Shimon Peres

Nobel Lecture

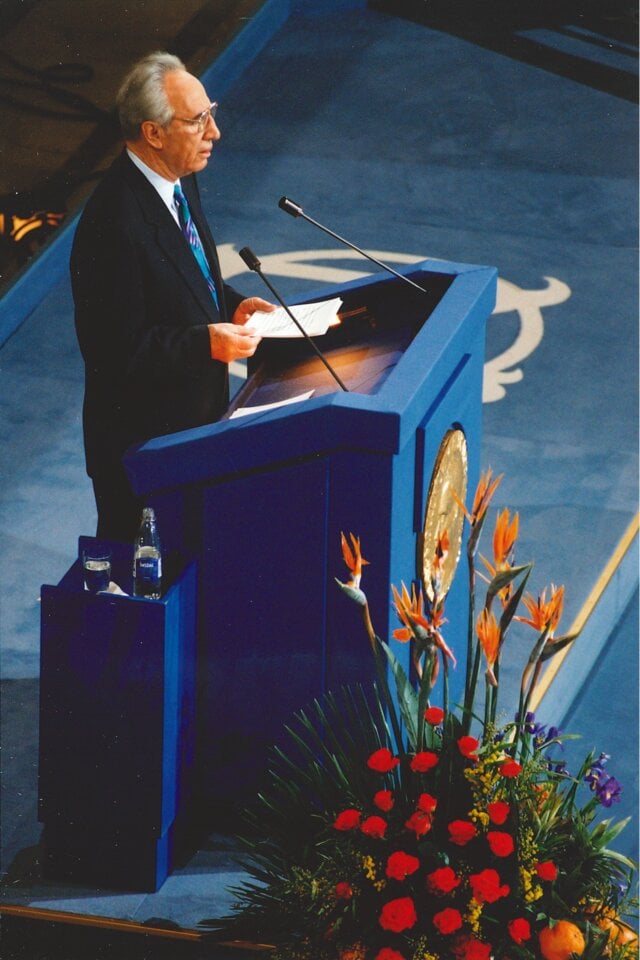

Shimon Peres delivering his Nobel Prize lecture.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

Your Majesties,

Members of the Nobel Committee,

Prime Minister Brundtland,

Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin,

Chairman Arafat,

Members of the Norwegian Government,

Distinguished Guests,

I thank the Nobel Prize Committee for its decision to name me among the laureates of the Peace Prize this year.

I am pleased to be receiving this Prize together with Yitzhak Rabin, with whom I have labored for long years for the defence of our country and with whom I now labor together in the cause of peace in our region.

I believe it is fitting that the Prize has been awarded to Yasser Arafat. His abandonment of the path of confrontation in favor of the path of dialogue, has opened the way to peace between ourselves and the Palestinian people.

We are leaving behind us the era of belligerency and are striding together toward peace. It all began here in Oslo under the wise auspices and goodwill of the Norwegian people.

From my earliest youth, I have known that while one is obliged to plan with care the stages of one’s journey, one is entitled to dream, and keep dreaming, of its destination. A man may feel as old as his years, yet as young as his dreams. The laws of biology do not apply to sanguine aspiration.

I was born in a small Jewish town in White Russia. Nothing Jewish now remains of it. From my youngest childhood I related to my place of birth as a mere way station. My family’s dream, and my own, was to live in Israel, and our eventual voyage to the port of Jaffa was like making a dream come true. Had it not been for this dream and this voyage, I would probably have perished in the flames, as did so many of my people, among them most of my own family.

I went to school at an agricultural youth village in the heart of Israel. The village and its fields were enclosed by barbed wire which separated their greenness from the bleakness of the enmity all around. In the morning, we would go out to the fields with scythes on our backs to harvest the crop. In the evening, we went out with rifles on our shoulders to defend our village. On Sabbaths we would go out to visit our Arab neighbors. On Sabbaths, we would talk with them of peace, though the rest of the week we traded rifle fire across the darkness.

From the Ben Shemen youth village, my comrades and I went to Kibbutz Alumot in the Lower Galilee. We had no houses, no electricity, no running water. But we had magnificent views and a lofty dream: to build a new, egalitarian society that would ennoble each of its members.

Not all of it came true, but not all of it went to waste. The part that came true created a new landscape. The part that did not come true resides in our hearts.

For two decades, at the Ministry of Defence, I was privileged to work closely with a man who was and remains, to my mind, the greatest Jew of our time. From him I learned that the vision of the future should shape the agenda for the present; that one can overcome obstacles by dint of faith; that one may feel disappointment – but never despair. And above all, I learned that the wisest consideration is the moral one. David Ben-Gurion has passed away, yet his vision continues to flourish: to be a singular people, to live at peace with our neighbors.

The wars we fought were forced upon us. Thanks to the Israel Defence Forces, we won them all, but we did not win the greatest victory that we aspired to: release from the need to win victories.

We proved that the aggressors do not necessarily emerge as the victors, but we learned that the victors do not necessarily win peace.

It is no wonder that war, as a means of conducting human affairs, is in its death throes and that the time has come to bury it.

The sword, as the Bible teaches us, consumes flesh but it cannot provide sustenance. It is not rifles but people who triumph, and the conclusion from all the wars is that we need better people, not better rifles – to win wars, and mainly to avoid them.

There was a time when war was fought for lack of choice. Today it is peace that is the “no-choice” option. The reasons of this are profound and incontrovertible. The sources of material wealth and political power have changed. No longer are they determined by the size of territory obtained by war. Today they are a consequence of intellectual potential, obtained principally by education.

Israel, essentially a desert country, has achieved remarkable agricultural yields by applying science to its fields, without expanding its territory or its water resources.

Science must be learned; it cannot be conquered. An army that can occupy knowledge has yet to be built. And that is why armies of occupation are a thing of the past. Indeed, even for defensive purposes, a country cannot rely on its army alone. Territorial frontiers are no obstacle to ballistic missiles, and no weapon can shield from a nuclear device. Today, therefore the battle for survival must be based on political wisdom and moral vision no less than on military might.

Science, technology, and information are – for better or worse – universal. They are universally available. Their availability is not contingent on the color of skin or the place of birth. Past distinctions between West and East, North and South, have lost their importance in the face of a new distinction: between those who move ahead in pace with the new opportunities and those who lag behind.

Countries used to divide the world into their friends and foes. No longer. The foes now are universal – poverty, famine, religious radicalization, desertification, drugs, profileration of nuclear weapons, ecological devastation. They threaten all nations, just as science and information are the potential friends of all nations.

Classical diplomacy and strategy were aimed at identifying enemies and confronting them. Now they have to identify dangers, global or local, and tackle them before they become disasters.

As we part a world of enemies, we enter a world of dangers. And if future wars break out, they will probably be wars of protest, of the weak against the strong, and not wars of occupation, of the strong against the weak.

The Middle East must never lose pride in having been the cradle of civilization. But though living in the cradle, we cannot remain infants forever.

Today as in my youth, I carry dreams. I would mention two: the future of the Jewish people and the future of the Middle East.

In history, Judaism has been far more successful than the Jews themselves. The Jewish people remained small but the spirit of Jerusalem went from strength to strength. The Bible is to be found in hundreds of millions of homes. The moral majesty of the Book of Books has been undefeated by the vicissitudes of history.

Moreover, time and again, history has succumbed to the Bible’s immortal ideas. The message that the one, invisible God created Man in His image, and hence there are no higher and lower orders of man, has fused with the realization that morality is the highest form of wisdom and, perhaps, of beauty and courage too.

Slings, arrows and gas chambers can annihilate man, but cannot destroy human values, dignity, and freedom.

Jewish history presents an encouraging lesson for mankind. For nearly four thousand years, a small nation carried a great message. Initially, the nation dwelt in its own land; later, it wandered in exile. This small nation swam against the tide and was repeatedly persecuted, banished, and down-trodden. There is no other example in all of history, neither among the great empires nor among their colonies and dependencies – of a nation, after so long a saga of tragedy and misfortune, rising up again, shaking itself free, gathering together its dispersed remnants, and setting out anew on its national adventure. Defeating doubters within and enemies without. Reviving its land and its language. Rebuilding its identity, and reaching toward new heights of distinction and excellence.

The message of the Jewish people to mankind is that faith and moral vision can triumph over all adversity.

The conflicts shaping up as our century nears its close will be over the content of civilizations, not over territory. Jewish culture has lived over many centuries; now it has taken root again on its own soil. For the first time in our history, some five million people speak Hebrew as their native language. That is both a lot and a little: a lot, because there have never been so many Hebrew speakers; but a little, because a culture based on five million people can hardly withstand the pervasive, corrosive effect of the global television culture.

In the five decades of Israel’s existence, our efforts have focused on reestablishing our territorial center. In the future, we shall have to devote our main effort to strengthen our spiritual center. Judaism – or Jewishness – is a fusion of belief, history, land, and language. Being Jewish means belonging to a people that is both unique and universal. My greatest hope is that our children, like our forefathers, will not make do with the transient and the sham, but will continue to plow the historical Jewish furrow in the field of the human spirit; that Israel will become the center of our heritage, not merely a homeland for our people; that the Jewish people will be inspired by others but at the same be to them a source of inspiration.

In the Middle East most adults are impoverished and wretched. A new scale of priorities is needed, with weapons on the bottom rung and a regional market economy at the top. Most inhabitants of the region – more than sixty percent – are under the age of eighteen. A new future can be offered to them. Israel has computerized its education and has achieved excellent results. Education can be computerized throughout the Middle East, allowing young people to progress not just from grade to grade, but from generation to generation.

Israel’s role in the Middle East should be to contribute to a great, sustained regional revival. A Middle East without wars, without enemies, without ballistic missiles, without nuclear warheads.

A Middle East in which men, goods and services can move freely without the need for customs clearance and police licenses.

A Middle East in which every believer will be free to pray in his own language – Arabic, Hebrew, Latin, or whatever language he chooses – and in which the prayers will reach their destination without censorship, without interference, and without offending anyone.

A Middle East in which nations strive for economic equality and encourage cultural pluralism.

A Middle East where every young woman and man can attain university education.

A Middle East where living standards are in no way inferior to those in the world’s most advanced countries.

A Middle East where waters flow to slake thirst, to make crops grow and deserts bloom, in which no hostile borders bring death, hunger, and despair.

A Middle East of competition, not of domination. A Middle East in which men are each other’s hosts, not hostages.

A Middle East that is not a killing field but a field of creativity and growth.

A Middle East that honors its history so deeply that it strives to add to it new noble chapters.

A Middle East which will serve as a spiritual and cultural focal point for the entire world.

While thanking for the Prize, I remain committed to the process. We have reached the age where dialogue is the only option for our world.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

See them all presented here.