Transcript from an interview with Thomas C. Südhof

Interview with Thomas C. Südhof, 6 December 2013, during the Nobel Week in Stockholm, Sweden.

Could you explain your Nobel Prize awarded work to young students?

Thomas Südhof: To actually explain that one has to sort of introduce the subject in little broader terms. A person, I think most people would agree, is a person because of in the end of a person’s brain, which is where people think, plan and where all perceptions are collected and processed. I am a neuroscientist, I work on how the brain works which is an unbelievable big challenge because it’s a really quite amazing organ. In principle how the brain works is easy enough to explain. Billions and billions of nerve cells that constantly talk to each other and by talking to each other process information and at some point, come to some decision of doing something. What we have been doing over decades now, ever since I started in science, trying to understand how nerve cells in the brain communicate with each other so our contribution to science in a broad sense was to shed light on how a nerve cell speaks to another nerve cell and the way a nerve cell does that is via the specialized connection that is formed between these cells and the brain and that connection is called a synapse. And a synapse transfers information and processes information from one nerve cell to the next. It is a specialized junction between nerve cells that is not only there to relay information but also to change information, its own little nano computer. if you want to call it that. What we have done is to try to understand better how one cell sends out the information to the next cell at the synapse and ideally how also it processes that information and our major contributions I believe was in figuring out the basic fundamental molecular processes that govern this ability of a nerve cell in all brains, in all cells and in all animals.

So basically, the communication is in the brain?

Thomas Südhof: Fundamentally our work deals with trying to understand how brain cells communicate, yes. How exactly, what is the molecular basis, what are the genes, how do they work? What is the atomic structure? How are they regulated? How does their activity effect the overall brain? And how does that change in disease?

What were you doing when you got the message of being awarded the Nobel Prize?

Thomas Südhof: The question of what I was doing when I got the Nobel Prize call, a question that has been asked a thousand times. I think many people have listen to the call that was recorded and which I didn’t know and put on the website and I was driving in the middle of Spain trying to find a small city where I was supposed to go for a conference. Most people who live in the United States, if they have the fortune or luck or both to get such a call, most people are sleeping except if they expect it, and the usual procedure is as I understand, that you first get the call and then you are called and the recording is only done for the time you are called again, so most people are prepared. They know what they are going to do and my co-laureates already had showered when they got the call, so the situation was a little different for me because the first call never reached me. Adam Smith, who is part of Nobel Media I understand, was actually the one who called me and my first thought was quite honestly skeptic, skepticism, I was skeptic about the call, I felt that there was something not quite … It didn’t sound right that somebody with high-English accent would call you about that, so I was a little cautious, I was also a little sleepy because I hadn’t slept the night before of course, I was flying. I had to gather my wits and try to figure out whether that was actually a truthful call or a prank call.

At what point did you realize your work was a breakthrough?

Thomas Südhof: The question of sort of a major discovery point or single event is often asked. Most Nobel Prizes are given, I believe, for technical advances or because such moments are identifiable in the discovery of techniques, monoclonal antibodies, patch clamping and so on. Much fewer Nobel Prizes are actually given for discoveries of how something works, which is because, in my personal view, most discoveries of how something works are not discoveries that can be incapsulated in a single moment. The discoveries that require an incremental advance over many different experiments. If you want to understand the process, you can’t understand it in a single experiment. You have to approach it from many different angles. In my personal case the work that we performed that I think led to this prize was actually work that initiated 25 years ago and there were a lot of important observations, but in the end the promise of these observations only materialized or became more concrete very recently because continuing experiments in our lab backed them up, expanded them, explained them and gave them substance. I actually don’t think that there was any single eureka moment in my career, there were many small eureka moments, but not just one discovery, it’s in fact the whole question I am working on and I think that our work has contributed to understanding a process that involves or necessitates, more than understanding one little thing or one big thing, but understanding really how it works.

Who is your role model, and why?

Thomas Südhof: There is many people who have inspired me during my career. When I grew up I was probably most inspired by some of the teachers who I most admired, like music teachers for example, not science teachers I am afraid. I greatly admire and was tremendously influenced as a role model if you like by my mentors Joe Goldstein and Mike Brown who were my mentors in my post-doctoral training and who are Nobel Laureates. I think I have always admired people who have had the ability yo actually make discoveries that allow us to understand something and not only to discover a new approach and a new technique and I see this with Brown and Goldstein. I can also see that for example in the work that Bert Sakmann did after he won the Nobel Prize, which he won as you probably know for patch clamping, but afterwards he became a true, well actually he developed neuroscience in a way that I found very inspiring and so those are people I could mention here.

Is there anything else you would like to share with us?

Thomas Südhof: The one thing that I always feel I would like to always express is that what I appreciated about the Nobel Prize in particular and what I think is absolutely essential for science, not only science, but for our societies and maybe even for civilization in a broad sense is that science operates purely or should operate purely by the idea of figuring out what the truth is about real things, but it is done by humans and humans are by their very nature never always truthful. I really appreciate about the Nobel Prize that historically it is has always been unbelievably well done, in the sense that the selection was … I can’t say this about my own case, but about previous cases were really based on scholarship and I think that is an enormous achievement. I think that that’s really what constitutes the value of the prize and I can only really congratulate the Nobel, I don’t know actually who does this, but I can only congratulate them on doing such a wonderful job.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Transcript from an interview with Randy W. Schekman

Interview with Randy W. Schekman on 6 December 2013, during the Nobel Week in Stockholm, Sweden.

Could you explain your Nobel Prize awarded work to young students?

Randy Schekman: My work involves studying how protein molecules, which are the machines that operate life, how some of them are shipped outside of a cell, Almost all the cells in our body produce most of the proteins that act inside the cell and do the chemistry of life, but about 10% of the proteins on average are special proteins that have to be incapsulated and then sent by export out of the cell and these are proteins that everyone knows about, insulin, growth factors , hormones, all of the proteins in your blood are actually manufactured inside of a cell and then have a special machinery for their export. This pathway was first understood by using the electron microscope to peer inside of a human pancreatic cell and the Nobel Prize in 1974 was given to a pioneer by name of George Palade who understood how the machinery inside of the cells conveyed molecules outside of the cell. What he didn’t understand, because of the technics available at the time, was how these machines operate.

When I started my career at Berkeley I chose to study baker’s yeast which is not a traditional system to evaluate protein secretion but they still, that’s how they grow and divide, they actually secret and assemble their membrane using this process and secretion. My first graduate student, one of my first students, Peter Novick and I developed a genetic approach that allowed us to isolate mutations that cripple this process and when we did so we were able to see that these cells use a process that’s essentially the same as human cells and as a result the biotechnology industry was able using yeast as a vehicle for the production of useful human proteins in fact. One third of the world supply of human insulin is made secretion and yeast so we what we did which was just very basic turned out to have quite practical application.

What brought you to science?

Randy Schekman: My dad was an engineer so there was some interest in science. My own interest developed when I was very young. I had a toy microscope and I was fascinated with life forms that I could see in pond scum. I saved up my money and I brought a professional microscope when I was a young teenager and I have actually just today donated that microscope to the Nobel Museum. It’s really very important in my early development of an interest in microbiology and that just sort of naturally evolved and when I got to university I continued to study viruses and microorganisms and that interest has continued to this day.

How did you learn that you had been awarded the Nobel Prize?

Randy Schekman: At 01.20 in the morning on October 7 I was fast asleep. The phone rang, I am not sure I heard it, my wife yelled out: “This is it!” so I stumbled out of bed, still half asleep, got to the phone and I think I was trembling at this point, but I am pretty sure I knew what it was, and I was greeted by a nice Swedish accent on the other side, Göran Hansson. At that point I think I said: “Oh my god” and then he assured me after congratulating me that it was not a hoax and then the fog lifted so I sort of decided how I had to proceed for the next hour or so before the press conference. The first person I called was my father, 86 years old, who has been hopeful for years about this, so he was ecstatic. I called my kids, I called my best friend and then I called the press officer at Berkeley because I was warned years ago that I had do this and as result there were two press officers in my home at 02.30 in the morning lining up the TV-camera crews and since then my life has not been the same.

Who is your role model, and why?

Randy Schekman: I had many people who were inspiring models, two of them stand out though, one was my graduate adviser Arthur Kornberg who had the very highest standards in science and scholarship of anyone that I had ever met, really rigorous, very demanding, tough guy, but I learnt I great deal from him how to do science. And at a very different level, another great scientist, Daniel Koshland was the chairman of the biochemistry department at Berkeley when I was hired as a beginning faculty member. He had in additional to great scientific qualities a concern for science as a leader of scientists. He was chairman of the department, he was very collegial, concerned about promoting the university and promoting public higher education and I have taken his example in doing the many other things that I do. I value him as highly as I value what I learnt from Kornberg. He was the editor of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, then he became the editor of Science magazine and I followed in his footsteps. I was for five years the editor in chief of the Proceedings of the National Academy, but then more recently I have taken on a new role as an editor of a new online journal called e-Life which is journal sponsored by Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Wellcome Trust and Max Planck Society. We feel very strongly that there’s a need for another journal at the very high end where the decisions are made by active scientists and where the limitations impose by the print model do not apply so we accept papers and publish full length papers and we don’t have artificial restrictions based on some feather fashion so this is a journal that I am promoting. Actually, from here in Stockholm I will be speaking to journalists about his.

Have you ever had an eureka moment?

Randy Schekman: There is a eureka moment that happened early on in the work that Novick and I were doing. He isolated the first mutant and he could see, using simple assays, that the enzymes that normally are secreted outside of the yeast cell in this mutant now build up inside the cell. But the most dramatic moment came when he looked, using the electron microscope, at sections of this cell. He called excitedly up to my office from down in the basement where the electron microscope was and I went down and I had a look. It was revelation to see a cell that ordinarily has only a sort of sparse collection of organelles but which instead in this mutant had, it was just dying of overload of the vesicles that were being produced, but couldn’t be delivered to the cell surface and so the cell has just accumulated lots of vesicles. That image stands in my mind as really the beginning of my career and I knew from that moment that I would be consumed for at least the next 20 years trying to figure it all out, so that was really a lucky break.

Do you know how you are going to spend your Nobel Prize money?

Randy Schekman: Unfortunately in my lifetime the funding of public higher education has gone down dramatically so for instance when I was a university student at UCLA I could work a summer job and pay fees and room and board and books for the rest of the year. My father had five kids and they all went to public institutions; he never had to pay anything. Now in US students have to assume the responsibility for their higher education themselves. They go into tremendous debt, there’s a trillion-dollar debt just owed to educational institutions in the US that just didn’t exist when I was growing up. I think this is a wholesale change in the political atmosphere that is I think really damaging, so I feel very strongly about this and as the result, the one action that I could do is that I donated my Nobel Prize money for the creation of an endowed chair at my institution so we can be as competitive as the private institutions and brining the best young scholars to Berkeley.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Transcript from an interview with James E. Rothman

Interview with James E. Rothman on 6 December 2013, during the Nobel Week in Stockholm, Sweden.

Could you explain your Nobel Prize awarded work to young students?

James E. Rothman: To the young teenagers and other students when you study science and you start thinking about the human body. One of first things that you are taught is that the body has a lot of parts, we have our brain, we have our muscles and we have the various parts inside the body, the so-called organs. They teach you a lot about these different parts of the body, but one of the most important things is how the different parts of the body talk to each other. How does the brain talk to the muscle to tell you to move an arm, for example? We call that synaptic or neuronal communication. How does your stomach talk to your pancreas to cause hormones like insulin to control the sugar that you are eating and make sure that the right amount of sugar goes throughout your body and then to your brain so your brain can be thinking in a way because I hope you are right now if you are listening to this. It is those very basic questions of cell to cell communication in the body that professors Südhof, Schekman and I have helped to understand.

What brought you to science?

James E. Rothman: You know there are some scientists who … they sort of get into science accidently, they met somebody, or they saw somebody or whatever their story is. In my case I can’t ever remember not wanting to be a scientist. I think I briefly flirted with the idea of driving a locomotive train when I was probably two or three. I was very fortunate to come from a family that was very focused on education. My father was a doctor in a small town, but education and especially science and medicine were an important part of the sort of family culture and so I also grew up in the United States of America. I was born in 1950, the significance in that was that after world war two America was really at that time seen it was becoming and it already was a very powerful country. It was taking on global responsibilities including scientific research, but also in a major competition with the Soviet Union as everybody knows, the so-called Cold War. When the Soviets developed the nuclear bomb and when they also were the first to put satellites into space, quite frankly it scared the wham out of certainly Americans, but certainly a lot of the world. It caused an energy … the whole enterprise of scientific research especially the physical sciences, but also biomedical sciences got energized. So that’s the environment that I grew up in and in that environment scientists and medical doctors doing research and so on, we are really prized by society. I am not entirely sure that’s so true today, but it was certainly true then and we were seen as assets, very little in the liability call, so you know as a young boy your hero might have been a baseball player, but it might also have been a physicist like Oppenheim or Einstein.

Who is your role model, and why?

James E. Rothman: Sometimes I get asked the question, who is my role model? I guess the answer to that is it probably depends at what age. When I was really young and probably did have role models that affected me, I didn’t know the concept of a role model. I actually think that the role models that we have that really help determine our character. I mean of course there are our parents and our friends, made a family, but I don’t think we really think about that at the time when it has the most effect. Later on in life, as you are an adult, you have your teachers and I have had mine, but I guess I feel like I have had many, not just one and I have been very fortunate for that reason. I think people who are successful in life have the wonderful accident of having had, whether intentional or not, sometimes you find the person who you admire, that’s a skill, but the ability to have that skill to seek out a role model is something that probably is acquired through role models that we don’t seek out.

As a young scientist there was a great biochemist who was very influential to me and also, I have to say when you interview Randy Schekman I am sure you hear the same name. His name was Arthur Kornberg. Arthur Kornberg was one of the great biochemists of the twentieth century, possibly the greatest biochemist of the second half of the twentieth century. He was my hero as I was learning biochemistry and I actually left medical school without finishing my medical doctor’s degree in order to take the opportunity to work in a laboratory next to professor Kornberg. My first job as an independent scientist was as a young professor at Stanford University and Arthur was the chief of the department really and actually was a great inspiration to me. The work that was recognized in this Nobel Prize, my contribution to it, began during that period and I don’t think that I would have been as successful in doing what I did if it were not for the kind of scientific environment that he fostered and the type of science that he represented which we called enzymology. He was without a doubt the master of enzymology of his era and for me to have the opportunity to take that discipline to a new level under the watchful eyes of the master was quite an extraordinary experience. He won the Nobel Prize by the way many years ago and I believe 1959.

At what point did you realize your work was a breakthrough?

James E. Rothman: It’s always difficult to know at any one time as a basic scientist whether what you are doing at that time is going to have some monumental significance. I am not sure my work has monumental significance, but it certainly has been recognized as having some significance. The thing about basic science is that we any one day, any one experiment, you never really know, you try your best every single day. I tell my students every day that you work in the lab is a day that you will never have again, so think very carefully to do the most important thing that you can do every day. But the nature of science is such that if you are doing real research on the frontier where nobody has ever been, it doesn’t always work. The hardest thing about being a scientist is you have to be prepared to fail most of the time. A Nobel Laureate might be a scientist who fails only 99% of the time, maybe everybody else is a little bit less luckier or whatever fails 99.9% of the time. By definition what you are doing at any one time, it’s a little hard to know if it’s the most important. On the other hand, when it does happen, and it’s happened to me actually twice. I have had very special moments and I kind of understood and everybody around me kind of understood that it was a special moment. We celebrated some of the basic discoveries at the time they were made with my co-workers. With scientists, it’s also very important for students especially, to understand that science these days is not a solo enterprise, it’s the work of a team. It’s students, professors and we all contribute, not everyone gets recognized with the Nobel Prize, but there are a lot of people who contribute.

What were you doing when you got the message of being awarded the Nobel Prize?

James E. Rothman: The experience of getting a telephone call from Stockholm at 04.30 in the morning is absolutely singular. I was of course sleeping when it came, but not for long and woke up rather abruptly. I went to sleep actually quite late the night before and perhaps had a little too much to drink and but my wife Joy of course woke up at the same time and said: “This might be it!” and of course I was thinking the same thing and sure enough it was and there was a voice not entirely unfamiliar to me, professor Hansson, I had met on a couple of meetings, didn’t know him well, but it was wonderful news.

Is basic research important?

James E. Rothman: It’s a terrific honor to be recognized by a Nobel Prize. This year we have three Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine and the emphasis, as the Nobel Committee mentioned in their announcement, is on the physiology, but also the medicine. This is a basic science prize and it recognizes fundamental research whose medical implications are not immediate, they will happen, some of them are already happening, but what it really does is it celebrates the importance of understanding the life process in and of itself. That focus on the importance of fundamental research, in this case in the life sciences, is something that the Nobel Prize contributes importantly to, because oftentimes this type of work goes less noticed than the next momentary medical advance or clinical trial and funding for basic science research around the world is in serious jeopardy, particularly in the United States, but not only in the United States and certain parts of Europe, even here in Sweden. Although there is good funding for basic research, it could be better and so it’s really important that the type of work that we represent and what we represent is just a tip of an iceberg and there are many of tips and it’s great when these tips of the iceberg are recognized from time to time.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Randy W. Schekman – Facts

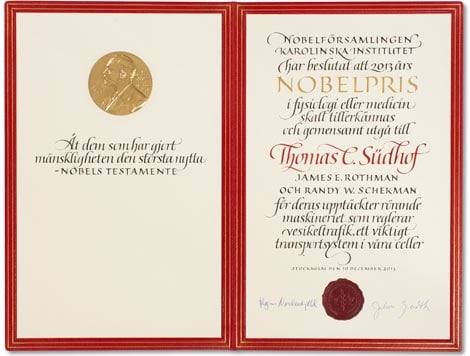

Thomas C. Südhof – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2013

Calligrapher: Susan Duvnäs

Book binder: Ingemar Dackéus

Photo reproduction: Lovisa Engblom

Randy W. Schekman – Other resources

Links to other sites

Randy Schekman’s Nobel Morning

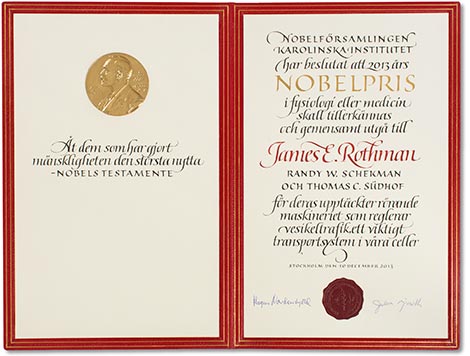

James E. Rothman – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2013

Calligrapher: Susan Duvnäs

Book binder: Ingemar Dackéus

Photo reproduction: Lovisa Engblom

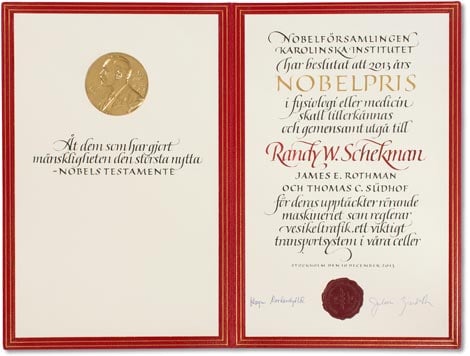

Randy W. Schekman – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2013

Calligrapher: Susan Duvnäs

Book binder: Ingemar Dackéus

Photo reproduction: Lovisa Engblom

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2013

Thomas C. Südhof – Biographical

Upbringing

I was born in Göttingen on December 22, 1955. At that time, the aftermaths of the Second World War were still reverberating. Mine was an anthroposophical family; my maternal grandparents had been early followers of Rudolf Steiner’s teaching, and worked for Waldorf schools when Hitler assumed power and banned the anthrophosophical movement. Waldorf schools were forced to close, and my grandfather was conscripted to work in a chemical munitions factory – it was a miracle he survived the war. My uncle was drafted into the army out of school, and when I was born, he had just returned from the Soviet Union after 10 years as a prisoner of war. I was the second of four children. My parents were physicians, with my father pursuing a career in academic medicine, while my mother cared for our growing family. My father’s training led him to the United States during the time I was born; as a result, he learned of my arrival by telegram as he was learning biochemical methods in San Francisco, close to where – by a twist of fate – I now live.

I spent my childhood in Göttingen and Hannover, and graduated from the Hannover Waldorf School – resurrected after the war – in 1975. My strongest childhood memories were those of my maternal grandmother telling me stories about the time during the war, how she was reading Dostoyevski while trying to escape the bombs in underground shelters and hoping that my grandfather would survive. She imbued me with the importance of Goethe and detested Kant, whom I learned to love. I learned from my grandmother how important an intellectual life is under any circumstance, and that values are spiritual even if you are an atheist.

My father was a successful doctor who managed an entire hospital district and wrote countless books on general internal medicine; he worked very hard, and was continuously frustrated by what he felt were the inadequacies of the medical care system and the academic world. However, when I was in high school, my father died of a heart attack, brought about by inattention to his health, and my mother had to cope with life alone with four children – a difficult and sad but an also partially liberating experience for her, as she explained to me later. Her strength was an example to me, her ability to accept what happened without giving up, and to concentrate on what was important to her.

I had been interested in many different subjects in high school, in fact all subjects except for sports which I found primitive – now ironic to me as I have become addicted to regular exercise. Early on, I became fascinated by classical music. After unsuccessful attempts at playing the violin, I gave this instrument up to the delight of everyone around me who had to listen to me trying. However, I then decided to learn to play bassoon, which I pursued with a vengeance, motivated by a wonderful teacher (Herbert Tauscher) who was the solo-bassoonist at the local opera house, and who probably taught me more about life than most of my other teachers. I credit my musical education with my dual appreciation for discipline and hard work on the one hand, and for creativity on the other. I think trying to be marginally successful in learning how to be a musician taught me how to be a scientist: there is no creativity if one does not master the subject and pay exquisite attention to the details, but there is also no creativity if one cannot transcend the details and the common interpretation of such details, and use one’s mastery of the subject like an instrument to develop new ideas.

I did not know what to do with my life after school, except that I was determined not to serve in the military. More by default than by vocation, I decided to enter medical school, which kept all avenues open for a possible career in science or as a practitioner of something useful – as a physician – and allowed me to defer my military service. I thought that music, philosophy, or history were more interesting subjects than medicine, but I did not feel confident that I had sufficient talent to succeed in these difficult areas, whereas I thought that almost anybody can become a reasonably good medical doctor.

First Experiments

I studied first in Aachen, the beautiful former capital of Charles the Great, and then transferred to Göttingen, the former scientific center of the Weimar republic, in order to have better access to laboratory training since I became more and more interested in science.

Soon after arriving in Göttingen, I decided to join the Dept. of Neurochemistry of Prof. Victor P. Whittaker at the Max-Planck-Institut für biophysikalische Chemie as a ‘Hilfswissenschaftler’ (literally an ‘assisting scientist’, but more accurately a kind of ‘sub-scientist’). I was attracted to Whittaker’s department because it focused on biochemical approaches to probe the function of the brain, following up on Whittaker’s development of purification methods for synaptosomes and synaptic vesicles in the two preceding decades. Moreover, when I entered his lab, Whittaker had become increasingly interested in the cell biology of synaptic vesicle exo- and endocytosis, which I thought were fascinating. However, I never got a chance to work on the brain or synaptic vesicles when I was in Whittaker’s lab. As a lowly ‘Hilfswissenschaftler’, I was assigned to the task of examining the biophysical structure of chromaffin granules, which are the secretory vesicles of the adrenal medulla that store catecholamines. Although my project developed well, I started exploring other questions in parallel as I became more and more familiar with doing experiments, while simultaneously studying medicine at the university. A helpful factor was that my supposed supervisor, a senior US scientist who worked with Whittaker, departed soon after I started in Whittaker’s lab, leaving me completely alone in my experiments since Whittaker was not really interested in that work. I am infinitely grateful to Victor Whittaker for giving me complete freedom in his department in pursuing whatever I thought was interesting. I continued working in his department after my graduation from medical school in 1982 until I moved to the US a year later in 1983.

Among the work I performed during my time in Whittaker’s department in Göttingen, the most significant is probably the isolation and characterization of a new family of calcium-binding proteins that we called ‘calelectrins’ because we had initially purified them from the electric organ of Torpedo marmorata, although we also identified them in bovine liver and brain. ‘Calelectrins’ were among the first identified members of an enigmatic and evolutionarily ancient family of calcium-binding proteins now called annexins. Annexins were at the same time discovered in several other laboratories, and I am proud of the fact that we contributed to the first description of this intriguing protein family, although to this date their function remains unknown.

Postdoctoral Training

After finishing medical school, I decided to become an academic physician, along the mold of my deceased father. Although my time in Whittaker’s laboratory had taught me to love doing science, I wanted to do something more practical, exciting, and immediately useful than what I had seen in the Max-Planck-Institut in Göttingen. The standard career for an academic physician in Germany was to go abroad for a couple of years to acquire more clinically oriented scientific training before starting her/his clinical specialty training. Upon surveying the scientific landscape, I decided to join the laboratory of Mike Brown and Joe Goldstein at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas for postdoctoral training. Brown and Goldstein were already famous for their brilliant cell-biological studies when I made this decision. They were equally renowned for using cutting-edge scientific tools to address a central question in medicine, namely how cholesterol in blood is regulated. When I announced my decision to go to Dallas instead of the more conventional Boston or San Francisco, my friends and family were disappointed, but it was the best professional decision I ever made.

While in Joe Goldstein’s and Mike Brown’s laboratory, I cloned the gene encoding the LDL receptor, which taught me molecular biology, revealed to me the beauty of sequences and protein organizations, and opened up genetic analyses of this gene in human patients suffering from atherosclerosis. I also became interested in how expression of the LDL receptor is regulated by cholesterol, and identified a sequence element in the LDL receptor gene called ‘SRE’ for sterol-regulatory element that mediates the regulation of the LDL receptor expression by cholesterol. During my time in their laboratory, Joe Goldstein and Mike Brown were awarded the Nobel Prize (in 1985), which I still consider one of the best Nobel Prizes given. After I left, discovery of the SRE led to the identification of the SRE-binding protein in Brown and Goldstein’s laboratory, which in turn identified new mechanisms of transcriptional regulation effected by intramembrane proteolysis.

The contrast between Göttingen and Dallas could not have been bigger. When I arrived in Dallas, Texas was not yet the extremely conservative bastion of religious fundamentalism that it is now, but a vast state with an optimistic ‘can-do’ culture that was very different from the culture to which I had been exposed in Göttingen. The difference in scientific environment was even more extreme. In Dallas, scientific life was teeming with enthusiasm and energy, work was a pleasure, and excitement was pulsating through every experiment because the importance of the goals was self-evident. In Göttingen, as I realized when I was in Dallas, although the approach was very scholarly in the sense of pursuing knowledge, much of that pursuit was without regard to the importance of the subject. As a result, people often asked uninteresting questions, and possibly even wasted their time. To this date, I find it one of the hardest challenges in science to achieve the right balance between trusting my own judgment and listening to others. If I only rely on my own judgment, there is no corrective for mistakes, no adjustment of unreasonable impressions. However, if I listen only to the ‘world’, I will only follow fashions, will always be behind, and often will be just as wrong. Among the many things I credit Brown and Goldstein with for teaching me, the realization of this challenge and their example of how to deal with this challenge is among the most important. This challenge resembles that of composing music in which pure harmony is boring and meaningless, but pure dissonance is unbearable, and it is really the back and forth between these extremes that creates meaning.

Early Years of the Südhof Lab

In 1986, at the end of my postdoctoral training, I faced the choice of resuming my clinical training, or of establishing my own laboratory. Probably the best advice Brown and Goldstein gave me was now: they suggested I forego further clinical training and do ‘only’ science, and they backed up this advice by providing me with the opportunity to start my own laboratory at Dallas. This I did, and ended up staying for another 22 years, interrupted only by a short guest appearance as a Max-Planck Director in Göttingen (see below).

When I started my laboratory at Dallas in 1986, I decided to attack a question that was raised by Whittaker’s work, but neglected since: what are synaptic vesicles composed of, and how do they undergo exo- and endocytosis, i.e., what is the mechanism of neurotransmitter release that underlies all synaptic transmission? We had learned from Whittaker’s work that synaptic vesicles could be biochemically purified, but nothing was known about the molecular mechanisms guiding synaptic vesicle exo- and endocytosis. Our initial approach, performed in close collaboration with Reinhard Jahn, whose laboratory at that time had just been set up in Munich, was simple: We set out to purify and clone every protein that might conceivably be involved, and worry about their functions later. This approach was initially criticized for being too descriptive, but turned out to be more fruitful than I could have hoped for, and has arguably led to a plausible understanding of neurotransmitter release.

In the nearly three decades since I started my laboratory, our work, together with that of others, led to the identification of the key proteins that are involved in synaptic vesicle exocytosis. In particular, this work shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying membrane fusion during synaptic vesicle exocytosis, explained how calcium signals control these mechanisms, and described the molecular organization of the presynaptic terminal that allows fast coupling of an action potential and the ensuing calcium influx to neurotransmitter release. Some of the proteins whose function we identified are now scientific household names and have general roles in eukaryotic membrane fusion that go beyond a synaptic function, while other proteins are specific to synapses and in part account for the exquisite precision and plasticity of synapses as elementary computational elements in brain. I feel fortunate to have stumbled onto this overarching neuroscience question at a time when it was ready to be addressed, and it has been tremendous fun to work our way through the various synaptic proteins and their properties that shape the functions of these proteins.

It is important to note, however, that the nature of our studies was not revolutionary. In my career, no single major discovery changed the field all at once. Instead, our work progressed in incremental steps over two decades. I think this is a general property of scientific progress in understanding how something works – a single experiment rarely explains a major question, but usually a body of work is required. In contrast, scientific progress in developing tools normally advances in spurts, and often a single flash of genius creates a completely new method (e.g., see monoclonal antibodies, patch clamping, PCR, or shRNAs, to name a few).

The closest our work came to inducing a radical change in the field was probably the identification of synaptotagmins as calcium-sensors for fusion, and of Sec1/Munc18-like proteins (SM-proteins) as membrane fusion proteins, but both hypotheses took decades to develop and to become accepted by the field – in fact, the SM-protein hypothesis was only recently adopted by others, 20 years after we proposed it, and is still in flux. Thus, our work in parallel with that of others (Reinhard Jahn, James Rothman, Jose Rizo, Randy Schekman, Richard Scheller, Cesare Montecucco, and Axel Brunger come to mind) produced a steady incremental advance that resulted a better understanding of how membranes fuse, one step at a time. As a result of this combined effort, we now know that SNAREs are the fusion catalysts at the synapse, first shown when SNAREs were shown to be the substrates of clostridial neurotoxins, that SM-proteins in general and Munc18-1 in particular are essential contributors to all membrane fusion events, that a synaptotagmin-based mechanism assisted by complexin underlies nearly all regulated exocytosis, and that synaptic exocytosis is organized in time and space by an active zone protein scaffold containing RIM and Munc13 proteins as central elements.

![The Südhof laboratory in Dallas in 1995. Sitting in the first row left to right: Thomas Rosahl, Martin Geppert, Ewa Borowicz, Izabella Kornblum [sitting behind the row], Else Fykse, Cai Li, Andrea Roth, Shirley Clement, Christopher Newton, and Greg Mignery. Standing left to right: Konstantin Ichtechenko, Alexander Petrenko, Thomas Südhof, Beate Ullrich, Andrei Khokhlatchev, Yutaka Hata, and Harvey McMahon.](https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/sudhof-bio-4-lab.jpg)

The work in my lab would have been impossible without the contributions of many brilliant postdoctoral fellows who have now gone on to successful careers on their own. Ever since I started my laboratory, I have found the pleasure of working with others the best part of my life. The continuing friendship of my former trainees has been one of the major satisfactions of my career. Among these were Mark Perin with whom I cloned synaptotagmin, Yutaka Hata who discovered Munc18, Martin Geppert who performed the initial mouse genetics experiments in my lab, Nils Brose who identified Munc13, Harvey McMahon who identified complexins, Yun Wang who isolated RIM, and many others who made essential contributions. Complementing these great co-workers, I had the best collaborators I could possibly wish for. Besides Reinhard Jahn (who had moved to Yale after Munich, and then on to Göttingen), the most important of these collaborators were Jose Rizo in Dallas with whom we worked out the atomic structures of many of the proteins we studied, Bob Hammer in Dallas who helped us with the mouse genetics, and Chuck Stevens at the Salk Institute who introduced us to the beauty of electrophysiological analyses.

My German Intermezzo

Ten years after I started my laboratory, while the work described above was progressing, I was offered the opportunity to return to Germany and to organize a Department of Neuroscience at the Max-Planck-Institut für experimentelle Medizin in Göttingen, my home town. I enthusiastically took on the challenge, planned and oversaw the building of a new animal facility, hired scientists, and organized the renovations and equipment of a suite of laboratories. However, after a few years the leadership of the Max-Planck-Society changed. It soon became clear that the Max-Planck-Society’s new president, Prof. Hubert Markl, developed doubts about my recruitment, and wanted to rebuild the institute that I was recruited into in directions that were quite different from what I had been promised. In a personal discussion, Prof. Markl suggested I resign my position at the Max-Planck-Institut and look for a future in the U.S., which I did.

I have never regretted my work for the Max-Planck-Institut in Göttingen, which laid the foundation for much of what happened there subsequently, including the subsequent recruitment of one of my postdoctoral fellows (Nils Brose) as a new director who has done a much better job than I could have done. However, I have also never regretted following Prof. Markl’s suggestion and returning to the U.S., where the breadth and tolerance of the system allowed me to operate in a manner that was more suitable for my somewhat iconoclastic temperament. Overall, my work as a director at the Max-Planck-Institut in Göttingen was a very positive experience that shaped my thinking when I subsequently had the opportunity to help build the Department of Neuroscience at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Maturity

Soon after I returned full-time to UT Southwestern at Dallas in 1998, I accepted the position of director of the Center for Basic Neuroscience, which was later transformed into the Department of Neuroscience. Building a Center and Department of Neuroscience partly occupied the following ten years, and was a lot of fun. Southwestern had a free-flowing and unbureaucratic environment that was extremely supportive. It was a pleasure to hire young people and see them develop, and I greatly appreciated the support of my colleagues in every respect.

Scientifically the 10 years between 1998 and 2008 were even more important. The flurry of discoveries of the 1990s created the impression that everything was already solved in membrane fusion and neurotransmitter release, but nothing could have been farther from the truth. I decided to continue to work on these questions, and believe that some of the most important observations in

the field came out of our work during that time period.

For example, it was well established in 2000 that SNAREs ‘do’ fusion and that they ‘do so’ by pulling membranes together, but it was unknown whether SNAREs were just nanomachines that acted as force-generators in approximating membranes, or whether they actually catalyze the fusion process, possibly by their transmembrane regions. Similarly, although we found that the SM-protein Munc18-1 was absolutely essential for fusion, Munc 18-1 appeared to bind to a form of the SNARE protein syntaxin-1 that was ‘closed’ and was thought to block fusion, whereas the yeast homolog Sec1p, as shown in elegant work by Peter Novick, bound to assembled SNARE complexes. How could the same protein be essential for fusion and inhibit SNARE-complex formation? Comparably puzzling questions surrounded the role of synaptotagmin as a calcium sensor in neurotransmitter release. Furthermore, a major question in understanding synapses had never been addressed, namely how the presynaptic machinery is organized in a manner that allows tight coupling of calcium-influx to the calcium-triggering of release. The significance of this latter question is often underestimated outside of the esoteric realm of neurophysiologists, but this tight coupling is the most important prerequisite for the speed and brevity of neurotransmitter release – in essence this coupling is what makes a synapse precise.

In the years after 1998, my lab and the labs of others, foremost those of my former postdoctoral fellows Nils Brose, Harvey McMahon, and Matthijs Verhage, of Christian Rosenmund, of Peter Novick, and of Jim Rothman, established several key points that address these questions. The most important was the demonstration that synaptotagmin is truly the calcium-sensor for release by showing that point mutations in synaptotagmin that change its calcium-affinity change release accordingly. Maybe equally important was the finding that Munc18 acts by binding to SNARE complexes after assembly, not by binding to one SNARE protein before assembly. Other significant findings of these years included the demonstration of the priming function of Munc13, the discovery that complexin acts as a ‘sidekick’ to support synaptotagmin function and that both synaptotagmin and complexin clamp minis in addition to the major action as activators of release, and that multiple synaptotagmins generally function as calcium-sensors in release. Moreover, in these years we identified specific chaperones that support the proper folding of SNAREs, opening up a new perspective on how SNARE function is maintained in neurons, an important issue because the loss of these chaperone activities were found to cause neurodegeneration. These were very productive years that did more than complete the stories we had begun in the 90s – they extended these stories into new directions, including an explanation of at least some forms of neurodegeneration. The one major issue that remained unresolved was how calcium-channels are recruited to the active zone, a question that was really only resolved after I moved to Stanford in 2008.

New and Old Directions

The currently final chapter in my career began when I moved my laboratory from UT Southwestern to Stanford University in 2008. After 10 years as a chair of a Neuroscience Center and then Department in Dallas, I felt that I wanted to devote more of my time to pure science, and to embark on a new professional direction, with an environment that was focused on academics. Moreover, I decided to redirect a large part of my efforts towards a major problem in neuroscience that appeared to be unexplored: how synapses are formed. Thus, in this currently last chapter of my work, I am probing the mechanisms that allow circuits to form in brain, and to form with often nearly magical properties dictated by the specific features of particular synapses at highly specific positions. I am fascinated by the complexity of this process, which far surpasses the numerical size of the genome, and interested in how disturbances in this process contribute to neuropsychiatric diseases such as autism and schizophrenia. This is what I would like to address in the next few years, hoping for at least some interesting insights.

As early as 1992, my laboratory had identified a family of cell-surface proteins called neurexins whose properties suggested that they may be involved in synapse formation. Neurexins were discovered because they are presynaptic receptors for the black widow spider venom component α-latrotoxin which paralyses small prey by causing excessive neurotransmitter release. However, the importance of neurexins and their ligands – such as the neuroligins, cerebellins, and neurexophilins which we and others identified – only became apparent in recent years when we started to analyze mouse mutants of these proteins.

Apart from these new directions, at Stanford we followed up on two ‘old’ questions about release: how calcium-channels are recruited to active zones, and what mediates the calcium-triggered release that remains in synapses which lack fast synaptotagmin calcium-sensor isoforms. Both questions had haunted me for decades – I was convinced of their importance but could not solve them. Only in the last few years did we develop answers to these questions in identifying the scaffolding proteins RIMs and RIM-BPs as the organizers of calcium-channels in the presynaptic active zone, and another synaptotagmin isoform (synaptotagmin-7) as a calcium-sensor for the remaining release in synaptotag-min-1 deficient forebrain neurons. Fittingly, this last observation was submitted a few weeks before the announcement of the Nobel Prize, and published coincidently with the award ceremony!

Life Lessons

After nearly 60 years of life and nearly 40 years as a scientist, I would like to draw the following personal conclusions, none of them very original. First, being a scientist, although socially a privilege and luxury, is not socially rewarding – for personal happiness, this profession is only worth it if a person obtains individual satisfaction in doing science. A scientist has to have the attitude of an adherent to Philip Spener’s pietism in Lutheran Germany in the 18th century – what counts are not outward successes, money, and social decorations, but the conviction of truth obtained from personal inspection of the evidence. After a glorious period of ascendance in Western Europe from Bacon’s England over Courvoisier’s France to Boltzmann’s Germany, the scientific method is now increasingly being challenged based on ideological grounds. In the most powerful country of the world, the United States, the majority of the governing elite at present feels free to dismiss some established scientific facts as fantasy, even suspecting evolution or climate science as communist conspiracies at a time when there is no communism left anywhere. At this stage – different from previous centuries – the only reason to pursue a career in science is an enormous curiosity to know what is really true.

Second, I at least have learned most from personal contacts, not from reading the literature or listening to talks. Although reading books or papers provided me with an indispensable background of facts, I learned how to think, how to assess a subject, and how to value a perspective from insightful comments of others. Thus, for a scientific career the most important elements are good teachers and mentors, and a great environment – not only during early years as student and postdoc, but throughout the entire career of a scientist. Now at an arguably rather advanced stage of my career, I need mentors and teachers more than ever – I need people who know better than I to tell me when I am wrong, and to make me aware of my mistakes! As an immediate consequence of this realization, I would advise everybody to make career choices primarily based on the people involved, not on the geographic location of a place or the fashionableness of the subject or the techniques. I believe this is true for all stages of a career.

Third, once a scientist has the opportunity to choose what to work on (increasingly a rarity in our world where political prescriptions of what scientists are supposed to discover are becoming more and more prevalent), he/she should make sure that whatever the choice of subject is, it is both important and tractable. I am personally often amazed about the choice of subject by some of my colleagues, possibly because I simply fail to recognize the importance of the subject. However, if one looks at the history of science over the last 50 years or so, I think one can argue that some approaches and goals have proved to be highly productive whereas others have not. For example, investments into bacterial and bacteriophage genetics early on eventually led to the golden age of molecular biology that all of science, but particularly cellular neuroscience, has benefitted from, whereas the parallel large investments into systems neuroscience has only recently started to bear some fruit after the tools developed by molecular and cellular neurobiology were beginning to be applied.

Finally, quantity doesn’t matter very much, nor does the place one publishes – in the end what counts is discovery which is often not immediately apparent. Most articles in “high-impact journals,” although highly cited initially, are soon forgotten. Especially in our time, when it is basically the editor of a journal and not the reviewers who decides what gets published – an editor who often has limited knowledge of the subject but knows what is ‘exciting’ – the major journals publish many papers that are composed of true data with contrived interpretations and very little long-term import. As scientists, we have to intellectually dissociate ourselves from fashion and journals, and focus on what is the actual content of a study, what the data really say (not what the abstract says!). We can then take pride and pleasure in work that reports an actual advance – I feel that this is the most important ability I tried to learn from my mentors, and I am trying to teach my students.

Thank You

Throughout my career, I have been generously supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the National Institute of Mental Health. I am grateful to both for their unflinching support. I have received several recognitions, all of them unexpected, among which I particularly cherish the Alden Spencer Award from Columbia University in 1993, the von Euler Lectureship from the Karolinska Institutet in 2004, the Kavli Award in 2010, the Lasker~deBakey Award in 2013, and – of course – the Nobel Prize. I am not sure I deserve any of these awards, as conceptual advances in science always represent incremental progress to which many minds contribute, but I immensely appreciate receiving them. Finally, I feel indebted beyond words to my family, my wife Lu Chen and my children Saskia, Alexander, Leanna, Sören, Roland, and Moritz, without whom I would be barren and rudderless, and who have been more considerate of me than I deserve, and finally to my ex-wife Annette Südhof who greatly supported me in earlier stages of my life, and to my brothers Markus and Donat Südhof and my sister Gudrun Südhof-Müller whom I appreciate more the older I get.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.