Explore the contributions, careers and lives of 19 women who have been awarded Nobel Prizes for their scientific achievements.

Photo: Johns Hopkins Medicine

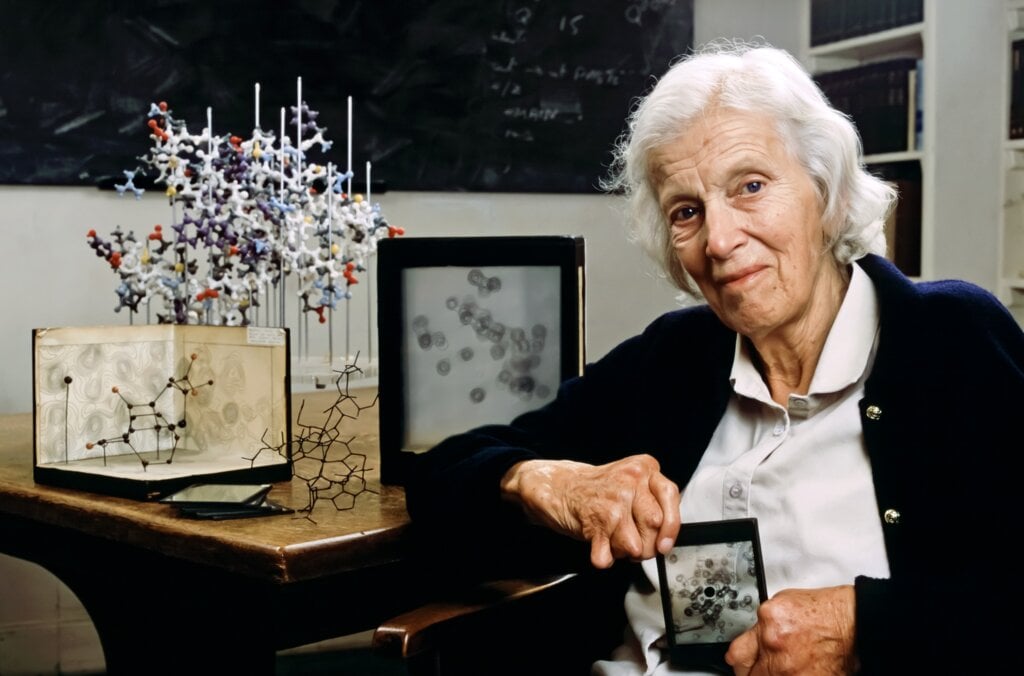

“Captured for life by chemistry and by crystals,” as she described it, Dorothy Hodgkin turned a childhood interest in crystals into the ground-breaking use of X-ray crystallography to “see” the molecules of penicillin, vitamin B12 and insulin. Her work not only allowed researchers to better understand and manufacture life-saving substances, it also made crystallography an indispensable scientific tool.

Born Dorothy Mary Crowfoot in 1910, Hodgkin was raised in England and colonial North Africa. As a child, she was fascinated with crystals; she loved the elegance of their geometric shapes. At age 14, she found a shiny black mineral in the yard while visiting her parents in North Africa, and she asked a family friend, soil scientist A. F. Joseph, if she could analyse it. Joseph gave her a surveyor’s box of reagents and minerals to encourage her.

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin with her mother and sisters.

Photo: Courtesy of the Hodgkin family

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin in her late teens (in the 1920s).

Photo: Courtesy of the Hodgkin family

At age 16, she received another present, one that would set her on her life’s path: a book by William Henry Bragg about using X-rays to analyse crystals.

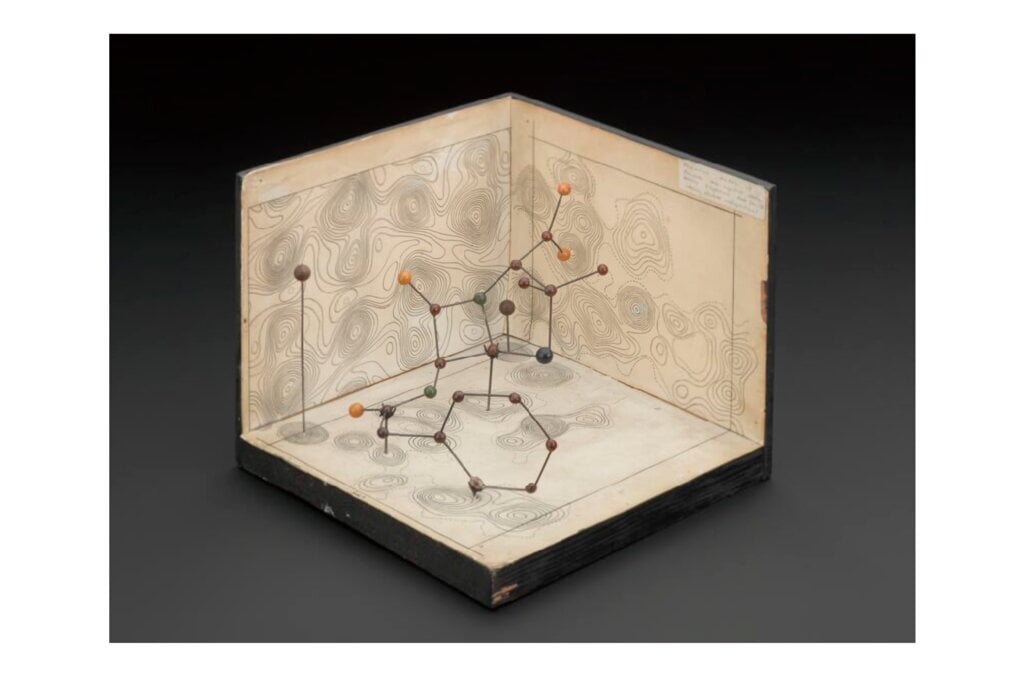

X-ray crystallography allowed scientists to see the structure of molecules that had until then been visualised only in theory. The process involves beaming X-rays through a crystal onto a photographic plate, which records the scatter pattern caused by the interference of electrons surrounding the atoms. That process is repeated with a variety of selected orientations. Then a series of mathematical calculations is used to relate the spots on the plates to the relative arrangement of the atoms.

When she was 18, Hodgkin enrolled at Oxford University to study chemistry and pursue her interest in crystallography. For her doctoral work, she joined the lab of J. D. Bernal, a Cambridge University chemist who believed in equal opportunity for women. He helped make crystallography one of the few physical sciences hiring significant numbers of women at that time. In 1934, Bernal photographed the first X-ray of a protein crystal, an achievement that proved organic molecules (and not just inorganic ones) could be crystallised.

Hodgkin wasn’t in the laboratory on the day of this breakthrough; she was at the doctor because of pain in her hands. Although she was diagnosed with chronic rheumatoid arthritis, she quickly returned to work. She never let the disease stop her, though her hands and feet grew increasingly swollen, twisted and painful.

Inspired by the first X-ray of a protein crystal, Hodgkin soon began to investigate the three-dimensional structure of insulin. At this point, she was 24 and teaching chemistry back at Oxford University, with her own (albeit poorly equipped) lab.

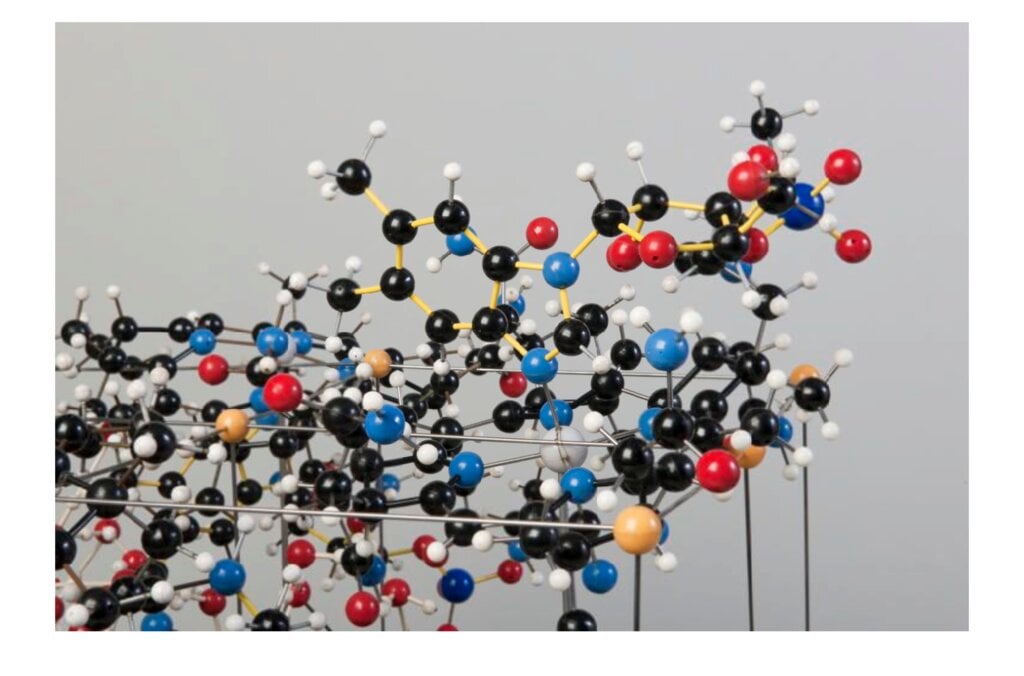

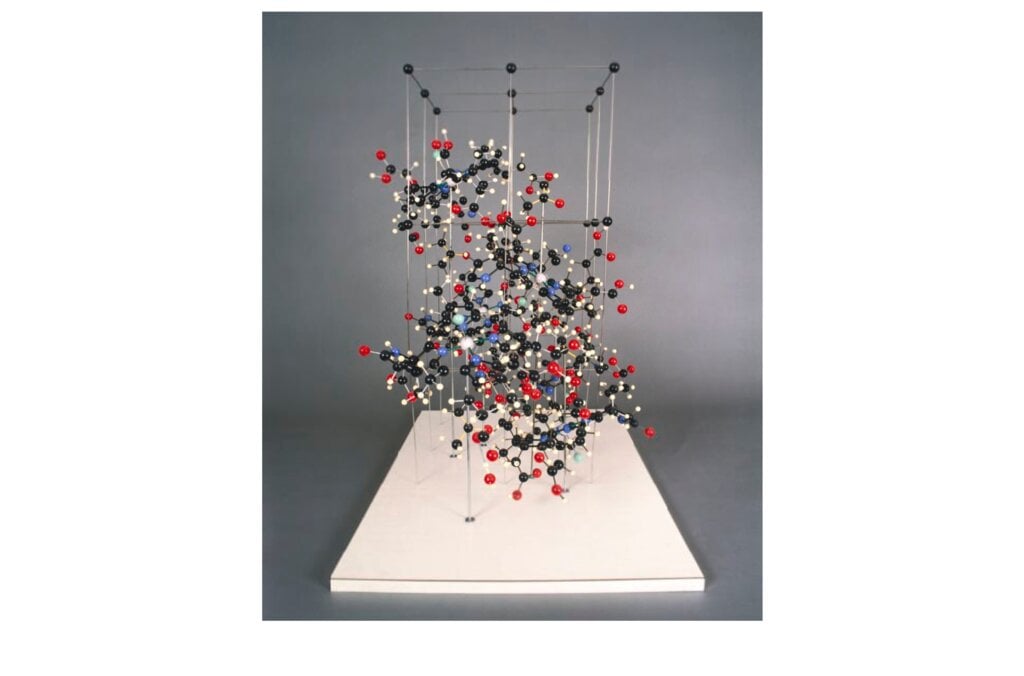

She paused in her study of insulin to take on penicillin, a more urgent task in the World War II era; it took her four years to map the structure of its 17 atoms. Vitamin B12, which she tackled next, contains 181 atoms and took eight years to map. Eventually she conquered insulin; with 788 atoms, it took 34 years.

“I believe in perfecting the world and trying to do everything to improve things, but not because I know what’s to come of it.”

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

The almost insurmountable size of these tasks and the sheer volume of calculations they required turned Hodgkin into an early adopter of evolving technology.

Hodgkin believed in international scientific cooperation. During the Cold War, she insisted on including Chinese and Soviet scientists in organisations such as the International Union of Crystallography, which she helped found.

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin with chemist and peace activist Linus Pauling, 1957.

Photo from the Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Papers, Oregon State University Special Collections & Archives Research Center

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin (second from left) with Ivan Zupec and Linus and Ava Helen Pauling, 1977.

Photo from the Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Papers, Oregon State University Special Collections & Archives Research Center

She was also a lifelong advocate for world peace, her conviction formed in part by her mother’s loss of all four brothers in World War I. She campaigned against both the Vietnam War and nuclear weapons.

A letter from chemist and peace activist Linus Pauling recommending Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin for the Lenin Peace Prize, 7 January 1983.

Photo from the Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Papers, Oregon State University Special Collections & Archives Research Center

Page two of the letter.

“How to abolish arms and achieve a peaceful world is necessarily our first objective,” she wrote in 1981. At that time, at age 71, she was president of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, established to address the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

Hodgkin’s life work had immediate implications for medical research. Mapping the structure of penicillin in 1945 made the miracle drug far easier to manufacture. Vitamin B12, which Hodgkin mapped in 1954, is an essential weapon against pernicious anaemia. Her detailed map of insulin in 1969 allowed for vast improvements in the treatment of diabetes. But her achievements resonated beyond their practical applications, expanding limits of X-ray crystallography and thus of scientific knowledge.

Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1964

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 344 kB

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm, December 10, 1964

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen,

I must first of all with all my heart thank you for the very great honour that you have done me and the great happiness that you have conferred upon me and my family today. My breath is quite taken away by the succession of impressions, this beautiful city and this beautiful golden byzantine hall, the meeting with very many old friends, and the making of very many new ones, the coming of my children by adventurous journeys from different parts of the world, all of this makes it difficult for me to stop and be serious at all this evening.

I must admit that when I first saw the list of Nobel Laureates, sent to me for this occasion, and saw that it began with Roentgen and X-rays, and van ‘t Hoff, whom I connect with ‘chemistry in space’, – whom Your Majesty will remember having seen at the beginning – I found myself suddenly thinking how very appropriate that I should be here today. But now – of course – my heart a little fails me, thinking also of all of the great names between us, and of all those on whom my work has depended, whose encouragement has brought me here today, on whose hands and on whose brains I have relied. I could hardly stand here, were it not that I am supported by the pleasure and congratulations that have come to me from all over the world. And now I must tell you, that the last night that we were in England, we were being entertained at an Arabian party in London. My hosts advised me then, telling me how one should reply in Arabic to congratulations that one receives, congratulations on some very happy event: the birth of a son, perhaps or the marriage of a daughter. And one should reply: “May this happen also to you.” And now even my imagination will hardly stretch so far that I can say this to every one in this great hall. But at least, I think, I might say to the members of the Swedish Academy of Science: “In so far as it has not happened to you already, may this happen also to you!”

At the banquet, S. Friberg, Rector of the Caroline Institute, made the following remarks: Mrs. Crowfoot Hodgkin, Mr. Bloch and Lynen. When one of you received the news by telephone, that you had been awarded the Nobel Prize, you modestly asked: “Why?” Each and all of you would have been fully justified in asking the same question by entirely different reasons, for you have all achieved such outstanding results, that several merit a Nobel award. I believe, that I may be permitted the indiscretion of revealing that the only problem relating to your prizes was to decide whether they should be awarded in medicine or chemistry. Your intellectual accomplishments and the immense technical difficulties, you had to overcome can only be grasped by the specialist, but their significance can be understood by all. Within the foreseeable future, your discoveries may provide us with weapons against some of mankind’s gravest maladies, above all in relation to cardiovascular diseases. Achievements like yours make it not unrealistic to look forward to a time, when mankind will not only live under vastly improved conditions, but will itself be better.

Mrs Crowfoot Hodgkin, Address to the University Students on the Evening of December 10, 1964

Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Students of Stockholm:

I am very happy indeed to hear you speak today as you do. We knew, when we came here as Laureates from our different countries, that we should greatly enjoy meeting one another and talking together about scientific problems in our international language. I do not think that any of us had realized how much more this festival might mean both to you in Sweden and to the whole world. I was chosen to reply to you this evening as the one woman of our group, a position, which I hope very much will not be so very uncommon in future that it will call for any comment or distinctions of this kind, as more and more women carry out research in the same way as men. But I might have been chosen for you for other reasons to reply to your speech, as a country woman of Tom Paine who wrote an early book of the rights of man, from whom the declaration of human rights which you mentioned today derives.

With great seriousness I thank you for your words and say that we share your anxieties and your endeavours. I see all of you here, the hope of the world, the hope of getting the kind of world that we all want and I should like to say – that knowing my own children – that I think that this hope is very soundly based in a solid and scientific sense. As you know I heard the news of my Nobel award in Ghana, in the newly independent country where we are very conscious of the need to work for peace and progress and we celebrated this Nobel Prize in my husband’s institute of African studies with an enormous party and with dances danced by the students of music and drama. There were some very traditional court dances at the ashanti, a hunter dance of the Ewe people, one quite modern dance, symbolizing work and happiness, and I made a speech there under the stars in Africa, saying that never before was a Nobel Prize celebrated in this way. But I think I was quite wrong, for it seems to me that here every year you celebrate Nobel Prizes in this way with singing and dancing in Stockholm, and here too you make this world here and now the kind of place that we all want to live in. Thank you very much.

On Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin from The Chemical Heritage Foundation

On Dorothy Hodgkin from PBS Online

On Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin from the Lindau Mediatheque

Dorothy Crowfoot-Hodgkin in Uppsala, Sweden, in 1964. Photo: Uppsala-Bild/Upplandsmuseet. CC BY NC ND 4.0.

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin Photo: University of Bristol, CC BY-SA 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Molecular model of penicillin by Dorothy Hodgkin, c.1945.

Photo: Science Museum London/Science and Society Picture Library [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Dorothy Crowfoot was born in Cairo on May 12th, 1910 where her father, John Winter Crowfoot, was working in the Egyptian Education Service. He moved soon afterwards to the Sudan, where he later became both Director of Education and of Antiquities; Dorothy visited the Sudan as a girl in 1923, and acquired a strong affection for the country. After his retirement from the Sudan in 1926, her father gave most of his time to archaeology, working for some years as Director of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and carrying out excavations on Mount Ophel, at Jerash, Bosra and Samaria.

Her mother, Grace Mary Crowfoot (born Hood) was actively involved in all her father’s work, and became an authority in her own right on early weaving techniques. She was also a very good botanist and drew in her spare time the illustrations to the official Flora of the Sudan. Dorothy Crowfoot spent one season between school and university with her parents, excavating at Jerash and drawing mosaic pavements, and she enjoyed the experience so much, that she seriously considered giving up chemistry for archaeology.

She became interested in chemistry and in crystals at about the age of 10, and this interest was encouraged by Dr. A.F. Joseph, a friend of her parents in the Sudan, who gave her chemicals and helped her during her stay there to analyse ilmenite. Most of her childhood she spent with her sisters at Geldeston in Norfolk, from where she went by day to the Sir John Leman School, Beccles, from 1921-28. One other girl, Norah Pusey, and Dorothy Crowfoot were allowed to join the boys doing chemistry at school, with Miss Deeley as their teacher; by the end of her school career, she had decided to study chemistry and possibly biochemistry at university.

She went to Oxford and Somerville College from 1928-32 and became devoted to Margery Fry, then Principal of the College. For a brief time during her first year, she combined archaeology and chemistry, analysing glass tesserae from Jerash with E.G.J. Hartley. She attended the special course in crystallography and decided, following strong advice from F.M. Brewer, who was then her tutor, to do research in X-ray crystallography. This she began for part II Chemistry, working with H.M. Powell, as his first research student on thallium dialkyl halides, after a brief summer visit to Professor Victor Goldschmidt’s laboratory in Heidelberg.

Her going to Cambridge from Oxford to work with J.D. Bernal followed from a chance meeting in a train between Dr. A.F. Joseph and Professor Lowry. Dorothy Crowfoot was very pleased with the idea; she had heard Bernal lecture on metals in Oxford and became, as a result, for a time, unexpectedly interested in metals; the fact that in 1932 he was turning towards sterols, settled her course.

She spent two happy years in Cambridge, making many friends and exploring with Bernal a variety of problems. She was financed by her aunt, Dorothy Hood, who had paid all her college bills, and by a £75 scholarship from Somerville. In 1933, Somerville, gave her a research fellowship, to be held for one year at Cambridge and the second at Oxford. She returned to Somerville and Oxford in 1934 and she has remained there, except for brief intervals, ever since. Most of her working life, she spent as Official Fellow and Tutor in Natural Science at Somerville, responsible mainly for teaching chemistry for the women’s colleges. She became a University lecturer and demonstrator in 1946, University Reader in X-ray Crystallography in 1956 and Wolfson Research Professor of the Royal Society in 1960. She worked at first in the Department of Mineralogy and Crystallography where H.L. Bowman was professor. In 1944 the department was divided and Dr. Crowfoot continued in the subdepartment of Chemical Crystallography, with H.M. Powell as Reader under Professor C.N. Hinshelwood.

When she returned to Oxford in 1934, she started to collect money for X-ray apparatus with the help of Sir Robert Robinson. Later she received much research assistance from the Rockefeller and Nuffield Foundations. She continued the research that was begun at Cambridge with Bernal on the sterols and on other biologically interesting molecules, including insulin, at first with one or two research students only. They were housed until 1958 in scattered rooms in the University museum. Their researches on penicillin began in 1942 during the war, and on vitamin B12 in 1948. Her research group grew slowly and has always been a somewhat casual organisation of students and visitors from various universities, working principally on the X-ray analysis of natural products.

Dorothy Hodgkin took part in the meetings in 1946 which led to the foundation of the International Union of Crystallography and she has visited for scientific purposes many countries, including China, the USA and the USSR. She was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1947, a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences in 1956, and of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (Boston) in 1958.

In 1937 she married Thomas Hodgkin, son of one historian and grandson of two others, whose main field of interest has been the history and politics of Africa and the Arab world, and who is at present Director of the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana, where part of her own working life is also spent. They have three children and three grandchildren. Their elder son is a mathematician, now teaching for a year at the University of Algiers, before taking up a permanent post at the new University of Warwick. Their daughter (like many of her ancestors) is an historian-teaching at girls’ secondary school in Zambia. Their younger son has spent a pre-University year in India before going to Newcastle to study Botany, and eventually Agriculture. So at the present moment they are a somewhat dispersed family.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin died on July 29, 1994.

High hopes for quantum technologies

Close up of A positive blood in bag.

Credit: ER Productions Limited/Getty Images

For curious learners

Explore the contributions, careers and lives of 19 women who have been awarded Nobel Prizes for their scientific achievements. Photo: Johns Hopkins Medicine

Women who changed science

Related content

The story behind insulin

Mapped the structure of insulin

More Nobel Prize-awarded work in medicine

The 2024 chemistry laureate believes that progress in science is made by working together and sharing ideas. Listen to him talk about how he sees mentoring as one of the most essential parts of his job. Hear the 2024 physics laureate talk about the development of AI, his fascination with understanding the human brain and how his family legacy of successful scientists put pressure on Hinton to follow in their footsteps. “Asking is hard. Once you realise there’s an interesting question to develop answers to, it is even harder.” Listen to the 2024 economic sciences laureate.

Listen to the podcast series Nobel Prize Conversations

Aage Bohr and Niels Bohr on the occasion of the defence of Aage's doctoral thesis, 1954.

Photo: Niels Bohr Archive, Copenhagen.