat än ett förräderi mot Asiens folk och mot offren för atombomberna i Hiroshima och Nagasaki. För mig som författare är det inte svårt att föreställa sig vad ett sådant förräderi skulle leda till.

Den japanska författning som gällde före kriget och som postulerade enväldet såsom överlägset den demokratiska principen åtnjöt visst stöd hos den breda massan. Trots att vi nu har den halvsekelgamla nya författningen, lever det i själva verket på vissa håll kvar en folklig böjelse att stödja den gamla, och det inte enbart av nostalgiska skäl. Om Japan skulle institutionalisera en annan princip än den som vi nu i femtio år har bekänt oss till, skulle detta omintetgöra den fasta föresats som vi deklarerade i efterkrigsruinerna av vårt misslyckade försök till modernisering, den fasta föresatsen att upprätta och göra gällande begreppet universell humanitet. Detta kan jag inte låta bli att se som en fara, och då talar jag som en vanlig enkel individ’.

Det som jag här i min föreläsning kallar Japans “kluvenhet” är ett slags kroniskt sjukdomstillstånd som har rått under hela den moderna tiden. Japans ekonomiska välstånd går inte heller fritt från det, åtföljt som det är av alla möjliga slags potentiella faror som hänger samman med strukturen hos världsekonomin och omsorgen om vår miljö. “Kluvenheten” i detta avseende tycks hela tiden bli större. Den kanske är ännu mer uppenbar för övriga världens kritiska ögon än för oss inom landet. Djupt nere i den första efterkrigstidens ekonomiska bottenläge lyckades vi hitta en förmåga att uthärda och att aldrig förlora hoppet om att kunna återhämta oss. Det kanske låter konstigt att säga så, men vi tycks besitta lika stor förmåga att uthärda vår ängslan för de ödesdigra konsekvenser som vårt nuvarande välstånd ger upphov till. Sett från en annan sida verkar det nu vara på väg att uppstå en ny situation som innebär att Japans välstånd inlemmas i den starka potentiella expansionen inom såväl produktion som konsumtion i Asien som helhet.

Jag tillhör de författare som har en önskan att skapa seriösa litterära verk som skiljer sig ifrån de romaner som bara återspeglar Tokyos enorma konsumtionskulturer och hela världens subkulturer. Vilken identitet skall jag då söka som japan? W. H. Auden definierade en gång romanförfattaren på följande sätt:

... , among the Just

Be just, among the Filthy filthy too,

And in his own weak person, if he can,

Must suffer dully all the wrongs of Man.

(“The Novelist”, 11–14)

Detta har blivit mitt sätt att leva (eller “habit of life”, för att tala med Flannery O’Connor) eftersom jag är författare till yrket.

För att definiera en önskvärd japansk identitet skulle jag vilja välja ordet “anständig”, som är ett av de adjektiv som George Orwell ofta använde, vid sidan av ord som “human”, “sund” och “behaglig”, när han skulle beskriva de romanfigurer han var mest förtjust i. Detta bedrägligt enkla epitet kanske framstår i bjärt kontrast till ordet “kluven” som jag använde när jag identifierade mig i “Japan, det kluvna, och jag själv”. Det föreligger en omfattande och ironisk brist på överensstämmelse mellan det intryck japanerna ger när de betraktas utifrån och det intryck de själva vill ge.

Jag hoppas att Orwell inte skulle komma med några invändningar om jag använde ordet “anständig” som synonym till “humanistisk”, eller på franska humaniste, ty gemensamt för båda dessa ord är att de inbegriper egenskaper som tolerans och mänsklighet. Bland våra förfäder fanns några pionjärer som flitigt bemödade sig om att bygga upp den japanska identiteten som just “anständig” eller “humanistisk”.

En sådan person var framlidne professorn Kazuo Watanabe, som forskade i den franska renässansens litteratur och tänkande. Omgiven av den vanvettiga patriotiska glöd som härskade strax före och i mitten av andra världskriget närde Watanabe ensam drömmen om att kunna sammanföra den humanistiska människosynen med den traditionella japanska känsla för skönhet och natur som lyckligtvis inte helt hade blivit utrotad. Jag måste skyndsamt tillägga att professor Watanabe hade en uppfattning om skönhet och natur som skilde sig från den som formuleras av Kawabata i hans “Japan, det sköna, och jag själv”.

Det sätt som Japan hade använt för att bygga upp en modern stat efter västerländsk modell var katastrofalt. På sätt som skilde sig från men ändå delvis sammanföll med denna process hade japanska intellektuella försökt överbrygga klyftan mellan väst och det egna landet där denna var som allra djupast. Det måste ha varit ett mödosamt arbete, eller travail, men det var också ett arbete fyllt till brädden med glädje. Professor Watanabes studie av François Rabelais utgör sålunda en av de mest framstående och fruktbara vetenskapliga prestationerna i Japans intellektuella värld.

Watanabe studerade i Paris före andra världskriget. När han berättade för sin akademiske handledare om sin önskan att översätta Rabelais till japanska, svarade den ansedde äldre franske forskaren den ambitiöse unge japanske studenten med orden: “L’entreprise inoui’e de la traduction en Japonais de l’intraduisible Rabelais” (det exempellösa företaget att översätta den: oöversättlige Rabelais till japanska). En annan fransk forskare svarade med oförställd häpnad: “Belle entreprise Pantagruélique” (ett beundransvärt pantagrueliskt företag). Inte nog med att Watanabe trots allt detta fullföljde sitt storslagna företag under eländiga förhållanden under kriget och den amerikanska ockupationen utan han gjorde även sitt yttersta för att till dåtidens förvirrade och desorienterade Japan överflytta liv och tankar från de franska humanister som var föregångare, samtida och efterföljare till François Rabelais.

I såväl mitt liv som mitt skrivande har jag varit lärjunge till professor Watanabe. Jag påverkades av honom i två avgörande avseenden. Det ena var i min metod för romanskrivande. Av hans Rabelais-översättning lärde jag mig i konkret form det som Michail Bachtin formulerade som “den groteska realismens bildsystem eller det folkliga skrattets kultur”: betydelsen av konkreta och fysiska principer; överensstämmelsen mellan kosmiska, samhälleliga och fysiska element; överlappningen mellan döden och begäret efter återfödsel; och så skrattet som undergräver hierarkiska relationer.

Bildsystemet gjorde det möjligt för mig; en person som var född och uppvuxen i en periferisk, marginell randregion i det perifera, marginella randlandet Japan, att hitta litterära metoder för att nå fram till det universella. Med en sådan bakgrund representerar jag inte Asien som en ny ekonomisk stormakt utan ett Asien som genomsyrats av ständig fattigdom och kaotisk fertilitet. Genom att vi delar gamla, välbekanta och fortfarande levande metaforer står jag på samma sida som författare som Kim Ji-ha från Korea, Chon I och Mu Jen, båda från Kina. För mig består världslitteraturens broderskap på ett konkret plan av sådana relationer. Jag har en gång deltagit i en hungerstrejk för en begåvad koreansk poets politiska frihet. Nu är jag djupt oroad för hur det har gått för de begåvade kinesiska romanförfattare som har varit berövade sin frihet ända sedan händelsen på Himmelska Fridens Torg.

Ett annat sätt på vilket professor Watanabe har påverkat mig är genom sina tankar om humanismen. Jag uppfattar den som kvintessensen av Europa som en levande helhet. Det är en tanke som även kommer till synes i Milan Kunderas definition av romanens väsen. Utgående ifrån sina omsorgsfulla studier av historiska källor skrev Watanabe analyserande biografier, med Rabelais i centrum, om olika personer från Erasmus till Sébastien Castellion och om kvinnorna runt Henrik IV från drottning Marguerite till Gabrielle Destré. Härigenom hade Watanabe för avsikt att undervisa japanerna om humanismen, om vikten av tolerans, om hur lätt människan kan ta skada av sina förutfattade meningar eller av maskiner som hon själv har skapat. Hans uppriktighet fick honom att citera yttrandet av den danske filologen Kristoffer Nyrop: “De som inte protesterar mot krig är medskyldiga till krig”. I sin strävan att till Japan överföra humanismen som utgörande själva grundvalen till västerländskt tänkande gav sig Watanabe modigt i kast med såväl l’entreprise inouïe som la belle entreprise Pantagruélique.

Påverkad som jag är av Watanabes humanism önskar jag se min uppgift som romanförfattare att ge både dem som uttrycker sig med ord och deras läsare en möjlighet att återhämta sig efter sina egna och sin tidsålders lidanden och att läka såren i sina själar. Jag sade förut att jag är splittrad mellan de båda motsatta polerna i den kluvenhet som är kännetecknande för japanerna. Med hjälp av litteraturen har jag bemödat mig om att finna bot och läkning för dessa smärtor och sår. Jag har också bemödat mig om att be för att mina japanska landsmän också de skall återhämta sig och få sina sår läkta.

Min mentalt handikappade son Hikari, om ni tillåter att jag nämner honom igen, hittade genom fågelröster fram till Bachs och Mozarts musik och började till slut komponera egna verk. De små stycken som han först komponerade var fyllda av frisk lyskraft och glädje. De liknade dagg som glittrade på grässtrån. Det engelska ordet innocence, oskuldsfullhet, är sammansatt av in “inte” och nocere “göra illa”, det vill säga “inte göra illa”. I detta hänseende blev Hikaris musik ett naturligt vidareflöde av kompositörens egen oskuldsfullhet.

Allt eftersom Hikari fortsatte att komponera fler verk kunde jag inte undgå att i hans musik också höra “rösten av en gråtande och mörk själ”. Mentalt handikappad som han var blev det hans ihärdiga möda som försåg hans komponerande eller hans “habit of life” med en ökad kompositionell teknik och en fördjupad begreppsförmåga. Detta gjorde i sin tur att han i djupet av sitt hjärta kom att upptäcka en fond av mörk sorg som han än så länge inte hade förmått identifiera med ord.

“Rösten av en gråtande och mörk själ” är vacker, och genom att ge den musikaliskt uttryck finner han bot för sin mörka sorg. Dessutom har hans musik vunnit erkännande för sin förmåga att ge bot och lindring också till hans lyssnare idag. Detta ger mig en grund för min tro på konstens utomordentliga läkekraft.

Denna min tro har inte till fullo bekräftats. Även om jag är en svag människa, “a weak person”, för att tala med Auden, skulle jag med hjälp av denna overifierbara tro vilja “suffer dully all the wrongs”, ta på mig lidandet för alla de orättfärdigheter som hopats under nittonhundratalet som ett resultat av den ohyggliga utvecklingen inom teknologi och transport. Som en människa med en periferisk, marginell rand tillvaro här i världen skulle jag vilja hitta ett sätt – ett sätt som jag hoppas blir ett anspråkslöst, anständigt och humanistiskt bidrag på vilket jag kan vara till någon liten nytta för att bringa mänskligheten bot och försoning.

Översättning från engelska: Ulla Roseen

* Manuscript version.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1994

Kenzaburo Oe – Banquet speech

Kenzaburo Oe’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1994

I am a strange Japanese who spent his infancy and boyhood under the overwhelming influence of Nils Holgersson. So great was Nils’ influence on me that there was a time I could name Sweden’s beautiful locales better than those of my own country.

Nils’ ponderous weight extended to my literary predilections. I turned a cold shoulder to “The Tale of Genji”. I felt closer to Selma Lagerlöf and respected her more than Lady Murasaki, the author of this celebrated work. However, thanks again to Nils and his friends, I have rediscovered the attraction to “The Tale of Genji”. Nils’ winged comrades carried me there.

Genji, the protagonist of the classic tale, bids a flock of geese he sees in flight to search for his wife’s departed soul which has failed to appear even in his dreams.

The destination of the soul: this is what I, led on by Nils Holgersson, came to seek in the literature of Western Europe. I fervently hope that my pursuit, as a Japanese, of literature and culture will, in some small measure, repay Western Europe for the light it has shed upon the human condition. Perhaps my winning the Prize has availed me of one such opportunity. Still, so many gifts of thought and insight keep coming, and I have hardly begun to do anything in return. This banquet, too, is another gift which I accept with deep gratitude. I thank you.

Kenzaburo Oe – Bibliography

| Works in Japanese |

| A selection of novels, short stories and essays: |

| Shisha no ogori. – Tokyo: Bungei shunju, 1958 |

| Memushiri kouchi. – Tokyo: Kodansha, 1958 |

| Miru mae ni tobe. – Tokyo: Shinchosha, 1958 |

| Nichijo seikatsu no boken. – Tokyo, 1963 |

| Kojinteki na taiken. – Tokyo: Shinchosha, 1964 |

| Hiroshima noto. – Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1965 |

| Man’en gannen no futtoboru. – Tokyo: Kodansha, 1967 |

| Warera no kyoki o iki nobiru michi o oshieyo. 1969 |

| Okinawa noto. – Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1970 |

| Shosetsu no hoho. – Tokyo: Iwanami Gendai Senso, 1978 |

| Natsukashii toshi e no tegami. – Tokyo: Kodansha, 1986 |

| M/T to mori no fushigi no monogatari. – Tokyo: Iwanami, Shoten, 1986 |

| Chiryo no to. – Tokyo, 1990 |

| Yuruyaka na kizuna. – Tokyo: Kodansha, 1996 |

| Torikaeko. – Tokyo: Kodansha, 2000 |

| Ureigao no warabe. – Tokyo: Kodansha, 2002 |

| Nihyakunen no kodomo. – Tokyo : Chūōm, 2003 |

| Sayonara, watashi no hon yo!. – Tokyo: Kodansha, 2005 |

| Suishi. – Tokyo: Kodansha, 2005 |

| Routashi Anaberu rī souke dachitu mimakaritu. – Tokyo : Shinchosha, 2007 |

| Translations into English |

| The Catch // Japan Quarterly, 6:1, 1959 |

| Lavish are the Dead // Japan Quarterly, 12:2, 1965 |

| A Personal Matter. – New York: Grove Press, 1968; London: W&N, 1969 |

| The Silent Cry. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1974; – London: Serpernt’s Tail, 1988 |

| Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness. – New York: Grove Press, 1977 ; London : Serpent’s Tail, 1989 |

| The Catch and other War Stories. – Tokyo ; New York : Kodansha International, 1981 |

| The Pinch Runner Memorandum. – New York : M.E. Sharpe, 1994 |

| Hiroshima Notes. – Tokyo : YMCA Press, 1981. Rev. ed. 1995 |

| Japan, the Ambiguous, and Myself : the Nobel Prize speech and other lectures. – Tokyo ; New York : Kodansha International, 1995 |

| Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids. – London ; New York : Marion Boyars, 1995 |

| An Echo of Heaven. – Tokyo : Kodansha International, 1996 |

| A Healing Family. – Tokyo : Kodansha International, 1996 |

| A Quiet Life. – New York : Grove Press, 1996 |

| Seventeen ; J : Two Novels. – New York : Blue Moon Books, 1996 |

| Rouse Up O Young Men of the New Age! – New York : Grove Press, 2002 |

| Somersault. – New York : Grove Press, 2003 |

| The Changeling. – New York : Grove Press, 2010 |

| Critical studies |

| Wilson, Michiko Niikuni, The marginal world of Oe Kenzaburo : a study in themes and techniques. – Armonk, N.Y. : Sharpe, 1986 |

| Oe and beyond : fiction in contemporary Japan / edited by Stephen Snyder and Philip Gabriel. – Honolulu : University of Hawai’i Press, 1999 |

| Claremont, Yasuko, The novels of Oe Kenzaburo. – London : Routledge, 2008 |

The Swedish Academy, 2013

Kenzaburo Oe – Prose

Excerpt from Prize Stock

When I woke up, fecund morning light was slanting through every crack in the slat walls, and it was already hot. My father was gone. So was his gun from the wall. I shook my brother awake and went out to the cobblestone road without a shirt. The road and the stone steps were awash in the morning light. Children squinting and blinking in the glare were standing vacantly or picking fleas out of the dogs or running around and shouting, but there were no adults. My brother and I ran over to the blacksmith’s shed in the shade of the lush nettle tree. In the darkness inside, the charcoal fire on the dirt floor spit no tongues of red flame, the bellows did not hiss, the blacksmith lifted no red-hot steel with his lean, sun-blackened arms. Morning and the blacksmith not in his shop – we had never known this to happen. Arm in arm, my brother and I walked back along the cobblestone road in silence. The village was empty of adults. The women were probably waiting at the back of their dark houses. Only the children were drowning in the flood of sunlight. My chest tightened with anxiety.

Harelip spotted us from where he was sprawled at the stone steps that descended to the village fountain and came running over, arms waving. He was working hard at being important, spraying fine white bubbles of sticky saliva from the split in his lip.

“Hey! Have you heard?” he shouted, slamming me on the shoulder.

“Have you?”

“Heard?” I said vaguely.

“That plane yesterday crashed in the hills last night. And they’re looking for the enemy soldiers that were in it, the adults have all gone hunting in the hills with their guns!”

“Will they shoot the enemy soldiers?” my brother asked shrilly.

“They won’t shoot, they don’t have much ammunition,” Harelip explained obligingly, “They aim to catch them!”

“What do you think happened to the plane?” I said.

“It got stuck in the fir trees and came apart,” Harelip said quickly, his eyes flashing. “The mailman saw it, you know those trees.”

I did, fir blossoms like grass tassles would be in bloom in those woods now. And at the end of summer, fir cones shaped like wild bird eggs would replace the tassles, and we would collect them to use as weapons. At dusk then and at dawn, with a sudden rude clatter, the dark brown bullets would be fired into the walls of the storehouse. . . .

“Do you know the woods I mean?”

“Sure I do. Want to go?”

Harelip smiled slyly, countless wrinkles forming around his eyes, and peered at me in silence. I was annoyed.

“If we’re going to to go I’ll get a shirt,” I said, glaring at Harelip. “And don’t try leaving ahead of me because I’ll catch up with you right away!”

Harelip’s whole face became a smirk and his voice was fat with satisfaction.

“Nobody’s going! Kids are forbidden to go into the hills. You’d be mistaken for the foreign soldiers and shot!”

I hung my head and stared at my bare feet on the cobblestones baking in the morning sun, at the sturdy, stubby toes. Disappointment seeped through me like treesap and made my skin flush hot as the innards of a freshly killed chicken.

“What do you think the enemy looks like?” my brother said.

Excerpt from the short story “Prize Stock” from Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness : four short novels by Kenzaburo Oe

Translated by John Nathan

Published by Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd., London, 1989

Translation copyright © 1977 by John Nathan

ISBN: 0-7145-3048-4

Reprinted by arrangement with Marion Boyars Publishers

Excerpt selected by the Nobel Library of the Swedish Academy.

Kenzaburo Oe – Nobel Lecture

English

Swedish

Japanese (pdf)*

Nobel Lecture, December 7, 1994

Japan, The Ambiguous, and Myself

During the last catastrophic World War I was a little boy and lived in a remote, wooded valley on Shikoku Island in the Japanese Archipelago, thousands of miles away from here. At that time there were two books by which I was really fascinated: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Wonderful Adventures of Nils. The whole world was then engulfed by waves of horror. By reading Huckleberry Finn I felt I was able to justify my act of going into the mountain forest at night and sleeping among the trees with a sense of security which I could never find indoors. The protagonist of The Adventures of Nils is transformed into a little creature, understands birds’ language and makes an adventurous journey. I derived from the story sensuous pleasures of various kinds. Firstly, living as I was in a deep wood on the Island of Shikoku just as my ancestors had done long ago, I had a revelation that this world and this way of life there were truly liberating. Secondly, I felt sympathetic and identified myself with Nils, a naughty little boy, who while traversing Sweden, collaborating with and fighting for the wild geese, transforms himself into a boy, still innocent, yet full of confidence as well as modesty. On coming home at last, Nils speaks to his parents. I think that the pleasure I derived from the story at its highest level lies in the language, because I felt purified and uplifted by speaking along with Nils. His worlds run as follows (in French and English translation):

“Maman, Papa! Je suis grand, je suis de nouveau un homme!” cria-t-il.

“Mother and father!” he cried. “I’m a big boy. I’m a human being again!”

I was fascinated by the phrase ‘je suis de nouveau un homme!’ in particular. As I grew up, I was continually to suffer hardships in different realms of life – in my family, in my relationship to Japanese society and in my way of living at large in the latter half of the twentieth century. I have survived by representing these sufferings of mine in the form of the novel. In that process I have found myself repeating, almost sighing, ‘je suis de nouveau un homme!’ Speaking like this as regards myself is perhaps inappropriate to this place and to this occasion. However, please allow me to say that the fundamental style of my writing has been to start from my personal matters and then to link it up with society, the state and the world. I hope you will forgive me for talking about my personal matters a little further.

Half a century ago, while living in the depth of that forest, I read The Adventures of Nils and felt within it two prophecies. One was that I might one day become able to understand the language of birds. The other was that I might one day fly off with my beloved wild geese – preferably to Scandinavia.

After I got married, the first child born to us was mentally handicapped. We named him Hikari, meaning ‘Light’ in Japanese. As a baby he responded only to the chirps of wild birds and never to human voices. One summer when he was six years old we were staying at our country cottage. He heard a pair of water rails (Rallus aquaticus) warbling from the lake beyond a grove, and he said with the voice of a commentator on a recording of wild birds: “They are water rails”. This was the first moment my son ever uttered human words. It was from then on that my wife and I began having verbal communication with our son.

Hikari now works at a vocational training centre for the handicapped, an institution based on ideas we learnt from Sweden. In the meantime he has been composing works of music. Birds were the originators that occasioned and mediated his composition of human music. On my behalf Hikari has thus accomplished the prophecy that I might one day understand the language of birds. I must say also that my life would have been impossible but for my wife with her abundant female force and wisdom. She has been the very incarnation of Akka, the leader of Nils’s wild geese. Together with her I have flown to Stockholm and the second of the prophecies has also, to my utmost delight, now been realised.

Kawabata Yasunari, the first Japanese writer who stood on this platform as a winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, delivered a lecture entitled Japan, the Beautiful, and Myself. It was at once very beautiful and vague. I have used the English word vague as an equivalent of that word in Japanese aimaina. This Japanese adjective could have several alternatives for its English translation. The kind of vagueness that Kawabata adopted deliberately is implied in the title itself of his lecture. It can be transliterated as ‘myself of beautiful Japan’. The vagueness of the whole title derives from the Japanese particle ‘no’ (literally ‘of’) linking ‘Myself’ and ‘Beautiful Japan’.

The vagueness of the title leaves room for various interpretations of its implications. It can imply ‘myself as a part of beautiful Japan’, the particle ‘no’ indicating the relationship of the noun following it to the noun preceding it as one of possession, belonging or attachment. It can also imply ‘beautiful Japan and myself’, the particle in this case linking the two nouns in apposition, as indeed they are in the English title of Kawabata’s lecture translated by one of the most eminent American specialists of Japanese literature. He translates ‘Japan, the beautiful and myself’. In this expert translation the traduttore (translator) is not in the least a traditore (betrayer).

Under that title Kawabata talked about a unique kind of mysticism which is found not only in Japanese thought but also more widely Oriental thought. By ‘unique’ I mean here a tendency towards Zen Buddhism. Even as a twentieth-century writer Kawabata depicts his state of mind in terms of the poems written by medieval Zen monks. Most of these poems are concerned with the linguistic impossibility of telling truth. According to such poems words are confined within their closed shells. The readers can not expect that words will ever come out of these poems and get through to us. One can never understand or feel sympathetic towards these Zen poems except by giving oneself up and willingly penetrating into the closed shells of those words.

Why did Kawabata boldly decide to read those extremely esoteric poems in Japanese before the audience in Stockholm? I look back almost with nostalgia upon the straightforward bravery which he attained towards the end of his distinguished career and with which he made such a confession of his faith. Kawabata had been an artistic pilgrim for decades during which he produced a host of masterpieces. After those years of his pilgrimage, only by making a confession as to how he was fascinated by such inaccessible Japanese poems that baffle any attempt fully to understand them, was he able to talk about ‘Japan, the Beautiful, and Myself’, that is, about the world in which he lived and the literature which he created.

It is noteworthy, furthermore, that Kawabata concluded his lecture as follows:

My works have been described as works of emptiness, but it is not to be taken for the nihilism of the West. The spiritual foundation would seem to be quite different. Dogen entitled his poem about the seasons ‘Innate Reality’, and even as he sang of the beauty of the seasons he was deeply immersed in Zen.

(Translation by Edward Seidensticker)

Here also I detect a brave and straightforward self-assertion. On the one hand Kawabata identifies himself as belonging essentially to the tradition of Zen philosophy and aesthetic sensibilities pervading the classical literature of the Orient. Yet on the other he goes out of his way to differentiate emptiness as an attribute of his works from the nihilism of the West. By doing so he was whole-heartedly addressing the coming generations of mankind with whom Alfred Nobel entrusted his hope and faith.

To tell you the truth, rather than with Kawabata my compatriot who stood here twenty-six years ago, I feel more spiritual affinity with the Irish poet William Butler Yeats who was awarded a Nobel Prize for Literature seventy one years ago when he was at about the same age as me. Of course I would not presume to rank myself with the poetic genius Yeats. I am merely a humble follower living in a country far removed from his. As William Blake, whose work Yeats revalued and restored to the high place it holds in this century, once wrote: ‘Across Europe & Asia to China & Japan like lightnings’.

During the last few years I have been engaged in writing a trilogy which I wish to be the culmination of my literary activities. So far the first two parts have been published and I have recently finished writing the third and final part. It is entitled in Japanese A Flaming Green Tree. I am indebted for this title to a stanza from Yeats’s poem Vacillation:

A tree there is that from its topmost bough

Is half all glittering flame and half all green

Abounding foliage moistened with the dew …

(‘Vacillation’, 11-13)

In fact my trilogy is so soaked in the overflowing influence of Yeats’s poems as a whole. On the occasion of Yeat’s winning the Nobel Prize the Irish Senate proposed a motion to congratulate him, which contained the following sentences:

… the recognition which the nation has gained, as a prominent contributor to the world’s culture, through his success.”

… a race that hitherto had not been accepted into the comity of nations.

… Our civilization will be assesed on the name of Senator Yeats.

… there will always be the danger that there may be a stampeding of people who are sufficiently removed from insanity in enthusiasm for destruction.

(The Nobel Prize: Congratulations to Senator Yeats)

Yeats is the writer in whose wake I would like to follow. I would like to do so for the sake of another nation that has now been ‘accepted into the comity of nations’ but rather on account of the technology in electrical engineering and its manufacture of automobiles. Also I would like to do so as a citizen of such a nation which was stamped into ‘insanity in enthusiasm of destruction’ both on its own soil and on that of the neighbouring nations.

As someone living in the present would such as this one and sharing bitter memories of the past imprinted on my mind, I cannot utter in unison with Kawabata the phrase ‘Japan, the Beautiful and Myself’. A moment ago I touched upon the ‘vagueness’ of the title and content of Kawabata’s lecture. In the rest of my lecture I would like to use the word ‘ambiguous’ in accordance with the distinction made by the eminent British poet Kathleen Raine; she once said of William Blake that he was not so much vague as ambiguous. I cannot talk about myself otherwise than by saying ‘Japan, the Ambiguous, and Myself’.

My observation is that after one hundred and twenty years of modernisation since the opening of the country, present-day Japan is split between two opposite poles of ambiguity. I too am living as a writer with this polarisation imprinted on me like a deep scar.

This ambiguity which is so powerful and penetrating that it splits both the state and its people is evident in various ways. The modernisation of Japan has been orientated toward learning from and imitating the West. Yet Japan is situated in Asia and has firmly maintained its traditional culture. The ambiguous orientation of Japan drove the country into the position of an invader in Asia. On the other hand, the culture of modern Japan, which implied being thoroughly open to the West or at least that impeded understanding by the West. What was more, Japan was driven into isolation from other Asian countries, not only politically but also socially and culturally.

In the history of modern Japan literature the writers most sincere and aware of their mission were those ‘post-war writers’ who came onto the literary scene immediately after the last War, deeply wounded by the catastrophe yet full of hope for a rebirth. They tried with great pains to make up for the inhuman atrocities committed by Japanese military forces in Asian countries, as well as to bridge the profound gaps that existed not only between the developed countries of the West and Japan but also between African and Latin American countries and Japan. Only by doing so did they think that they could seek with some humility reconciliation with the rest of the world. It has always been my aspiration to cling to the very end of the line of that literary tradition inherited from those writers.

The contemporary state of Japan and its people in their post – modern phase cannot but be ambivalent. Right in the middle of the history of Japan’s modernisation came the Second World War, a war which was brought about by the very aberration of the modernisation itself. The defeat in this War fifty years ago occasioned an opportunity for Japan and the Japanese as the very agent of the War to attempt a rebirth out of the great misery and sufferings that were depicted by the ‘Post-war School’ of Japanese writers. The moral props for Japanese aspiring to such a rebirth were the idea of democracy and their determination never to wage a war again. Paradoxically, the people and state of Japan living on such moral props were not innocent but had been stained by their own past history of invading other Asian countries. Those moral props mattered also to the deceased victims of the nuclear weapons that were used for the first time in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and for the survivors and their off-spring affected by radioactivity (including tens of thousands of those whose mother tongue is Korean).

In the recent years there have been criticisms levelled against Japan suggesting that she should offer more military forces to the United Nations forces and thereby play a more active role in the keeping and restoration of peace in various parts of the world. Our heart sinks whenever we hear these criticisms. After the end of the Second World War it was a categorical imperative for us to declare that we renounced war forever in a central article of the new Constitution. The Japanese chose the principle of eternal peace as the basis of morality for our rebirth after the War.

I trust that the principle can best be understood in the West with its long tradition of tolerance for conscientious rejection of military service. In Japan itself there have all along been attempts by some to obliterate the article about renunciation of war from the Constitution and for this purpose they have taken every opportunity to make use of pressures from abroad. But to obliterate from the Constitution the principle of eternal peace will be nothing but an act of betrayal against the peoples of Asia and the victims of the Atom Bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It is not difficult for me as a writer to imagine what would be the outcome of that betrayal.

The pre-war Japanese Constitution that posited an absolute power transcending the principle of democracy had sustained some support from the populace. Even though we now have the half-century-old new Constitution, there is a popular sentiment of support for the old one that lives on in reality in some quarters. If Japan were to institutionalise a principle other than the one to which we have adhered for the last fifty years, the determination we made in the post-war ruins of our collapsed effort at modernisation – that determination of ours to establish the concept of universal humanity would come to nothing. This is the spectre that rises before me, speaking as an ordinary individual.

What I call Japan’s ‘ambiguity’ in my lecture is a kind of chronic disease that has been prevalent throughout the modern age. Japan’s economic prosperity is not free from it either, accompanied as it is by all kinds of potential dangers in the light of the structure of world economy and environmental conservation. The ‘ambiguity’ in this respect seems to be accelerating. It may be more obvious to the critical eyes of the world at large than to us within the country. At the nadir of the post-war economic poverty we found a resilience to endure it, never losing our hope for recovery. It may sound curious to say so, but we seem to have no less resilience to endure our anxiety about the ominous consequence emerging out of the present prosperity. From another point of view, a new situation now seems to be arising in which Japan’s prosperity is going to be incorporated into the expanding potential power of both production and consumption in Asia at large.

I am one of the writers who wish to create serious works of literature which dissociate themselves from those novels which are mere reflections of the vast consumer cultures of Tokyo and the subcultures of the world at large. What kind of identity as a Japanese should I seek? W.H. Auden once defined the novelist as follows:

…, among the dust

Be just, among the Filthy filthy too,

And in his own weak person, if he can,

Must suffer dully all the wrongs of Man.

(‘The Novelist’, 11-14)

This is what has become my ‘habit of life’ (in Flannery O’Connor’s words) through being a writer as my profession.

To define a desirable Japanese identity I would like to pick out the word ‘decent’ which is among the adjectives that George Orwell often used, along with words like ‘humane’, ‘sane’ and ‘comely’, for the character types that he favoured. This deceptively simple epithet may starkly set off and contrast with the word ‘ambiguous’ used for my identification in ‘Japan, the Ambiguous, and Myself’. There is a wide and ironical discrepancy between what the Japanese seem like when viewed from outside and what they wish to look like.

I hope Orwell would not raise an objection if I used the word ‘decent’ as a synonym of ‘humanist’ or ‘humaniste’ in French, because both words share in common qualities such as tolerance and humanity. Among our ancestors were some pioneers who made painstaking efforts to build up the Japanese identity as ‘decent’ or ‘humanist’.

One such person was the late Professor Kazuo Watanabe, a scholar of French Renaissance literature and thought. Surrounded by the insane ardour of patriotism on the eve and in the middle of the Second World War, Watanabe had a lonely dream of grafting the humanist view of man on to the traditional Japanese sense of beauty and sensitivity to Nature, which fortunately had not been entirely eradicated. I must hasten to add that Professor Watanabe had a conception of beauty and Nature different from that conceived of by Kawabata in his ‘Japan, the Beautiful, and Myself. ‘

The way Japan had tried to build up a modern state modelled on the West was cataclysmic. In ways different from, yet partly corresponding to, that process Japanese intellectuals had tried to bridge the gap between the West and their own country at its deepest level. It must have been a laborious task or travail but it was also one that brimmed with joy. Professor Watanabe’s study of François Rabelais was thus one of the most distinguished and rewarding scholarly achievements of the Japanese intellectual world.

Watanabe studied in Paris before the Second World War. When he told his academic supervisor about his ambition to translate Rabelais into Japanese, the eminent elderly French scholar answered the aspiring young Japanese student with the phrase: “L’entreprise inouie de la traduction de l’intraduisible Rabelais” (the unprecedented enterprise of translating into Japanese untranslatable Rabelais). Another French scholar answered with blunt astonishment: “Belle entreprise Pantagruélique” (an admirably Pantagruel-like enterprise). In spite of all this not only did Watanabe accomplish his great enterprise in a poverty-stricken environment during the War and the American Occupation, but he also did his best to transplant into the confused and disorientated Japan of that time the life and thought of those French humanists who were the forerunners, contemporaries and followers of François Rabelais.

In both my life and writing I have been a pupil of Professor Watanabe’s. I was influenced by him in two crucial ways. One was in my method of writing novels. I learnt concretely from his translation of Rabelais what Mikhail Bakhtin formulated as ‘the image system of grotesque realism or the culture of popular laughter’; the importance of material and physical principles; the correspondence between the cosmic, social and physical elements; the overlapping of death and passions for rebirth; and the laughter that subverts hierarchical relationships.

The image system made it possible to seek literary methods of attaining the universal for someone like me born and brought up in a peripheral, marginal, off-centre region of the peripheral, marginal, off-centre country, Japan. Starting from such a background I do not represent Asia as a new economic power but an Asia impregnated with ever-lasting poverty and a mixed-up fertility. By sharing old, familiar yet living metaphors I align myself with writers like Kim Ji-ha of Korea, Chon I and Mu Jen, both of China. For me the brotherhood of world literature consists in such relationships in concrete terms. I once took part in a hunger strike for the political freedom of a gifted Korean poet. I am now deeply worried about the destiny of those gifted Chinese novelists who have been deprived of their freedom since the Tienanmen Square incident.

Another way in which Professor Watanabe has influenced me is in his idea of humanism. I take it to be the quintessence of Europe as a living totality. It is an idea which is also perceptible in Milan Kundera’s definition of the spirit of the novel. Based on his accurate reading of historical sources Watanabe wrote critical biographies, with Rabelais at their centre, of people from Erasmus to Sébastien Castellion, and of women connected with Henri IV from Queen Marguerite to Gabrielle Destré. By doing so Watanabe intended to teach the Japanese about humanism, about the importance of tolerance, about man’s vulnerability to his preconceptions or machines of his own making. His sincerity led him to quote the remark by the Danish philologist Kristoffer Nyrop: “Those who do not protest against war are accomplices of war.” In his attempt to transplant into Japan humanism as the very basis of Western thought Watanabe was bravely venturing on both “l’entreprise inouïe” and the “belle entreprise Pantagruélique”.

As someone influenced by Watanabe’s humanism I wish my task as a novelist to enable both those who express themselves with words and their readers to recover from their own sufferings and the sufferings of their time, and to cure their souls of the wounds. I have said I am split between the opposite poles of ambiguity characteristic of the Japanese. I have been making efforts to be cured of and restored from those pains and wounds by means of literature. I have made my efforts also to pray for the cure and recovery off my fellow Japanese.

If you will allow me to mention him again, my mentally handicapped son Hikari was awakened by the voices of birds to the music of Bach and Mozart, eventually composing his own works. The little pieces that he first composed were full of fresh splendour and delight. They seemed like dew glittering on grass leaves. The word innocence is composed of in – ‘not’ and nocere – ‘hurt’, that is, ‘not to hurt’. Hikari’s music was in this sense a natural effusion of the composer’s own innocence.

As Hikari went on to compose more works, I could not but hear in his music also ‘the voice of a crying and dark soul’. Mentally handicapped as he was, his strenuous effort furnished his act of composing or his ‘habit of life’ with the growth of compositional techniques and a deepening of his conception. That in turn enabled him to discover in the depth of his heart a mass of dark sorrow which he had hitherto been unable to identify with words.

‘The voice of a crying and dark soul’ is beautiful, and his act of expressing it in music cures him of his dark sorrow in an act of recovery. Furthermore, his music has been accepted as one that cures and restores his contemporary listeners as well. Herein I find the grounds for believing in the exquisite healing power of art.

This belief of mine has not been fully proved. ‘Weak person’ though I am, with the aid of this unverifiable belief, I would like to ‘suffer dully all the wrongs’ accumulated throughout the twentieth century as a result of the monstrous development of technology and transport. As one with a peripheral, marginal and off-centre existence in the world I would like to seek how – with what I hope is a modest decent and humanist contribution – I can be of some use in a cure and reconciliation of mankind.

* Manuscript version.

Kenzaburo Oe – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Kenzaburo Oe from Pegasos Author’s Calendar

Video

‘Conversations with History: Kenzaburo Oe’ from University of California Television (UCTV)

Kenzaburo Oe – Facts

Kenzaburo Oe – Biographical

Kenzaburo Oe was born in 1935, in a village hemmed in by the forests of Shikoku, one of the four main islands of Japan. His family had lived in the village tradition for several hundred years, and no one in the Oe clan had ever left the village in the valley. Even after Japan embarked on modernization soon after the Meiji Restoration, and it became customary for young people in the provinces to leave their native place for Tokyo or the other large cities, the Oes remained in Ose-mura. Maps no longer show the small hamlet by name because it was annexed by a neighbouring town. The women of the Oe clan had long assumed the role of storytellers and had related the historical events of the region, including the two uprisings that occurred there before and after the Meiji Restoration. They also told of events closer in nature to legend than to history. These stories, of a unique cosmology and of the human condition therein, which Oe heard told since his infancy, left him with an indelible mark.

The Second World War broke out when Oe was six. Militaristic education extended to every nook and cranny of the country, the Emperor as both monarch and deity reigning over its politics and its culture. Young Oe, therefore, experienced the nation’s myth and history as well as those of the village tradition, and these dual experiences were often in conflict. Oe’s grandmother was a critical storyteller who defended the culture of the village, narrating to him humourously, but ever defiantly, anti-national stories. After his father’s death during the war, his mother took over his father’s role as educator. The books she bought him – The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Strange Adventures of Nils Holgersson – have left him with an impression he says ‘he will carry to the grave’.

Japan’s defeat in the war in 1945 brought enormous change, even to the remote forest village. In schools, children were taught democratic principles, replacing those of the absolutist Emperor system, and this education was all the more thorough, for the nation was then under the administration of American and other forces. Young Oe took democracy straight to his heart. So strong was his desire for democracy that he decided to leave for Tokyo; leave the village of his forefathers, the life they had lived and preserved, out of sheer belief that the city offered him an opportunity to knock on the door of democracy, the door that would lead him to a future of freedom on paths that stretched out to the world. Had it not been for the drastic change the nation underwent at this time, Oe, whose love of trees is one of his innate qualities, would have remained in his village as his forefathers had done, and tended to the forest as one of its guardians.

At the age of eighteen, Oe made his first long train trip to Tokyo, and in the following year enrolled in the Department of French Literature at Tokyo University where he received instruction under the tutelage of Professor Kazuo Watanabe, a specialist on Francois Rabelais. Rabelais’ image system of grotesque realism, to use Mikhail Bakhtin’s terminology, provided him with a methodology to positively and thoroughly reassess the myths and history of his native village in the valley.

Watanabe’s thoughts on humanism, which he arrived at from his study of the French Renaissance, helped shape Oe’s fundamental view of society and the human condition. An avid reader of contemporary French and American literature, Oe viewed the social condition of the metropolis in light of the works he read. Yet, he also endeavored to reorganize, under the light of Rabelais and humanism, his thoughts on what the women of the village had handed down to him, those stories that constituted his background. In this sense, he was again living another duality.

Oe started writing in 1957, while still a French literature student at the university. His works from 1957 through 1958 – from the short story, The Catch, which won him the Akutagawa Award, to his first novel, Bud-Nipping, Lamb Shooting* (1958) – depict the tragedy of war tearing asunder the idyllic life of a rural youth. In Lavish are the Dead (1957), a short story, and in The Youth Who Came Late* (1961), a novel, Oe portrayed student life in Tokyo, a city where the dark shadows of the U.S. occupation still remained. Apparent in these works are strong influences of Jean-Paul Sartre and other modern French writers.

Crisis struck Oe’s life and literature with the birth of his first son, Hikari. Hikari was born with a cranial deformity resulting in his becoming a mentally- handicapped person. Traumatic as the experience was for Oe, the crisis granted him a new lease on both his life and his literature. Overcoming the agony and determined to coexist with the child, Oe wrote A Personal Matter (1964), his penning of his pain in accepting the brain-damaged child into his life, and of how he arrived at his resolve to live with him. Through the catalytic medium of humanism, he conjoined his own fate of having to accept a handicapped child into the family with that of the stance one ought to take in contemporary society, and wrote Hiroshima Notes (1965), a long essay which describes the realities and thoughts of the A-bomb victims.

Following this, Oe deepened his interest in Okinawa, the southernmost group of islands in Japan. Before the Meiji Restoration, Okinawa was an independent country with its own culture. During World War II, the islands became the site of the only battle Japan fought on its own soil. After the war, the people of Okinawa were left to suffer a long U.S. military occupation. Oe’s interest in Okinawa was oriented, politically, toward the lives of the Okinawans living on what became a U.S. military base, and, culturally, to what Okinawa meant to him in terms of its traditions. The latter opened out to a broadened interest in the culture of South Koreans, enabling him to further appreciate the importance of Japan’s peripheral cultures, which differed from Tokyo-centered culture. This pursuit provided realistic substance to his study of Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory regarding a people’s culture which led him to write The Silent Cry (1967), a work that ties in the myths and history of the forest village with the contemporary age.

After The Silent Cry, two streams of thought, which at times flow as one, are apparent and consistent in Oe’s literary world. Starting with A Personal Matter is one group of works that depicts his life of coexistence with his mentally-handicapped son, Hikari. Teach Us to Outgrow our Madness (1969), a two-volume work, painfully portrays both the agony-laden trials and errors he experiences in his life with his yet unspeaking infant child, and his pursuit of his father he lost during the war. My Deluged Soul* (1973) depicts a father who relates to his infant child who, through the medium of the songs of the wild birds, has started to communicate with the family, and who empathizes with youths that belong to a belligerent and radical political party. Rouse Up, O, Young Men of the New Age!* (1983), a work in which Oe draws upon images from William Blake’s Prophecies, depicts his son Hikari’s development from a child to a young man, and thus crowns the works he wrote about his handicapped child.

The second group are stories in which Oe relates characters who he establishes in the theater of the myths and history of his native forest village, but who interact closely with life in today’s cities. This world of Oe’s fiction, starting with Bud- Nipping, Lamb-Shooting and followed by The Silent Cry, came to shape the core of his entire literature. Making full use of new ideas of cultural anthropology, these works represent the totality of Oe’s world of fiction, as evidenced in Letters to My Sweet Bygone Years (1987), a work about a young man who, banking on his cosmology and world-view of Dante, strives but fails to establish a politico- cultural base in the forest. Contemporary Games is a story that alternates between myth and history, which Oe supports with the matriarch and trickster principles he draws from cultural anthropology. He rewrote this work in narrative form as M/T and the Wonders of the Forest* (1986). With the aid of W.B. Yeat’s poetic metaphors, Oe embarked on writing The Flaming Green Tree*, a trilogy comprised of Until the ‘Savior’ Gets Socked* (1993), Vacillating* (1994), and On The Great Day* (1995). Oe has announced that with the completion of this trilogy, he will enter into his life’s final stage of study, in which he will attempt a new form of literature. The implication of this project is that Oe deems his effort at presenting his cosmology, history and folk legend as having been brought to full circle, and that he has succeeded in creating, through his portrayal of that place in the valley and its people, a model for this contemporary age. It also implies that he considers Hikari’s becoming a composer, in actuality, surpasses the importance of his own literature about him.

Oe’s winning the Nobel Prize for 1994 has thus encouraged him to embark on his pursuit of a new form of literature and a new life for himself.

*Tentative English titles.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Kenzaburo Oe died on 3 March 2023.

Kenzaburo Oe: Laughing Prophet and Soulful Healer

Kenzaburo Oe: Laughing Prophet and Soulful Healer

by Michiko Niikuni Wilson*

This article was published on 26 January 2007.

Kenzaburo Oe, Japan’s second Nobel Laureate in Literature, with his insistence on engaging the reader in a provocative dialogue on the human condition, is one of the most impassioned voices of conscience countering the country’s minimalist cultural tradition that puts imagery and aesthetics of silence above social and political concerns.

Filtering the intellectual and cultural legacy of the Western world, his works probe the vital connection between the socio-political and the personal in a style imbued with the imaginative power of the oral tradition of his birthplace and bursting with the explosive energies of Bakhtinian grotesque realism. His aberrant images, reminiscent of Gaston Bachelard’s definition of imagination, stud complex multi-layered narratives, in which the diverse voices of his characters resonate with one another within and between reinvented texts. Both conceptually and stylistically, Oe has delivered modern Japanese literature out of its long isolation and into the heart of world literature.

The Absolute Father: Ambiguous Lessons of Japan’s Past

The moral trajectory of Oe’s literary odyssey was determined by the contradictions inherent in Japan’s defeat in the Pacific War and the underlying ideology of the Emperor system that enabled it. His lifelong ambivalence regarding the ‘father image’ is rooted in this prewar ideological indoctrination centered on the divine Emperor who neither saw, heard, nor spoke to his loyal subjects. From 1931 onward, Japan pursued totalitarianism and military expansionism in the name of the Emperor: the takeover of Manchuria, the invasion of China proper, aggression toward Europe’s Asian colonies, and the attack on Pearl Harbor. As required by the imperial education edict, Oe and the other schoolchildren in the village were asked on a daily basis, “If the Emperor commands you to die, what will you do?” The expected reply was, “I will cut open my belly and die.” Although no less patriotic than his classmates, Oe was so traumatized by this forced ritual that he often could not utter a word, inviting severe beatings from his teacher. Yet on August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito spoke in a human voice and made two unthinkable radio announcements: Japan’s unconditional surrender and the renunciation of his divinity. Overnight the nation recanted the cultural-political ideology imposed on its people. Earlier, when his two older brothers were mobilized for the war effort, the nine-year-old Oe had become the family’s de facto eldest son. In 1944 he lost both his father and grandmother. On the night of his father’s sudden death, perhaps already in thrall to his sense of ambiguity about male authority figures, Oe disobeyed his mother’s order to shout as hard as he could to call back his father’s soul. The memory of her icy glare and harsh words of disapproval haunted him for almost a decade.

Japan’s surrender released conflicting emotions that began to grow and take deep root in Oe: a sense of both humiliation/subjugation and liberation/renewal. The democratic principles in Japan’s new Constitution were to become central to his humanist beliefs, but at the same time everything taught in school about the divine father had been proven to be a lie. He had once believed in the intoxicating absolutism of the living god, but adults had betrayed him. Moreover after the surrender, the Emperor neither disavowed the disastrous direction Japan had taken, nor acknowledged the nation’s atrocities, and the United States insisted that he should not be held accountable for any of Japan’s war crimes. Many of Oe’s works are energized by this sense of contradiction, fueled, in John Nathan’s words, by an energy “that arcs between the poles of anger and longing.” [1] This ambiguity is so much the hallmark of Oe’s work that he would later entitle his Nobel Lecture, ‘Japan, the Ambiguous and Myself,’ consciously differentiating himself from Japan’s only other Nobel Laureate in Literature, Yasunari Kawabata, whose 1968 Nobel Lecture was entitled ‘Japan, the Beautiful and Myself.’

Oe’s Early Life and Literary Debut

Before the reality of wartime Japan was thrust upon him, Oe’s life had had an idyllic beginning. He was born in 1935 in Ôse village, the third of eight children, in a valley nestled deep in the lush forest of central Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands. He learned the art of storytelling from his grandmother and mother, master raconteurs and repositories of the oral tradition of this remote region. His father was a wholesale supplier of raw materials for banknote paper, and a year before his death, over a cup of sake after the end of the day, would often speak to the young son kneeling at his feet about how much he regretted being a local merchant and living a life devoid of mental stimulus. He repeatedly instructed his son to get an education. [2]

Oe was the only sibling in his family to receive a college degree. Although he loved science and mathematics, he nonetheless chose French as his major, specializing in Sartre and French humanism at Tokyo University under the tutelage of Kazuo Watanabe, Japan’s foremost expert on sixteenth-century writer François Rabelais. Soon after his admission to the University in 1954, Oe began to submit stories to the All-Japan Student Fiction Contest, for which he twice received honorable mention. Then in 1957, A Strange Job [3] won the University’s prestigious May Festival Prize, and the following year, Prize Stock [4] was given the coveted Akutagawa Prize, establishing Oe as the most innovative writer of the young generation. Set in a village community, whose bucolic life is abruptly disrupted by the war, this story introduces for the first time a pair of brothers, a young boy as the ‘older brother,’ and an infant as the ‘younger brother.’ The image of the infant as a foundling and as a hermaphrodite, who embraces the unity of opposites in his primordial state, is pivotal in Oe’s opus.

The need to remember history and to practice civil disobedience in the face of monolithic power is the basis of another powerful story from the same year, Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids. [4] Among many anecdotes Oe heard as a child from his grandmother was that of the brutal killing of a young Japanese deserter at the hands of a village mob after the futile attempt of a Korean boy to hide him. Oe expands this incident, interweaving it with the betrayal by adults of a group of reform school boys evacuated to their village during the war. In a correspondence with Günter Grass in 1995, Oe cited this story to indicate his agreement with Grass’s rhetorical question – apropos of the more than 20,000 German deserters in the Second World War put to death by military tribunals – “Weren’t they the true heroes of the war?” [6] During this same period Oe also focused on the sexual overtones and political implications of Japan’s surrender in Sheep (1958), [7] Leap Before You Look (1958), [8] and Our Times (1959). [9]

In 1960, Oe married Yukari Itami, the sister of Juzo Itami who was to become a highly successful film director. In the same year, politics intruded again into Oe’s life. Dissatisfaction with the lopsided United States–Japan power relationship came to the surface over the ratification of the United States–Japan Mutual Security Treaty, prompting the largest demonstrations in Japanese history. In a clash with the police during one of the demonstrations, a close friend of Oe’s sustained permanent brain damage and later committed suicide. The image of this tormented soul driven to suicide, takes center stage in Oe’s later narratives. Despite the highly politicized nature of his work, Oe has never belonged to a political party, nor has he been politically active apart from participating in disarmament conferences and a rally to protest the imprisonment of the Korean dissident writer Kim Chi Ha. Recent pressure from the Japanese right-wing and the United States to revise Article 9 of Japan’s Peace Constitution, which guarantees Japan’s “renunciation of war as a means of settling international disputes,” has led him and eight other ageing intellectuals to form ‘The Article 9 Society’ in order to educate the general public on its importance.

The Father with Hope in Despair

Oe’s early socio-political consciousness was to be reinforced by the birth of his first child, Hikari, in June 1963, a boy born with a defective cranium that required multiple operations. The doctor’s bleak prognosis for the newborn became fused in Oe’s mind with the image of the ‘little boy lost’ in William Blake’s Song of Innocence, in which the boy searches for a father who has abandoned him. These reflections revived images of Oe’s own traumatized childhood and the terror of the Nuclear Age, an era that began with Japan’s defeat. While his infant hovered between life and death that summer, the young father participated in the annual Peace Memorial Service for victims of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima. He returned spiritually transformed by his encounter with the survivors of the blast, who faced their agony with indomitable courage, and from conversations with Dr. Fumio Shigefuji, who counselled Oe to give in to neither hope nor despair. The father, who had assumed his son would die, saw a ray of hope for the future.