William Lipscomb – Nominations

William Lipscomb – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1976

The Boranes and Their Relatives

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 816 kB

William Lipscomb – Banquet speech

William Lipscomb’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1976

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

The award this year of the Nobel Prize in chemistry for research in pure inorganic chemistry is an important event. It is a reminder that we know even now considerably less about most of the chemical elements than we know of the chemistry of carbon or the chemistry of processes underlying life itself. It is also a reminder that the inorganic area characterized by these other elements is now being incorporated into organic chemistry and biochemistry.

On this occasion in which intellectual achievement is given its highest recognition, those of us who are being honored should remind ourselves that we are tall only because we stand on the shoulders of others: those who have gone before us showing the way, those who worked with us as our colleagues, those who supported our research giving us funds, and those who have honored us, including you, most of all.

Finally, I take special recognition of the truly international nature of science. As a personal note, I take pleasure in recalling the remarkable association that I have had with many other research groups in different countries throughout the world.

William Lipscomb – Interview

Interview transcript

Welcome to this interview, Professor William Lipscomb. You were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 25 years ago and it’s quite a long time, and I suppose that you have a long perspective on your field, and I wonder first if the Nobel Prize has changed the path of your life.

William Lipscomb: Well, I didn’t stop research, as some Nobel Prize winners do, I kept going. The direction of my research changed fairly abruptly though, not because of the award of the Nobel Prize but in 1964, the National Science Foundation, the inorganic branch, decided that I wasn’t going anywhere and they cut off all my research and I had already began to be interested in chemistry towards the biological side as well as in inorganic chemistry and so I was therefore required to change my field.

I understand. Were you of the same opinion in ’64 that the field is finished now and I have to move?

William Lipscomb: Absolutely not. Absolutely not. The field has grown enormously. The field of structure and bonding, and how atoms are held together to make chemical compounds has received a great deal of work and understanding and extended particularly towards how the molecules react, how they transform to other species, and even in recent years there has been a great transformation of computational chemistry and theoretical chemistry which allows one to predict structures, to guess reactions, almost predict reactions, so I think that will continue to improve.

What does it mean for our understanding of nature, that you can understand how material is structured on this level?

William Lipscomb: The problem is how do molecules react, because if you want to transform a molecule into something useful or something that you’re interested in, it helps a lot to have the structure because you can tell where the reactivity parts are, where you can change the molecule most easily, especially if you know the structure and then if you know how the charges on the atoms change. You can then make predictions about the reactions and do the transformations that previously were only trial and error. Now you can, with a purpose. That means you can explore much more complex systems, much more complex reactions.

How do you get this kind of self-confidence that you can believe that my interpretation and my idea is right? Even if everybody around you says no it must wrong.

William Lipscomb: Well, in order to make one of these kind of discoveries, you have to have read a lot, you have to know a lot and you have to suddenly, or maybe not suddenly, but gradually see something that’s different, that is implied or something that’s wrong, as I did in the case of the hydrides, I perceived it was wrong, but you then have to criticise it yourself before you test it or present it and as your confidence grows – it may take a long time, it may take 10 minutes, it may take years to develop your own confidence in these things – and sometimes you are wrong.

What is bad is to publish something that’s not very interesting …

What is bad is to publish something that’s not very interesting …It’s very important, that I learned from Linus Pauling, that it’s not a disgrace in science to publish something that’s wrong. What is bad is to publish something that’s not very interesting and so I learned from him that you really, he said once to me: It’s not what you can look up somewhere that counts, it’s what you really know that counts and if you know that, then that’s the basis for your discovery, and you won’t be shaken out of it if you have developed a certain amount of confidence and if you make some discoveries, then you can go on to make others and that is a criterion that we really believe that people who are creative remain creative. Now sometimes they don’t change areas, sometimes they are refining what they did earlier, but they’re still being creative.

I would like to ask you about something else. Besides being a chemist, you are also a performing musician.

William Lipscomb: Yes.

What instrument do you play?

William Lipscomb: I play the clarinet.

Yes, and what kind of music?

William Lipscomb: It’s mainly classical music and it’s mainly chamber music. You see, my mother taught me of the voice; my sister was a composer. She studied with Mademoiselle Boulanger, the famous teacher of composers, so there’s a lot of music in the family and I found it a very important part of my life.

Yes. Why?

… if you are playing chamber music, it’s not possible to think about chemistry …

… if you are playing chamber music, it’s not possible to think about chemistry …William Lipscomb: Because there are two things – one is that I sometimes get too wound up in my chemistry, but if you are playing chamber music, it’s not possible to think about chemistry. You’re too busy and so it was a diversion. But it was much more than that because playing music, even if it’s written, is still a creative art because the notes have to be phrased properly and the structure of the piece you have to imagine yourself and sometimes it’s different from what the composer meant, but you are creating things there and it’s the same kind of creative processes that we use in science. The scientific method, as people usually think of it, is not such an orderly process.

No. What is it?

William Lipscomb: Well, it’s a conjecture, or our guess, and then you set about first to test it to see whether it’s right and then you set out to prove it’s wrong and these are the processes but getting the original idea is something that involves your intuition. It isn’t so explicit and it isn’t the usual scientific method that people think about.

Well, one of your PhD students, actually the first one – Roald Hoffman – that you named before, also another prize winner, he wrote that one thing is certainly not true, namely that scientists have some greater insight in the workings of nature than artists.

William Lipscomb: That’s right, that’s right. And he knows that too because he is a poet and also a playwright now in addition to his science, he continues his science, Roald Hoffman, but he knows this kind of area but it’s really quite true. I think the intuitive processes of discovery are the same, very much the same in the arts as in the sciences.

But what kind of knowledge about nature you can get from arts?

William Lipscomb: From art?

Yes. Can you do it?

William Lipscomb: The artist must ask you to think of the world in a different way, and sometimes it’s a more abstract way, sometimes it’s a completely different kind of colouring. Sometimes it’s a very nice balance thing and sometimes it’s very disorganised but it’s a business of an artist to tell you something that’s different about what you see and what you feel, but this is true of science. A discovery in science is something which, if you know it, nobody else knows it if it’s yours and you have to show how it is and especially if it’s a very nice discovery, an important discovery. The first thing that happens is people will say, oh it’s wrong, no, it’s all been done before, it’s not worth doing. You know, when you hear that, then you say, oh I might have discovered something very interesting.

If we go back in time to the start of your career, what made you enter science in general?

When I was 11 years old, my mother bought me one of those chemistry sets …

When I was 11 years old, my mother bought me one of those chemistry sets …William Lipscomb: When I was 11 years old, my mother bought me one of those chemistry sets and I stayed with it. My father was a doctor. I went to the drug store to buy chemicals to enlarge the set, to get other chemicals, and I had some very dangerous ones that you cannot buy now because of the regulations and I did all my experiments at home. When I came to high school two things happened. One is the instructor said: Yes you can take chemistry but you already know enough. All you have to do is show up for the final examination, you don’t have to do anything else.

So I did some research and the second aspect is that when I left the high school, I graduated, I gave my chemistry set to my high school. It more than doubled what they had already, as I had a pretty big set, so I was very interested in chemistry from very early days. And I tried to imagine how the molecules were really behaving in terms of structure and so on.

What do you think of students, that they’re coming to science now, to the university? What would you advise them to choose?

William Lipscomb: Oh, they should choose to study something they’re really interested in and then learn to do it well. That’s exactly what I encourage in one; somebody is working for me and says I want to work on something else, I say you do it. Whether it’s a different field, completely different field, or whether it’s a different development and for a rather small number of my very best students, I have allowed them or encouraged them to find their own research problems and take them with them themselves to their new positions, to get a jump on the tenure situation.

Oh I see, so the motivation is coming from inside.

William Lipscomb: Exactly. I try to have them ask what their motivation is, what they’re really interested in, what they would like to be doing some years from now and encourage them to do it.

At the same time, science has become a more and more collective enterprise but what you’re pointing out is that it depends on how creative you are as an individual if you’re making progress.

… you need to try to imagine what is going on …

… you need to try to imagine what is going on …William Lipscomb: Yes, that’s right because although you have collective, you have in my area, for example, doing protein structure work which is what I’m doing now to determine the structures of proteins and to try to figure out how enzymes speed up reactions by such large factors, that’s one of the things. Or how enzymes are regulated so they don’t run away with the metabolism on a molecular basis, that’s what I’m trying to do but there, I think, you need to try to imagine what is going on and you also need a fairly large group of people working to do all the things that need to be done.

It reaches its zenith in the case of the particle accelerators, the physicists who need very large amounts, but there’s some group of people who have to, or person who has to lead, who has to set the agenda to say what particles you’re going to work on, what enzymes are you going to study. It’s a very important choice and so I think that the role of individual thought is also present in these large group enterprises that you refer to.

This is the role of the leader.

William Lipscomb: The role of the leader, or the leader could be someone who is not the real leader, not the one who gets the money, but that may be the intellectual leader, maybe one of the students. It can be and it has happened.

So you can compare the leader of a research group to a conductor in an orchestra?

William Lipscomb: Oh yes. Yes, that’s an interesting comparison. A lot of people think the orchestra is playing and the conductor doesn’t do very much but the conductor’s the person that gives shape to the music, gets the phrasing, and if he has really fine musicians in solo spots, the question is does he try to help them phrase, or does he let them go? He just decides that on the spot, depending on the musicians, sometimes he’s in control, sometimes he lets them be in control and there are interesting times because there’s a big difference among conductors. Some are very easy to understand and play under and some are very difficult and it’s the same for research groups, I think.

Thank you very much for the interview.

William Lipscomb: Thank you. Thank you for inviting me here.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

William Lipscomb – Other resources

Links to other sites

Obituary from Harvard University

Press release

18 October 1976

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the 1976 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to

Professor William N. Lipscomb, Harvard University, USA,

for his studies on the structure of boranes illuminating problems of chemical bonding

CHEMISTRY PRIZE FOR THE STRUCTURE OF THE BORANES

The studies for which William Lipscomb has been awarded the Nobel Prize are related to the chemistry of boranes. “Boranes” is the now accepted name for boron hydrides, i.e. the compounds of the element boron with hydrogen. There are a great number of boranes but very little was known about them for a long time. As a rule they must be studied at a very low temperature, they are usually unstable and chemically aggressive, explosive and toxic. For a long time no one really knew how the borane molecules are constructed and it was obvious that the conditions necessary for bonding were very different from those already known in other fields of chemistry.

One might suppose that the bonds between the atoms of the boron hydrides were similar to those between the atoms of hydrocarbons. In the latter, a pair of electrons are generally the bonding agents between two neighbouring atoms. However, boron has not as many bonding electrons as carbon and therefore all the bondings cannot be of this type. One type of bonding which might remedy this lack of electrons was suggested in 1949 but it was not until Lipscomb’s works from the beginning of 1950s onwards that the problems in borane chemistry could be satisfactorily solved. Not only has Lipscomb studied the pure electrically neutral borane molecules but he has also investigated charged borane molecules i.e. ions, and other molecules closely related to the boranes.

Lipscomb has tackled the problems with skillfull topological methods enabling him to identify the possible combinations of feasible types of bonding. With his fellow scientists he has determined the geometric structures by means of X-ray diffractions and by using modern quantum mechanical calculations has been able to determine and, in many cases, predict the stability and reactions of the molecules under varying conditions. Knowledge of the great subject field, covering the boranes and related chemical compounds, has thus been enormously enriched, at the same time as scientists have gained a deeper insight into the nature of chemical bonding.

Lipscomb has tackled the problems on a broad front, working in a little known field that is difficult to penetrate, and he has been the leading figure in the advances made there. The breadth of Lipscomb’s scientific achievement is also demonstrated by the eminent work he has done in other fields of chemistry. To mention but one, he has made notable findings in studies of the structure and mechanisms of enzymes.

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Professor Gunnar Hägg of the Royal Academy of Sciences

Translation from the Swedish text

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

This year’s Nobel Prize for Chemistry has been awarded to Professor William Lipscomb for his studies on the structure of boranes illuminating problems of chemical bonding.

A couple of days after the announcement of the chemistry Prize, a Swedish newspaper carried a cartoon by a wellknown Swedish cartoonist showing an elderly couple in front of their TV. The legend ran: “Can you remember ever having seen a borane, Gustav?” This question is quite proper, indeed. Gustav and his wife certainly had never seen a borane. Boranes do not exist in nature and can hardly be found in other places than chemical laboratories.

The name borane is the collective term for compounds of hydrogen with boron, the latter element forming part of among other things boric acid and borax. A great number of boranes and related compounds are known, and it is this whole group of substances which has been studied by Lipscomb. In the eighties of the last century it was understood that such compounds exist in the gas mixture that is formed when alloys between boron and certain metals are decomposed by acids. But it was only from about 1912 that the German chemist Alfred Stock succeeded in producing some pure boranes.

The structures and bonding conditions of boranes remained, however, unknown until about 1950, and it is not without reason that they have been considered problematical. The experimental study of the boranes has been very difficult. They are in most cases unstable and chemically aggressive and must, therefore, as a rule be investigated at very low temperatures. But it was still more serious that their structure and bonding conditions were essentially different from what was known for other compounds. Stock had found borane molecules that, for example, consisted of in one case two boron and six hydrogen atoms and in another case ten boron and fourteen hydrogen atoms. But when the object was to determine how these atoms are bound to each other, i.e. the appearance of the molecule, and also the nature of the bonds which keep the atoms together within the molecule, one was left in the dark for many years. One might suppose that these bonds were similar to those between the atoms in the hydrogen compounds of carbon, for instance in the hydrocarbons in liquefied petroleum gas. In these, the bond between two neighbouring atoms usually involves two electrons, an electron pair. However, boron does not have as many bonding electrons as carbon and, therefore, all the bonds cannot be of this type. A new type of bond, where two electrons co-operate in binding three atoms together, and which thus can master this electron deficiency, was proposed in 1949 but it was not until the researches of Lipscomb from 1954 and onwards that the problems of borane chemistry could begin to be solved satisfactorily.

Lipscomb has attacked these problems through skilful calculations of the possible combinations within the molecules of conceivable bond types and he has together with his collaborators determined the geometrical appearance of the molecules, above all using X-ray methods. But he has proceeded much farther than that in illuminating the binding conditions in detail through advanced theoretical computations. Thus it became possible to predict the stability of the molecules and their reactions under varying conditions. This has contributed to a marked development of preparative borane chemistry. These studies by Lipscomb have not only been applied to the proper, electrically neutral, borane molecules but also to charged molecules, i.e. ions, as well as other molecules related to the boranes.

It is rare that a single investigator builds up, almost from the beginning, the knowledge of a large subject field. William Lipscomb has achieved this. Through his theories and his experimental studies he has completely governed the vigorous growth which has characterized borane chemistry during the last two decades and which has given rise to a systematics of great importance for future development.

Professor Lipscomb,

You have attacked in an exemplary way the very difficult problems within an earlier practically unknown field of chemistry. You have worked on a broad front using both experimental and theoretical methods and the success of your efforts is shown by the fact that your results and your views have governed the recent development of borane chemistry.

In recognition of your services to science the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences decided to award you this year’s Nobel Prize for Chemistry. To me has been granted the privilege of conveying to you the most hearty congratulations of the Academy and of requesting you to receive your prize from the hands of his Majesty the King.

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1976

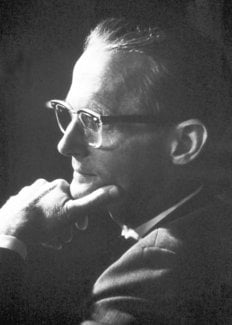

William Lipscomb – Biographical

Although born in Cleveland, Ohio, USA, on December 9, 1919, I moved to Kentucky in 1920, and lived in Lexington through my university years. After my bachelors degree at the University of Kentucky, I entered graduate school at the California Institute of Technology in 1941, at first in physics. Under the influence of Linus Pauling, I returned to chemistry in early 1942. From then until the end of 1945 I was involved in research and development related to the war. After completion of the Ph.D., I joined the faculty of the University of Minnesota in 1946, and moved to Harvard University in 1959. Harvard’s recognitions include the Abbott and James Lawrence Professorship in 1971, and the George Ledlie Prize in 1971.

The early research in borane chemistry is best summarized in my book “Boron Hydrides” (W.A. Benjamin, Inc., 1963), although most of this and late work is in several scientific journals. Since about 1960, my research interests have also been concerned with the relationship between three-dimensional structures of enzymes and how they catalyze reactions or how they are regulated by allosteric transformations.

Besides memberships in various scientific societies, I have received the Bausch and Lomb honorary science award in 1937; and, from the American Chemical Society, the Award for Distinguished Service in the Advancement of Inorganic Chemistry, and the Peter Debye Award in Physical Chemistry. Local sections of this Society have given the Harrison Howe Award and Remsen Award. The University of Kentucky presented to me the Sullivan Medallion in 1941, the Distinguished Alumni Centennial Award in 1965, and an honorary Doctor of Science degree in 1963. A Doctor Honoris Causa was awarded by the University of Munich in 1976. I am a member of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A. and of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences and Letters.

My other activities include tennis and classical chamber music as a performing clarinetist.

William Lipscomb died on April 14, 2011.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.