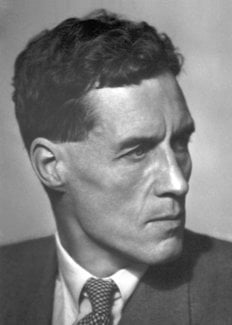

Patrick M.S. Blackett – Biographical

Patrick Maynard Stuart Blackett was born on 18th November, 1897, the son of Arthur Stuart Blackett. He was originally trained as a regular officer for the Navy (Osborne Naval College, 1917; Dartmouth, 1912), and started his career as a naval cadet (1914), taking part, during the First World War, in the battles of Falkland Islands and Jutland. At the end of the war he resigned with the rank of Lieutenant, and took up studies of physics under Lord Rutherford at Cambridge.

After having taken his B.A. degree in 1921, he started research with cloud chambers which resulted, in 1924, in the first photographs showing the transmutation of nitrogen into an oxygen isotope. During 1924-1925 he worked at Göttingen with James Franck, after which he returned to Cambridge. In 1932, together with a young Italian scientist, G.P.S. Occhialini, he designed the counter-controlled cloud chamber, a brilliant invention by which they managed to make cosmic rays take their own photographs. By this method the cloud chamber is brought into function only when the impulses from two Geiger-Muller tubes, placed one above and one below the vertical Wilson chamber, coincide as the result of the passing of an electrically charged particle through both of them.

In the spring of 1933 they not only confirmed Anderson’s discovery of the positive electron, but also demonstrated the existence of “showers” of positive and negative electrons, both in approximately equal numbers. This fact and the knowledge that positive particles (positrons) do not normally exist as normal constituents of matter on the earth, formed the basis of their conception that gamma rays can transform into two material particles (positrons and electrons), plus a certain amount of kinetic energy – a phenomenon usually called pair production. The reverse process – a collision between a positron and an electron in which both are transformed into gamma radiation, so-called annihilation radiation – was also verified experimentally. In the interpretation of these experiments Blackett and Occhialini were guided by Dirac’s theory of the electron.

Blackett became Professor at Birkback College, London, in 1933, and there continued cosmic ray research work, hereby collecting a cosmopolitan school of research workers. In 1937 he succeeded Sir Lawrence Bragg at Manchester University, Bragg himself having succeeded Rutherford there; his school of cosmic research work continued to develop, and since the war the Manchester laboratory has extended its field of activity, particularly into that of the radar investigation of meteor trails under Dr. Lovell.

At the start of World War II, Blackett joined the Instrument Section of the Royal Aircraft Establishment. Early in 1940, he became Scientific Advisor to Air Marshall Joubert at Coastal Command, and started the analytical study of the anti U-boat war, building up a strong operational research group. In the same year he became Director of Naval Operational Research at the Admiralty, and continued the study of the anti U-boat war and other naval operations: later in 1940 he was appointed Scientific Advisor to General Pile, C.M.C., Anti-Aircraft Command, and built up an operational research group to study scientifically the various aspects of Staff work. During the blitz he was also concerned with the employment and use of anti-aircraft defence of England.

In 1945, at the end of the Second World War, work was resumed on cosmic ray investigations in the University of Manchester: in particular on the further study of cosmic ray particles by the counter-controlled cloud chamber in a strong magnetic field, built and used before the War. In 1947, Rochester and Butler, working in the laboratory, discovered the first two of what is now known to be a large family of the so-called strange particles. They identified one charged and one uncharged particle which were intrinsically unstable and decayed with a lifetime of some 10-10 of a second into lighter particles. This result was confirmed a few years later by Carl Anderson in Pasadena.

Soon after this discovery, the magnet and cloud chamber were moved to the Pic du Midi Observatory in the Pyrenees in order to take advantage of the greater intensity of cosmic ray particles at a very high altitude. This move was rewarded almost immediately by the discovery by Butler and coworkers, within a few hours of starting work, of a new and still stranger strange particle, which was called the negative cascade hyperon. This was a particle of more than protonic mass which decayed into a (p)-meson and another unstable hyperon, also of more than protonic mass, which itself decayed into a proton and (p)-meson.

In 1948 Blackett followed up speculations about the isotropy of cosmic rays and began speculating on the origin of the interstellar magnetic fields, and in so doing revived interest in some 30-year old speculations of Schuster and H. A. Wilson, and others, on the origin of the magnetic field of the earth and sun. Although these speculations are not now considered as likely to be valid, they led him to interest in the history of the earth’s magnetic field, and so to the newly born subject of the study of rock magnetism.

Professor Blackett was appointed Head of the Physics Department of the Imperial College of Science and Technology, London, in 1953 and retired in July, 1963. He is continuing at the Imperial College as Professor of Physics and Pro-Rector.

Over the last ten years or so a group under his direction have studied many aspects of the properties of rocks with the object of finding out the precise history of the earth’s magnetic field, in magnitude and direction back to the earliest geological times. Such results, together with those of workers in many other countries, seem to indicate that the rock magnetism data supports strongly the conclusions of Wegener and Du Toit that the continents have drifted relative to each other markedly in the course of geological history.

The study is now being continued, directed to explaining the remarkable phenomenon that about 50% of all rocks are reversely magnetized. The experiments are directed towards deciding whether this reversed magnetization is due to reversal of the earth’s magnetic field or to a complicated physical or chemical process occurring in the rocks.

Blackett was awarded the Royal Medal by the Royal Society in 1940 and the American Medal for Merit, for operational research work in connection with the U-boat campaign, in 1946. He is the author of Military and Political Consequences of Atomic Energy (1948; revised edition 1949; American edition Fear, War, and the Bomb, 1949).

In 1924 he married Constanza Bayon; they have one son and one daughter.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Patrick M.S. Blackett died on July 13, 1974.

Patrick M.S. Blackett – Banquet speech

Patrick M.S. Blackett’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1948

The honour which has been bestowed on me by the award by the Royal Academy of Sciences of Sweden of a Nobel Prize for Physics gives me a feeling of deep satisfaction and personal pride. However, I like to think of the award not only as a recognition of my own scientific work, but as a tribute to the vital school of European Experimental Physics in which I was trained. The fact that all four Nobel prizes this year, and so many others in recent years, have been awarded to Europeans is surely a striking tribute to the astonishing vitality in the Arts and Sciences of our irrepressible, colourful, turbulent but war-scarred Continent of Europe. In spite of two world wars in thirty years – eleven years of my own life have been spent in warfare, either as a fighting man or as a scientific analyst of tactics and strategy – in spite of the immense devastation of the continent, the stream of new scientific discovery and of literary creation is still in as full flood as ever before. Now we find ourselves surrounded by rumours and threats of a third world war – a war which, if it comes, will be made more terrible than the last through the wonderful discoveries in atomic physics of the last decades. It is a curious comment on the unexpected twists of human history to note that Alfred Nobel used a fortune made through the invention and manufacture of explosives to endow most generously prizes for outstanding achievement in the arts of peace – and by so doing has stimulated and encouraged the great stream of discovery in pure physics, which culminated in the overwhelming devastation of Hiroshima. From this rostrum in previous years have spoken to you, as Nobel Laureates, nearly all the great scientists whose work has made the atomic bomb possible – the Curies, Rutherford, Bohr, Aston, Joliot, Lawrence, Hahn, to name only a few.

Pure science has proved the most dangerous of pursuits. In the field of destruction the wise words of J. J. Thomson are as valid as in the arts of peace: “Applied science makes improvements; pure science makes revolutions.”

The world today is facing the great problem of how to avoid a catastrophe made possible by the work of so many Nobel prizemen in Physics. It may be of interest to recall, however, that this is by no means the first time in history that mankind has felt the very basis of the established order threatened by the invention of a new weapon.

One such occasion was over 400 years ago. In 1494 Charles VIII of France crossed the Alps and rapidly destroyed, by means of artillery and Swiss infantry the military organisation of medieval Italy which was based on the fortified castle and the valor of the armoured knight. The poet Ariosto, contemporary of Machiavelli, wrote a poem dramatising the threat to the contemporary order. His hero, Orlando, embodiment of all the knightly virtues, meets an enemy with a firearm. When finally Orlando had triumphed, he took the offending weapon, sailed out into the ocean and plunged it into the sea exclaiming:

“Oh, Cursed device, Base Implement of Death

– – –

By Beelzebub’s malicious art designed

To ruin all the race of human kind – – –

Here lie for ever in the abyss below!”

It might not be inappropriate to utter again these four centuries old words on the hoped for future occasion when the United Nations finally consign the world’s store of atomic bombs to the depths of the ocean.

It is impossible to put the clock back – Machiavelli in his day could not stop the technological development which produced fire-arms – nor could Alfred Nobel stop those that followed his discovery of dynamite – nor can we stop the development of atomic energy. Technological progress and pure science are but different facets of the same growing mastery by man over the force of nature. It is our task as scientists and citizens to ensure that these forces are used for the good of man and not for their destruction.

Prior to the speech, Gustaf Hellström, member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, addressed the laureate: “Professor Blackett! If Alfred Nobel had been present tonight, he would with absolute certainty have been specially anxious to make your closer acquaintance in order to discuss with you the apparent contradiction which I touched on a few minutes ago. You have taken an active part in two World Wars; in the first as a young naval officer, in the second as the holder of one of the key positions in the British war-machine. After both wars you have turned to one of the sciences which made the devastation possible. You did this for the same reason as that which in times past, made many enter monasteries, better to serve their God. You retired to your laboratory, where you have proved yourself a master of physical technics. Now when you have for about a year extended your investigations in an attempt to explore the secrets of the Milky Way with the help of radio-astronomy, this is not to be interpreted as a form of escapism from a demoralized world, but as an effort to get closer to the mysteries of creation.”

Patrick M.S. Blackett – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 13, 1948

Cloud Chamber Researches in Nuclear Physics and Cosmic Radiation

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 689 kB

Patrick M.S. Blackett – Nominations

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Professor G. Ising, member of the Nobel Committee for Physics

Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen.

According to the statutes of the Nobel Foundation, the Nobel Prize for Physics may be awarded for “discovery or invention in the field of physics”. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in awarding this years’ prize to Professor P.M.S. Blackett of Manchester, for his development of the Wilson method and his discoveries, made by this method, in nuclear physics and on cosmic radiation, indicates by the very wording of the award, that its decision is motivated on both the grounds mentioned in the statutes. Particular weight may perhaps, in this case, be laid on the discoveries made, but these only became possible by Blackett’s development of the method and the apparatus.

Experimental research on the different kinds of rays appearing in nuclear physics has always been based to a great extent on the power of an electrically charged atomic particle, when moving at high speed, to ionize the gas through which it passes, i.e. to split a number of gas molecules along its path into positive and negative ions. Thus, one is able to count the number of particles by means of the Geiger-counter tube; such a counter being a special, very sensitive kind of ionization chamber, in which even a few ions produced by the ray are sufficient to release a short-lived discharge by an avalanche-like process.

But the whole course of the particle appears infinitely more clearly by the method invented by C.T.R. Wilson in 1911 and named after him. The radiation is allowed to enter an expansion-chamber, containing a gas saturated with water vapour. A sudden expansion of the chamber cools the gas, and cloud-drops are then formed instantly around the ions produced along the tracks of the particles. By suitable illumination these tracks can be made to stand out clearly as if they had been described by luminous projectiles. The “Altmeister” of modern nuclear physics, Lord Rutherford, once called the Wilson chamber “the most original and wonderful instrument in scientific history”.

But still, the immense value of the Wilson method for research purposes did not become really apparent until the early twenties, and the credit for this changed attitude was largely due to the work of Blackett, who has ever since been the leading man in the development of the method. Before 1932 his work dealt chiefly with the heavy particles, appearing in radioactive radiations. In 1925, he obtained the first photographs ever taken of a nuclear disruption, namely the disruption of a nitrogen nucleus by an alpha particle of high velocity; the photographs clarified quite definitely the main features of the process. In this investigation and others from the same period he also verified, by accurate measurements, that the course of a collision between atomic nuclei always follows the classical laws of conservation of momentum and energy, provided the energy value of mass, as given by the theory of relativity, is also taken into account. These two laws, together with the conservation law of electricity, i.e. that positive and negative electricity are always produced together in equal amounts, form a set of three fundamental principles of general validity.

Blackett was soon to give to these principles an unexpectedly rich content by new experimental discoveries. In 1932 namely, he turned his interest to the cosmic rays, which at sea level are mainly vertical. The Wilson cloud chamber had already begun to be used at different places for the study of these rays, but with very low efficiency, as only about every twentieth random photograph showed the track of a cosmic ray. This was due to the fact that the rays are disperse both in space and time, and they must pass through the chamber only about a hundredth of a second before or after the moment of expansion, if they are to give a sharp track. Nevertheless, Anderson had at the time succeeded in obtaining a few photographs, showing the temporary existence of free positive electrons. These electrons, on account of their strong tendency to fuse with negative ones, seemed to exist free in a space filled with matter, only as long as they move at a great speed.

Together with his collaborator Occhialini, Blackett now developed an automatic Wilson apparatus, in which the cosmic rays could photograph themselves: the moment of expansion was determined by two Geiger counters, placed one above and the other below the chamber and connected to a quick electrical relay in such a way, that the mechanism of the cloud chamber was released only when simultaneous discharges occurred in both counters, i.e. when a cosmic ray had passed through them both and thus in all probability also through the cloud chamber between them. In this way the efficiency of the Wilson chamber was multiplied many times over, and the method became of extreme importance in cosmic ray research.

Immediately after completing this apparatus, Blackett and Occhialini discovered, in cosmic radiation, positive and negative electrons appearing in pairs; their tracks were deflected in opposite directions by a superposed magnetic field and they seemed to start from some common origin, often situated in the wall of the chamber. Sometimes such tracks appeared in great numbers, whole “gerbes”, on the same photographic plate, demonstrating the existence in the cosmic radiation of veritable “showers” of positive and negative electrons. Shortly afterwards they established, in collaboration with Chadwick, that electron pairs are also produced by hard gamma rays, i.e. by the radiation of ultrashort wavelength emitted by certain radioactive substances; here the energy relations could be studied more closely than in the case of cosmic rays.

I shall try to give an idea of the great importance of these experimental results, even beyond the fact that they established irrefutably the existence of positive electrons. The discovery of the pair creation of electrons led, on the theoretical side, to the acceptance of two fundamental radiation processes of a reverse nature, which may be called transmutation of light into matter (represented by electron pairs) and vice versa. These processes take place within the framework of the three fundamental principles, just mentioned, regarding the conservation of momentum, energy and electricity: a quantum of light passing close to an atomic nucleus, may thus be transformed into a pair of electrons; but this is possible only if its energy at least equals the sum of the energy values of the two electronic masses. Since the rest mass of each electron corresponds to 1/2 million electron volts, the light must possess a frequency at least corresponding to 1 million electron volts. If there is an excess of energy (i.e. if the frequency of the light is still higher), this excess will appear as the kinetic energy of the two electrons created. Reversely, the meeting of two slow electrons, opposite in sign, results in their fusion and annihilation as material particles; in this process two light quanta, each of 1/2 million electron volts, are formed; these fly out from the point of encounter in opposite directions, so that the total momentum remains about zero (for even light possesses a momentum directed along the ray).

Blackett and Occhialini immediately drew these conclusions from their experiments and were guided in so doing by the earlier mathematical electron theory elaborated by Dirac on the quantum basis. The existence of the “annihilation radiation” was shortly afterwards established experimentally by Thibaud and Joliot.

These fascinating variations in the appearance of energy, which sometimes manifests itself as light, sometimes as matter, have stimulated the distinguished French physicist Auger to exclaim enthusiastically, in a monograph on cosmic radiation: “Who has said that there is no poetry in modern, exact and complicated science? Consider only the twin-birth of two quick and lively electrons of both kinds when an overenergetic light quantum brushes too closely against an atom of matter! And think of their death together when, tired out and slow, they meet once again and fuse, sending out into space as their last breath two identical grains of light, which fly off carrying their souls of energy!” (As a memory aid Auger’s metaphor is excellent; its poetical value is perhaps open to dispute.)

In the late thirties, Blackett continued his researches on the cosmic radiation and, using a still further improved Wilson apparatus, made extensive accurate measurements concerning the momentum distribution, absorbability, etc. of this radiation. By means of a new optical method he was able to measure extremely feeble curvature of the tracks, corresponding to electronic energies up to 20 milliard electron volts.

Professor Blackett. In recognition of your outstanding contributions to science, The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has awarded to you this year’s Nobel Prize for Physics for your development of the Wilson method and your discoveries, made by this method, in nuclear physics and on cosmic radiation.

In my speech, I have tried to sketch a few, and only a few, of your achievements and, more particularly, to give an idea of the fundamental importance of the discovery of pair creation. To me has been granted the privilege of conferring upon you the congratulations of the Academy and of inviting you now to receive your Nobel Prize from the hands of His Royal Highness the Crown Prince.