Transcript from an interview with the 2006 physics laureates

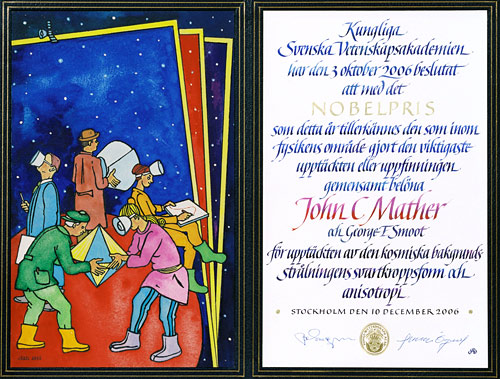

Interview with the 2006 Nobel Prize laureates in physics, John C. Mather and George F. Smoot on 6 December 2006. The interviewer is Adam Smith, Editor-in-Chief of Nobelprize.org.

John Mather, George Smoot, welcome to Stockholm.

John Mather: Thank you.

George Smoot: Thank you very much.

When you very kindly spoke to me just after you had heard the news that you had been awarded the prize, George Smoot, you mentioned that you had 170 students in California who were expecting you to be there this week.

George Smoot: That’s correct. My superior and chairman at the department is teaching my lecture later today and my alarm already went off saying so to my lecture but there’s now a time difference, so she still has three more hours.

So the students have been understanding, do you think?

George Smoot: Yes, though they were disrupted by photographers and other things that went on.

Teaching is a very important part of your research career?

George Smoot: I see my job as both doing research and preparing the next generation. I like teaching. This semester I am teaching freshman physics, the second semester of freshman physics, it’s the thermophysics and electromagnetism. It’s a hard course for the students, but it is for all those who are going to become scientists years later.

Is it unusual for somebody at your level to continue to teach undergraduates?

George Smoot: It may be unusual, but the university requires us to teach, so unless you can pull the strings to teach upper division or graduate courses all the time – which some people do – your … will easily go between lower division which is the first and second year and the upper and graduate courses. I go between those.

Is undergraduate teaching a big part of your life as well?

John Mather: No, since I am a full time NASA employee my job is primarily to conceive and build new space projects. I do a lot of public speaking now, especially now since the prize announcement, but my main job is working on the project. In my case now is the James Webb Space Telescope, which is the successor planned for the Hubble Space Telescope. It would go up in 2013, so that’s my main job.

Do you pull graduate students into …

John Mather: We can, but we don’t usually, because it is hard for a student to compete with the professionals and get a thesis project from working on something that is being built. Mostly the graduate students work with missions that have already been launched.

It would be interesting to explore the difference between choosing students, graduate students to work on projects, and professionals to work on NASA projects. What do you look for when you look for those people?

George Smoot: It’s very different because with professionals on a big project like John’s project or the space project we are doing, you have to meet a deadline, you are meeting other people who are well trained and experienced are there and everyone has to work together as a team and meet the deadlines. With the students you are bringing them on because they show promise, and they need to learn and experience how to do science. It is very good to get them involved part time in a big project so they can learn about that later, but you have a small project that they are responsible for. If they get in trouble, you’ll have to bail them out in the big project. If they get in trouble on their own project, you can let them flounder until they find their way and it is very different. Right now I have five graduate students, one, … from Korea; one Daniels from Mexico; there’s two Americans, Mia Emm and Michelle Delinski who are Americans, and then I have one Italian student, Sarah … They are all doing different things, Sarah is working on the next generation cosmic background satellite, but she is working on how to separate the foregrounds from nearby galaxies’ signals from the distant signals.

So, microcosm of the international space center really.

George Smoot: For me there is sort of a sequence, you’re not only working in projects that are going on, the way that John is really focusing on, major projects, the James Webb is one of the biggest projects there is. I am sort of on intermedia projects, this Planck with European Space Agency and with some NASA … and I have also some other projects going on, so you have postdocs you’re training there, in the transition between being students and being fulltime researchers. Then graduate students and then I have undergraduates studying research projects with. I even take on high school teachers and students and so. We have an outreach thing which I would show you, just to explain the different paces of the universe. We have high school teachers and undergraduates involved and putting this together on the website, to make it available to high school students. It’s this pipeline where you start training them and until they eventually turn out to be in John’s area where they are doing the work.

You are looking for people who are just fully fledged, ready to go?

John Mather: Yes, we look also for young people that have promise and we hope to bring them in and let them learn the trade of space engineering and space science by working with people that have been doing it before, because there is a special discipline and knowledge about things that are very strange and things you would never think of worrying about for space missions. The fact that you can’t go and fix them ordinarily is a very special challenge for people because it is exactly the opposite of a graduate student project. On a graduate student project is working, you take data and publish your paper, and then you are on to the next one. With the space mission you get it working and then you have to make it work for quite a few months and before you trust it to send it up at the space where there is no hope of repair, usually, so it is a completely different discipline, but one well worth mastering because of the things that one can get only in space.

I imagine people have enormous self-confidence once they are ready for this.

John Mather: I don’t think so, I think we have to have accommodation of confidence and caution. The person who is too confident is dangerous and the person who has no ambition is dangerous. We have to have a mix of the things that are beyond what we can do but can still be proven. This is what we do.

From the perspective of the people who come to work for you, what do you think they look for from you, from your experience of your own scientific evolutions? What do you think makes a good mentor?

John Mather: I think that for me the people that have been mentored are the ones that have a creative process and have some knowledge of a wide variety of fields because the things that we have to do are usually spanning many disciplines. To get something to work in space you have to know a little bit of mechanical engineering, … engineering, electronic engineering, optical engineering, kinetic engineering, communications and to be sufficiently afraid of the environment out there to make sure that you think about all the things that could go wrong with your idea before you proceed. That is what I am looking for, people that have that combination.

George Smoot: It varies with the level, we have graduate students who are looking for their first research experience and get a chance to see what doing science is like and just go forward so they can get recommendations to go to graduate school, it is learning now plus preparing for the next job. With graduate students it is a much more personal and intense experience where they have to come in and learn techniques from you and then take it in their own hands and handle it themselves. Then you have to prepare them to write papers and give talks and go out and find their next job and in fact even the job after that because usually the first job is the … job which is a transition job and then they go into permanent jobs. For postdocs, they are looking for a chance to do research that they can get their name on, give presentations and then go on to the next job, go to a permanent job, so it depends on what level you are on and what’s going on. Sometimes they come because they are very excited about the science, and they don’t even realise that the process is an educational process and a launching into the next phase process.

I suppose that there is a lot more to it than the science, especially with a project like COBE which involves thousands of people, you have a lot of administration and management to do as well. Is that increasingly the case with physics research, do you think, that these skills have to be learned alongside the scientific skills?

John Mather: I think so, although it is hard to learn those in school, one has to learn in a crucible of ‘trial by fire’, I think, you develop them by learning, on a job. Some things I think people learn when they are young, to play as team members and other things you don’t learn until you are actually there.

How did you learn?

John Mather: I learned it by actually being there. No one hands you an instruction book and says ‘This is how you are a leader of a space project’. You are 28 years old and you have never done this before, but this is your job, so you do it.

George Smoot: You could say the same thing of the Nobel Prize. It would be handy if the Nobel Prize announcement also came with a handbook – of what to do, what is going to happen next and so forth. You have to learn and be flexible in these kinds of situations, but in fact it is all about learning, and teaching people how to think and how to react and how to behave. I think that we inherited an era which came from … who was the preses really, with the beginning of big science where you put teams together to solve certain problems that were so challenging and so interesting that many people would want to do. And it comes down to everyone agreeing that the objective is very important, and that was so important for us for COBE, was to do that and part of my job as … to go and give talks to the team and keep them enthusiastic, going to the Vandenberg site, giving talks to the air force people and … people just to make sure that they were motivated. It wasn’t just another job for them, they were going to put the rocket right. We were both very nervous at the time of the launch because it was one of the last rockets and there were rusty parts …

John Mather: Yes, it was quite a job to get the rocket ready.

Because it ended going up on a Delta rocket.

John Mather: It was indeed.

It wasn’t intended that way.

George Smoot: That was not. The fact that Delta line had been discontinued for a while, and there were just parts lying in a warehouse rusting. They dusted them off and assembled the rocket for us – it gives you a lot of confidence.

You must have a lot of power to make that happen as well.

George Smoot: It’s power persuasion, it’s the power that it’s such an exciting attempt and path of adventure to follow. It was the crew who got excited about the fact that we might learn about the Universe, even that we didn’t know what we were going to learn. That’s the challenge and the fact that the scientists were so thrilled about it.

John Mather: They really worked beyond what they ordinarily would be called on because they knew how important it was to so many people.

Was the challenge a disaster and the set back that resulted from that the most challenging part of the project? Was that the bit where you needed the greatest confidence to continue?

John Mather: I think so, because when that happened we didn’t know that we would ever getting a chance to launch the vehicle, so we were dependent on finding a completely different alternative. We were very fortunate that our engineering team found a way to do that and we had to lose half the mass of the pay load in order to get it onto the Delta rocket. We were very fortunate there was a different design that was possible, because the Delta rocket is different from the space shuttle, so was able to do that directly.

George Smoot: What happened, we almost had it all assembled. I still have the pieces, the framework from one of the – my instrument came in three pieces – from one of the three receiver pairs. I still have the framework for what was going to find the Delta, because we had to lose weight and shrink in size, we had to rebuild everything. We took the sensitive instruments out of it, and I saved the pieces and reassembled it in. A student and I reassembled them in the lab late one night, so I still have them in my office.

I think it is interesting to think about how one keeps the motivation going through a disaster like that. I can see that individually you can keep your focus, but you have got this enormous team of people who you need to bring with you. How did you go about making sure that people …

John Mather: I think we depended really on our project management which worked so diligently to find a way, and as soon as there was a hope that there was a launch vehicle people were so thrilled that we could actually go again. As soon as that happened there was no problem, and in the meantime we just thought we were doing our job, we will find a way, so I don’t think we lost a lot of momentum on that.

George Smoot: That was exactly … investigators, you have to believe, you have to keep working, show enthusiasm, and there was a core of the teams, they saw you working, they kept working and the other people kept working although you could see their enthusiasm was down a bit because everybody was nervous. It’s not the only chance but that was the one that affected the whole team, hundreds of people at the same time, and the fact that we were going for it and that we would say the same: We’re going to find a way. Then NASA said: Look, we have to show we can go back in the business and if you guys are willing to push this hard you could be the first. And that was …

John Mather: That was a tremendous boost for us, because we went from not having priority to having top priority. At that point it was possible to finish this job which we had looked so daunting before that.

George Smoot: But then they worked night day. We were running three shifts during that, … scientists had the third shift because they wanted the people who were actually working on the space craft to be there during the day light hours and the people who were checking would be there and then whatever what was left were us.

So you went into a reversed cycle. Preparation for coming to Stockholm.

John Mather: Yes.

George Smoot: Yes

Once you got up there and you measured the cosmic microwave background radiation you, in the telephone interview we conducted in October, described that as “the accumulated trace of everything” which I think that was a lovely way of thinking of it. Could you tell us in more detail what it is that you are actually are looking at?

John Mather: We are looking at what is the remains of the cosmic explosion itself. The heat radiation from the Big Bang is still filling the Universe and it’s still not so faint as all that. It’s about a microwatt per square meter of heat radiation coming at us, but it is equivalent to a temperature of only 2.725º Kelvin, so it’s very cold. Nevertheless, quite right on a cosmic scale. This is the radiation we are looking at, it is the Big Bang itself, and it might have traces in it added later, of things that happened from galaxy formation or any kind of strange things that might have occurred. One of our results was that there wasn’t any surprise, the Universe was simple after the first year, until galaxies formed. That was a primary result that we get from the spectrum and it showed that he Big Bang really was the right picture for the whole story. Then there was a whole other second major results that came from the hot and cold spots that George can tell more about.

Sure. Just focusing on that Big Bang result, the CMB is always with us, so in a sense looking at it, could it be described as looking back in time as a way of travelling in time?

John Mather: Yes, we see the radiation as it was when it was last bumped into a meta particle, so we can see the spatial distribution that way, but the colour of the radiation is much older than that. We see the colour of the radiation as it was established one year after the Big Bang. Although the Universe was still a … it wasn’t changing the colour of the radiation, so we see that particular phase as the earliest we can see with this radiation.

It’s extraordinary to think that one has this window into the past. The observations that you made come from considerably later, form about 300 million years after the formation?

George Smoot: 370 000 years.

Sorry.

George Smoot: John was saying that we get a microwatt per square meter which is a lot of power compared to what you get from radio and tv signals that’s on that same scale. But if you ask how much radiation we’re getting from the Sun, direct sunlight is thousands of watts, it’s a factor of ten to nine billion in US, million I guess in European. The Earth is giving us the same. We had to reject the radiation from the atmosphere and from the Sun and from the Earth and from the Moon at a very high level. That was what I was mentioning to you before, that we had developed special antennas, the approach that I followed and the people was using my instruments which means this careful launching of the waves and the approach that John’s instruments followed, which was the sort of the trumpet horn view, where you smoothly, very carefully define what kind of radiation comes in by the fact that it has travelled all around this curve and come straight in.

Those were really key. It’s not quite as simple as it sounds. What John was seeing as this temperature, 2.72, it turns out that at the time we started thinking about the experiment the prediction from the theorists was that other part than a thousand of variations and those would be the seeds of galaxies and classes of galaxies. By the time COBE actually flew the predictions were down to a part than a …10,000. We found them at a part of 100,000. You can imagine, compared to the Sun and the Eart, these variations were just the answers to themselves. These variations are extremely tiny, it was all of being very careful and checking and that was the impressive thing that the team did – everyone was crosschecking and testing and the precision with which the spectrum was measured, that’s phenomenal and the way we measured the variations is just incredibly small.

The example I used to give is that the Universe is smoother than a billiard ball – you know what a billiard ball is? – it is smoother than a billiard ball, yet we saw the variations in that, that are the seeds for the formation, and we did it very much by using this radiation that if you should turn between the low frequency channels on your tv, you see the hash on the tv, some of that is a noisy receiver, some if that is from the … and some of that is this radiation from the Universe. They are all in the same scale, a rough scale, at the very low frequencies, but sorting all that out and measuring it to this position is a task that took these thousands of people working very hard for a long time and just being very careful. You have to give the team a tremendous amount of credit for the great job they did and the care they took.

Absolutely. And future generations of analysis are possibly going to find yet further information buried in the CMB?

George Smoot: It has already happened. As soon as the COBE made the announcements of the fluctuations there was a tremendous amount of public interest and a large number of … and people came into the field immediately, because they saw that … It was like somebody says There’s gold and amounts over there, there was this rush to go to this and at the time of the announcement I said We’re into the golden age of cosmology. A large number of people came and there have been several tens of experiments to make the measurements and the WMAP satellite and soon the Planck satellite coming up. The WMAP satellite has improved by making more measurements across the whole sky and verifying what COBE saw but also measuring with much greater angular resolution. COBE had these antennas, the beam width here is seven degrees, it’s about a tenth of a radiant, so seven degrees across. With WMAP it is around a quarter of a degree on the sky, so we went from 6,000 pixels to a million pixels. Now there’s a high resolution, so typically you show a picture of a person or of the globe with the continents on it. With COBE you can just see the continents, the five continents. With WMAP you can see the shape of the continents, you can see small islands – you can see Cuba – things like that. It’s just such a change and there’s so much more information there, we’re really learning about the cosmos already.

And that’s adding further refinement to the two main discoveries that you two made. Is there, do you think, a further discovery of the same level in cosmology to be made?

George Smoot: You never know for sure, because it’s a surprise. The one really major new discovery that’s happened since COBE was the discovery that the Universe’s expansion is increasing and it’s accelerating the Universe. We always knew that gravity’s attractive, and the Universe is slowing down and structure is forming and it had to happen that way. But now something has happened, it causes the Universe to speed up and pull apart faster. That accelerating Universe was kind of a surprise out of the blue although it makes our whole model of the Universe fit together much better because it makes the Universe older, because it is going faster now and is … back, you think it is younger. If you realise it had been going slower in the past then it started earlier and I guess time for the formation and the galaxies and the stars and our solar system.

John Mather: There’s more to come then as well, and there are many more things that people want to learn from this radiation. One major topic is called polarisation. We are beginning to measure the polarisation of the radiation and some parts of it come from the processes that happened after the radiation was let loose and the galaxies started to form. There’s another part that people are looking for, they may come from gravitational waves in the very earliest moments, so this is the next tremendous challenge, and the subject is to build an equipment that’s capable of discovering that.

If it is discovered, what will polarisation tell us, for instance?

John Mather: It will tell us about the quantum mechanical processes, what we imagine may have happened in that Big Bang itself.

So it takes us to an earlier point?

John Mather: Yes.

George Smoot: There have been observations of polarisation – you expect some of the polarisation just from the variations of the material – and that has been seen, although not measured very well yet, but then there is a next level which is a different mode. The kind of things thar are lumps of extra materia, they either have radiation flowing out of them or into them and the polarisation lines up that way. But if you have gravity waves, as John just has been mentioning, you can get a handiness because the gravity waves travel this way and is stretching space in this direction so it’s extra handy, you can have twist or rotation or … That mode would be an indicator that you’ve seen gravity waves and that could come from a very early part of the Universe. The ideas of inflation, that Universe had this rapid acceleration in an early part and that was what made the quantum mechanical … stretch them, so that their own galaxy was once a tiny fluctuation and now stretched to astronomical sizes. It’s a beautiful idea and we really like to know if inflation happened or something else happened and how did those variations in the Universe come to be and polarisation is one of the probes that we can use to find that.

John Mather: It’s one of the few that are left actually. We have measured everything that we can measure about some things on the background radiation at large scale. Our dependencies are already so well measured that you can’t measure it better. We’ve measured the spectrum very well although we think we could measure it a hundred times better if anyone cares, but the polarisation is something which could lead us to a new understanding of the forces of Nature. What is exciting for a physicist in the Big Bang is it’s the Nature’s laboratory, where we think all the forces were unified, and the great unified theories of physics would hope to explain how gravity, electromagnetic forces and the two kinds of nuclear forces are really all closely related and all quantised. So far that has not been accomplished, even at a theoretical level, but observationally we have a chance to go observe something about that, so this is one of the reasons that the Big Bang story is so important for physics.

That’s a goof point. The phrase you use ‘if anybody is interested’ makes the question if founding for this of research is improving or getting worse at the moment.

John Mather: In my opinion there’s plenty of funding for things that are really worth doing, but there’s always a competition in process for what is worth doing right now. Projects have to compete, worldwide we have these competitions. I think that the gravity wave and the idea that it would produce polarisation in the background radiation is an idea that is getting some funding and is expected to lead to a NASA mission at some point, maybe an international mission.

I just wanted to move to the question of the Nobel Prize itself and whether the notoriety that that will bring, the other notoriety as you have of course already received many other awards, will be useful to you, you think, in your future work. How do you think it will change things?

George Smoot: It will change things a lot and I have already been down talking to members of the congress and their staff about continuing support for sciences so forth. John and I will go – as a civil servant he is not allowed to talk to people without invitations – but we are going to arrange an invitation either in congress or at the Air and Space Museum to give presentations, so that the people in congress and the … staff will get to hear about what we are doing and how exciting it is and so forth. I think that we have a responsibility not only to attract new young people into science, but to make sure that science remains healthy and goes forward both for the good of our country, but also for the good of the world. That science is an international activity, and it is the situation if we have problems with global climate change or energy crisis we are going to have to have scientists in all the countries talk to their leaders and say Here is what the issue is and here is how we are get together to solve it, and then work it out. Without that scientific advice how are we going to go forward on global problems.

And the Nobel Prize puts you in a better position to be a spokesperson for that.

George Smoot: I already have hundreds of invitations and when I went to congress immediately the staffers wanted to meet with me and it’s clear John has …

John Mather: I get invitations every day.

So the students are going to be neglected a little longer.

George Smoot: They are not going to be neglected, we’ll take care of them, they are future scientists.

I am sure. This year for the first time we invited the public to submit some questions via the internet, and if I might, I was just going to ask you a couple of those questions that came in. Andreas Eriksson from Stockholm has asked how examining the largest scales highest energies longest time periods changed your view of everyday life. Does it?

George Smoot: Every now and then I think what difference will it make in a billion years? Because in the Universe a billion years is just an eye flick. We have had almost 14 billion years so far and we’re only a fraction of the way through what we think of as the normal life history in the Universe. We know it’s going to keep expanding at least for 150 billion years. The sun becomes a star and it dies away and that takes 10 billion years, that’s 7 % of the light. It changes your perspective, just to think that the time it takes light to get from Andromeda to here was the time from which it started out at the time when humans started to evolve. When you start to think about the light that came from far away, it gives you a different perspective of the history. How does it change my everyday life? It changes my perspective, but on the other hand I still like to get a good hot chocolate.

John Mather: I think I have similar reactions to George’s. When I look at physical things in the world, I know their history. I know where the hydrogen and helium came from, and it was not much of that around here, but the carbon and oxygen and nitrogen that we’re made out of came from stars that exploded. When I see nice woodwork or something I think to myself those carbon atoms were some place else in a giant cosmic explosion of a star not so long ago. It also reminds me that our own star is going to burn out itself in another two billion or so and we might find another place to live. Those are matters of scientific and personal perspective, but principally it says life is long, the Universe is long, and we need to take long term perspectives to manage our lives here on Earth. We’re like the gardeners here on the planet and we have to plan for a long future.

George Smoot: It’s a question you say if you understand how things work, like a rainbow or you have a little bit of oil on the ground and it rains and you get this nice colour scheme, does understanding how that works take away from the beauty or enhance it? Generally I think it enhances it. Knowing that a tree which looks like this wonderful mysterious thing hasn’t been there forever. That it came … you know, the planet hasn’t been here forever. That doesn’t take away from the fact that when you walk through the forest it’s an incredible experience. And hiking is just you feel a good home.

John Mather: I also feel that what we’re looking at is completely mysterious. Even though we have the stories of science about how this all happens, the individual expression of everything is not explainable. The fact that we look the way that we do is more or less accidental, the fact that particular chance encounters have led to our particular lives and discoveries that we’ve made. None of that is really explainable so life is just as mysterious now as it ever would have been.

Moving on to the unexplainable for the last question. Vijay Krishna Gryalaru from California wants to know what you tell curious kids if they ask you what happened before the Big Bang.

John Mather: I’d say that’s a really good question and science has not answered the question. We don’t know if it’s even a meaningful question because we don’t know whether there were any such things as space and time before the Big Bang. But on the other hand, mathematicians and physicists are working on the question and it’s a thing that we hope to be able to answer sometime, and George has had lots of interesting things to say about this too.

George Smoot: It’s a problem that I’ve been interested in because not surprisingly, many people have asked this question. One of the hardest things that people, they just can’t accept the fact there couldn’t be time before the beginning. The idea that time doesn’t go back forever is alienable. You try and give them examples like try and go past the North Pole, try and go north of the North Pole or something. You try and give those examples and it’s unsatisfying for people, even though you can understand that if you keep heading north, which is like going back in time, there comes a point where you’re going forward in time. You can construct the universe like that. But in fact, there are lots of alternatives out there where going back in time doesn’t mix, it’s like a random walk. There are a lot of people working on various models where there might have been something going on before our particular part of the universe bubbled into a Big Bang and you don’t know what the answer is and you know the Big Bang is going to confuse. It’s like somebody’s torched the place and set fire to it. The clues are very hidden after that, but occasionally when you’re experts on our sun, you can figure out whether it was burned by mistake or by accident. That’s what scientists are trying to do, they’re trying to pose the question in the most general way, even including making the most general laws of physics and see what kind of universes you get, and some of the things I think are quite successful, some of the things like you had in the early days of quantum mechanics and the Copenhagen School. Some of the stuff makes a lot of sense and they’re good rules, and some of it is just mysterious mumbo jumbo because nobody knows what’s going on, and it’ll sort itself out.

Unfortunately, time doesn’t go on forever either and we’ve come to the end of our time today, so it just remains for me to thank you very much indeed for taking the time to talk to us and to congratulate you both once again.

George Smoot: Thank you very much Adam, it’s a pleasure.

John Mather: Thank you. We appreciate it.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

John C. Mather – Podcast

Nobel Prize Conversations

”I don’t think it’s my job or anybody’s job to try to convince other people of the righteousness of my opinion. I think it’s each person’s job to figure out how they look at the world”

Listen to a podcast with astrophysicist John Mather, where he speaks about space and if we will be going to Mars in the future. Mather also shares good advice to young researchers on how to prioritise projects. The movie ’Gravity’ is another topic that comes up – how scientifically accurate is that movie?

Listen as we take you back to this conversation with Mather, recorded in 2014 as part of the series ‘Nobel Prize talks’. The host of this podcast is nobelprize.org’s Adam Smith, joined by Clare Brilliant.

Below you find a transcript of the podcast interview. The transcript was created using speech recognition software. While it has been reviewed by human transcribers, it may contain errors.

Clare Brilliant: Welcome to Nobel Prize Conversations. I’m Claire. Brilliant and I’m here with our host Adam Smith. Hi, Adam.

Adam Smith: Hello, Clare.

Brilliant: We’ve been digging through our archives of previously recorded conversations, and today we’ll be hearing from John Mather. When did you speak to him, Adam?

Smith: The conversation was recorded in 2014. He’d been awarded the Nobel Prize in physics back in 2006 of his work on the Coase satellite and mapping the cosmic microwave background radiation. In 2014, he was busy with another satellite.

Brilliant: I guess he’d had a few years to get used to the prize.

Smith: Yes. he had indeed, the prize tended not to interfere too much in his work because he’s very focused and putting together these teams that have to get satellites to actually work, get launched and work in space.

Brilliant: I think that really comes across in the conversation, the immense task of bringing these huge teams of people together and how dedicated he’s to that.

Smith: Exactly. He was building the James Webb Space telescope back in 2014 which now of course has been launched and is sitting a million miles from earth mapping deep regions of space and revealing all sorts of amazing things.

Brilliant: Yes. It was really interesting to him talk about the potential of what he thinks these satellites are going to tell us.

Smith: Absolutely. I mean, the data’s coming back now and showing that water in the atmosphere of exoplanets orbiting stars in distant constellations or indeed the signatures of carbon containing molecules in those atmospheres. He feels that such signatures will be the footprint of life elsewhere. We will eventually find.

Brilliant: I really found it fascinating, his conviction that we will find extra-terrestrial life.

Smith: I also love his observation that extraterrestrial life may, if it becomes advanced, actually not emit much of a signal that he says, although we beam energy into space all the time, that may be just a stage in our lack of advancement, and once we get past this stage, we might become quieter, if you see what I mean. Fascinating.

Brilliant: Really fascinating.

Smith: Yes. He says that he can’t ever remember not wanting to be a scientist, and you can certainly tell that from listening to him. So let’s tune into the episode now.

MUSIC

John Mather: Morning.

Smith: You’ve just come back from the Intel Science and Engineering Fair in Los Angeles.

Mather: Yes, indeed. It was a pretty amazing group of young people there. Very inventive, very creative, very self-propelled young people. Several of them told me no, they did it themselves. Their parents didn’t even understand what they had done. If the world is to be based on what these young people are doing, we’re in fine shape.

Smith: That’s the thing. In a way one might associate doing science projects with a sort of old fashioned approach. Certainly lots of the laureates we speak to did great science projects when they were young. But nowadays it’s really good to hear that young people are still doing science projects in their spare time.

Mather: Oh, well, yes. They just want to do these things. They think of something, they’re inspired. They look things up on the internet. They take online courses. They go far beyond what their school teachers are leading them to do. They’re amazing.

Smith: It’s been going a long time, this science fair, but it’s becoming a more and more international affair. Is that right?

Mather: Yes. I think they told me there were 1600 people from 80 countries. Yes, it’s indeed huge.

Smith: Anybody you saw you wanted to recruit?

Mather: Oh, there are lots of really smart people there. One of the astronomers that I know is already going to be a summer intern at NASA Goddard where I work. We certainly recruit right people occasionally, but before that we’re ready to hire them into NASA we need them to have college degrees mostly.

Smith: Yes.

Mather: Of course. We’re just eager to see what they’re going to do next.

Smith: Did you tinker with science projects when you were young?

Mather: Yes, I participated in some. I know in ninth grade I had a project about nutrition and rats. I kept eight baby rats under the table in the kitchen for a few weeks while I found out what they did on different kinds of food. Later on, I think in 11th grade, I had a project about trying to measure the orbits of asteroids. I would say that it was a complete failure, but it was fun to try.

Smith: Were there any mishaps with your projects apart from failures, actual disasters?

Mather: No. No serious disasters. Nobody hurt.

Smith: Were you in a very supportive scientific environment when you were doing these things? Or were you out on your own?

Mather: Yes and no. My dad is a scientist, so he certainly was encouraging. My mother was encouraging, but they didn’t know personally very much about what I wanted to do. My dad did teach me statistics in ninth grade, so I learned about analysis of variance from him. That was a good thing to know about. My other project was asteroid orbit. Now I was definitely on my own.

Smith: When you were doing these things, had you already decided that you wanted to become a scientist?

Mather: I don’t know if I ever decided that. I think it’s more like I noticed that. I can’t remember ever not wanting to be a scientist.

Smith: Really. Even when you were very young?

Mather: I don’t remember anything when I was very young, but I know around third or fourth grade, I was already reading everything I could about science.

Smith: Gosh. So that’s eight or nine years old and you were already… Wow. That must’ve been pretty unusual.

Mather: I suppose so. But I have no way to tell. I would expect that many of the science fair students there also started there when they were eight or nine years old.

Smith: Can you summarise what it is about science that you found and find so fascinating?

Mather: Several things. One is that there’s a sense of discovery that you can just find out things that nobody knows before. If you find them yourself, and you’re the first one to find them, that sounds really important. Maybe it’ll help change the world for the better in some way. This idea that it’s also a little dangerous. I grew up on stories of Galileo and Darwin and the fact that they got in trouble just proved to me that it was important.

Smith: I love the idea of a nine-year-old boy reading about science and thinking of it as a kind of wonderful, dangerous profession.

Mather: Growing up here in the States where there’s so many fundamentalists around and people who would disagree with you if you wanted to tell them about evolution. I used to have dreams about that. Suppose I were teaching in school and I was teaching the students about evolution. It wasn’t so long ago we had our trial, jury trial over here about whether it was okay to teach evolution. Anyway, we keep on fighting that fight.

Smith: Exactly. Because things haven’t changed all that much. I mean, they’re not jury trials now, but there’s still a big debate.

Mather: Yes.

Smith: Do you still feel yourself to be fighting that battle on a daily basis to try and get people to attention?

Mather: Actually, no. I don’t fight it on a daily basis. I just do what I do. I don’t think it’s my job or anybody’s job to try to convince other people of the righteousness of my opinion. I think it’s each person’s job to figure out how they look at the world.

MUSIC

Smith: One of the things that you had to have when you eventually came to be the lead scientist, making sure that the Kobe Satellite Project actually worked was an incredible degree amount of confidence, I would’ve thought.

Mather: I actually don’t think so. Confidence, I think, is the sort of wrong feeling to convey. I think more it’s a sense of the importance of the work and the determination to make it to work. So rather than confidence, one has to have persistence and determination and certain degree of worry. If you don’t worry, then you don’t understand how hard the job is. In fact, it’s the job of our space engineering experts to make sure that something works. They have to spend a vast amount of effort to think of everything that could go wrong and make sure that doesn’t happen. It’s like the opposite of confidence.

Smith: Okay. But when somebody handed you the task of pulling all these people together and acting as the kind of center point for everybody, building Kobe, putting everyone in the same direction. They must have seen in you the sort of person who could inspire confidence in others, at least.

Mather: Yes. I guess they must have. It’s hard for me to remember those days. When I was hired into NASA to work on this project I was only 30 years old. So I thought they don’t have much basis for confidence. It’s just I’m willing to stand here and say I’m going to do this project. They were willing to bring in the top talent to make it happen. I didn’t actually organise all of that. Top engineering management did that. I think what they saw was a young team of scientists with some good ideas, and they thought it was important enough to recruit the best engineers that they could to make sure that it would happen. So it’s much more an organisational process with other people’s leadership than it is me.

Smith: Right. Is that, in a way, the secret of NASA’s success? That they’re able to organise the right teams of people to make these projects work?

Mather: Yes, I think so. It’s NASA, it’s every other large organisation that succeeds has to have a set of people and a culture and a process that leads to success. If you were to just set one bright person in the middle of the world and say now build me a telescope it would be a very long time of recruiting the top talent and organising them to find out who could do what and making sure that things would work. An organisation like NASA or its great contractors, all of them have this collection of people and process at the same time. There’s no way we could be building a great telescope today, just because a few people were smart. It takes this huge crowd of people with history who know how to do things.

Smith: When you finished the project, when Cobe finally delivered, in your case, the evidence that the CMBR had a black body form, do you remember the moment of finishing that project, of the data coming in?

Mather: Well yes and no. There are a number of special moments. One is of course the launch. And you realise that no, it did not explode.

Smith: Yes.

Mather: Then a few hours later, you realise and signals have come back and you say, well, the satellite’s alive. Then it takes a few days before we are able to open the cover on the hibi cryostat to find out if everything works. Then two days after that things are not behaving quite right. We have to debug and figure out what to do about all that. But within a couple of weeks, I think we were already getting our first interferogram and our first data saying, yes, things are functioning. I do have somewhere in my keepsakes a signed interferogram where my team members working late into the night were able to make a printout that showed the data were coming in correctly. That’s a special moment. It didn’t take too long after that before we realised we could make the famous spectrum that we presented six weeks after launch at the Astronomical Society.

Mather: I think when I presented that spectrum and we got a standing ovation for it, I came to understand that it was much more important than I had ever guessed. That was pretty special. Then two years later, as you know, we put forward our first maps of the sky. Again it was hugely important to the world because it was a map that they could print on the front end of the newspaper, and it was got even more publicity than before. I’d like to, by the way, mention that there was a process leading to that. About six months before that event Ned Wright, who was a member of our science team, had done his own personal analysis of the microwave map, and showed the science team that yes, it had spots on it. Our conclusion was that’s probably right, but we better check it. We spent the next six months verifying that it was correct before we could go public with it.

Smith: That six months was important.

Mather: Yes. There’s a history of people going off half-cocked in science. The more important it is, the less careful they get sometimes. That was in the days of poly water, which was apparently a fraud and cold fusion, which was apparently another fraud. We knew for sure we’d better not be announcing something that would have to be retracted. That’s why we were so careful.

Smith: When you come to the end of a project like that, and you had lived with a cosmic microwave background radiation for a long time, because you’d tried to make a map from balloon borne experiments prior to you ever beginning on the satellite project. When you come to the end of it, it must be very hard to conceive of starting something else. You finished a major chunk of your life’s work. How do you begin again?

Mather: That was a tricky question. At the end of the Kobe project, I did indeed think, what am I going to do now? I started poking around at different ideas. I thought for a while, well, maybe you know, they were planning the Spitzer Telescope at the time. My friend said, well, you know, it’s not a big enough telescope. We need to make a bigger one. I started making sketches of how you would unfold a telescope in outer space. I had in mind something only about two meters across, which was about a little over twice what the size of Spitzer Telescope is. So I thought, well, that would be fun. I presented my ideas to a small colloquium, and my friend said, oh, we’ll never do that. That’s much too hard. A couple years after that, I got a phone call from NASA headquarters that it said, it’s time to start the new telescope. What turned into the James Webb Space Telescope would I like to participate. They needed a proposal the next day for how to proceed. So I thought, I certainly can tell what’s to do now.

Smith: Did you have your scrap of paper where you had your doodles ready?

Mather: Yes.

Smith: When will the James Webb Space telescope launch?

Mather: It’s planned for October, 2018. So just over four years from now. We will have the observatory at the launch site. That’s the plan.

Smith: And the launch site will be where?

Mather: It’s in French Biana. It’s on the equator in South America because the European Space Agency is buying the rocket for this mission, and that’s where they launch.

Smith: How assured is that rocket launch? Is there a huge competition for those, or can you really book in advance like that and say, this is going to be a model?

Mather: No, we can book those in advance. It’s a commercial product. They launch them many times a year. I think they have a track record of about 50 in a row, good runs. We’re pretty pleased with that. It’s about as good as it gets in the space business.

Smith: Do you have a kind of backup plan for if you happen to be the rocket that does explode?

Mather: No. We don’t even think about that.

Smith: Okay, let’s not talk about that.

Mather: Better not to think about that. Just make sure the one that we have does the right thing.

Smith: Okay. When it gets into space and becomes functional, what will it see that hasn’t been seen before?

Mather: It’s designed to do infrared astronomy, which we accomplished by making the telescope cold so it doesn’t emit infrared light itself. It’s also very large. It’ll be able to look much farther out into space and farther back in time to look for the first objects that formed after the Big Bang, the first stars, the first galaxies, the first black holes, the first supernova, the first everything. Then try to understand how that led to our existence today. How did the stars explode and the material fall back into make new generations of stars and planets? How are stars being formed today? We know where they’re doing it nearby, and so let’s please have a look inside those dust clouds, see them do it. Ideally to learn a lot more about planets planetary systems. So for instance tracking down all the planets that have been discovered by the Kepler. We’re even developing a NASA mission called Tess, which is a transiting exoplanet survey satellite, I think. Anyway, it will basically extend the Kepler technique to all the nearest and brightest stars so that with luck, we’ll have a pretty nearby candidate object that might be like Earth. If we are extremely lucky, then we will find one that has enough water vapor to have an ocean, and that will be remarkable.

Smith: From the James Webb, you are going to be able to see planets as they transit across their stars and tell whether they have enough water vapor to potentially have oceans.

Mather: Yes. Isn’t that amazing?

Smith: It’s indeed.

Mather: When we first conceived the telescope, we didn’t know that was possible. We’ve only made the tiniest design changes to make it possible for the telescope to see those things.

Smith: Is it the case that you have a kind of raft of ideas coming in all the time for how you can improve it, and what else you can add to it to the mission? Do you have to have a shutdown time at which you say, after this point, no more ideas, let’s just do what we’re doing.

Mather: Pretty much the scientific requirements were frozen in about 2002. So hardly any changes have been made since.

Smith: That’s amazing. That’s a very long time. Why does it have to be set so far ahead of the 2018 launch?

Mather: Well, of course, in 2002, we didn’t think the launch would be in 2018. We thought we had much shorter time. But it was still the correct plan because you can’t build stuff while you keep changing your mind. So you have to decide what you’re going to do. So we did, however, have to continue to demonstrate our technologies. We had 10 different things that had to be invented and perfected before we could use them on this observatory. It took until 2007 before they were even ready to trust. That included things like the mirrors, the two kinds of infrared detectors that we need, a very low temperature amplifier and a computer to run the detectors. The ability to unfold the telescope in space and focus it after launch, all of those things had to be understood before you could even finish the design. So it’s very intimidating. There’s a plenty of good reason why you don’t keep changing your mind.

Smith: When people talk about the Apollo missions in the sixties, they look back and they say that it was an unbelievable feat. It happened, but the advancement in technology in the lead up to the moon missions was so great that it was just unlike any kind of invention that had been seen before or pace of invention. Is it like that every time you do one of these, that you conceive things that have to be invented to make this project work? It seems incredible when you conceive them that it can be done within the time, but somehow people find the resources to make it happen?

Mather: I don’t know about every time because every mission is different. We have different requirements, for instance for studying the earth than we do for doing astronomy. For earth science we need to have continuity where we know that the new equipment agrees with the old equipment as measuring trends of the earth is very important. You want to know if it’s getting warmer or colder, wetter or drier, dusty or less dusty. All those things require continuity. For that territory sometimes less change is good. Many more of the same kinds of equipment is good for astronomy. We push the frontiers by building something that’s more powerful than before. They’re infrequent enough that technology changes a lot in between. For instance the next even bigger telescope after the James Webb Telescope would probably be built specifically optimised to study those planets around other stars, the exoplanets. That probably means it needs to be two or three times as large as the James Webb telescope. When we get to do that, it’ll take yet another set of inventions.

Smith: Do you have to start designing the next one before you’ve got the current one up and working so that you have to predict what you’re going to see from this experiment and use that to design the next experiment without actually knowing whether this one is going to give you what you need?

Mather: I think actually our challenge is a little different. The most uncertain thing about these great telescopes is can we do them? People are quite concerned about what happens if it doesn’t work. I think that’s the number one thing to establish that it’s possible for an organisation to produce a working product, even if it is complicated. I think setting out the next kind of science to do isn’t actually so hard to figure out because we already have good evidence for what it should be.

MUSIC

Smith: How do you decide which experiments to do? How do you prioritise and given the vast number of possibilities, and whether NASA or invest in space missions or whether they invest in satellite technology? How do you begin to decide?

Mather: For a particular mission like the James Webb telescope we set out committees of scientists to say, well, what’s most important to you? What do you think we’ll be wanting to do in 10 or 20 or 30 years from now? How do you know that somebody else isn’t going to do it? We looked for the things that could never be done in any other way. That sort of basic idea, don’t do something somebody else can do. It’s too hard and takes too long to cut up a space mission. We could tell that nobody was going to do this particular science because nobody could see through the earth atmosphere at the wavelength that we were working on. Whatever progress that was going to be done, had to be done with a space mission. That told us our idea was unique. That’s if you want to say, how do you choose what general idea to pursue what kind of observatory? We have giant committees in the US. They meet every 10 years. They produce a survey of all kinds of astronomy and what should be done next. Europe has its own process for doing those things and so do individual countries like the UK. Committees of scientists get together and argue. That’s a good thing.

Smith: Is there a big debate about whether it’s better to do missions that have great popular appeal? I suppose searching for exoplanets is a good one as far as the public are concerned. Certainly putting people onto Mars would have popular appeal or projects that are more for the scientist, if you like, where the popular appeal is not quite so obvious.

Mather: I don’t know. Clearly the public pays for these things with their taxes for large NASA and European missions. If we’re sending people to Mars, it may happen differently because it takes a different way to go than what we’ve been thinking about. For instance there’s a company called SpaceX where they’ve been making good progress on lowering the price of space launches. The company owner, Mr. Elon Musk, says that he’s motivated by the desire to go personally to Mars. That may actually change our whole interplanetary travel process if he’s successful.

Smith: Do you think he will be?

Mather: He is doing awfully well now, so I encouraged the thought that he can do well. Travel to Mars is dangerous no matter how you think of it. But we can do better. So maybe we will.

Smith: Did you ever entertain the thought yourself of trying to get up into space?

Mather: Not very much. I’m not very much of an athlete. I think I would be a little concerned about surviving the launch, but if I could go safely and comfortably, of course, I would want to go.

Smith: I wanted to ask you just one film related question. Having watched Gravity on an airplane journey myself the other day, is that picture that’s portrayed in the film, gravity of a rather crowded near Earth orbit with a potential of things to bump into each other, satellites bump into each other, becoming true? Are we getting a bit crowded in the near Earth space?

Mather: It is crowded, and we’ve already had a one definite accident where two satellites collided, and they weren’t even trying. They were just a random accident. Of course, that showers the area with debris. We’ve had a couple of events where satellites were intentionally shot at by the people that owned them, one US to prove the ability to do it and one Chinese. In both cases debris occurs and this has a significant hazard for astronauts. There’s more and more of this debris up there. It’s not imminent, but certainly it’s predictable that there will be a time when there’s so much debris that you can’t go there anymore.

Smith: That will happen? There will be such a time?

Mather: It depends on what people do. We could continue to work on ways of reducing that debris to go out and catch it or destroy it, or send it into the atmosphere, or various things we could do that would help.

Smith: Hard to conceive, because…

Mather: Now you probably already know that there’s an international treaty that requires all satellites in those areas to be disposed of safely when they’re done. But bad things still happen.

Smith: I can’t begin to see how you might, you might begin to get rid of the debris. You’d need some sort of vast vacuum cleaner sucking it all up.

Mather: Yes, you do. There are a lot of ideas but none of them turned out to be very… none have been chosen yet, I think.

Smith: I mean, presumably it’s a very important problem to solve, because otherwise you also can’t put satellites up because they’re gonna bump into the debris every so often.

Mather: Yeah. It’s harder than it sounds. Let’s put it that way.

Smith: Yes, quite so. One of the other things you spoke about with reference to James Webb, was that it’s going to look further back in time to the formation of some of the earliest large structures in the universe. That’s an extraordinary thing to sort of begin to conceive. I wanted to ask, do you stop every so often and just marvel at the wonder of what you are looking at and what you’re trying to look at? The enormity of it?

Mather: I do every day. I’m thinking about the marvels of what I’m looking at. To me, the even more mysterious part is the biological world. I’ve studied physics long enough to have some idea of how these things function and how we’re now able to simulate in the computers how galaxies form and things like that. How stars form how planets form. When I listen to my biologist friends talk about what they’re working on, I’m thinking how completely astonishing it all is and how unutterably complex it all is. How almost miraculous it seems, even when you understand about evolution. There’s just no end to the complexity of what we have inside us. To think about the fact that we’re probably all descended from the same original single cell living thing 3.8 billion years ago. Here we are continuing 3.8 billion years of life. So you and I, and the bacteria and the viruses are all direct relatives.

Smith: It’s very nicely said, very beautifully said. But one of the strange things perhaps, is that people in general, I would say are much more grabbed by the wonders of the universe than they are by the wonders of life on Earth. If you look at sort of newspaper headlines, as soon as there’s a new beautiful picture of the universe, or some fact that brings out the enormity of space, it hits headlines and people lap it up. Somehow the marvel of life on Earth is perhaps more mundane to people. They see it, they sort of encounter it every day, and somehow they’re used to it, and they don’t tend to be as amazed by it I would say.

Mather: I know, that’s true. We make beautiful pictures in our astronomy, and people are inspired by those pictures. How life works is just much more complex than you could possibly imagine. So it’s hard to make a pretty picture of it. But if you know a little bit about it, you say, oh, how completely amazing. Because life is more, is far more than I ever knew. It’s done digitally. We have digital code in our RNA and our DNA. The little tiny computer hardware inside each cell, they read the code and do things with it. Things are switched on and off digitally. Nobody gets excited about computer code, except maybe the people who write it. We just are, we just use it without knowing anything about the marvels inside it. People aren’t amazed at the wonderful engineering inside their cars either. But 200 years ago, we didn’t have any. That’s an equally mysterious and wonderful story.

MUSIC

Smith: Is there one undiscovered question in space research in astronomy that you very much hope to see answered in your career?

Mather: I’d say every day when somebody asks me that question, I have a different answer, because there’s so many wonderful mysteries out there. I’ll just say a few that are really intriguing and there’s a chance that we can make some good progress. What are the dark matter and the dark energy? There’s a fair chance that we can have a reaction of some kind of dark matter in a laboratory setting. There are several experiments worldwide hunting for that. Maybe we’ll know more about the dark matter and maybe we’ll finally get a satisfactory unifying theory of physics that says what it is and what it’s supposed to be, and makes some decent predictions that would help the closer to home. Are we the only ones here in the universe, or is this planet the only one that’s alive? Or are there many planets that are alive? I’ll tell you my prediction is that wherever there’s liquid water there’s life. That’s what I think. And how would we know? We have to go a few places where you can examine this. On Mars, there at least was, and probably still is, liquid water in places. I think when we dig carefully and well, we will discover signs of life on Mars. We know we can get there with the equipment to do that.

Smith: Let me just explore that question a little bit more. Where will the liquid water be on Mars, do you think?

Mather: It’s not on the surface because it’s too cold and too dry, but underground, there could be liquid water in the rock.

Smith: When do you think it is likely that we might be able to get to that place?

Mather: Oh, that’s pretty hard. It depends on how far down into the rock you think you might have to drill, or whether you think some signs of it will be on the surface. I think we have to send a continuing series of probes to go looking around. We have chemistry labs on the surface of Mars now. In fact one of them was built right here at Goddard Space Flight Center. My colleagues are every day rehearsing in their lab in Greenbelt, Maryland, how to do the analysis on Mars. There will be a continuing series of miniaturized instruments to go to Mars to do these analyses. Another great hope that that team has there is to bring back some rocks so we can study them here at home, with even more powerful equipment. Bringing rocks home, that’s clearly a major job. It’s difficult and expensive also, but it’s still not nearly as difficult and expensive as getting people to Mars and back. I think it’s clearly a next step in our in our travel plan to Mars is to learn how to go there with robots and bring back rocks for study.

Smith: Sorry, now that we’re on this topic of extra terrestrial life, and given that you surely expect to find liquid water on innumerable planets in time, and thus there are innumerable points in the universe where there is life, do you think it’s odd that there has been no sign of that life seen in emissions that we’ve been looking for in space?

Mather: No, I don’t think it’s odd. I think it is what I would expect. There’s no particular reason for a civilization to be transmitting large amounts of radio power out into space. We do it here on earth sort of by accident. We need radars, we have televisions. It wouldn’t surprise me a bit if in another century that we abandoned all that stuff because there’s some other better way to do it. I think it’s quite possible that if there are civilisations out there carrying on a high technology civilisation that there’s no reason for them to be sending us a signal.

Smith: Yes. It’s very hard to think of things in any other way than the way you live, isn’t it? So I suppose, all future predictions sort of see us going on just as we are, but we won’t be.

Mather: Anyway, I think space is also very large. I think that there’s a suggestion here that even if life is common, that intelligent life is not common. The evidence that we have here on Earth is that very soon after the asteroid bombardment ended about 3.8 billion years ago we got signs of life in the fossils. Probably it was very quick here after life could occur with liquid water that we had. So that says the formation of life is quick, but then it took the rest of history for us to get here. Modern civilisation has only been here, maybe you call it a hundred years, where we could transmit radio power which out of the age of the universe is just like nothing. We’re so new and so brief here, it’s hard to tell where we can go or what we will do.

Smith: Yes. It is a good point that, what is it? Is it three and a half billion years since life first began on Earth, perhaps? How would that compare to the normal time that it would take an intelligent civilisation to occur on any planet? How long do planets normally have before something happens?

Mather: Right. Good question. No one doesn’t know. We have our only one case that we’ve noticed, which is ourselves. There are many serious writers who think that our case is rare. There’s a book called ‘Rare Earth’ that makes the case for that. That’s not the only one. I think they’re probably right that the history of events here on the surface of the earth is unusual. We have a particularly unusual situation with a large moon, which stabilises the spin axis of the earth. We have volcanism and continental drift and just the right amount of water to have both land and ocean. Those might all be necessary for the formation of intelligent life. We don’t know, but what if all those are necessary, then it would be rare.

Smith: Do you think you might see extraterrestrial life on Mars in your lifetime?

Mather: I think quite so. I think we could but I don’t know. Because Mars is large, if you were to sit down a probe in the desert here on earth, you might have a hard time discovering that there was something underground that was alive here too.

Smith: Yes.

Mather: Each probe can only examine a few square meters of territory at that, out of millions of square kilometers. If you don’t find it the first time, it doesn’t mean there’s none. It just means you didn’t find it.

Adam Smith: I suppose every scientist likes to point out how each time you ask a question, the answer just leads to more questions. It couldn’t be more true in the case of astronomy and space exploration and cosmology.

Mather: Certainly true. Absolutely. But that’s one of the great marvels of science too, that when you see a little farther, you see that everything is more complex. I think it’s a fair guide to science to figure everything is more complex than you can possibly imagine. If you can just peel off another layer you’ll have more work to do.

Smith: Yes. That’s a great advertisement for a career in science, isn’t it?

Mather: Yes. Our job is not going to be done anytime soon.

Smith: Good. What a fascinating conversation. At least for me. I’ve enjoyed it tremendously.

Mather: Thank you, Adam. I love talking with you.

Smith: Thank you so much.

MUSIC

Brilliant: This podcast was presented by Nobel Prize Conversations. If you’d like to know more about John Mather, you can go to nobelprize.org. Where you’ll find a wealth of information about the prizes and the people behind the discoveries.

Nobel Prize Conversations is a podcast series with Adam Smith, a co-production of FILT and Nobel Prize Outreach. The producer for Nobel Prize Talks was Magnus Gylje. The editorial team for this encore production includes Andrew Hart, Olivia Lundqvist and me, Clare Brilliant. Music by Epidemic Sound. You can find previous seasons and conversations on Acast or wherever you listen to podcasts. Thanks for listening.

Nobel Prize Conversations is produced in cooperation with Fundación Ramón Areces.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Speed read: By dawn’s early light

The 100th Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to John Mather and George Smoot for recording faint echoes of the birth of the universe. Their precise satellite measurements of the cosmic background radiation, remnants of the sea of light emitted by the new universe, have confirmed fundamental predictions arising from the Big Bang theory, leading to its further acceptance as the standard model of cosmology.

The possibility that the universe began in an explosive burst was first seriously suggested in the 1920s, an idea sarcastically dubbed the ‘Big Bang’ theory by Fred Hoyle, a critic of the theory, in 1949. About the same time it came to be realized that if the dawn of the universe was indeed explosive, then a faint afterglow of this explosion might still remain, and be detectable. In 1964, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson realized that microwave background radiation flooding into their radio receivers was indeed such a signature of the Big Bang. Owing to the interference caused by earth’s atmosphere, however, it was impossible to see this radiation unimpeded.

In 1989, fifteen years after it was first proposed, NASA’s COBE satellite was launched under John Mather’s leadership to study cosmic microwave background radiation from orbit. Within minutes of starting its recordings, it confirmed that this diffuse radiation displayed precisely the expected frequency – wavelength relationships – the perfect ‘blackbody’ spectrum predicted to result from first light in the universe. In subsequent measurements, detectors on the COBE satellite under the direction of George Smoot were able to measure minute variations, or ‘anisotropies’, in the background radiation that are the faint whispers left behind by developing clusters in the expanding universe. Such traces of the earliest clumps of matter, which later went on to form large-scale objects such as galaxies and galactic clusters, were another key prediction of Big Bang theory.

There may yet be further cosmological evidence locked up in the cosmic microwave background radiation, and it is still the object of intense investigation – for instance, by NASA’s current Wilkinson microwave anisotropy probe (WMAP) satellite and the European Space Agency’s upcoming Planck mission, scheduled for launch next year.

George F. Smoot – Prize presentation

John C. Mather – Nobel Lecture

John C. Mather delivered his Nobel Lecture 8 December 2006, at Aula Magna, Stockholm University, where he was introduced by Professor Per Carlson, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

Summary: The story of the COBE satellite mission began in 1974. The successful launch in 1989 was a landmark for modern cosmology. The spectrum of the cosmic microwave background radiation was shown to follow very precisely a black body form with a temperature of 2.725 K, giving strong support for the Big Bang theory of the Universe.

John Mather held his Nobel Lecture December 8, 2006, at Aula Magna, Stockholm University. He was presented by Professor Per Carlson, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

Lecture Slides

Pdf 3.87 MB

Copyright © John C. Mather 2006

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 528 kB

George F. Smoot – Nobel Lecture

George Smoot held his Nobel Lecture December 8, 2006, at Aula Magna, Stockholm University. He was presented by Professor Per Carlson, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

Summary: A detailed account is given of the search for anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background radiation. The COBE satellite, launched in 1989, found very small differences between the temperatures of the cosmic microwave background radiation in different directions. Small fluctuations, of the order of parts per million, were found. These are expected to make up the seed for the formation of structures in the galaxy, giving strong support for the Big Bang theory.

George Smoot held his Nobel Lecture December 8, 2006, at Aula Magna, Stockholm University. He was presented by Professor Per Carlson, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 1.01 MB

John C. Mather – Other resources

Links to other sites

About John C. Mather from NASA

COBE

Presentation of the COBE Project, NASA

George F. Smoot – Photo gallery

George F. Smoot receiving his Nobel Prize from His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2006.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2006

George F. Smoot after receiving his Nobel Prize at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2006.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2006

George F. Smoot showing his Nobel Prize medal.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2006

Swedish Princess Madeleine and George F. Smoot at the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 2006.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2006

Their Majesties Queen Silvia and King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden (middle) posing with John C. Mather and his wife, Jane Mather (left), and George F. Smoot and Christina Skube (right) at the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 2006.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2006

The Nobel Laureates in Physics and the Royal Swedish siblings. Left to right: Crown Princess Victoria, George F. Smoot, Prince Carl Philip, Christina Skube, Princess Madeleine, John C. Mather, and Jane Mather.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2006

Nobel

Laureate in Physics George F. Smoot in a light moment with

Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden. Behind them is Princess

Madeleine.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2006

All the 2006 Nobel Laureates assembled for a group photo during their visit to the Nobel Foundation, 12 December 2006. Left to right: John C. Mather, Edmund S. Phelps, Roger Kornberg, Dipal Chandra Barua (representing Grameen Bank), Orhan Pamuk, Andrew Z. Fire, Craig C. Mello, Muhammad Yunus, and George F. Smoot.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2006

George F. Smoot during the Nobel Foundation reception at the Nordic Museum in Stockholm, 9 December 2006.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2006

George F. Smoot delivering his Nobel Lecture at the Aula Magna, Stockholm University, December 8, 2006.

George F. Smoot and John C. Mather after delivering their Nobel Lectures at the Aula Magna, Stockholm University, 8 December 2006.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2006

From left: Per Carlson, George F. Smoot and John C. Mather at the Aula Magna, Stockholm University, 8 December 2006.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2006

George F. Smoot (right) and John C. Mather (left), like many

Nobel Laureates before them, autograph a chair at Kafé Satir at the

Nobel Museum in Stockholm, 6 December 2006.

Copyright © The Nobel Museum 2006

Photo: Fredrik Persson

John C. Mather (left) and George F. Smoot (middle) at the interview in Stockholm, 6 December 2006. The interviewer is Adam Smith, Editor-in-Chief of Nobelprize.org.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2006

George F. Smoot demonstrating the history of the universe at the interview in Stockholm, 6 December 2006.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2006

George F. Smoot at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, California.

Copyright © Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory 2006

Photo: Roy Kaltschmidt