Transcript from an interview with Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio

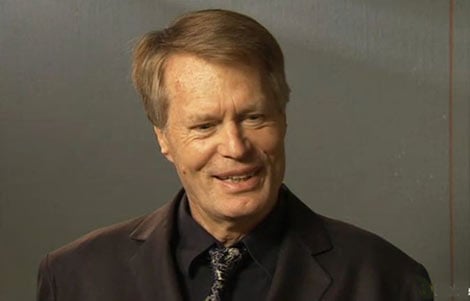

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio during the interview.

Transcript from an interview with Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio on 6 December 2008. Interviewer is Horace Engdahl, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy.

My name is Horace Engdahl, I’m the Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy and I have here beside me the Laureate for Literature of the year 2008, Jean-Marie Le Clézio. I will speak in English here – brings us immediately on the question of languages – we were asked by the director of the Nobel Web service to do that, and we have agreed. Of course your literary language is French, but apart from that, which are your languages? You speak English because your father was a British citizen, you also maybe speak Spanish because you’ve spent a lot of years in Mexico, and I’ve read somewhere that at a certain stage of your career you even learnt Embera Indian language, is that true?

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes, personally I belong to a dual culture because my family is from Mauritius, and as you may know in Mauritius the official language is English, the current language is Creole and the literary language is French, but I do not speak Creole, I speak very little Creole, I would not try to speak with you in Creole.

I wouldn’t understand, It’s no use!

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: So I’m used to shifting languages because my father used to speak to us, to my brother and I, he used to speak in English. He wanted us to be quite fluent in English, especially when he was trying to correct our behaviour, he would do that in English.

I see.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: And then of course I have lived in other countries, in Latin America, I learnt to speak what they call the Espanol /- – -/, the Spanish from the streets …

Oh, that’s not bad.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: … which is not literary Spanish. After that I lived for some time in the forest with the Embera Indians and I had to learn some Embera language which is totally different from the indo-European languages. So I …

Did you arrive speaking that language?

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes, I could speak fairly fluently, but they have also a literary language for tales or stories or for myths and this language I never spoke, it’s too complicated, so I spoke a very simplified Embera language, probably a rather simplified Spanish and a not too simplified but not too colloquial English. In fact I think I’m better in reading English than speaking English. My English is closer to the literary English and I’m not very familiar with jokes in English or with, you know, with small talk in English.

No. That’s always terribly difficult in any language that you’re not born with, I suppose.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes, yes, definitely.

It’s probably the sign of having really learnt a foreign language that you can laugh without looking at the people sitting beside you when you’re in a theatre for instance.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes.

I’m not sure I could do that in English either really, but coming to this question in another perspective, I feel that today there is a tendency in many parts of the world, in the Western world particularly, to look upon English as a vehicle language. It’s used more and more in all circumstances and there are several realms of research that have been completely taken over by English. In international conferences in the European Union etc we tend to be more and more mono-lingual and even if … I know that the French are defending their positions with a lot of conviction, they find it increasingly hard to do so. But it’s odd and it’s very apparent if you, like me, belong to a small group that has as one of its main tasks to study world literature, to read books from all over the world, to look at the development of universal literature in a broad perspective. It’s quite apparent that there is no such thing as a universal language in the world of literature. The only universal language in literature is translation, and you said earlier this morning on a press conference that for you it’s not only the French literature tradition that is the basis of your writing, but it’s also to a large extent books that you read in translations, English, American books, Scandinavian books, books from lots of other countries. Could you comment a bit on that? Which are the most important non-French writers that sort of belong to you through your literary schooling?

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: In fact I was told that in Sweden 80% of the population speaks English. This is amazing if you compare with the French people for instance. French speaking people or Spanish speaking people, where I suppose in Mexico they hardly speak, I would say 10% of the population will probably manage with English, but most of the population is ignorant of English. And for the French people it might be worse than 10% even, might find only 5% of people in France are able to have a conversation or read in English, so in that matter I would say that Sweden is probably ahead of all the countries.

On the other hand, what is amazing, which is very strange, is that the countries where most translations occur are not English speaking countries, for instance Korea is probably ahead of all countries for translations. Books are being translated from all languages, even very … even first novels or poems are translated into Korean very quickly, probably the same in Japan, and it’s very likely it would be close to that number in Sweden because Sweden has a good interest in translations.

I think it’s slightly more than 50% of all books published in this country that are translations in the literary field.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: And not all from English, they are from all languages, and on the contrary, when you go to the United States and look at the books stalls and you see what is sold in book stalls most, if not all, books are from English speaking persons. Very few books are translated, so it’s a kind of a paradox that the, what you would call the mono-lingual empire, is not interested at all in other languages, in other countries and trying to translate into this language.

No I think that …

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: And on the other hand all the countries where English is not so much spoken are the countries where people are interested in the English literature. So it’s probably an answer to what you were saying, that mono-culture is dangerous because it tends to ignore the other countries, it tends to be … reduce you then to be closed on itself, and to have no openness on the outside world.

No, I mean it’s … In a way you can understand why the situation has a reason, because the production of books in the United States and in England is so huge. There are hundreds of thousands of books coming out every year, and somehow this market becomes self-sufficient, it doesn’t feel it needs an input from other parts of the world. And I think that only a couple of percent, in fact, are translated books, if you look at literature. And they are often badly translated, I would say. And they are published in small numbers. Whereas if you look at France, for instance, France is not quite as dominated by translations as Sweden is, but still it’s not far from 50% of the books in France and in Germany and in Russia. And, as you said, in Korea, and in Japan, and I think Chinese is moving up, actually, all say. So you have these, can we say, these old cultures … because all these countries are very old, they have a long standing literal tradition. They also have this tradition of translation, and of putting a high value in translation. You know that if we go back, and I think that goes for France as well, as for Sweden, to the eighteenth century, it was almost as prestigious to make o good translation, especially of a classical work, as to write an original work. And this high evaluation of translation has continued, well into our own days. And therefore, if I read for instance French translations of Swedish writers today, they are usually vastly superior to English translations, if there are any. And we can say the same thing for German translations and Russian translations. So we have this commerce of languages that is getting on, but that happens sort of outside the dominant culture, because we can’t look away from the fact that the Anglo-Saxon culture is dominant, in the way that it has designed the systems with which all the other countries communicate. The internet, television production and so on. And science is to a large extent Anglophile. And I think this is interesting. This makes for a lot of misunderstanding, I think. And a lot of bad feeling, too, as I have experienced, personally. Quite often when the Swedish Academy announces the name of the Nobel Prize winner, we are met with a complete lack of understanding from the English countries, because they have never heard of the man. There are few translations around, and they don’t quite get what it’s all about. I think that was partly true about your prize, for instance, and there are a lots of more good translations in other languages than English.

As I understand your relationship to French culture, to your own language, to your own literature, is not the typical one that you find with a French writer. I mean, I’ve been reading a lot of French writers and even if they often deny this fact quite often it’s so obvious that the very centre of their work is Paris, that’s where everybody wants to go, that’s where everybody wants to make a name, and there are certain rules and there are certain circles that you have to make yourself known by and you have to triumph on a certain scene. And this has been going on in very much the same way for hundreds of years, but somehow you don’t seem to belong to this play, this race, you have to a large extent even ignored it, I should say, could you comment on that? Why did you never quite go to Paris?

… I was raised with the belief that I was in France. I was there but I was not from there …

… I was raised with the belief that I was in France. I was there but I was not from there …Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: It’s a long story, I was born in the south of France, but my family was, as I mentioned, from Mauritius, so I was raised with the belief that I was in France. I was there but I was not from there, that I was from some other place. And when I was a child I tried to explain to my fellow students where I came from and they were not interested in the least bit, they were not interested at all in the Mauritian part of myself, and they even ignored that because at that time it was not so fashionable to be from Mauritius. So they ignored where it was and they thought it was St Maurice, a kind of suburb of Nice, but they could not understand why I was behaving in such a different way.

My father also tried to give us the … not an English education, but to value the English literature as well as the French literature, so he gave us a lot of English books to read and I must say I’ve read Gulliver’s Travels in the original, not in translation, and some ways my culture was really different from the others. So I did not feel so much attracted by the umbilical literature by the, you know, by the secret of the secrets by Paris, I didn’t feel so much attracted by that, I felt that being in Nice I was in, belonged more to the Mediterranean Sea than to the grey skies of Paris. And having Mauritian ancestors and Mauritian family I was more attracted by this kind of other world which was not exotic for me, it was the normal world, and I was using some Creole worlds in French which were not understood by the others, and my references were not in Paris at all. And in fact when I began to read the modern literature I was reading more American novels than French novels, I discovered very late the new “nouveax roman” and those writers, and to them I preferred the, I would say, the Jewish writers from New York, I felt they were much more inventive in the way they wrote stories like /- – -/ or Salinger, Salinger especially was very attractive for me.

Yes, you mentioned him.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Though he was describing a life I didn’t know really, it was the décor he was describing, I didn’t know anything about it, but I preferred the way he was telling the story, he was …

You said that Catcher in the Rye was an important book to you.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes, Catcher in the Rye because it was such an overwhelming way of telling a story. You had to be inside the body of a 14 year old and you were already 19 or 20, so already very far from that, and this man succeeded in making you feel you were in the body of a 14 year old, it was amazing, and no new novel in France was able to offer such a travel, such an experiment, and the humour, the good humour in the English literature was …I felt very attracted to that, and I felt like French literature was lacking cruelly this sense of humour, this distance. Very few writers had managed it and most writers in France were very serious, for me too serious.

So for all these reasons I didn’t feel very much interested by the Paris intelligentsia and the small chapels which were still alive when I was 20 years old. At first I refused to go to Paris and my publisher was asking for a picture so I went to an automatic picture and I sent him 4 ugly pictures and said I live in Nice, my father is English, my mother is French, that was all the details for us I was sending at the time, and they were asking me to come to Paris, and I was trying to invent a pretext not to go there. I think in a way I was afraid of Paris, I was afraid of getting to a foreign country, you know, to a place where I would not speak the language, a place where everything would be very intelligent and very serious and I had to give proofs of my seriousness which I was unable to do.

But your first book Le procès-verbal came out in 1963 was very well received I understand?

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes it was, yes it was, but in fact it was better received by Europe I would say because I was, when I was 22 years old the manuscript was offered for a prize which doesn’t exist anymore which was called the Formentor Prize and this prize was awarded by publishers from all Europe, so all the publishers had to translate this book and then to publish it in their … and they would publish it, and unfortunately, or maybe fortunately, I didn’t have this award, I didn’t get the Formentor Prize. The prize though was very interesting, it was a stay in the Island of Formentora for 15 days. The hotel was paid and the travel was paid and it was, for me, a terrific prize.

But I didn’t get it, it was Uwe Johnson, a German writer, who got that prize, but still as my book had been translated in all those languages, in German, French, Italian, not French, in Germany, this is a lapsus, in German, English, Italian, Spanish and some other languages, Portuguese, then it was ready to be known in Europe, so at once I got a European public and this was a great chance for me because I didn’t have to go through the triumph arc of the French Quartier Latin, I didn’t have to pay my respects to the critics in Paris, I was already known in Europe. That was a good thing, that was luck.

Still, I mean reading a book, if we move a bit ahead now in the list of your books, we come to a remarkable thing like L’extase matérielle. I find it very hard to imagine that book written in any other language but the French, this mixture of very good prose and “discours” which seems to be so very French, can you give us an idea of how you decide such a book, what made you write it in this way?

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: It’s a funny thing, because in fact it was not meant to be a book, at first it was meant to be a play, a theatre play, and it was the time where the Cinéma vérité, I don’t know the name of this in English Cinéma vérité, I need a name…

Describe what it is?

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: It’s a time where there were all those experiments with cinema, improvisation and there would not be any script. There was a writer who did that, Paul Bowles, he wrote a book which was the result of a discussion with a young Berber boy and this was recorded on a tape recorder and published as the raw material. This was very fashionable at that time, and with a friend of mine in Nice we were gathering in a small room and with the tape recorder and we were speaking and this would normally be a play, but in fact it would have been a terribly boring play because the subjects were very abstract, sometimes very philosophical or pretended to be very philosophical, and in other places they were kind of aggressive also, say political background. So eventually we renounced to do that play, but instead of go into the recorded material then I was trying to remember what we had talked about and I wrote it down, evening after evening, and it came out to be that book which was a mixture as you said of all this, some philosophy, some imagination, some poetry, some …

Some Rimbaud, some /- – -/ …

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes. Some mimicry also, I would say.

Some phenomenology perhaps even?

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes, yes.

And a bit …

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes.

That’s, you know, if you try to locate a philosophical standing point in the book I should say It’s probably phenomenological in the sense that you have this French tradition from the 1930’s, that’s Sartre, for instance.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes, we had also Lautréamont …

Yes absolutely.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: …who also was in a very daring way, wrote a book called Poetry which was not poetry at all, it was this kind of reflections and thinkings and probably provocative statements, so it’s a mixture of all this, very, very French, though Lautréamont was from Uruguay and myself were from a Mauritian family.

Well, you both had a domicile in the French literature traditions.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: We suffered both, this is a very common point, Lautréamont and myself, we suffered a lot in the grammar school, I mean in the “lycée”. It was a terrible time.

But I think it’s a natural starting point for a French writer is to suffer at school. isn’t it?

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes, yes.

I mean you have lots of writers with that experience.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Sartre did suffer as a student and then he suffered as a teacher, he suffered twice.

But you learn a lot in suffering.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes, yes. Yes it’s a good school of life. I was also teaching in England when I was 20 years old, I was teaching in a grammar school in Bath, very close to Bristol and it was amazing because it was a very harsh school with physical punishments and all the caricature of the English education, but still very …

A little bit of Dickens there, I suppose.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes, yes. Though it was a high class it was not a popular school.

Yes, I understand.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: It was a kind of private school.

Well then, if we move ahead a bit quickly now and come to something that to me looks like the sort of turning point in your career as a writer, the novel which is in French it’s called Désert, Desert, which came out in 1980 and was a big success and seems to have been the first book to give you a wide readership, not only in France but in many other countries. It was also, I think, celebrated by the French Academy which is something very unexpected in your case, you got a prize, I don’t remember the exact name of it but it’s a sort of novel prize that’s given by the French Academy. How did you come to write that book which is so different from your early books?

… at that time, I went to live in the forest with some American Indians …

… at that time, I went to live in the forest with some American Indians …Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: I think I reached at that time a crisis because I had been writing on myself, and to the point I felt disgusted by writing, and I, at that time, I went to live in the forest with some American Indians in the East of Panama in the Darien forests. I spent around three years there without writing, just living, moving and watching people and talking to them, and being pretty useless for the people themselves, but I came to understand all my errors there, it was a kind of psychoanalysis without any psychiatrists, I had to do that myself.

A sort of pilgrimage almost.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Not really, I was not prepared to what was happening there, I was not expecting anything, I was just attracted by the extraordinary beauty of the place and of the people, they were extremely beautiful people, and some of them, not all of them, but some of them were for me really like, I would say like teachers or like mentors. They helped me a lot to change my mind, so when I came out of there I got married, which was a change, and then I decided to speak about other people, not about me, this was really the change, I had to shift from myself to the others and from there, some of the critics were very indignant saying that I had …

You had betrayed yourself.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: … I had been a traitor, in fact I was a traitor to myself …

Yes, I remember that.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: But it’s a good thing to be a traitor to yourself when you can’t bear yourself any more, you have to survive, and literature can offer a good survival, it’s a …

In this book there is a violent clash between the north, an ancient north African culture that is based on the desert people, and the French culture or the culture of Europe, we can say the urbanised Europe. What were your sources in describing this traditional north African culture?

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: I wrote the first version of that book when I was 14 years old because at that time I really enjoyed writing adventure stories, so I wrote a first version of that novel which was called The White Sheik, I was inventing a Sheik who was resisting to the French in Morocco.

But that’s not altogether an invention, there was such a war of resistance in the early 20th century?

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes, so after that when I was married to Jemia, to my wife, I found out that she was the descendent of a leader in what was called the Rio de Oro or Western Sahara, the Spanish colony south of Morocco, and I read a lot about that man whose name was Ma al-Aynayn which means “the water from the eyes”, because he had watery eyes, he was afflicted by that, so this man was a leader, he was a Sufi philosopher and a leader, a very, very astonishing man who tried to resist both Spaniards and French and tried to expel the imperialist forces from the land.

That was before the first world war I think.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: That was the … it began in 1902 and it lasted until around 1911, 1912, and he died without seeing the victory. He was defeated by the French army which was overrunned, he was with his army, he was fighting with one very simple guns against the machine guns and especially the German machine guns which were sold to the French army at the time, so it was an unequal fight and he was defeated, but I was really attracted by this resistance spirit and it was very convenient for me because it gave me the impression that literature could be used for describing something else than just exotism or personal problems, that it could deal also with a movement.

It doesn’t at all give the effect of exotism when you read it because … Especially in the beginning of the book when you’re following this march through the desert, and these rites that take place in order to strengthen the spirit of resistance in this group of men, women and children which we are witnessing. It’s my impression that you approach a sort of sacred language, it’s the language of religious ceremony really, you come very close to that. I won’t call you a religious writer just because of that, but you have a sort of … there is a power, an attraction in it that very much resembles …

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: I was attracted by this figure because he was indeed not only a political leader, he was also a religious leader which meant at that time a good knowledge not only of religion but also in mathematics, in astronomy, the Sufi philosophers were well acquainted with sciences as well. He had a huge library, his personal library, which was probably a moving library because he had to change places, and which probably was dispersed, was liquidated after his defeat, and this kind of figure was, for me, a good example of what human beings can be, what sort of models they can be, because he was characterised by the French politics at that time as a fanatic, but he was not a fanatic. He was a very peaceful man, a very religious, peaceful, in some ways very modern, very tolerant, nothing to do with the present times, fundamentalism or fanatism, he was a good example of what was /- – -/ by the French forces and might have been different solution to the after colonialism, he would be, he would have been, definitely.

And then you, when you move on in the book, and you arrive at our own time and you have this main character Lalla who is a young girl whose ancestors were among the followers of this /- – -/, though she doesn’t know that, she just feels it somehow, and she goes across the Mediterranean and she comes to Marseilles I suppose … then the language of the book changes altogether it’s a new style, it’s a new approach, there’s a new way of writing that goes with this discovery of the urban world, of Europe, which is really like the kingdom of death, it’s like entering a world where no-one is really alive, that’s my impression in reading the book. This topic, image of our country, how did you come to that?

… it’s the kind of noble heritage they have, and you simply ignore it …

… it’s the kind of noble heritage they have, and you simply ignore it …Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes, well in fact you know when, what I really wanted to say or what was my main preoccupation is that when you travel in Europe you very often come, you very often meet very ordinary people, and those people can be workers in the street, they can be people plastering houses or repairing roofs, they could be people serving in the restaurants, and you don’t know their stories. But some of them belong to very ancient families, they have this kind of noble background which has nothing to do with being born noble but it’s the kind of noble heritage they have, and you simply ignore it, and those people are living in terrible situations.

They are renting poor rooms in very bad parts of the city, they are confronted to violence every day and they see the worst part of our modern civilisation, and it’s surely very difficult to compare what they see to what they are, they are refined and they have a very elegant and very significant family background. And when they are in Europe they are isolated and sometimes they are compelled to live with criminals or with the destructive parts of the population, sometimes they are even by chance taken and put into jail and they don’t understand that. So it’s this contradiction between what they are and what they look like, what they seem to us and what they are really in their soul.

And I suppose that’s in a way an allegory of global relationships because …

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes it is, it is.

… across distances we tend to look at some foreign people in that way.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: I was stricken by a sight when I was going to England, it was around the late 50’s, I used to go very often to England, I was a student at the university of Bristol, so I was taking the boat because at that time you were not taking the plane. And when I was taking the boat on the same boat going between Calais and Dover, on the main deck of the boat you were seeing a population coming from Africa, and some of these people had travelled for months before reaching that boat, they were trying to get into England to find jobs in England. It was the beginning of what was called after that the general immigration, at that time we were not speaking of immigrants, we were just speaking of workers, and those people, some of those people, they looked so dignified, they were coming to England dressed in their robes, African robes, with the hat made of leopard skin, and they did not speak a word of English.

They had on their face the scars from their tribes in Africa and they looked, and they looked so afraid on the deck of the boat, and once I tried to speak to some of them and I tried to speak in English, in pigeon English, and for some reason they did not understand. They looked so frightened and I was asking to myself why are those people who look like kings, why are they so frightened to come to Europe? And after that I got the answer that most of the people thought that they had to go because of economical reasons. Bbut they knew, or they were persuaded that most of them would die there, they were going to their deaths, and they were convinced that England was a place where they would be killed, but they had to go there to escape hunger and economical difficulties in Nigeria or Uganda. But they still were convinced that maybe they would die there, this is amazing, because generally the Europeans think about themselves as living in a very safe place and for Africans it was a terribly dangerous place to go to.

Maybe in some ways it was also.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Maybe in some ways it was. So this, probably those situations gave me the need to write, to try to change my personal thing to …

You see this French city from the inside on this immigrant that actually it’s completely foreign to everything she sees.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: The same thing was happening in France for the people coming from North Africa, the general opinion for the French people was that most of them are criminals, most of these people coming from north Africa are criminals, and for the north Africans they were getting into a country of criminals, so it was …

Complete misunderstanding from both sides.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: From both sides.

I have to ask you before we get to the close a little about your latest book because it’s apparent that if we move onto the books you’ve written in this century, you have begun to exploit the history of your own family in a way that you didn’t do before. Of course this started in the 90’s with books like Onitsha who is partly a story about your experience of Africa and your father’s experience of Africa but not quite, and a book like La Quarantaine also has a lot of material that has to do with Mauritius and your family background, and this wonderful story of, was it your grandfather Jacques, who saw Rimbaud coming out of the bistro at the corner of Rue Madame in Saint-Sulpice – that becomes a sort of legend that you have to follow on, but as you read these books, Révolutions, for instance, or L’Africain and now Ritournelle de la faim you realise that you’re not quite telling the real story, those are not facts, this is still a novel. It’s sometimes called a semi-autobiographical but that’s a rather elusive term I think. Which is the relationship actually in those books between fiction and actuality?

… I was overwhelmed by this need to explain who I was …

… I was overwhelmed by this need to explain who I was …Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: The first books I was writing were closer to autobiography because I was, as I told, speaking about myself and I was overwhelmed by this need to explain who I was and what were my reactions to the modern world, to the city, to the violence of the city. And when I decided to change and to speak about the others naturally the subjects would be the closest person I would know, and those closest persons were from my family, but I didn’t use my family really, I was not trying to give a detailed relation of what my family had been, what they had experimented, I was more interested by the kind of, not symbol, but a kind of exemplary history they had been through. One of my grandfathers was a judge in Mauritius, was sent to a very isolated island, /- – -/ and didn’t enjoy so much life there, so he invented the story of this treasure and I found this was a good idea to replace a boring reality by something which would give an aim to his life, and he was really a prisoner of this dream and was trying to reach, to find the treasure which in my mind didn’t exist, was just an invention …

So you transform that in your book to another kind of treasure?

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: I thought it was a good theme for a novel, trying to find something which doesn’t exist, it generally could be a resumé of most novels, most heroes or anti-heroes start trying to find something which doesn’t exist.

But your hero finds something else.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes of course, because you always find something else, and I suppose my grandfather also found something else which was the love of the Rodriguan people, he was … then he went to Rodriguez Island and got in so good relations with the people, I happened to meet a very old man who knew my grandfather and accompanied my grandfather when he was doing his research for this treasure and this man told me in Creole that my grandfather was … as soon as he was getting to Rodriguez he would take off his jacket, his celluloid collar and be in sleeves, and then would sing all the time. I can’t imagine my grandfather singing, he was a judge after all, can you imagine a judge singing? And then some other people in my family had other experiences which were formly symbolic of those times, and Ritounelle de la faim, the ultimate novel I published I was…

You make your mother slightly younger I think in…

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes, much younger, 10 years younger, because my idea was what is it to live a war when you are 20 years old, when you are ready to live and you’re ready to be happy, to marry and to lead a peaceful and a life full of love. And then war comes and you are separated from your love and everything is crumbling everywhere, your family is falling down and they are losing their money, they are losing their properties and so this was the idea, because I feel that nowadays we are in some places of the world people are living this, exactly this, we are not aware of it but in some places …

Yes certainly.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: … women are separated from their love and I was, I wanted also to speak about the people who are not heroes in wars, because I hardly can think that a general is a hero, I think the real heroes are the survivors, the civilians who survive wars, the women who find food and try to escape from bombings and try to survive with their children. Very, very marvellous writer in Korea, Hwang Sok-yong, who wrote a book called Monsieur Han, Mr Han, … and he tells about his crossing of a river escaping from North Korea to South Korea in the middle of bombs, and he described the same situation, so this type of situation happens again and again and is still happening now.

Well, shall we stop here?

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes.

I’m most satisfied and I hope you are too.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Yes. It was a very pleasant moment, I could have …

Thank you very much.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: … could have lasted longer.

Yes. Thank you.

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio: Thank you.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Interview with the 2008 Nobel Laureate in Literature, Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio, 6 December 2008. The interviewer is Horace Engdahl, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy.

The 2008 Literature Laureate discusses the importance of languages in his career and the literary world, his non-traditional relationship with the French culture and language (12:03), the crisis that led to a turning point in his writing career (25:25), and why he began to explore his own family history in recent books (41:08).

Nobel Prizes and laureates

See them all presented here.