Applying for jobs can be daunting, but there are simple ways for early-career scientists to ensure their applications stand out. Through the , Nobel Laureates…

© Nobel Media. Photo: Alexander Mahmoud

Almost 50 years later, Chalfie visited Canada as part of the Nobel Prize Inspiration Initiative and shared his experiences with young scientists. It turns out that many of the reasons he had initially decided not to continue with research were based on misconceptions.

According to Chalfie his first experience with science ended badly because he was too afraid to ask for help. The stories he’d heard about great scientists were of lone geniuses, who made their breakthroughs without the help of others. His conclusion was that, if he was cut out to be a scientist, he should be able to do his experiments entirely by himself.

“I felt that I had to do everything on my own, because asking for help was a sign that I was not intelligent enough,” Chalfie said. “I now see how destructive this attitude was, but then I assumed that this was what I had to do.”

Instead of asking questions and seeking guidance, he persevered on his own even when his experiments were repeatedly failing. Inevitably, his first research project didn’t lead to any results. “I tried doing experiments all summer, but nothing worked,” he said. “I did not enjoy failing and decided that a career in science was not for me.”

He instead went on to teach in a high school where he enjoyed interacting with students. It also meant that his summers were free and, when a fellow teacher introduced him to her friend at Yale Medical School, he found himself back in the lab. This summer job proved to be a revelatory experience. He set up his experiments with help from two other scientists, and this time they worked. Buoyed by his success, Chalfie gave up teaching and took up a full-time position in the lab.

However, this was by no means the end of his failed experiments. He has continued to experience disappointment throughout his time in the lab, though his attitude to failure has completely reversed. For him, anyone who strives for major discoveries will experience a lot of failures. And these failures aren’t just inevitable, they are important. They can take you in new directions, and reveal insights you weren’t expecting.

To illustrate this point, Chalfie tells the story of his co-laureate Osamu Shimomura. Shimomura was studying how organisms emit light, which they do using a variety of different mechanisms. However, he had great trouble in finding the mechanism used by a particular jellyfish species to produce a beautiful ring of green light. He tried repeatedly to extract the substance causing this green glow, but failed again and again. His extract simply didn’t light up.

He spent his days and nights thinking about what he was missing, sometimes going out in a rowing boat so he could think without being disturbed. In the end the answer appeared by accident. One night when he poured the extract away, the sink lit up with a bright blue flash. Seawater from an aquarium overflow was running into the sink – he realised that the seawater had caused the luminescence. Because the composition of seawater is well known, he easily discovered that the luminescence was activated by calcium ions. He was able to purify the protein which is responsible for the light, and it became the first calcium indicator.

However, one mystery still remained. The jellyfish produced green light, yet Shimomura’s sink had glowed blue. He continued with his experiments and found a second protein which converts the blue light into green. We now call this green fluorescent protein, and it is one of the most important tools in biological research. Researchers use it to watch processes that were previously invisible, such as the development of nerve cells or the ways which cancer cells spread. It is this protein, GFP, which gained Chalfie and Shimomura the Nobel Prize, along with co-laureate, Roger Tsien.

Shimomura’s story is a complete contradiction of Chalfie’s early assumptions about how science works. He had believed that scientists were always purposeful in their experiments and knew where they were going. The reality, he discovered, is that many discoveries are accidental, and often come before the hypotheses. The important step comes next – recognising the significance of those discoveries and deciding what to do with them.

These videos were filmed at a Nobel Prize Inspiration Initiative event in Canada, delivered in partnership with AstraZeneca.

First published in November 2019

Applying for jobs can be daunting, but there are simple ways for early-career scientists to ensure their applications stand out. Through the , Nobel Laureates…

© Nobel Media. Photo: Alexander Mahmoud

Early-career scientists face difficult decisions when building their career in research, and indeed about whether a career in research is right for them at all.…

© Nobel Media. Photo: A. Mahmoud.

Hard work has been part of every laureate’s journey towards the Nobel Prize. Françoise Barré-Sinoussi spent time in the lab on the morning of her…

Elizabeth Blackburn speaks at a Nobel Prize Inspiration Initiative event

Your Majesties, your Royal Highnesses, ladies and gentlemen; on behalf of Shinya Yamanaka and myself, may I express our profound gratitude to the Karolinska Institutet and to the Nobel Foundation for this pre-eminent honour bestowed on us at this time.

Shinya Yamanaka and I must be more different than any other previous co-recipients of the Physiology or Medicine award. Shinya Yamanaka was born in the year of my main finding, and we have never worked together or on the same material; yet we share our great wish that our contributions may help to alleviate human suffering in a similar way.

For my part I have worked all my life with eggs and embryos of frogs. Compared to other small animals, these have figured prominently in the world of literature. They served as a chorus in a play by Aristophanes, The Frogs, which won first prize when first performed in 405 BC. A.A. Milne’s Toad of Toad Hall was a very benign Lord of the Manor in his river community. Hilaire Belloc wrote,

“Be kind and tender to the frog,

and do not call him names.

A shiny skin, a Polly‐wog,

or Gape‐a‐grin, a toad gone wrong,

The frog is justly sensitive

to epithets like these.

No animal will more repay

A treatment kind and fair.”

I myself have been a major beneficiary of the view that no animal will more repay treatment that is kind and fair.

Shinya Yamanaka’s work has involved mice and human cells, and advances the prospect of providing new cells or body parts for patients. This concept goes back in history for a long time. The earliest example known to me, of replaced body parts, is exemplified by a Mayan skull, dating back to 1400 BC. In this skull, false teeth made of stone, had been implanted. This was not just to improve appearance in the presumed after-life. The reaction of the jaw-bone showed that the false teeth had been hammered in in life. (Perhaps, at that time, an extract of the coca tree, of South America, now used by dentists as novocaine, had already been discovered.)

Although body part replacement is not a new concept, the practice of reversing the process of cell differentiation to an embryonic state to form new cells of different kinds has become a realistic prospect during the last half century. This raises the possibility of giving people new cells of their own genetic kind, and hence, without immunosuppression, to replace cells worn out by age or disease, a hope of the new field of regenerative medicine.

Starting in my case with no therapeutic benefit in sight, we are truly grateful to our immediate families and close colleagues, Ron Laskey for me and Kazutoshi Takahashi for Shinya Yamanaka, for their selfless co-operation and support.

We thank our hosts immensely for this truly unique experience provided by a spectacular week, and also for this magnificent banquet.

Watch a video clip of the 2012 Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine, Sir John B. Gurdon, receiving his Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 2012.

John B. Gurdon’s page at Gurdon Institute

Video

Video interview with Sir John Gurdon from University of Cambridge. In the interview John Gurdon talks about the research that revolutionised a field, his hopes for the future, and that now legendary school report.

Video kindly provided by University of Cambridge.

1 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon receiving his Nobel Prize from His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2012.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2012

2 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon after receiving his Nobel Prize at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2012.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2012

3 (of 24)

All 2012 Nobel Laureates on stage at the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony on 10 December 2012. From left: Physics Laureates Serge Haroche and David J. Wineland, Chemistry Laureates Robert J. Lefkowitz and Brian K. Kobilka, Medicine Laureates Sir John B. Gurdon and Shinya Yamanaka, Literature Laureate Mo Yan and Laureates in Economic Sciences Alvin E. Roth and Lloyd S. Shapley.

© Nobel Media AB 2012. Photo: Alexander Mahmoud

4 (of 24)

A bird's eye picture of the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in the Stockholm Concert Hall on 10 December 2012.

© Nobel Media AB 2012. Photo: Alexander Mahmoud

5 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon with family and relatives on stage after the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2012. From left: Edward Connolly, Serena Connolly, Aurea Connolly, Oliver Connolly, Sir John B. Gurdon, Lady Jean Gurdon and Caroline Thompson.

© Nobel Media AB 2012. Photo: Alexander Mahmoud

6 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon and Mrs Sedna Quimby Wineland, wife of Physics Laureate David J. Wineland, at the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 2012.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2012

7 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon delivering his banquet speech. © Nobel Media AB 2012. Photo: Helena Paulin-Strömberg

8 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon with relatives in the Golden Hall. From left: Oliver Connolly, Sir John B. Gurdon, Serena Connolly and Aurea Connolly.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2012

9 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon visits the Nobel Foundation on 12 December 2012 and signs the guest book. On this occasion, the Laureates retrieve the Nobel diploma and Medal, which have been displayed in the Golden Hall of the City Hall following the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony. The Laureates also discuss the details concerning the transfer of their prize money.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2012

10 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon takes a closer look at his Nobel Medal at the visit to the Nobel Foundation on 12 December 2012.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2012

11 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon delivering his Nobel Lecture The Egg and the Nucleus: A Battle for Supremacy in the Jacob Berzelius Lecture Hall at Karolinska Institutet, 7 December 2012.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2012

12 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon (right) is greeted by Bruce A. Beutler, 2011 Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine (left), at a reception at Karolinska Institutet, 7 December 2012.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2012

13 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon at the recording of the TV-program 'Nobel Minds' in the Bernadotte Library at the Royal Palace, 7 December 2012.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2012

14 (of 24)

Recording of the TV-program 'Nobel Minds', hosted by Zeinab Badawi, BBC World News, in the Bernadotte Library at the Royal Palace, 7 December 2012.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2012

15 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon (left) and Shinya Yamanaka (right) during their interview with Nobelprize.org on 6 December 2012.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2012

16 (of 24)

The 2012 Nobel Laureates assembled for a group photo during their visit to the Nobel Museum in Stockholm, 6 December 2012. Back row, left to right: Nobel Laureate in Physics Serge Haroche, Laureate in Economic Sciences Alvin E. Roth, Nobel Laureates in Chemistry Brian K. Kobilka and Robert J. Lefkowitz, and Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine Sir John B. Gurdon. Front row, left to right: Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine Shinya Yamanaka, Laureate in Economic Sciences Lloyd S. Shapley and Nobel Laureate in Literature Mo Yan. Not in photo: Nobel Laureate in Physics David J. Wineland.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2012

17 (of 24)

Portrait of Sir John B. Gurdon.

Photo: John Overton, Brown Group, Gurdon Institute

Kindly provided by Gurdon Institute

18 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon celebrating the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Photo: Peter Williamson, Gurdon Institute

Kindly provided by Gurdon Institute

19 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon's science report card from Eton College, 1949.

Photo: Sir John B. Gurdon

Kindly provided by Gurdon Institute

20 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon in his laboratory.

Photo: Wellcome Library, London

Kindly provided by Wellcome Library

21 (of 24)

Portrait of Sir John B. Gurdon.

Photo: Wellcome Library, London

Kindly provided by Wellcome Library

22 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon and colleagues at the Gurdon Institute's annual retreat.

Photo: John Overton, Brown Group, Gurdon Institute

Kindly provided by Gurdon Institute

23 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon on a kangaroo ball, investigating what it actually does feel like to be a frog.

Photo: John Overton, Brown Group, Gurdon Institute

Kindly provided by Gurdon Institute

24 (of 24)

Sir John B. Gurdon in his laboratory.

Photo: University of Cambridge, Gurdon Institute

Kindly provided by Gurdon Institute

Photo: Alexander Mahmoud

Photo: Alexander Mahmoud

Photo: Orasisfoto

Photo: Orasisfoto

Photo: Niklas Elmehed

Photo: Niklas Elmehed

Photo: Orasisfoto

Photo: Orasisfoto

Photo: Niklas Elmehed

Photo: Niklas Elmehed

Photo: Niklas Elmehed

Photo: Orasisfoto

Sir John B. Gurdon delivered his Nobel Lecture on 7 December 2012 at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm. He was introduced by Professor Urban Lendahl, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine.

Sir John B. Gurdon delivered his Nobel Lecture on 7 December 2012 at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm. He was introduced by Professor Urban Lendahl, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine.

The Egg and the Nucleus: A Battle for Supremacy: Lecture Slides

Pdf 5.51 MB

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 18.34 MB

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2012

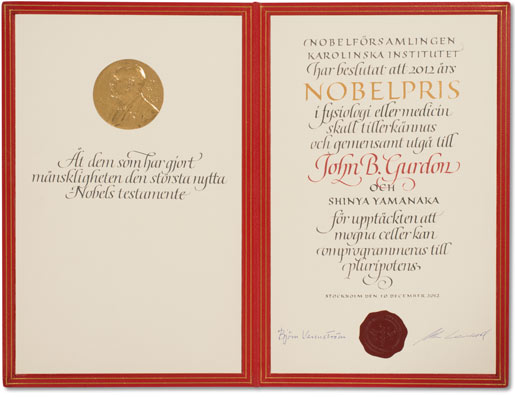

Calligrapher: Susan Duvnäs

Book binder: Ingemar Dackéus

Photo reproduction: Lovisa Engblom

Center for iPS cell Research and Application (CiRA) at Kyoto University

Shinya Yamanaka’s page at Gladstone Institute

UCSF Profiles: Shinya Yamanaka

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2012

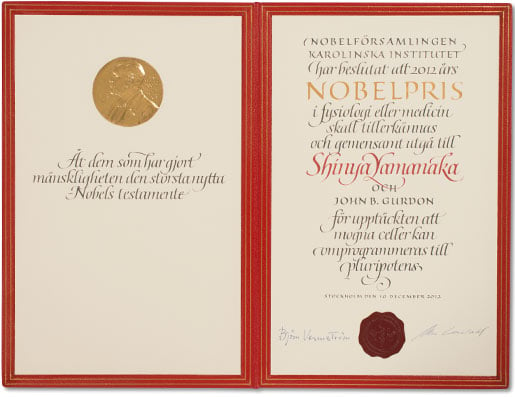

Calligrapher: Susan Duvnäs

Book binder: Ingemar Dackéus

Photo reproduction: Lovisa Engblom

Watch a video clip of the 2012 Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine, Shinya Yamanaka, receiving his Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 2012.