John Pople – Other resources

Links to other sites

‘Sir John Pople, Gaussian Code, and Complex Chemical Reactions’ from DOE R&D Accomplishments

Obituary from The New York Times

John Pople – Interview

Interview transcript

I’m very pleased to be sitting here with Professor John Pople at the Lindau meeting, the 50th anniversary of the Nobel Prize Tagungen in Lindau. And let me first ask you, Professor Pople, how did you come to end up in science? Was there a family background in science? What started you?

Professor John Pople: My family has no scientific background. As a child I lived in a small town in the West of England. My father was a shop keeper. He owned and ran the men’s clothing store in this town. My mother’s family were mostly farmers from different parts of England. So I had no professional scientific background in my family. As a child I did become extremely interested in mathematics at about the age of 11 or 12. I was by that time already keeping my father’s accounts, large sums to be added up in pounds, shilling and pence, which is quite complicated mathematics. And I became very facile in doing this sort of thing.

I used to make sometimes deliberate errors in mathematics classes so that I would not appear to be too smart …

I used to make sometimes deliberate errors in mathematics classes so that I would not appear to be too smart …But then at the age of 12, when I started being exposed to algebra in school, I became extremely fascinated and spent much of my time teaching myself at the age of 12 more advanced parts of mathematics. In fact, I taught myself calculus using an old book which I found in a waste basket and I took it out of the waste basket and read it from cover to cover. So by the age of 12 I was already actively thinking about mathematical problems. I was thinking about permutations and extending tables of factorials to non-integer values, various projects which I formulated and tried to solve, not always successfully, but I was doing research projects in mathematics when I was quite young. So that was really my introduction to academic subjects. Actually at that age I was quite secretive about it. I did not tell my teachers that I had taught myself calculus. And for a while I was reluctant for this to be known, and I used to make sometimes deliberate errors in mathematics classes so that I would not appear to be too smart. One feels the pressure from one’s peers at that stage. But then after two or three years I sort of went public with this. Then the school authorities, this is at Bristol Grammar School which did have a very fine mathematics teacher, they told me that I should study for the scholarship exam for Cambridge. So I spent the last two or three years really preparing for this competitive intake at Trinity College Cambridge, which is where mathematicians tend to go in Britain, because they have a great history in development of mathematics.

So I went to Cambridge to take the scholarship examinations in the middle of the War, in 1942. At that time it was not too easy to go to University because almost all young men, I was 17 at the time, were conscripted into the army. But there was a programme for a small number of mathematics students to go to university, to Cambridge, to take a mathematics degree in a very short compressed period and then go into government service in some form of operations, research. This turned out to be a very successful programme. Some of the people who were in the programme before me that were older than me had made major contributions to the British war effort. Freeman Dyson was one such person. He was in exactly the same programme two years older than me, and he was in Cambridge between 1941 and 1943, and I think he went on to become an adviser to the air force in the latter part of the war. In my case I went to Cambridge in 1943 and by the time I’d completed my degree in 1945 the war was just ending so I never really did anything useful in the war time.

Turing did also at that time.

Professor John Pople: Well Turing, yes. I never met Turing. Turing was older than me. In fact, he was already a significant mathematician before the war, some very famous publications of his in the late thirties. Then right through the war of course he was a key figure in the code breaking operations and had an immense impact on the subsequent history, probably the most influential mathematician in modern times in that sense. Without his code breaking developments in the middle of the war it may well have gone the other way. It’s quite remarkable.

Then you went on to PhD studies?

Professor John Pople: Yes, in 1945 as the war was ending I was, the government didn’t quite know what to do with me because the war effort was winding down. So I was sent off into industry and I worked for the Bristol Aeroplane Company for two years, not doing anything very significant, until I could get back to Cambridge to start a research career. And so I returned in 1947. I spent one year doing sort of post graduate courses in all branches of applied mathematics and then it was after that that I decided to become a theoretical scientist. And at that point I picked on chemistry as a field that I would enter. But until then I had no background in chemistry. I’d given up chemistry at a quite early stage in high school. I decided this was a good opportunity. It turned out well.

But eventually you went to Canada for a while.

Professor John Pople: Yes, that’s correct. So from 1951 I became a research fellow at Trinity College and then two or three years later I actually became a faculty member in mathematics in Cambridge, so I taught mathematics from 1954. And it was at that time that I accepted an offer to go for two summers to the National Research Council in Ottawa. That is the point at which I became interested in nuclear magnetic resonance, largely because they were just starting there and they had some very interesting results and I had some ideas on it. So I spent two or three very fruitful years, spending the summers in Canada and going back and doing my teaching in Cambridge during the rest of the academic year.

I think that for me it started very early, NMR. And the book you wrote together with Schneider and Bernstein was, I think, to me the revelation of what NMR was. You laid the ground work for …

Professor John Pople: Yes, that was very … at that time, that was very well timed. The objective when we started, we started in 1957 I think, we said we would try to write a book which covered everything that had been written on nuclear magnetic resonance, high resolution nuclear magnetic resonance. And we actually attempted to refer to every paper on the subject. And we did that. We later discovered we’d missed two in the rush. But when the book was completed, it was only just possible because in the next six months the literature exploded. But it was early days. You could write interesting papers on very simple spectra of very simple organic compounds. We used to go down the corridor and knock on the door of an organic chemist and look along his shelf and say “Two three lutidine, let’s take that compound.” I’d go away and write a paper on it. The chemist would say “Well, what do you want that for?”.

Also you started working on quantum chemical methods and development on computational techniques?

I used to switch from one topic to another every two or three years …

I used to switch from one topic to another every two or three years …Professor John Pople: Yes. In the early days a felt that a theoretical chemist should really address all branches of chemistry and I did work as I told you on liquids, statistical mechanics or liquids. And I also started doing some work on quantum mechanics, there’s early papers on that by 1952. And then I did the nuclear magnetic resonance. So I used to switch from one topic to another every two or three years. But that became more and more difficult I think because as fields grow you need a great deal of technical expertise.

So in 1958 I took an administrative job which was for several years which I didn’t like very much. And when I gave that up I decided that I would return to full time research, with the main emphasis on quantum mechanics, of electronic structure of molecules, which is the most fundamental part of theoretical chemistry, basic understanding of how molecules, why molecules behave as they do. So that is the time at which I moved with my family to the United States. And the projects for which the Nobel Prize was awarded were started around that time.

The Gaussian program which just transformed quantum chemistry completely. Actually, you have seen the development of quantum chemistry problems, fairly a small group of people using it, now it’s a kind of standard technique. How would you see also the future development of quantum chemistry? Computers will soon evolve and you have some gigaflop or teraflop computers coming in the future. Will that per se also influence quantum chemistry or are there still more technical developments that are equal important?

Professor John Pople: Progress has taken place in both respects. One has been able to achieve more efficient or new methods, or more efficient ways of handling the same method. Certain theoretical computations may start off being rather expensive and hard to use except for very small molecules. But then one can do a lot of research on new mathematical schemes which will get the same answer with far fewer operations. That has been a major focus of work and that has enabled the techniques to be applied not only to very small molecules but to many molecules, larger molecules, and to begin to make really significant predictions about chemical behaviour. And that will certainly continue. Computers are clearly going to get faster and faster and we are continually working on ways of making our methods used to fewer and fewer multiplications to get bigger and bigger systems. So this is very much a development along the same path. You can never tell whether a totally new method will come in and demolish all existing procedures, but I don’t see it at the moment.

Would you see for example a kind of fusion of molecular dynamics and quantum chemistry?

Professor John Pople: Yes, that’s right. The good quantum chemistry, high level theories can still only be applied to systems of up to maybe 100 electrons. And it’s important to be able to examine systems which are in solution for example, where you have to take account of all the rest of the material. So there’s important work going on on kind of multiple techniques where you use a quantum mechanical study of, a good quantum mechanical study of a central part of a molecule or system, that you need to study carefully. And it’s surrounded by a solvent or the rest of a large protein or something which are simulated in a cruder fashion so that you can still get the general effects of the medium on the chemistry that’s going on.

At this meeting many things have also happened. Two days ago there was a joint announcement by groups from the States and Britain and other countries that have completed the sequence for 99 or 97% of the human genome. It’s regarded by many as a milestone in the human history, science history. And probably rightly so. I know that you take an interest also in biological systems and would you like to comment on these recent events that we have witnessed?

Professor John Pople: Yes, well that is certainly the complete knowledge of the human genome would be a big step forward. I think from a scientific point of view one may well desire to have the sequences of many more species before we can begin to really get a further understanding of evolutionary processes and how they have taken place. Biology is really a giant study in the history of particular chemical reactions which has gone on for three to four billion years over a complicated fashion. And the fundamentally interesting point is how did this come about and how did it develop in its various branches. And we’ve heard something of this of course in the talks this morning. So I think this is a big development. It’s clearly the way that the future of the science will go. I’m sure there’ll be the sort of political pressure to work primarily on the human condition rather than other species, which might be more informative, and on which one might be able to do it as was pointed out this morning, on which it might be possible to do more actual experiments.

You have had a lot of students over the years, what advice have you given them during their carreer?

… research is all about getting new ideas …

… research is all about getting new ideas …Professor John Pople: For my students? Well I’ve had a very fine set of students. I’ve always tried to advise them to handle research in an innovative but critical manner. It’s all about, research is all about getting new ideas. It’s always desirable to question existing ideas. It’s always desirable to formulate your ideas in as simple a fashion as possible, to test them as carefully and as fully as possible for the whole series of steps which I think constitute good research. And many of my students, I think, are very proud of their subsequent careers, have done very well. I’ve got to the age where I actually find myself going to dinners for retirement of people who were students of mine. So after one’s own retirement one starts attending other people’s retirements or 60th birthdays and all those things.

You are still active as a scientist.

Professor John Pople: Yes, I’m active part time. I no longer run a large research group but I do have some collaborations going and I am part of a commercial company which is in the business of distributing programmes of this sort. So that keeps me active, as well as attending Nobel functions which is a major part of one’s life.

That’s exciting. Thank you very much, Professor Pople.

Professor John Pople: Thank you.

Interview with John Pople by Sture Forsén at the meeting of Nobel Laureates in Lindau, Germany, June 2000.

John Pople talks about his family background, his exceptional interest in mathematics during the war; how moving to Canada fired his research in NMR (7:56); quantum chemistry and the development of computer techniques (10:34); his thoughts on the Human Genome Project (15:35); and his advice to young students (17:48).

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

John Pople – Photo gallery

John Pople receiving his Prize from the

hands of His Majesty the King.

Copyright © FLT-Pica 1998, SE-105

17 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46-8-13 52 40

Photo: Anders Wiklund

All 1998 Nobel Laureates on stage at the Stockholm Concert Hall. John Pople is fourth from left.

© FLT-Pica 1998 S-105 17 Stockholm, Sweden, telephone: +46 (0)8 13 52 40. Photo: Claudio Bresciani

Walter Kohn – Photo gallery

Walter Kohn receiving his Nobel Prize

from His Majesty the King at the Stockholm Concert Hall 1999

(a year later).

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1999

Walter Kohn received his Nobel Prize one year later, in 1999. Here all Nobel Laureates are onstage for the 1999 Nobel Prize Award Ceremony. Walter Kohn is fourth from left.

© The Nobel Foundation 1999. Photo: Hans Mehlin

Photo: Hans Mehlin

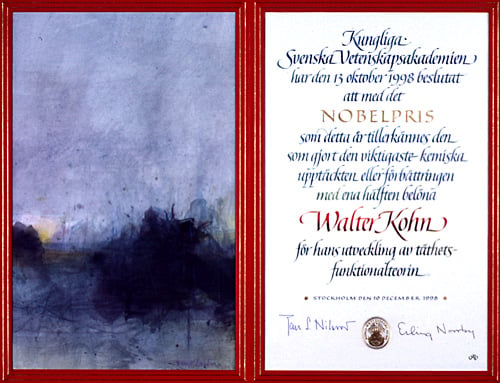

Walter Kohn – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1998

Artist: Bengt Landin

Calligrapher: Annika Rücker

John Pople – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1998

Artist: Bengt Landin

Calligrapher: Annika Rücker

John Pople – Banquet speech

John A. Pople’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 1998.

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highness, Ladies and Gentlemen,

On this occasion I have much to celebrate.

I rejoice in the opportunities I have had in many diverse branches of science over the past fifty years. Starting in mathematics, using fundamental principles of physics, aided by developing power of computer science I have seen the expansion of theory in many branches of chemistry and biology. Increasingly, science is being unified.

I rejoice in the magnificent group of students who have aided me over the years, without whose brilliance and dedication, little could have been possible. They have come from far afield. I am honoured by the presence of some tonight, including two who have made the longest journey from Australia and New Zealand to be with us at this ceremony.

I rejoice in the large community of quantum chemists, to which I belong. Over the years, we have worked closely together, freely exchanging ideas and inspiration. It is a great delight to me that a scientific career can lead to so many friendships among people from so many nations.

Finally, I rejoice in this occasion, this magnificent celebration of human culture. Over the past century, the Nobel Foundation has fashioned a unique focus for so many diverse, impressive achievements. I join this class of Nobel laureates with much humility.

For all of this, I am deeply grateful.

Walter Kohn – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, January 28, 1999 (a year later)

Electronic Structure of Matter – Wave Functions and Density Functionals

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 2.23 MB

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1999

John Pople – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1998

Quantum Chemical Models

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 759 kB

Walter Kohn – Interview

Interview with Professor Walter Kohn by freelance journalist Marika Griehsel at the 54th meeting of Nobel Laureates in Lindau, Germany, 2004.

Professor Kohn talks about being a non-chemist awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry and how it has affected his life; how the sciences differ (8:29); gives some advice to young students (9:29); talks about traumatic experiences during his childhood (13:13); his years in Canada (17:43); and how he initially came into science (22:40).

Interview transcript

Professor Kohn, thank you for seeing us today, it’s very nice to meet you. You got the Prize in Chemistry 1998 and that took a few … that was quite a number of years after you did your remarkable discovery. How have you dealt with this prize, this award and how has it, how has it affected your life?

Walter Kohn: I’ll answer this in two parts. I mean one is simply how has receiving the Nobel Prize affected my life and the other one is, the second part is how has the fact that I’ve suddenly been transformed into a chemist affected my life and it’s, in both cases really very positive. Insofar as the first half of your question is concerned I think most of my colleagues who have received a Nobel Prize have probably had the similar experience. The fact that you receive the Nobel Prize suddenly means that broadly speaking people take you more seriously suddenly and that means that if one has some principles, some convictions and is not totally satisfied with the world as it is, one now has …

… here is the leading country in the world, but look at its health system …

… here is the leading country in the world, but look at its health system …Let me first say an opportunity, but really in certain sense a responsibility to do something with it. Not to let it be. I mean whether one’s concern is for example as an American I’m very concerned about the fact that here is the leading country in the world, but look at its health system. So health system is on the one hand in many areas the best in the world, on the other hand, if you look at the fraction of people, including millions of children who are getting very poor, sometimes no health care, it’s shocking. So as an example of something that I felt very upset about for many years.

Do you speak out about that?

Walter Kohn: Yes, you know, I speak out on it and, and the same about several other areas that concern me, so.

And during your speech in -98 you said that for example working for peace is something of importance.

Walter Kohn: Yes, and I continue to do this quite actively. I’ll just mention something very concrete, I’m a research Professor at the University of California, the Santa Barbara Campus, and the University of California is, has been managing the two, the two nuclear weapons laboratories in America, I think I’m correct in saying that every advance in the effectiveness of nuclear weapons – and one has to stop for a moment and ask oneself whether the word “advance” is the appropriate word – was done under the management of the University of California. It’s my University. It bothers me a lot and so the …

This management of the weapons laboratories by the University of California with some little glitches and some modifications is negotiated typically for a period of five years and then in the past has always been renewed. But it has to go through a renewal process. So the renewal process is just in progress now and I’ve spent a lot of time on this. I have spoken not only on my Campus but I’ve had a video made and the video has been used in Los Angeles at UCLA and so I had this what I call the opportunity and I personally felt the responsibility to speak up on this question.

And the other part is that you got it for chemistry, but you are not a chemist.

Walter Kohn: No I, yes that’s quite correct and well, that’s the situation, I’m actually very comfortable with it. Chemists do use my work extensively and they appreciate it and they are, because they appreciate it they are without exception very friendly towards me. They would be in a position extremely easily to embarrass me terribly, but no-one has ever tried that. I can tell you a slightly amusing story.

The day after I received the Prize of course it was quite a sensation in my little town in Santa Barbara, so I walked across the Campus and two students, two women students, are walking in the opposite direction, and they must have seen my picture somewhere, perhaps in the student newspaper, and so one of them turns around and comes back and says to me “Are you the guy who won the Nobel Prize?” and I said “Yes, I am” and so they both gave me a very friendly hug and then they kept going again, but then one came back again and said “Do you mind, we are just going to a chemistry exam, can we ask you a question?”

… at a certain theoretic level chemistry and physics are very close to each other …

… at a certain theoretic level chemistry and physics are very close to each other …So yes I was in a very tight spot! So I said “well try me” and I started praying very hard because I knew that the more elementary the questions would be the less likely that I could answer them! And so then this one young woman began to ask a question and then I recognised an interesting fact. You see my … the fact that I got the Nobel Prize in Chemistry reflects the fact that at a certain theoretic level chemistry and physics are very close to each other, but also at the lowest level they’re very close to each other and these girls didn’t really know the difference between physics and chemistry. So the question they had for me was in fact a physics question. So I gave them a brilliant answer! They were very impressed.

Is it that these areas that you getting the Prize in, so to speak, maybe they do overlap more and more in the modern scientific world?

Walter Kohn: Yes, I would say yes, but I would not go along with some kind of world picture that all sciences will become unified. I think different sciences, and of course each science evolves over time, but by and large they do have their own characteristics which differ, and I personally think that’s for the good because then science as a whole is enriched by this difference. Vive la difference!

If you advise students today at the Campus, or people who are … who would listen to this interview who want to go into scientific research, what would you give them, what kind of advice would you give them?

Walter Kohn: First of all I would like to get to know the person a little bit before I offer any advice, because promising young scientists are already rather exceptional people and they are all different from each other and …

Then a specific quality that you have to have, do you have to endure long nights of hard work and days?

Walter Kohn: Well, many yes, and some no. So I wanted to make a caveat before I say anything, because what I say is perhaps broadly sensible, but there will be some cases where it will be absolutely the wrong advice, and well let me think about this, I’d say perhaps two or three words of advice. Number one: Be prepared for some great excitement and great personal rewards but mostly disappointments, and you must last through disappointments and you have to be prepared for them. So that’s one piece of advice.

… I myself feel very much like a global citizen and it’s one of the best parts of my life …

… I myself feel very much like a global citizen and it’s one of the best parts of my life …Another piece that I would offer is, but again I would come back and say, I know people who would not say that, but in general I think scientists have a great opportunity to combine their intellectual or in some cases mechanical abilities on the one hand with playing a useful role in society, and whether it’s their town, or their country or whether it’s global, and of course scientists are a very global group and of course Nobel himself sort of highlights this globality of science, and I think I myself feel very much like a global citizen and it’s one of the best parts of my life. I mean I’m just coming from two hours conversations with students from all over, you know, the kind of students that come here literally all over the world and it’s very few things that are more richer, that richer experience.

Professor, you said you, you know, the scientists feel like a citizen of the world often and certainly one can describe you as a citizen of the world. You were born in Austria, but your childhood was made traumatic as you had to flee during the Nazi takeover of Austria. Could you tell us something about that?

Walter Kohn: I had traumatic experiences in my childhood. The traumatic experiences were related with the so-called Anschluss, the joining of Austria to Germany during the Hitler time in 1938. Before that, looking back at least, I feel I had a generally good childhood. So my problems were … many people of course suffered under the Hitler regime, my family and I suffered like all other people who were in the same situation because of our religion. We were Jewish. Now the … was that traumatic? Yes, it was terribly traumatic, I mean the entire family was totally uprooted, destabilised, maltreated, I was thrown out of my school in a day, as I remember, and so there were things of that sort. Now I want to say first of all that my parents did succeed to help both my sister and myself to emigrate, we both emigrated first to England, unfortunately they were unable to emigrate and they were eventually murdered.

I did not ever even think about returning, it was unbearable for me …

I did not ever even think about returning, it was unbearable for me …Both my sister and I had a wonderful experience in England, a family that we had not ever encountered personally had some business relationship with my father took us into their home and treated us as family members and were absolutely wonderful. My sister eventually returned to Vienna after she married an Austrian, another Austrian émigré. I did not ever even think about returning, it was unbearable for me, and after, so then I had bizarre experiences, in retrospect right I was threatened with extermination by the Austrians and Germans but on the other hand the English regarded me as a potential spy for the Germans, and in turn me and thousands of others who are close to years, and so I had bizarre experiences of this sort. Of course compared to the horror of people who had to stay behind I was in my personal body, so to speak, I was fortunate, the loss of my parents was of course disaster.

So after the years in England you went to Canada, you emigrated to Canada, or was sent to Canada. What happened there?

Walter Kohn: Well, in Canada I, together with I think approximately within five and ten thousand other people in similar situations, was put into an internment camp. You may wonder how did they happen to have this internment camp ready, well they had it ready because they arranged, the Canadians, with the British at the British request to build these internment camps in order to be prepared for the thousands of German prisoners of war they expected. Well the war didn’t go that way, in the initial period the British, the little British expeditionary force in France they were incredibly lucky to get away with their skin and they came back to Britain and I think a single prisoner came back with their skin, so there were these camps waiting and here were we, the suspected spy.

So, yes we were put in these camps and I want to say right away we were treated very humanely. It was sometimes difficult because there were a few real Nazis in there, a small minority, but they were very in the early phases of the war, the war was going splendidly for the Germans and so whenever there was a great victory on the East Coast, right, these people would have their celebrations, and of course the rest of us got very upset about this. So it was unpleasant, nothing really serious, nobody lost his life but few people lost a few teeth! Otherwise, there was a wonderful man there I encountered several times in my life these people that were there, this was a man by the name of Heckscher, a German art historian, and we encountered him as this dedicated person, very capable, very intelligent and he was going to establish a school in camp for young people like me. Himself was about 20 years older, in his late thirties, and he inspired respect by everybody including the officers who treated him pretty much as their equal. He was not Jewish but he had been … his family had been in the business of helping camp prisoner of war camp inmates for the second generation, his father had done this in the First World War and so he took over the family tradition. So he established a very good camp school.

There were some brilliant people in the camp and so I divided my time roughly half to studying and the other half we were given the opportunity, but not required, to do work of different kinds, so the work, I had two kinds that I liked best was making camouflage nets for the British Armed Forces, that’s very calming for the nerves, you stand there and you have sort of three movements that you learn in five minutes and then you repeat them tens of thousands of times and of course you no longer know you are doing this, and you can dream, whatever, talk to your neighbour. And the other activity in Canada, you will be surprised, was lumber work, cutting trees. So of course I mean from time to time we felt a little sorry for ourselves, I mean why are we in this camp and why can’t we go out and so on, but …

When did you set your heart on science then?

… a re-organised school which was exclusively for Jewish students and with Jewish teachers. Many of them did not survive …

… a re-organised school which was exclusively for Jewish students and with Jewish teachers. Many of them did not survive …Walter Kohn: Perhaps the most influential person was somebody I encountered after the Anschluss in Austria. I was expelled from my school, there was some temporary arrangements, complicated, I skipped them for a few months, the Anschluss was in March, next September some of us who had high grades in school were given the opportunity to enter into a newly organised, that’s not quite correct, but let me just say to enter into a re-organised school which was exclusively for Jewish students and with Jewish teachers. Many of them did not survive. The director was a physicist and so he directed the school and he taught physics. Then his Latin teacher was arrested and didn’t come back, and so the director who had taken Latin in school also taught Latin, and he didn’t know much Latin but he came into class with the books that were supposed to be read, some of the classic Latin poets, Ovid, Virgil, and a dictionary. So he taught us from the books and the dictionary …

Which way was he influencing you to become a physicist?

Walter Kohn: Well, he taught physics also. He influenced me both very much just admirable personality generally and inexplicably it was evident to me from the beginning that this man really knew science. Really understood science. Then about ten years later I found out that he had been an assistant of Einstein’s and he was an incredible man. I think without meeting him, and I had another very good teacher, a mathematician in the same school, without these two gentlemen I probably would not have become a scientist. My interests before that time, I was very enthusiastic about something but it wasn’t science, it was Latin.

Latin?

Walter Kohn: Yeah.

Sir I would like to say thank you very much and good luck, thank you very much.

Walter Kohn: Thank you, thank you for the questioning.

Thank you.

Interview with Professor Walter Kohn by freelance journalist Marika Griehsel at the 54th meeting of Nobel Laureates in Lindau, Germany, 2004.

Professor Kohn talks about being a non-chemist awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry and how it has affected his life; how the sciences differ (8:29); gives some advice to young students (9:29); talks about traumatic experiences during his childhood (13:13); his years in Canada (17:43); and how he initially came into science (22:40).

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.