Stanley B. Prusiner – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Stanley B. Prusiner from Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases

Stanley B. Prusiner’s page at UCSF

Interview with Stanley B. Prusiner from PBS

Stanley B. Prusiner – Photo gallery

Stanley B. Prusiner receiving his Nobel Prize from the hands of His Majesty the King.

Copyright © Pica Pressfoto AB 1997, S-105 17 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46-8-13 52 40 Photo: Ulf Palm

Stanley B. Prusiner receiving his Nobel Prize.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

Stanley B. Prusiner after receiving his Nobel Prize from H.M. King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall on 10 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

Medicine laureate Stanley B. Prusiner, literature laureate Dario Fo and economic sciences laureates Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes on stage at the award ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall on 10 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

1997 Nobel Prize laureates on the Stockholm Concert Hall stage: From left: physics laureates Steven Chu, Claude Cohen-Tannoudji and William D. Phillips, chemistry laureates Paul D. Boyer, John E. Walker and Jens C. Skou, medicine laureate Stanley B. Prusiner, literature laureate Dario Fo and economic sciences laureates Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

All 1997 Nobel Laureates on the Stockholm Concert Hall stage. Stanley B. Prusiner is fourth from right.

© Pressens Bild AB, 1997 S-112 88 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46 (0)8 738 38 00. Photo: Ola Torkelsson

A view of the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 1997.

© Pica Pressfoto AB 1997, S-105 17 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46-8-13 52 40. Photo: Ulf Palm

Stanley B. Prusiner delivering his speech of thanks at the Nobel Prize banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, Sweden, on 10 December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

Stanley B. Prusiner at a press conference during Nobel Week in Stockholm, Sweden, December 1997.

Nobel Foundation. Photo: Lars Åström

Stanley B. Prusiner during a reception at the Swedish Academy during Nobel Week, December 1997

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

1997 Nobel Prize laureates assembled at the Swedish Academy in Stockholm during Nobel Week, December 10997. From left: Jens C. Skou, Stanley B. Prusiner, Steven Chu, Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

All 1997 laureates assembled at the Swedish Academy in Stockholm Sweden during Nobel Week, December 1997. Back row from left: Chemistry laureate Jens C. Skou, medicine laureate Stanley B. Prusiner, literature laureate Dario Fo, economi sciences laureates Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes. Front row from left: Chemistry laureate John E. Walker, physics laureate William D. Phillips, chemistry laureate Paul D. Boyer and physics laureate Claude Cohen-Tannoudji.

Photo from the Lars Åström archive

Stanley B. Prusiner – Curriculum Vitae

| Stanley B. Prusiner, born May 28, 1942 | |

| Address: | Department of Neurology, HSE-781, University of California, School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA 94143-0518, USA |

| Academic Education | |

| 1964 | A.B. (cum laude), University of Pennsylvania, The College |

| 1968 | M.D., University of Pennsylvania, School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA |

| 1968-69 | Internship in Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA |

| 1972-74 | Residency in Neurology, University of California, San Francisco, CA |

| Appointments and Professional Activities | |

| 1974-80 | Assistant Professor of Neurology in Residence, Univ of California, SF |

| 1976-88 | Lecturer, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, UCSF |

| 1979-83 | Assistant Professor of Virology in Residence, UC, Berkeley |

| 1980-81 | Associate Professor of Neurology in Residence, UCSF |

| 1981-84 | Associate Professor of Neurology, UCSF |

| 1983-84 | Associate Professor of Virology in Residence, UC, Berkeley |

| 1984- | Professor of Neurology, UCSF |

| 1984- | Professor of Virology in Residence, UC, Berkeley |

| 1988- | Professor of Biochemistry, UCSF |

| Major Honors and Awards |

| Potamkin Prize for Alzheimer’s Disease Research, American Academy of Neurology, 1991 |

| Christopher Columbus Quincentennial Discovery Award in Biomedical Research, NIH, 1992 Metropolitan Life Foundation Award for Medical Research, 1992 |

| Dickson Prize for Distinguished Scientific Accomplishments, University of Pittsburgh, 1992 |

| Charles A. Dana Award for Pioneering Achievements in Health, 1992 |

| Richard Lounsbery Award for Extraordinary Scientific Research, NAS, 1993 |

| Gairdner Foundation Award for Outstanding Achievement in Medical Science, 1993 |

| Bristol-Myers Squibb Award for Distinguished Achievement in Neuroscience Res., 1994 |

| Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research, Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation, 1994 |

| Paul Ehrlich Prize, Paul Ehrlich Foundation and the Federal Republic of Germany, 1995 |

| Wolf Prize in Medicine, Wolf Foundation and the State of Israel, 1996 |

| Keio International Award for Medical Science, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan, 1996 |

The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute

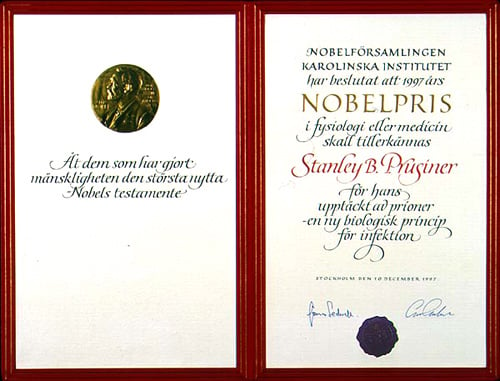

Stanley B. Prusiner – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1997

Calligrapher: Susan Duvnäs

Stanley B. Prusiner – Banquet speech

Stanley B. Prusiner’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1997

King Carl Gustaf, Queen Silvia, Distinguished Guests,

Tonight’s awarding of the Nobel Prizes and this elegant Banquet are a grand celebration of science and culture. These events honor the vision, courage, and wisdom of Alfred Nobel, a superb scientist in his own right.

And they honor the Swedish people’s uncommon sense of commitment to fulfill the enlightened wishes of Alfred Nobel – the Nobel Prizes have truly become important benchmarks in the history of science.

But the Nobel Prizes are much more than awards to scholars, they are a celebration of civilization, of mankind, and of what makes humans unique – that is their intellect from which springs creativity. I continue to be delightfully surprised by the joy, excitement, and happiness that so many of my friends and colleagues have felt when they learned of this year’s Nobel Prize in Medicine; moreover, many of these friends are nonscientists who hail from many parts of our planet.

People often ask me why I persisted in doing research on a subject that was so controversial. I frequently respond by telling them that only a few scientists are granted the great fortune to pursue topics that are so new and different that only a small number of people can grasp the meaning of such discoveries initially. I am one of those genuinely lucky scientists who was handed a special opportunity to work on such a problem – that of prions.

Because our results were so novel, my colleagues and I had great difficulty convincing other scientists of the veracity of our findings and communicating to lay people the importance of work that seemed so esoteric! As more and more compelling data accumulated, many scientists became convinced. But it was the “mad cow” epidemic in Britain and the likely transmission of bovine prions to humans producing a fatal brain illness called Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease that introduced prions to the public. Yet the principles of prion biology are still so new that some scientists and most laymen, including the press, still have considerable difficulty grasping the most fundamental concepts.

Being a scientist is a special privilege: for it brings the opportunity to be creative, the passionate quest for answers to nature’s most precious secrets, and the warm friendships of many valued colleagues. Collaborations extend far beyond the scientific achievements, no matter how great the accomplishments might be, the rich friendships which have no national borders are treasured even more.

Besides scientific achievement, the Nobel Prizes honor the scientific process. In science, each new result, sometimes quite surprising, heralds a step forward and allows one to discard some hypotheses, even though one or two of these might have been highly favored. No matter how new and revolutionary the findings may be, as data accumulates, even the skeptical scholars eventually become convinced except for a few who will always remain resistant. Indeed, the story of prions is truly an odyssey that has taken us from heresy to orthodoxy.

Lastly, we celebrate on the occasion of these Nobel Prizes, the triumph of science over prejudice. The wondrous tools of modern science allowed my colleagues and me to demonstrate that prions exist and that they are responsible for an entirely new principle of infection.

Tack så mycket!

Stanley B. Prusiner – Nobel Lecture

Stanley B. Prusiner held his Nobel Lecture on 8 December 1997, at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm. He was presented by Professor Staffan Normark, Member of the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine.

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 5.58 MB

Stanley B. Prusiner – Interview

Interview with Professor Stanley B. Prusiner by science writer Peter Sylwan, 11 December 2004.

Professor Prusiner talks about his at the time controversial discovery; the many years of work behind the Nobel Prize (2:52); his recent work (4:48); and the importance of communication between scientists and public (7:49).

Interview transcript

Welcome to meet the Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine for 1997, Dr Stanley Prusiner, the man who did as very few scientists do, but all of them will get Nobel Prizes I think, they really turn the concept we have upside down, and please tell me Dr Prusiner, what did you really turn upside down?

Stanley B. Prusiner: Im not sure I turned anything upside down, it was a discovery that people really didn’t want to accept for a long time because it went against so many preconceived notions. The idea that a protein was infectious and the disease could be both genetic and infectious and then even spontaneous. These were concepts that people had a hard time accepting.

But why was it so controversial?

Stanley B. Prusiner: I think that it was a long time in coming to understand that genes are made of DNA or RNA, primarily DNA. That all infectious agents, the progeny of all infectious agents are encoded by a strand of DNA or RNA and in fact all organisms. So, the idea that there should be something totally different and it should be “alive”, it can replicate in a biological system, just I think was very difficult to accept and I think people were justified in being sceptical because the discovery that DNA is the genetic material of life didn’t occur until the middle of the 20th century.

So in a way you challenged the central dogma of molecular biology at that time, that all the information was contained, the DNA and the RNA and the proteins were just the templates or the churning out of the … Now you’d proved that proteins in itself, in these cells right could contain information so to say?

Stanley B. Prusiner: Yes and no. In the beginning it seemed that way, that we were challenging the dogma and as the story emerged, it became very clear that it fit within the dogma of biology, but that one had to make small revisions and these revisions turned out to be groundbreaking in many other areas. The concept that a protein could then exist in two biologically active forms was not well accepted and in fact they were not good examples.

It took you 10 years to come to this conclusion, to really put forward the proofs for your idea. What kept you going when everyone was suspicious about the ideas?

… this was a 25 year project, it took me about 10 years to really get into it …

… this was a 25 year project, it took me about 10 years to really get into it …Stanley B. Prusiner: Yes, this was a 25 year project, it took me about 10 years to really get into it and lay out what I thought were the real possibilities and then another 10 years to gather the information that made it clear that these ideas were not science fiction but in fact they were real and that people who were sceptical were certainly justified but that there had now came a point where their scepticism no longer was really useful.

But what kept you going, I mean 25 years ago, tell me?

Stanley B. Prusiner: When you make a discovery like prions, you become very passionate about it and you look for other things that are as interesting, where you might not find as much human opposition and when you can’t find something, if you’re not very imaginative, you’re not very bright and you are unable to find another project that’s as exciting, then you say to yourself, well, I’ll just keep going on this and nothing better that I can work on.

But despite that all the colleagues, well not all but the scientific community around you, really thought you were doing mad things?

Stanley B. Prusiner: Not everybody, there were enough people who were very supportive and who provided the day to day support as well as being sufficiently convinced that we were doing good work to act as peers in the review of the work, so that it was supported by the National Institutes of Health, because otherwise we would have never been able to survive. In addition we had some private funding that was very important.

That is important.

Stanley B. Prusiner: Yes, the philanthropy was critical.

It’s seven year now since you came to Stockholm to get the prize and I wonder what has happened since?

Stanley B. Prusiner: My life has been a little more hectic. In some ways I’ve relaxed a little bit more, although many people would not tell you that was true and the work has continued to move forward.

Has there been any difficulties, I mean, there were controversies even when you got the prize, in the protein only had part of this work challenged for many respects and as you come up with some even more definite proof that is the protein only theory will hold?

Stanley B. Prusiner: Yes, this past summer we published two papers, one piece of work we made a synthetic prion with a peptide that we synthesised in the chemical means. This was culminated in four years of work where we’d published the first paper in the year 2000, so that was three years after the prize and then a follow-up paper this past spring. Then in the summer we published another paper in which we made the protein in bacteria and isolated the protein and then refolded it and showed that we’d made a synthetic prion that way. So we’ve done this two different ways where we’ve started with a sequence that either produced an E-coli or produced by chemical means and then changed the confirmation of the protein and turned it into an infectious pathogen.

And you proved that this synthetic infectious prion managed to alter the shape of the proteins, the prions in the infected animal?

Stanley B. Prusiner: If they didn’t do it, then I don’t know what did it.

But you were challenged on this as well, afterwards.

… even after we published these papers, we were challenged by people …

… even after we published these papers, we were challenged by people …Stanley B. Prusiner: Oh yes, even after we published these papers, we were challenged by people, not a lot, most people think that we have finished the task of convincing the world but I think, you know, there are a few, and that’s normal and they probably will never be convinced.

When you received your prize, you also gave the banquet speech where you said something like, the Nobel Prize is a celebration of science, yes and culture.

Stanley B. Prusiner: It’s a celebration of science and culture, well an intellectual achievement in our civilisation and it’s really, I think, unique. There is no other celebration like the Nobel Prize celebration.

It’s interesting, you mention science and culture together. We just got a new minister in Sweden, in science and culture, the same minister and the same department, Science and Culture, and when he gave a press conference just when he entered his chair, he didn’t get a single question on science from the journalists, just about culture.

Stanley B. Prusiner: I think that’s not surprising. I think it’s very difficult for people to ask questions about science just off the top of their heads and I think one of the problems I had with the press for so long was that they were so uneducated about science. Now to be fair to the press, they have very little time to write a story or to produce a story and so being thrown into an area where some scientists are telling them the work is excellent and others are telling them that it’s complete fraud and craziness – they don’t know how to judge. I can well imagine, when the Minister of Culture and Science is appointed and the press is asked to come to a press conference, if the press conference materials don’t lay out in detail an agenda for science, so in an understandable lay language, then I can well understand they may not ask any questions.

But maybe you could also wonder whose responsibility is this? If you want to be well known and if you want to communicate with the audience, I mean you can’t alter the journalist, the only thing you can alter is the scientist maybe, yourself.

Stanley B. Prusiner: Right, who are we talking about, the minister or myself?

Who is to blame if the communication doesn’t work, the journalists or the scientists?

… it still is the responsibility of the scientist to try to communicate better with the public …

… it still is the responsibility of the scientist to try to communicate better with the public …Stanley B. Prusiner: The scientists. I think that the scientists have to constantly try to translate what they do into language that most people can understand and we are never going to be in a position where everyone is a knowledgeable layman, meaning they have a great scientific background because whatever they learn in a university setting is already obsolete the day they graduate. So the best we can do is hope we can train them in some introductory science courses to give them a little background, but after that, it still is the responsibility of the scientist to try to communicate better with the public and this is very, very hard to do, because each year, science becomes more complicated, there’s more and more specialised vocabulary. One of the things we don’t have as scientists is we don’t have a lot of people around who understand the details of the science intimately who are interested in translating it for the public.

Because this central idea when we were talking about communication is that we talk about public understanding of science but as you phrase it now, that is not very easy to do, so maybe you should turn the thing around, it’s science understanding a public that is more interesting.

Stanley B. Prusiner: The science is understanding the public or making the scientists making science more understandable for the public.

Yes, but also to understand how the public thinks and feels and what their values are, to be able to phrase their science in a framework where people can understand it.

Stanley B. Prusiner: I think that’s very legitimate, I’m not sure how practical that is in terms of making that happen.

Do you want to try it?

Stanley B. Prusiner: I can try. Whatever you’d like to talk about, I’ll try to …

No, that in a way would be to make science as a part of culture.

Stanley B. Prusiner: I think that’s wonderful but the problem is, where do we start? How do we get this moving and it’s extremely difficult? I mean you would hope that, for instance, the web would be a great place to do this. The Internet is ideal in many respects. The problem with the Internet is there’s so much material on the Internet, it’s uncensored, it’s unreviewed, so for the person who doesn’t have a lot of knowledge, they now Google themselves into some website and all of a sudden they’re confronted with material that they can’t judge whether this material is legitimate, whether it’s reasonable, whether it fits with the scientific data or it’s some wacko person’s ideas about a disease or some physical process. You know, it’s very, very hard for people to judge this.

… you can find all kinds of material, much of which is unsupported by any scientific data …

… you can find all kinds of material, much of which is unsupported by any scientific data …I’ll give you an example in the field of mad cow disease. You can go into the Internet and look up mad cow disease and you can find all kinds of material, much of which is unsupported by any scientific data. And there are a lot of people out there interested in this because this is a huge economic issue and it’s a huge health issue and yet there’s an enormous amount of information which is available that comes from peer reviewed scientific studies and yet, if you don’t have a reasonable working knowledge, you’ll be confused when you get into this. So it’s very, very hard I think to put science out there for the public and we need to figure out how to do this. It’s not a given, in fact we do it very poorly.

But there’s a big challenge to your colleagues and for the scientific community.

Stanley B. Prusiner: I think the challenge is huge and I must say that I don’t know how to do this. I find it very difficult to identify people who are very interested in doing this. In other words, someone who has a very good working knowledge of science who can really judge and we’re not talking about all science now, we’re saying okay, someone who perhaps is very good in the field of neuroscience and neurological diseases and then finding such a person who wants to devote his or her life to making this available to the public.

Finally, what would your perspective be for the scientific community or for the society as a whole if you doesn’t succeed in communicating science?

Stanley B. Prusiner: I think that there are huge problems for society if scientists can’t communicate their science. It’s so important. Number one, funding for scientific research depends upon public support. I think that policymakers, legislators, they need to be informed and they need to be informed in terms that they can understand, not that we want them to understand, that’s number one. Secondly, I think as our planet grows more crowded, people need the information in order to make decisions that benefit others on our planet and third, if we don’t communicate science, we won’t see the science turned into technologic advantages for our civilisation.

So scientists have a huge responsibility, they’re not very good at doing this and at the same time, it’s not fair to put all the burden on them because that’s not what they want to do, that’s not the job they’ve signed up for, they’ve signed up very often to roll back the frontiers of knowledge. So we need people in between, the people gathering the knowledge, the people consuming the knowledge, we need people in between to translate and my guess is that we’re going to need to create such a discipline for our society which our society meaning civilisation on this planet, which each year grows more and more dependent upon high technology.

So, to finish, let’s hope that the audience is googling around on Google to this interview and to share the ideas and the thoughts. Thank you very much for giving us your time.

Stanley B. Prusiner: Thank you.

Thank you.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Press release

NOBELFÖRSAMLINGEN KAROLINSKA INSTITUTET

THE NOBEL ASSEMBLY AT THE KAROLINSKA INSTITUTE

6 October 1997

The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute has today decided to award the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for 1997 to

Stanley B. Prusiner

for his discovery of “Prions – a new biological principle of infection”.

Summary

The 1997 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded to the American Stanley Prusiner for his pioneering discovery of an entirely new genre of disease-causing agents and the elucidation of the underlying principles of their mode of action. Stanley Prusiner has added prions to the list of well known infectious agents including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. Prions exist normally as innocuous cellular proteins, however, prions possess an innate capacity to convert their structures into highly stabile conformations that ultimately result in the formation of harmful particles, the causative agents of several deadly brain diseases of the dementia type in humans and animals. Prion diseases may be inherited, laterally transmitted, or occur spontaneously. Regions within diseased brains have a characteristic porous and spongy appearance, evidence of extensive nerve cell death, and affected individuals exhibit neurological symptoms including impaired muscle control, loss of mental acuity, memory loss and insomnia. Stanley Prusiner’s discovery provides important insights that may furnish the basis to understand the biological mechanisms underlying other types of dementia-related diseases, for example Alzheimer’s disease, and establishes a foundation for drug development and new types of medical treatment strategies.

In 1972 Stanley Prusiner began his work after one of his patients died of dementia resulting from Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). It had previously been shown that CJD, kuru, and scrapie, a similar disease affecting sheep, could be transmitted through extracts of diseased brains. There were many theories regarding the nature of the infectious agent, including one that postulated that the infectious agent lacked nucleic acid, a sensational hypothesis since at the time all known infectious agents contained the hereditary material DNA or RNA. Prusiner took up the challenge to precisely identify the infectious agent and ten years later in 1982 he and his colleagues successfully produced a preparation derived from diseased hamster brains that contained a single infectious agent. All experimental evidence indicated that the infectious agent was comprised of a single protein, and Prusiner named this protein a prion, an acronym derived from “proteinaceous infectious particle.” It should be noted that the scientific community greeted this discovery with great skepticism, however, an unwavering Prusiner continued the arduous task to define the precise nature of this novel infectious agent.

The infectious prion particle forms within the body

Where was the gene encoding the prion, the piece of DNA that determined the sequence of the amino acids comprising the prion protein? Perhaps the gene was closely associated with the protein itself as in a small virus? The answers to these questions came in 1984 when Prusiner and colleagues isolated a gene probe and subsequently showed that the prion gene was found in all animals tested, including man. This startling finding raised even more questions. Could prions really be the causative agent of several dementia-type brain diseases when the gene was endogenous to all mammals? Prusiner must have made a mistake! The solution to this problem became evident with the sensational discovery that the prion protein, designated PrP, could fold into two distinct conformations, one that resulted in disease (scrapie PrP = PrPSc) and the other normal (PrP = PrPc). It was subsequently shown that the disease-causing prion protein had infectious properties and could initiate a chain reaction so that normal PrPc protein is converted into the more stabile PrPSc form. The PrPSc prion protein is extremely stabile and is resistant to proteolysis, organic solvents and high temperatures (even greater than 100o C). With time, non-symptomatic incubation periods vary from months to years, the disease-causing PrPSc can accumulate to levels that result in brain tissue damage. In analogy to a well known literary work, the normal PrPc can be compared to the friendly Dr. Jekyll and the disease causing PrPSc to the dangerous Mr. Hyde, the same entity but in two different manifestations.

Mutations in the prion gene cause hereditary brain diseases

The long incubation time for prion based disease hampered the initial efforts to purify the prion protein. In order to assess purification schemes Prusiner was forced to use scores of mice and in each experiment wait patiently for approximately 200 days for the appearance of disease symptoms. The purification efforts accelerated when it was demonstrated that scrapie could be transferred to hamsters, animals that exhibited markedly shortened incubation times. Together with other scientists, Prusiner cloned the prion gene and demonstrated that the normal prion protein was an ordinary component of white blood cells (lymphocytes) and was found in many other tissues as well. Normal prion proteins are particularly abundant on the surface of nerve cells in the brain. Prusiner found that the hereditary forms of prion diseases, CJD and GSS (see the last section), were due to mutations in the prion gene. Proof that these mutations caused disease was obtained when the mutant genes were introduced into the germline of mice. These transgenic mice came down with a scrapie-like disease. In 1992 prion researchers obtained conclusive evidence for the role of the prion protein in the pathogenesis of brain disease when they managed to abolish the gene encoding the prion protein in mice, creating so called prion knock-out mice. These prion knock-out mice were found to be completely resistant to infection when exposed to disease-causing prion protein preparations. Importantly, when the prion gene was reintroduced into these knock-out mice, they once again became susceptible to infection. Strangely enough, mice lacking the prion gene are apparently healthy, suggesting that the normal prion protein is not an essential protein in mice, its role in the nervous system remains a mystery.

Structural variant disease-causing prions accumulate in different regions of the brain

Specific mutations within the prion gene give rise to structurally variant disease-causing prion proteins. These structural prion variants accumulate in different regions of the brain. Dependent upon the region of the brain that becomes infected, different symptoms, typical for the particular type of disease are evident. When the cerebellum is infected the ability to coordinate body movements declines. Memory and mental acuity are affected if the cerebral cortex is infected. Thalamus specific prions disturb sleep leading to insomnia, and prions infecting the brain stem primarily affect body movement.

Other dementias may have a similar background

Prusiner’s pioneering work has opened new avenues for understanding the pathogenesis of more common dementia-type illnesses. For example, there are indications that Alzheimer’s disease is caused when certain, non-prion, proteins undergo a conformational change that leads to the formation of harmful deposits or plaques in the brain. Prusiner’s work has also established a theoretical basis for the treatment of prion diseases. It may be possible to develop pharmacological agents that prevent the conversion of harmless normal prion proteins to the disease-causing prion conformation.

Intrinsic defense mechanisms do not exist against prions

Prions are much smaller than viruses. The immune response does not react to prions since they are present as natural proteins from birth. They are not poisonous, but rather become deleterious only by converting into a structure that enables disease causing prion proteins to interact with one another forming thread-like structures and aggregates that ultimately destroy nerve cells. The mechanistic basis underlying prion protein aggregation and their cummulative destructive mechanism is still not well understood. In contrast to other infectious agents, prion particles are proteins and lack nucleic acid. The ability to transmit a prion infection from one species to another varies considerably and is dependent upon what is known as a species barrier. This barrier reflects how structurally related the prions of different species are.

Prion diseases in animals and man

Without exception, all known prion diseases lead to the death of those affected. There are, however, great variations in pre-symptomatic incubation times and how aggressively the disease progresses.

Scrapie, a prion disease of sheep, was first documented in Iceland during the 18th century. Scrapie was transferred to Scotland in the 1940s. Similar prion diseases are known to affect other animals, e.g., mink, cats, deer and moose.

Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) – Mad cow disease is a prion disease that has recently received a great deal of publicity. In England BSE was transmitted to cows through feedstuff supplemented with offals from scrapie-infected sheep. The BSE epidemic first became evident in 1985. Due to the long incubation time the epidemic did not peak until 1992. In this year alone roughly 37,000 animals were affected.

Kuru among the Fore-people in New Guinea was studied by Carleton Gajdusek (recipient of the 1976 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine). Kuru was shown to be transmitted in connection with certain cannibalistic rituals and was thought to be due to an unidentified “slow virus”. The infectious agent has now been identified as a prion. Duration of illness from first symptoms to death: 3 to 12 months.

Gertsmann-Sträussler-Scheinker (GSS) disease is a hereditary dementia resulting from a mutation in the gene encoding the human prion protein. Approximately 50 families with GSS mutations have been identified. Duration of illness from evidence of first symptoms to death: 2 to 6 years.

Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI) is due to another mutation in the gene encoding the human prion protein. Nine families have been found that carry the FFI mutation. Duration of illness from evidence of first symptoms to death: roughly one year.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) affects about one in a million people. In 85-90% of the cases it has been shown that CJD occurs spontaneously. Ten to fifteen per cent of the CJD cases are caused by mutations in the prion protein gene. In rare instances CJD is the consequence of infection. Previously infections were transmitted through growth hormone preparations prepared from the pituitary gland of infected individuals, or brain membrane transplants. About 100 families are known carriers of CJD mutations. Duration of illness from evidence of first symptoms to death: roughly one year.

A new variant of CJD that may have arisen through BSE-transmission. Since 1995 about 20 patients have been identified that exhibit CJD-like symptoms. Psychological symptoms with depression have dominated, but involuntary muscle contractions and difficulties to walk are also common.

The figure schematically illustrates how variants of disease causing prions affect different parts of the brain. In Bovine Spongiform Encephalitis (BSE), the brain stem is affected, in Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI), the thalamus region, in Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD), the cerebral cortex, while in KURU and Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker (GSS) disease the cerebellum is damaged.

Press release

NOBELFÖRSAMLINGEN KAROLINSKA INSTITUTET

THE NOBEL ASSEMBLY AT THE KAROLINSKA INSTITUTE

6 October 1997

The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute has today decided to award the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for 1997 to

Stanley B. Prusiner

for his discovery of “Prions – a new biological principle of infection”.

Summary

The 1997 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded to the American Stanley Prusiner for his pioneering discovery of an entirely new genre of disease-causing agents and the elucidation of the underlying priciples of their mode of action. Stanley Prusiner has added prions to the list of well known infectious agents including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. Prions exist normally as innocuous cellular proteins, however, prions possess an innate capacity to convert their structures into highly stabile conformations that ultimately result in the formation of harmful particles, the causative agents of several deadly brain diseases of the dementia type in humans and animals. Prion diseases may be inherited, laterally transmitted, or occur spontaneously. Regions within diseased brains have a characteristic porous and spongy appearance, evidence of extensive nerve cell death, and affected individuals exhibit neurological symptoms including impaired muscle control, loss of mental acuity, memory loss and insomnia. Stanley Prusiner’s discovery provides important insights that may furnish the basis to understand the biological mechanisms underlying other types of dementia-related diseases, for example Alzheimer’s disease, and establishes a foundation for drug development and new types of medical treatment strategies.

In 1972 Stanley Prusiner began his work after one of his patients died of dementia resulting from Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). It had previously been shown that CJD, kuru, and scrapie, a similar disease affecting sheep, could be transmitted through extracts of diseased brains. There were many theories regarding the nature of the infectious agent, including one that postulated that the infectious agent lacked nucleic acid, a sensational hypothesis since at the time all known infectious agents contained the hereditary material DNA or RNA. Prusiner took up the challenge to precisely identify the infectious agent and ten years later in 1982 he and his colleagues successfully produced a preparation derived from diseased hamster brains that contained a single infectious agent. All experimental evidence indicated that the infectious agent was comprised of a single protein, and Prusiner named this protein a prion, an acronym derived from “proteinaceous infectious particle.” It should be noted that the scientific community greeted this discovery with great skepticism, however, an unwavering Prusiner continued the arduous task to define the precise nature of this novel infectious agent.

The infectious prion particle forms within the body

Where was the gene encoding the prion, the piece of DNA that determined the sequence of the amino acids comprising the prion protein? Perhaps the gene was closely associated with the protein itself as in a small virus? The answers to these questions came in 1984 when Prusiner and colleagues isolated a gene probe and subsequently showed that the prion gene was found in all animals tested, including man. This startling finding raised even more questions. Could prions really be the causative agent of several dementia-type brain diseases when the gene was endogenous to all mammals? Prusiner must have made a mistake! The solution to this problem became evident with the sensational discovery that the prion protein, designated PrP, could fold into two distinct conformations, one that resulted in disease (scrapie PrP = PrPSc) and the other normal (PrP = PrPc). It was subsequently shown that the disease-causing prion protein had infectious properties and could initiate a chain reaction so that normal PrPc protein is converted into the more stabile PrPSc form. The PrPSc prion protein is extremely stabile and is resistant to proteolysis, organic solvents and high temperatures (even greater than 100o C). With time, non-symptomatic incubation periods vary from months to years, the disease-causing PrPSc can accumulate to levels that result in brain tissue damage. In analogy to a well known literary work, the normal PrPc can be compared to the friendly Dr. Jekyll and the disease causing PrPSc to the dangerous Mr. Hyde, the same entity but in two different manifestations.

Mutations in the prion gene cause hereditary brain diseases

The long incubation time for prion based disease hampered the initial efforts to purify the prion protein. In order to assess purification schemes Prusiner was forced to use scores of mice and in each experiment wait patiently for approximately 200 days for the appearance of disease symptoms. The purification efforts accelerated when it was demonstrated that scrapie could be transferred to hamsters, animals that exhibited markedly shortened incubation times. Together with other scientists, Prusiner cloned the prion gene and demonstrated that the normal prion protein was an ordinary component of white blood cells (lymphocytes) and was found in many other tissues as well. Normal prion proteins are particularly abundant on the surface of nerve cells in the brain. Prusiner found that the hereditary forms of prion diseases, CJD and GSS (see the last section), were due to mutations in the prion gene. Proof that these mutations caused disease was obtained when the mutant genes were introduced into the germline of mice. These transgenic mice came down with a scrapie-like disease. In 1992 prion researchers obtained conclusive evidence for the role of the prion protein in the pathogenesis of brain disease when they managed to abolish the gene encoding the prion protein in mice, creating so called prion knock-out mice. These prion knock-out mice were found to be completely resistant to infection when exposed to disease-causing prion protein preparations. Importantly, when the prion gene was reintroduced into these knock-out mice, they once again became susceptible to infection. Strangely enough, mice lacking the prion gene are apparently healthy, suggesting that the normal prion protein is not an essential protein in mice, its role in the nervous system remains a mystery.

Structural variant disease-causing prions accumulate in different regions of the brain

Specific mutations within the prion gene give rise to structurally variant disease-causing prion proteins. These structural prion variants accumulate in different regions of the brain. Dependent upon the region of the brain that becomes infected, different symptoms, typical for the particular type of disease are evident. When the cerebellum is infected the ability to coordinate body movements declines. Memory and mental acuity are affected if the cerebral cortex is infected. Thalamus specific prions disturb sleep leading to insomnia, and prions infecting the brain stem primarily affect body movement.

Other dementias may have a similar background

Prusiner’s pioneering work has opened new avenues for understanding the pathogenesis of more common dementia-type illnesses. For example, there are indications that Alzheimer’s disease is caused when certain, non-prion, proteins undergo a conformational change that leads to the formation of harmful deposits or plaques in the brain. Prusiner’s work has also established a theoretical basis for the treatment of prion diseases. It may be possible to develop pharmacological agents that prevent the conversion of harmless normal prion proteins to the disease-causing prion conformation.

Intrinsic defense mechanisms do not exist against prions

Prions are much smaller than viruses. The immune response does not react to prions since they are present as natural proteins from birth. They are not poisonous, but rather become deleterious only by converting into a structure that enables disease causing prion proteins to interact with one another forming thread-like structures and aggregates that ultimately destroy nerve cells. The mechanistic basis underlying prion protein aggregation and their cummulative destructive mechanism is still not well understood. In contrast to other infectious agents, prion particles are proteins and lack nucleic acid. The ability to transmit a prion infection from one species to another varies considerably and is dependent upon what is known as a species barrier. This barrier reflects how structurally related the prions of different species are.

Prion diseases in animals and man

Without exception, all known prion diseases lead to the death of those affected. There are, however, great variations in pre-symptomatic incubation times and how aggressively the disease progresses.

Scrapie, a prion disease of sheep, was first documented in Iceland during the 18th century. Scrapie was transferred to Scotland in the 1940s. Similar prion diseases are known to affect other animals, e.g., mink, cats, deer and moose.

Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) – Mad cow disease is a prion disease that has recently received a great deal of publicity. In England BSE was transmitted to cows through feedstuff supplemented with offals from scrapie-infected sheep. The BSE epidemic first became evident in 1985. Due to the long incubation time the epidemic did not peak until 1992. In this year alone roughly 37,000 animals were affected.

Kuru among the Fore-people in New Guinea was studied by Carleton Gajdusek (recipient of the 1976 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine). Kuru was shown to be transmitted in connection with certain cannibalistic rituals and was thought to be due to an unidentified “slow virus”. The infectious agent has now been identified as a prion. Duration of illness from first symptoms to death: 3 to 12 months.

Gertsmann-Sträussler-Scheinker (GSS) disease is a hereditary dementia resulting from a mutation in the gene encoding the human prion protein. Approximately 50 families with GSS mutations have been identified. Duration of illness from evidence of first symptoms to death: 2 to 6 years.

Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI) is due to another mutation in the gene encoding the human prion protein. Nine families have been found that carry the FFI mutation. Duration of illness from evidence of first symptoms to death: roughly one year.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) affects about one in a million people. In 85-90% of the cases it has been shown that CJD occurs spontaneously. Ten to fifteen per cent of the CJD cases are caused by mutations in the prion protein gene. In rare instances CJD is the consequence of infection. Previously infections were transmitted through growth hormone preparations prepared from the pituitary gland of infected individuals, or brain membrane transplants. About 100 families are known carriers of CJD mutations. Duration of illness from evidence of first symptoms to death: roughly one year.

A new variant of CJD that may have arisen through BSE-transmission. Since 1995 about 20 patients have been identified that exhibit CJD-like symptoms. Psychological symptoms with depression have dominated, but involuntary muscle contractions and difficulties to walk are also common.

|

| The figure schematically illustrates how variants of disease causing prions affect different parts of the brain. In Bovine Spongiform Encephalitis (BSE), the brain stem is affected, in Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI), the thalamus region, in Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD), the cerebral cortex, while in KURU and Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker (GSS) disease the cerebellum is damaged. |