Elie Wiesel was born in 1928 in the town of Sighet, now part of Romania. During World War II, he, with his family and other Jews from the area, were deported to the German concentration and extermination camps, where his parents and little sister perished. Wiesel and his two older sisters survived …

Elie Wiesel – Speed read

Elie Wiesel was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work as the world’s leading spokesman on the Holocaust.

Full name: Elie Wiesel

Born: 30 September 1928, Sighet, Romania

Died: 2 July 2016, New York, NY, USA

Date awarded: 14 October 1986

Witness and messenger

Jewish author, philosopher and humanist Elie Wiesel has made it his duty to bear witness to the sufferings of the Jewish people, to ensure that the world will never forget the Nazi-led genocide. Wiesel and his family were interned in concentration camps in Poland and Germany during WWII. The family was separated, and Wiesel lost his parents and a sister. An eyewitness to the carnage of the Nazis, Elie Wiesel is one of the world’s leading chroniclers of the story of the Holocaust. His message to people today: Fight indifference! Accordingly, Wiesel has voiced his support to persecuted and oppressed contemporaries, such as the victims of apartheid in South Africa.

| Holocaust The Nazi extermination of the Jewish people during WWII. The decision to implement “the final solution,” mass killing by gassing in specially-designed facilities, was taken at a meeting in Berlin in January 1942. Some six million Jews were murdered. |

”The Nobel Committee believes it is vital that we have such guides in an age when terror, repression, and racial discrimination still exist in the world.”

Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee Egil Aarvik, Presentation Speech, 10 December 1986.

In the death camps

Elie Wiesel turned 16 in 1944, the year disaster struck the Jews of Sighet, Romania, which was part of Hungary at the time. Aided by Hungarian police, Hitler’s troops entered the town, arresting its 15,000 Jews. The Wiesels were sent to Auschwitz, a death camp in Poland, where Wiesel’s’s mother and a sister perished in the gas chamber. He and his father were sent from there to Buchenwald, a concentration camp in Germany, where his father died of starvation and dysentery. Young Elie Wiesel was emaciated and close to death when American soldiers liberated the camp in April 1945.

Journalist and author

Rooted in the Jewish storytelling tradition, Elie Wiesel became a writer at an early age. After the war, he studied literature and philosophy at the Sorbonne in Paris. This formed the foundation for his career in journalism, which shortly after became his livelihood. It is as a witness to the extermination of the Jews that Wiesel’s prominence as author and person emerged. He forced himself to wait ten years before writing about his experiences in order to distance himself from the atrocities. He first published La Nuit (Night) in 1958. The book is a gripping eyewitness account of the Nazi-led genocide.

The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity

Wiesel donated his peace prize money to the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity, established in 1987. The foundation’s mission is to promote human rights and peace by bringing together creative people at conferences to discuss pressing ethical issues. Together with the Norwegian Nobel Institute, Wiesel hosted one such conference, “The Anatomy of Hate”, in Oslo in 1990. The conference was well attended, and gathered together other leaders of the peace effort, including Nelson Mandela, Jimmy Carter, Yelena Bonner, Nadine Gordimer, Vaclav Havel and Günter Grass.

| Humanist A person who emphasizes the worth and dignity of the individual and who seeks to cultivate the values and philosophy of life that lead to the most fulfilling existence for human beings in their lives on earth. |

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Elie Wiesel – Photo gallery

Elie Wiesel attending the Nobel Centennial 2001, a conference titled ”The Conflicts of the 20th Century and the Solutions for the 21st Century” in Oslo, Norway, December 2001.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

At the Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony on 10 December 2001 where Kofi Annan and the United Nations were awarded the 2001 peace prize, many previous laureates were present. From left: Joseph Rotblat, Jody Williams, José Ramos-Horta, Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, Lech Wałęsa, Desmond Tutu, John Hume, David Trimble, Elie Wiesel, Norman Borlaug, Rigoberta Menchu Tum and Mairead Corrigan. The remaining are representatives for peace prize awarded organisations.

© Knudsens fotosenter/Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum.

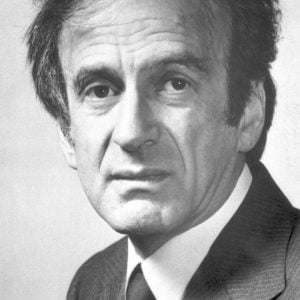

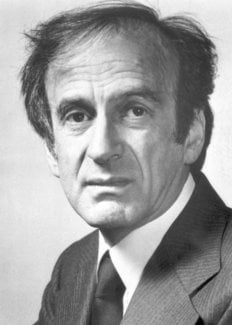

Author, philosopher and humanist Elie Wiesel at his work desk in November 1980.

Photo by Santi Visalli/Getty Images

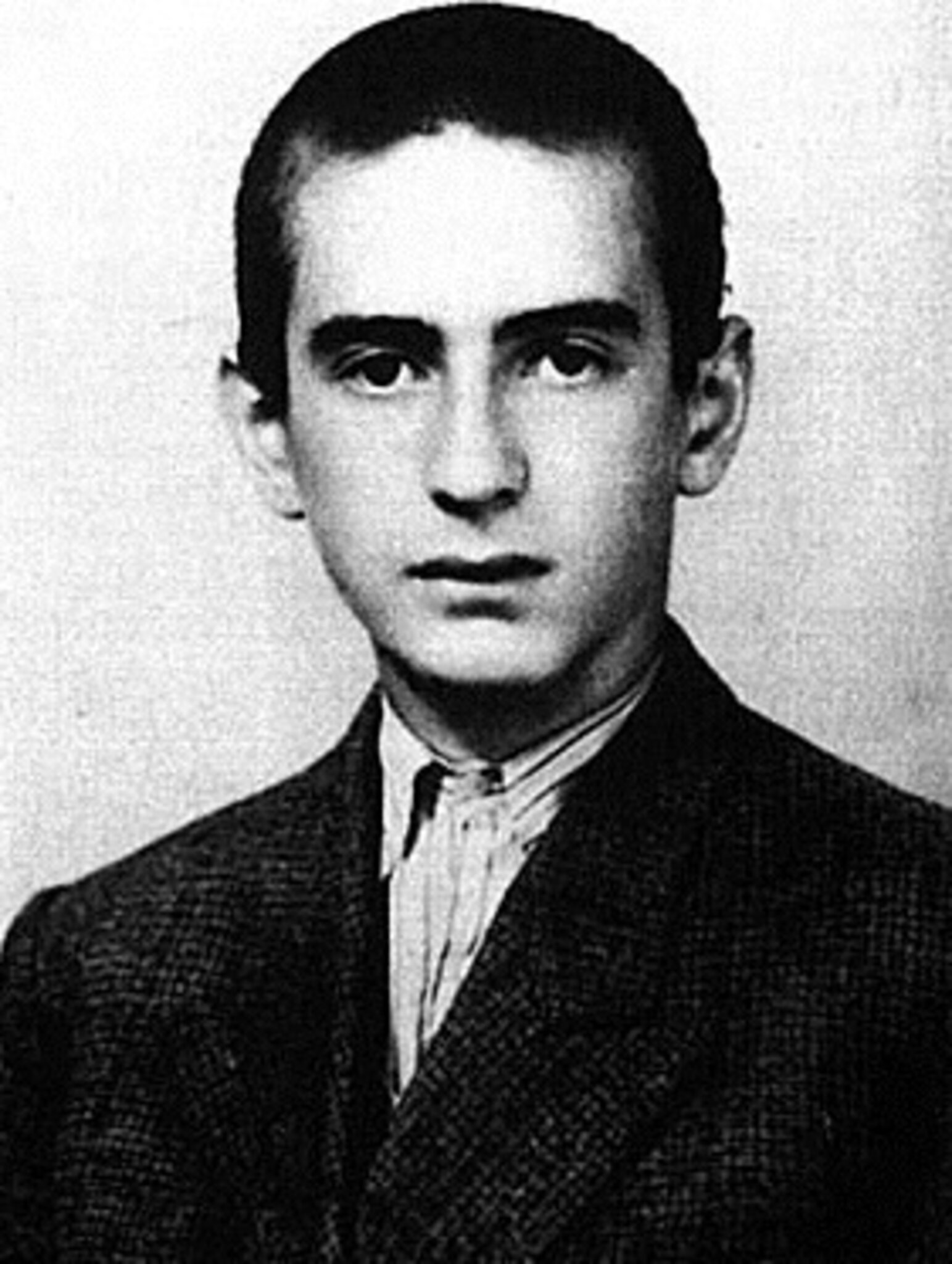

Elie Wiesel, aged 15, late 1943 or spring 1944.

Source: Chicago Public Library. © Elie Wiesel. CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Elie Wiesel – Other resources

Links to other sites

The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity

Elie Wiesel: First Person Singular from PBS, Public Broadcasting Service

The Academy of Achievement – Profile, Biography and Interview with Elie Wiesel

Elie Wiesel – Acceptance Speech

Elie Wiesel’s Acceptance Speech, on the occasion of the award of the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, December 10, 1986

It is with a profound sense of humility that I accept the honor you have chosen to bestow upon me. I know: your choice transcends me. This both frightens and pleases me.

It frightens me because I wonder: do I have the right to represent the multitudes who have perished? Do I have the right to accept this great honor on their behalf? … I do not. That would be presumptuous. No one may speak for the dead, no one may interpret their mutilated dreams and visions.

It pleases me because I may say that this honor belongs to all the survivors and their children, and through us, to the Jewish people with whose destiny I have always identified.

I remember: it happened yesterday or eternities ago. A young Jewish boy discovered the kingdom of night. I remember his bewilderment, I remember his anguish. It all happened so fast. The ghetto. The deportation. The sealed cattle car. The fiery altar upon which the history of our people and the future of mankind were meant to be sacrificed.

I remember: he asked his father: “Can this be true?” This is the twentieth century, not the Middle Ages. Who would allow such crimes to be committed? How could the world remain silent?

And now the boy is turning to me: “Tell me,” he asks. “What have you done with my future? What have you done with your life?”

And I tell him that I have tried. That I have tried to keep memory alive, that I have tried to fight those who would forget. Because if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices. We could not prevent their deaths the first time, but if we forget them they will be killed a second time. And this time, it will be our responsibility.

And then I explained to him how naive we were, that the world did know and remain silent. And that is why I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Wherever men or women are persecuted because of their race, religion, or political views, that place must – at that moment – become the center of the universe.

Of course, since I am a Jew profoundly rooted in my peoples’ memory and tradition, my first response is to Jewish fears, Jewish needs, Jewish crises. For I belong to a traumatized generation, one that experienced the abandonment and solitude of our people. It would be unnatural for me not to make Jewish priorities my own: Israel, Soviet Jewry, Jews in Arab lands … But there are others as important to me. Apartheid is, in my view, as abhorrent as anti-Semitism. To me, Andrei Sakharov‘s isolation is as much of a disgrace as Josef Biegun’s imprisonment. As is the denial of Solidarity and its leader Lech Wałęsa‘s right to dissent. And Nelson Mandela‘s interminable imprisonment.

There is so much injustice and suffering crying out for our attention: victims of hunger, of racism, and political persecution, writers and poets, prisoners in so many lands governed by the Left and by the Right. Human rights are being violated on every continent. More people are oppressed than free. And then, too, there are the Palestinians to whose plight I am sensitive but whose methods I deplore. Violence and terrorism are not the answer. Something must be done about their suffering, and soon. I trust Israel, for I have faith in the Jewish people. Let Israel be given a chance, let hatred and danger be removed from her horizons, and there will be peace in and around the Holy Land.

Yes, I have faith. Faith in God and even in His creation. Without it no action would be possible. And action is the only remedy to indifference: the most insidious danger of all. Isn’t this the meaning of Alfred Nobel’s legacy? Wasn’t his fear of war a shield against war?

There is much to be done, there is much that can be done. One person – a Raoul Wallenberg, an Albert Schweitzer, one person of integrity, can make a difference, a difference of life and death. As long as one dissident is in prison, our freedom will not be true. As long as one child is hungry, our lives will be filled with anguish and shame. What all these victims need above all is to know that they are not alone; that we are not forgetting them, that when their voices are stifled we shall lend them ours, that while their freedom depends on ours, the quality of our freedom depends on theirs.

This is what I say to the young Jewish boy wondering what I have done with his years. It is in his name that I speak to you and that I express to you my deepest gratitude. No one is as capable of gratitude as one who has emerged from the kingdom of night. We know that every moment is a moment of grace, every hour an offering; not to share them would mean to betray them. Our lives no longer belong to us alone; they belong to all those who need us desperately.

Thank you, Chairman Aarvik. Thank you, members of the Nobel Committee. Thank you, people of Norway, for declaring on this singular occasion that our survival has meaning for mankind.

Elie Wiesel – Nobel Symposia

At the Nobel Centennial Symposia, held on 7 December 2001 in Oslo, Norway, Elie Wiesel delivered this speech.

Elie Wiesel – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1986

Hope, despair and memory

A Hasidic legend tells us that the great Rabbi Baal-Shem-Tov, Master of the Good Name, also known as the Besht, undertook an urgent and perilous mission: to hasten the coming of the Messiah. The Jewish people, all humanity were suffering too much, beset by too many evils. They had to be saved, and swiftly. For having tried to meddle with history, the Besht was punished; banished along with his faithful servant to a distant island. In despair, the servant implored his master to exercise his mysterious powers in order to bring them both home. “Impossible”, the Besht replied. “My powers have been taken from me”. “Then, please, say a prayer, recite a litany, work a miracle”. “Impossible”, the Master replied, “I have forgotten everything”. They both fell to weeping.

Suddenly the Master turned to his servant and asked: “Remind me of a prayer – any prayer .” “If only I could”, said the servant. “I too have forgotten everything”. “Everything – absolutely everything?” “Yes, except – “Except what?” “Except the alphabet”. At that the Besht cried out joyfully: “Then what are you waiting for? Begin reciting the alphabet and I shall repeat after you…”. And together the two exiled men began to recite, at first in whispers, then more loudly: “Aleph, beth, gimel, daleth…”. And over again, each time more vigorously, more fervently; until, ultimately, the Besht regained his powers, having regained his memory.

I love this story, for it illustrates the messianic expectation -which remains my own. And the importance of friendship to man’s ability to transcend his condition. I love it most of all because it emphasizes the mystical power of memory. Without memory, our existence would be barren and opaque, like a prison cell into which no light penetrates; like a tomb which rejects the living. Memory saved the Besht, and if anything can, it is memory that will save humanity. For me, hope without memory is like memory without hope.

Just as man cannot live without dreams, he cannot live without hope. If dreams reflect the past, hope summons the future. Does this mean that our future can be built on a rejection of the past? Surely such a choice is not necessary. The two are not incompatible. The opposite of the past is not the future but the absence of future; the opposite of the future is not the past but the absence of past. The loss of one is equivalent to the sacrifice of the other.

A recollection. The time: After the war. The place: Paris. A young man struggles to readjust to life. His mother, his father, his small sister are gone. He is alone. On the verge of despair. And yet he does not give up. On the contrary, he strives to find a place among the living. He acquires a new language. He makes a few friends who, like himself, believe that the memory of evil will serve as a shield against evil; that the memory of death will serve as a shield against death.

This he must believe in order to go on. For he has just returned from a universe where God, betrayed by His creatures, covered His face in order not to see. Mankind, jewel of his creation, had succeeded in building an inverted Tower of Babel, reaching not toward heaven but toward an anti-heaven, there to create a parallel society, a new “creation” with its own princes and gods, laws and principles, jailers and prisoners. A world where the past no longer counted – no longer meant anything.

Stripped of possessions, all human ties severed, the prisoners found themselves in a social and cultural void. “Forget”, they were told, “Forget where you came from; forget who you were. Only the present matters”. But the present was only a blink of the Lord’s eye. The Almighty himself was a slaughterer: it was He who decided who would live and who would die; who would be tortured, and who would be rewarded. Night after night, seemingly endless processions vanished into the flames, lighting up the sky. Fear dominated the universe. Indeed this was another universe; the very laws of nature had been transformed. Children looked like old men, old men whimpered like children. Men and women from every corner of Europe were suddenly reduced to nameless and faceless creatures desperate for the same ration of bread or soup, dreading the same end. Even their silence was the same for it resounded with the memory of those who were gone. Life in this accursed universe was so distorted, so unnatural that a new species had evolved. Waking among the dead, one wondered if one was still alive.

And yet real despair only seized us later. Afterwards. As we emerged from the nightmare and began to search for meaning. All those doctors of law or medicine or theology, all those lovers of art and poetry, of Bach and Goethe, who coldly, deliberately ordered the massacres and participated in them. What did their metamorphosis signify? Could anything explain their loss of ethical, cultural and religious memory? How could we ever understand the passivity of the onlookers and – yes – the silence of the Allies? And question of questions: Where was God in all this? It seemed as impossible to conceive of Auschwitz with God as to conceive of Auschwitz without God. Therefore, everything had to be reassessed because everything had changed. With one stroke, mankind’s achievements seemed to have been erased. Was Auschwitz a consequence or an aberration of “civilization” ? All we know is that Auschwitz called that civilization into question as it called into question everything that had preceded Auschwitz. Scientific abstraction, social and economic contention, nationalism, xenophobia, religious fanaticism, racism, mass hysteria. All found their ultimate expression in Auschwitz.

The next question had to be, why go on? If memory continually brought us back to this, why build a home? Why bring children into a world in which God and man betrayed their trust in one another?

Of course we could try to forget the past. Why not? Is it not natural for a human being to repress what causes him pain, what causes him shame? Like the body, memory protects its wounds. When day breaks after a sleepless night, one’s ghosts must withdraw; the dead are ordered back to their graves. But for the first time in history, we could not bury our dead. We bear their graves within ourselves.

For us, forgetting was never an option.

Remembering is a noble and necessary act. The call of memory, the call to memory, reaches us from the very dawn of history. No commandment figures so frequently, so insistently, in the Bible. It is incumbent upon us to remember the good we have received, and the evil we have suffered. New Year’s Day, Rosh Hashana, is also called Yom Hazikaron, the day of memory. On that day, the day of universal judgment, man appeals to God to remember: our salvation depends on it. If God wishes to remember our suffering, all will be well; if He refuses, all will be lost. Thus, the rejection of memory becomes a divine curse, one that would doom us to repeat past disasters, past wars.

Nothing provokes so much horror and opposition within the Jewish tradition as war. Our abhorrence of war is reflected in the paucity of our literature of warfare. After all, God created the Torah to do away with iniquity, to do away with war1.Warriors fare poorly in the Talmud: Judas Maccabeus is not even mentioned; Bar-Kochba is cited, but negatively2. David, a great warrior and conqueror, is not permitted to build the Temple; it is his son Solomon, a man of peace, who constructs God’s dwelling place. Of course some wars may have been necessary or inevitable, but none was ever regarded as holy. For us, a holy war is a contradiction in terms. War dehumanizes, war diminishes, war debases all those who wage it. The Talmud says, “Talmidei hukhamim shemarbin shalom baolam” (It is the wise men who will bring about peace). Perhaps, because wise men remember best.

And yet it is surely human to forget, even to want to forget. The Ancients saw it as a divine gift. Indeed if memory helps us to survive, forgetting allows us to go on living. How could we go on with our daily lives, if we remained constantly aware of the dangers and ghosts surrounding us? The Talmud tells us that without the ability to forget, man would soon cease to learn. Without the ability to forget, man would live in a permanent, paralyzing fear of death. Only God and God alone can and must remember everything.

How are we to reconcile our supreme duty towards memory with the need to forget that is essential to life? No generation has had to confront this paradox with such urgency. The survivors wanted to communicate everything to the living: the victim’s solitude and sorrow, the tears of mothers driven to madness, the prayers of the doomed beneath a fiery sky.

They needed to tell the child who, in hiding with his mother, asked softly, very softly: “Can I cry now?” They needed to tell of the sick beggar who, in a sealed cattle-car, began to sing as an offering to his companions. And of the little girl who, hugging her grandmother, whispered: “Don’t be afraid, don’t be sorry to die… I’m not”. She was seven, that little girl who went to her death without fear, without regret.

Each one of us felt compelled to record every story, every encounter. Each one of us felt compelled to bear witness, Such were the wishes of the dying, the testament of the dead. Since the so-called civilized world had no use for their lives, then let it be inhabited by their deaths.

The great historian Shimon Dubnov served as our guide and inspiration. Until the moment of his death he said over and over again to his companions in the Riga ghetto: “Yidden, shreibt un fershreibt” (Jews, write it all down). His words were heeded. Overnight, countless victims become chroniclers and historians in the ghettos, even in the death camps. Even members of the Sonderkommandos, those inmates forced to burn their fellow inmates’ corpses before being burned in turn, left behind extraordinary documents. To testify became an obsession. They left us poems and letters, diaries and fragments of novels, some known throughout the world, others still unpublished.

After the war we reassured ourselves that it would be enough to relate a single night in Treblinka, to tell of the cruelty, the senselessness of murder, and the outrage born of indifference: it would be enough to find the right word and the propitious moment to say it, to shake humanity out of its indifference and keep the torturer from torturing ever again. We thought it would be enough to read the world a poem written by a child in the Theresienstadt ghetto to ensure that no child anywhere would ever again have to endure hunger or fear. It would be enough to describe a death-camp “Selection”, to prevent the human right to dignity from ever being violated again.

We thought it would be enough to tell of the tidal wave of hatred which broke over the Jewish people for men everywhere to decide once and for all to put an end to hatred of anyone who is “different” – whether black or white, Jew or Arab, Christian or Moslem – anyone whose orientation differs politically, philosophically, sexually. A naive undertaking? Of course. But not without a certain logic.

We tried. It was not easy. At first, because of the language; language failed us. We would have to invent a new vocabulary, for our own words were inadequate, anemic.

And then too, the people around us refused to listen; and even those who listened refused to believe; and even those who believed could not comprehend. Of course they could not. Nobody could. The experience of the camps defies comprehension.

Have we failed? I often think we have.

If someone had told us in 1945 that in our lifetime religious wars would rage on virtually every continent, that thousands of children would once again be dying of starvation, we would not have believed it. Or that racism and fanaticism would flourish once again, we would not have believed it. Nor would we have believed that there would be governments that would deprive a man like Lech Wałęsa of his freedom to travel merely because he dares to dissent. And he is not alone. Governments of the Right and of the Left go much further, subjecting those who dissent, writers, scientists, intellectuals, to torture and persecution. How to explain this defeat of memory?

How to explain any of it: the outrage of Apartheid which continues unabated. Racism itself is dreadful, but when it pretends to be legal, and therefore just, when a man like Nelson Mandela is imprisoned, it becomes even more repugnant. Without comparing Apartheid to Nazism and to its “final solution” – for that defies all comparison – one cannot help but assign the two systems, in their supposed legality, to the same camp. And the outrage of terrorism: of the hostages in Iran, the coldblooded massacre in the synagogue in Istanbul, the senseless deaths in the streets of Paris. Terrorism must be outlawed by all civilized nations – not explained or rationalized, but fought and eradicated. Nothing can, nothing will justify the murder of innocent people and helpless children. And the outrage of preventing men and women like Andrei Sakharov, Vladimir and Masha Slepak, Ida Nudel, Josef Biegun, Victor Brailowski, Zakhar Zonshein, and all the others known and unknown from leaving their country. And then there is Israel, which after two thousand years of exile and thirty-eight years of sovereignty still does not have peace. I would like to see this people, which is my own, able to establish the foundation for a constructive relationship with all its Arab neighbors, as it has done with Egypt. We must exert pressure on all those in power to come to terms.

And here we come back to memory. We must remember the suffering of my people, as we must remember that of the Ethiopians, the Cambodians, the boat people, Palestinians, the Mesquite Indians, the Argentinian “desaparecidos” – the list seems endless.

Let us remember Job who, having lost everything – his children, his friends, his possessions, and even his argument with God – still found the strength to begin again, to rebuild his life. Job was determined not to repudiate the creation, however imperfect, that God had entrusted to him.

Job, our ancestor. Job, our contemporary. His ordeal concerns all humanity. Did he ever lose his faith? If so, he rediscovered it within his rebellion. He demonstrated that faith is essential to rebellion, and that hope is possible beyond despair. The source of his hope was memory, as it must be ours. Because I remember, I despair. Because I remember, I have the duty to reject despair. I remember the killers, I remember the victims, even as I struggle to invent a thousand and one reasons to hope.

There may be times when we are powerless to prevent injustice, but there must never be a time when we fail to protest. The Talmud tells us that by saving a single human being, man can save the world. We may be powerless to open all the jails and free all the prisoners, but by declaring our solidarity with one prisoner, we indict all jailers. None of us is in a position to eliminate war, but it is our obligation to denounce it and expose it in all its hideousness. War leaves no victors, only victims. I began with the story of the Besht. And, like the Besht, mankind needs to remember more than ever. Mankind needs peace more than ever, for our entire planet, threatened by nuclear war, is in danger of total destruction. A destruction only man can provoke, only man can prevent. Mankind must remember that peace is not God’s gift to his creatures, it is our gift to each other.

1. The Torah is the Hebrew name for the first five books of the Scriptures, in which God hands down the tablets of the Law to Moses on Mt. Sinai. In contradistinction to the Law of Moses, the Written Law, the Talmud is the vast compilation of the Oral Law, including rabbinical commentaries and elaborations.

2. Judas Maccabeus led the struggle against Antiochus IV of Syria. He defeated a Syrian expedition and reconsecrated the Temple in Jerusalem (c. 165 B.C.). Simon Bar-Kochba (or Kokba) was the leader of the Hebrew revolt against the Romans, 132-135 A.D.

Elie Wiesel – Facts

Elie Wiesel – Biographical

Elie Wiesel was born in 1928 in the town of Sighet, now part of Romania. During World War II, he, with his family and other Jews from the area, were deported to the German concentration and extermination camps, where his parents and little sister perished. Wiesel and his two older sisters survived. Liberated from Buchenwald in 1945 by advancing Allied troops, he was taken to Paris where he studied at the Sorbonne and worked as a journalist.

In 1958, he published his first book, La Nuit, a memoir of his experiences in the concentration camps. He has since authored nearly thirty1 books some of which use these events as their basic material. In his many lectures, Wiesel has concerned himself with the situation of the Jews and other groups who have suffered persecution and death because of their religion, race or national origin. He has been outspoken on the plight of Soviet Jewry, on Ethiopian Jewry and on behalf of the State of Israel today2.

Wiesel has made his home in New York City, and is now a United States citizen. He has been a visiting scholar at Yale University, a Distinguished Professor of Judaic Studies at the City College of New York, and since 1976 has been Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Boston University where he teaches “Literature of Memory.” Chairman of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council from 1980 – 1986, Wiesel serves on numerous boards of trustees and advisors.

1. forty (updated by Laureate – August 99)

2. and of the victims in Bosnia and Kosovo (updated by Laureate – August 99)

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

| Selected Bibliography |

| By Elie Wiesel |

| Against Silence: The Voice and Vision of Elie Wiesel. Ed., Irving Abrahamson. 3 vols. New York: Schocken, 1984. |

| All Rivers Run to the Sea: Memoirs. New York: Knopf, 1995. |

| From the Kingdom of Silence. New York: Summit, 1984. (Reminiscences, including text of Nobel speeches.) |

| The Night Trilogy: Night, Dawn, The Accident. New York: Hill & Wang, 1987. (Autobiographical novels.) |

| Other Sources |

| Brown, Robert McAfee, Elie Wiesel: Messenger to all Humanity. South Bend, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984. |

| Fine, Ellen S., Legacy of Night: The Literary University of Elie Wiesel. Albany, NY State University of New York Press, 1982. |

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Elie Wiesel died on 2 July 2016.

Elie Wiesel – Interview

Interview with Elie Wiesel, December 10, 2004. Interviewer is Professor Georg Klein.

Elie Wiesel talks about his perspectives on the world after World War II, recollections of his time in concentration camp (5:41), the indifference of the world (12:42), antisemitism (16:42), the importance of education (22:26) and that the tragedy of the Holocaust could have been avoided (24:31).

Interview transcript

Your prize is the only peace prize, certainly, that has been explicitly given concerning genocide and the need of remembrance. There have been some prizes in literature, Nelly Sachs, Imre Kertész, dealing with holocaust literature where I think in peace prize you are the only one and I wonder what your perspective is today, after some more genocides, after the rise of Neo Nazism over the world. Has your perspective changed as you look back over a large piece of history?

Elie Wiesel: Georg my friend, you know how many reasons we have to be desperate and despairing, the world is not learning anything. We have seen that. You and I went through certain experiences – if anyone had told us in 1945 that there are certain battles we’ll have to fight again we wouldn’t have believed it. Racism, anti-Semitism, starvation of children and, who would have believed that? At least I was convinced then, naively, that at least something happened in history that, because of myself, certain things cannot happen again. I was convinced that hatred among nations and among people perished in Auschwitz. It didn’t. The victims died but the haters are still here. New ones. And so often I say to myself “Really, what are we doing on this planet?” We are passing the message as well as we can, communicating our fears, our hopes … Day in day out, week after week and year after year, people kill each other.

I’m a biologist and I wonder whether you would agree with me that civilisation and humanism are a thin veneer over a much deeper layer of primitive emotions?

Elie Wiesel: Well, you speak as a scientist, I’d rather speak as a student of philosophy. Philosophically it makes no sense, absolutely makes no sense. Why should people inherit evil things when their memories could contain and should invoke good things? It’s true that the veneer’s of course /—/. The darkest days in my life after the war, after the war, was when I discovered that the … most of the members and commanders of the Einsatz group that were doing the killings, not even in gas chambers, but killing with machine guns, had college degrees from German universities and PhD’s and MD’s. Couldn’t believe it. What do you mean? I thought that culture and education are the shield. An educated person cannot do certain things and, and be educated, you cannot, and there they were, killing children day after day and what happened to them?

Doesn’t that mean that the basic theories are not correct?

I think that human beings are capable of the worst things possible …

I think that human beings are capable of the worst things possible …Elie Wiesel: Georg, our experiences really force us to recall many certainties into question. But whatever we thought was certain is no longer certain, and therefore in science probably certain things must be correct, but in human behaviour I am not so sure. I think that human beings are capable of the worst things possible and they show that there were times, and there probably are times, that it is human to be inhuman.

Oh, yes certainly, I mean all the inhuman totalitarian systems have their own “ethics”, meaning that it is not only good to kill, but it is justified and more to kill, I mean that was the Nazi philosophy.

Elie Wiesel: And in different way, I never compared Nazis into communism, but communism was the same thing, the end justifies the means. Whatever the means.

But don’t you think that there are two things here, one at the individual level that is a limbic system, the lower republics in the loose federation of the brain, ready to take over as soon as we are stressed, and at the collective system there is a conformism.

Elie Wiesel: It’s easier to be conformist naturally; it’s easier except for those who don’t like conformism. For us it’s not easy to be conformist, I cannot stand to be conformist, I don’t accept what it is, I like to say no. If I see an injustice I scream.

So isn’t that the interesting thing to study, just that non-conformism, why.

Elie Wiesel: Why? What is literature, what is art, what is music, what is even science? To say no, we say no.

You know Imre Kertész book, Being without a Fate … have you read it?

Elie Wiesel: I know of this book, yes.

Have you read it?

Elie Wiesel: I have read all of his works. In French, I have read his books in French.

In French? Because in that particular book, seeing Auschwitz through the eyes of a 14 year old, the amazing thing to me when I first read it, long before knowing him, was that when he sees and describes the most terrible things, things I can’t mention, he says “Well, this was to be expected, this is only natural, it could not be any other way” and what he’s surprised by is goodness. Goodness is what he didn’t expect. So what is the difference between his and your background?

Elie Wiesel: The same. I was 15, not 14, when I was inside there, 15, and for me both were actually a surprise.

It was a surprise?

Elie Wiesel: Both was a surprise, but naturally when I saw, and when I remember those faces of people who were good I saw that. I saw a father who gave his bread to his son and his son gave back the bread to his father. That, to me, was such a defeat of the enemies, will of the enemies, theories of the enemies, aspirations, here.

But these were rare, right?

Elie Wiesel: Yes. Still I believe that Hanna Arendt, she was wrong when she tried to say that we are all actually capable of this, it’s not true. I think it’s not true. There are certain things human beings are not capable of. I mean people, even normal human beings. You have to do certain things in order to become what the enemy was and I didn’t accept her philosophical outlook on that. Nevertheless I feel that to me the greatest astonishment was the very first day, the very first hour.

Of deportation …

Elie Wiesel: … of deportation, and I came to a place that I realised that is a creation parallel to creation, and the universe. Parallel to the universe and in that universe people come to kill, others come to die and they have their own language, their own philosophy, their own theology, their princes, their beggars, their moralists, everything. That for me was a surprise. Wait a second, I thought that God’s world is only one world and here I see another world parallel to that world.

You were surprised both by the evil and the good, Kertész is only surprised by the good, could it be that that difference, which I think is interesting, is that you are a religious person whereas he’s not?

Elie Wiesel: Probably, yes. I had my religious crisis after the war, not during the war. After the war.

Were you religious at that time?

Elie Wiesel: Yes, I come from a very religious background, you know, Máramarossziget, very religious. And actually I remained in it. All my anger I describe in my quarrels with God in Auschwitz, but you know I used to pray every day.

But how do you solve that problem psychologically?

Elie Wiesel: I don’t.

But you can live with it and still remain religious?

I didn’t divorce God, but I’m quarrelling and arguing and questioning …

I didn’t divorce God, but I’m quarrelling and arguing and questioning …Elie Wiesel: My faith is a wounded faith, but it’s not without faith. My life is not without faith. I didn’t divorce God, but I’m quarrelling and arguing and questioning, it’s a wounded faith.

How do you see the other genocides that are going on in the world all the time? Is it part of the same thing or is the Holocaust unique?

Elie Wiesel: I think the Holocaust … I make a difference between genocide and Holocaust. Holocaust was mainly Jewish, that was the only people, to the last Jew, sentenced to die for one reason, for being Jewish, that’s all. In other centuries you could have escaped death by conversion, by running away, not here. There’s no way, I mean, and therefore that is, I call it wrongly, there are now words, Holocaust is the wrong word too.

Yes absolutely.

Elie Wiesel: It’s the wrong word. That’s why usually I don’t mention it any more, if I want to say something about that period I say Auschwitz or something, but it’s not. Genocide is something else. Genocide has been actually codified by the United Nations. It’s the intent of killing, the intent of killing people, a community in this culture so forth, but no other people has been really interested. Rwanda, God knows I was involved in trying to save the Rwandan people and Sudan now. It’s a mass murder. Mass murder is a terrifying word. We don’t have to go further than that. Cambodia came close to, but what was it, Cambodians killing Cambodians after all. So therefore I think we should be very careful with vocabulary.

I wonder whether you would agree with me, probably not. Two things. That killing the Jews, all the Jews to the very last one, even the converted to Jews, is a logical consequence and I suggest that’s logical of the paranoid type of anti-Semitism, the one that really believes firmly and honestly, I think, and like Hitler probably believed, that the Jews are the cancer of the world, and essentially believed the accusations which I put down in the Falsarium, the Protocols of the Wise of Zion. If you entertain that notion and you want to pull it out to its logical conclusion like Germans so often do and if you are forced in addition to that with large numbers of Jews concentrated that you don’t know what to do with them, that killing them is a logical conclusion.

Elie Wiesel: Killing some Jews but not all Jews. But again, a Jew who converted, who assimilated, was, at least in some periods, safe. Hitler in the beginning did not want to kill all the Jews but he wanted us to have a Germany free of Jews. If America had allowed Jews to come in, the British had accepted Jews from Palestine, they were safe. But Hitler needed, he didn’t want to kill Jews, he wanted to expel German Jews, and therefore it’s not entirely corroborating your theory.

And that brings me to the derivative question that you speak about: America, the silence of the world and the total indifference of the world. Actually in Hungary, I think we probably both experienced, to me the great surprise was a total indifference of the majority of the Hungarians about what was going to happen to us and that I would not have expected. And we were part of the same culture, we spoke the same language, we loved the language and the literature at least, some of our fathers had been great patriots fighting the wars, therefore one would have expected a little more sympathy, a little more help. There was some help but that to me the greatest surprise is not the Nazis, not the killers, and not the Arrow Cross, but the indifference of the vast majority. If you compare to say to the Danish.

Elie Wiesel: You know I wrote my first book, I published it in 1955, it was in Jiddish and it was called And The World Was Silent.

Oh yes, I know that, yes..

Elie Wiesel: 1955. But then it became Night, La Nuit, or Night.

Night, yes.

Elie Wiesel: But the world, how can a world be silent, that was my shock really and I say like I describe it in Night, to my father, it’s impossible, the world wouldn’t be silent, but the world was silent.

And do you have an answer to that now?

Elie Wiesel: But as to Hungary I’ll come to that. You know I’m sure you … you know it better than I … We lived in our little town, even under the Romanian regime we spoke Hungarian at home and my parents still remember the/- – -/ Hungarians and before 1914 or so and they loved Hungary. They loved it. They knew more about Hungarian literature than about Romanian literature, Petőfi. At home we spoke … And when the Hungarians came in, we felt good, we went to greet them /- – -/ Hungary we have so much in common and then I remember my father in the early forties did everything possible to get to prove, proof that we were Hungarian citizens and then we got the papers, I never left them, they were always in my pocket, and then in 1944, May, when the deportation began we came to the Synagogue, all the Jews were assembled and we gave the papers, thinking now we would be protected by a Hungarian Lieutenant. He didn’t even look at them, just threw them up into the waste basket. That to me was a very important moment.

So what did that moment lead to, how did your feelings change radically and forever towards Hungarians?

Elie Wiesel: Then I thought forever. I wrote in Night, I said that at that time I began hating Hungarians.

You know that there is a statue of you, a bust, on the corridor of the first floor of the Hungarian Academy of Science, did you know that? And that’s where all the Hungarian Nobel Laureates are put on display, and they will gather everyone they can for instance about Imre, he was a Hungarian writer, but also Hershko, yes, yes, they announced him as a Hungarian Laureate, even the Swedish people /- – -/ and said Hungarian Laureate. Whereas of course what all the Hungarians wanted to do, was to kill him and his family. So how do you feel about that?

I did everything I could in my life to be immune to hatred, because hatred is a cancer.

I did everything I could in my life to be immune to hatred, because hatred is a cancer.Elie Wiesel: I had to be honest with myself and that I felt hatred then, but as children say “I hate you”, it’s not really hate, you know, it’s anger but I wrote it because I felt it, but in truth I’m against hatred. I did everything I could in my life to be immune to hatred, because hatred is a cancer.

Well, let’s turn it around then and I’m sure you know the film Shoa by Lanzmann, yes. You remember that wonderful idyllic scene in front of the church on a beautiful Sunday morning in the spring and there are girls dressed in white in the procession, and there are these wonderful old peasant women who could be anybody’s grandmother and they’re so full of beauty and love, and then Lanzmann let interpreters and asks questions: Is this the church where the Jews have been, and how many and was there any toilet? And he gets the answers and of course it immediately appears that these were actually terrible conditions, and then he says: Is it true that this church was put on fire with all the Jews in it? Yes, yes and then suddenly you see the camera focuses on one face, it’s one of these beautiful old women, and suddenly it’s distorted in an ugly horrible grimace and she starts shouting: It’s right, they killed Christ! and then suddenly they’re all shouting. So would you agree with me that one important source of anti-Semitism that’s surviving to /- – -/ is in the evangelia ?

Elie Wiesel: It is. It is, of course I agree, but then you must also remember that John XXIII was a very great pope and he’s the one who actually corrected the liturgy. He did so because of his friend Jules Isaac, a French Jewish historian who was a friend of John Paul, of John 23rd, and he convinced him and he changed the liturgy, no more Jew, the perfidious Jew and so forth and now, and don’t speak any more of the Jews killing Christ. Things have changed.

Officially yes.

Elie Wiesel: Officially, but it has, look that’s, I, the Jew that’s religious, can tell you but I feel now never before have the relations between Jews and Christians been as good.

That’s interesting.

Elie Wiesel: Never before.

You feel relatively good about it?

Elie Wiesel: Not enough, but on certain levels. The Pope going to Jerusalem, the Pope recognising the State of Israel, the Pope going to the wall, to Yad Vashem, organising a concert for the Holocaust in the Vatican, going to the synagogue in Vatican, and that happens in Protestant service as well. That doesn’t mean that anti-Semitism disappear, but it is on certain level that Jews all the time, or with Christians, Catholics, Protestants, Jews, meeting all the time, studying together, signing petitions for all kinds of causes. So on the other hand it’s true, that the poison of the church which has existed in certain, of course, evangelical writings is still there, but it’s better than ever before.

I am glad you say that. I once had a correspondence with one of the Editors in Chief of one of the daily papers here in Stockholm because some Jews here in the city asked me to go along with them, to him, because this was a time when there was very much anti Israeli publicity, 20 years ago. There’s always a lot, but this was more than usual, and some of the publicity was different in gliding from anti-Zionism to anti-Semitism. And we went up to see him and we had a long discussion which was very fruitful, but then the English correspondence and I wrote to him that I believe that every child who learned the ascent of the Evangelia at the age of six or seven may have an anti-Semitic bias without knowing it, and he, a very honest man, wrote back to me saying “I don’t believe that what you are saying is true, but I cannot exclude it and that worries me”, which is very good.

Elie Wiesel: It is true actually, it depends who is teaching. Today again the teacher is the important thing, but on the other hand anti-Semitism is growing today. No doubt about it. All over the world, especially in Europe, and it’s true they begin with anti-Israeli attitudes and then it’s so strong that it runs over and becomes anti-Semitic.

But do you agree that maybe an unholy alliance between the anti-Semitism of the left, the old type Christian anti-Semitism and then the new Muslim or let’s say Jihad type of anti-Semitism.

Elie Wiesel: There is a coalition.

There is a coalition, yes.

Elie Wiesel: There is a coalition of anti-Semitism today, the extreme left, the extreme right and in the middle the huge corpus of Islam. I’m worried, I go around, you know, with a very heavy heart.

And do you also go to Muslim countries?

Elie Wiesel: I have been but not … Before 9/11 I had contacts with Palestinians, Arabs and with Muslims, since then they are afraid. I’m organising now something, I’m organising for next year … You think about Islam and so forth, many Islamic leaders and so forth, because I, you know, I’ve organised for the last 18 years, since I got the Nobel Prize actually, Anatomy of Hate Conferences all over the world, what is hate. Didn’t help but at least they explored it.

Well I think it is extremely important and just like during the Cold War, the Pugwash Conferences,/- – -/ , the Spirit of …

Elie Wiesel: Exactly.

And do you find that you can talk across the barriers of hate?

Elie Wiesel: I think we can, because there’s only one, I don’t know the real answer, my answer to anything which is essentially human relations is education. Whatever the answer is, education must be its major component and if you try to educate with generosity not with triumphalism I think sometimes it works, especially young people, that’s why I teach, I’ve been teaching all my life.

As to the youth culture today … Sorry I’m sort of lifting into a bit wider questions, but how do you see, are you pessimistic about it and of all this junk that inundates the young? The disappearance of the importance of learning, of education, it seems alright in some places /- – -/.

Elie Wiesel: I’ll tell you … I’m a privileged person, I feel privileged because of who I am. I write books, I write novels, I write essays and I teach and I go from university to university. I’m one of the old, but I still go around, but I only see those who are not like that, I don’t see the junk youth. I only meet students, and even those who are not formally at the university, if they come to listen to me, they come to read me, it means they are not junk students.

They are selected, of course …

Elie Wiesel: Exactly, self selected. But I feel therefore I don’t know, I think the young people are the contrary. Do you know when I began teaching, was 35 years ago, you hardly could find a university in America or a college where they would teach either Jewish studies or Holocaust studies. Today there isn’t a university where they don’t have special courses, hundreds and hundreds of universities, young people today want to know more than their elders did, much more, and therefore I am very optimistic about young people.

What do you tell them, may I ask, when they ask that ever returning question “We don’t understand how this could have happened, this is impossible to understand”. Do you say that it is possible to understand?

Elie Wiesel: No.

No you don’t say that?

Elie Wiesel: In truth I don’t think it’s possible. I agree with them. Georg, that tragedy which to me was the worst, the cruellest in the court of history could have been avoided. Why wasn’t it?

Could it had been avoided in any other way than by stopping Hitler?

Elie Wiesel: By stopping Hitler. By speaking up. I’ve worked with five Presidents in America, all of them I ask the same question always: Why didn’t the American allies bomb the railways going to Auschwitz?

Yes, I wanted to ask you that question. Did you get an answer?

Elie Wiesel: No. There’s no answer. I said “What do you mean, at that time they were bombing factories …”

Yes, but the President, the later Presidents, they probably wouldn’t know …

Elie Wiesel: Naturally I only … I began with Carter and Reagan and Clinton, the father, and Bush the father and Bush the son. I asked every President, why didn’t at least symbolically … so the Germans would have known that the world cares. It would have taken a few days to repair, that time there were 10-12,000 Hungarian Jews every day, every night, you know that, every day 10-12,000 people were gassed. It could have been avoided in the thirties …

So they couldn’t answer you? Did you ask the British?

Elie Wiesel: I asked a British General, but it was before his time, but I asked the American Secretaries of Defence, I asked American Generals, I asked Presidents. After all, there is no answer. They said, a few of them said they didn’t want to divert from /- – -/ Come on, what a few bombs, at that time they were having hundreds and hundreds of thousands of aircrafts bombing. I remember when they flew over Auschwitz we were hoping, we were praying for them to bomb Auschwitz and die, at least die in the bomb. And the first time it came to me, President Carter wanted to appoint with the Chairman of the President’s Commission on the Holocaust but I didn’t want it, I said to President “I am a teacher and I’m a writer, I’m not a …”, but he was very good and he quoted my own words to me, and he said “I knew you were coming to the White House, I asked the CIA Director, the admiral Stan Turner, what did you know about the place where Elie was?” So he had a folder with pictures on his desk in the Oval Office, and this is his answer; this were the pictures taken by American aircrafts and usually when they were bombing they were taking pictures, and at times they forgot to close the camera flying over Auschwitz and these were the pictures, and so I was, I became a guide to the President of the United States.

Did you never, did he never analyse it?

Elie Wiesel: I asked him, what would you have done, what would you have done?

There is a major new book about Eichmann, I didn’t read, I just saw the review in the New York Review of Books this week and apparently the book is a very good study, but the word that comes back about Eichmann all the time is “contingency” and depending on really unimportant things this book of contingency that influences decisions in this direction or that direction, or the absence of decisions. Could it be just that? I mean chaos theory.

… they could have saved so many people and they didn’t.

… they could have saved so many people and they didn’t.Elie Wiesel: No, not chaos, no, no, no. That was not chaos. They simply decided that it was not a priority. The American and the British armies liberated camps, there wasn’t a single order of the day: Let’s go and liberate the camp. They stumbled upon the camps. Same thing with the Russians, I asked the Colonel who liberated Auschwitz, they didn’t, there wasn’t a priority. But I feel that that was a mistake, it was a sin because they could have saved so many people and they didn’t.

The last question, do you know, or know of Rudolf Vrba.

Elie Wiesel: Very well.

Have you met him?

Elie Wiesel: No I was in touch with him, I read his book.

Yes you wrote about him, that he’s a genuine hero.

Elie Wiesel: Absolutely, to me he is a hero. He and his friend who escaped from Auschwitz and saved Hungarian Jews.

So he, his book was first called I Cannot Forgive and then he changed it into I Escaped from Auschwitz. He is, I think, quite of the same opinion as you are, although he’s more bitter I think about the Jewish leadership.

Elie Wiesel: He is and I understand it because he tried. He said, what did he say? He said we were, we saw all of a sudden barracks being built, gas chambers, we knew the only large community still alive is Hungary, that’s why they wanted to escape, to warn and he said: We came to warn and they didn’t listen. And in my memoir I described this because I didn’t understand the real life in Auschwitz, the Commander that received us: Why did you come, why did you come? We wanted to come, and the question was: Look we warned you, why did you come nevertheless?

But I think Vrba overestimates one thing and I keep telling him I am your guinea pig because I can tell you that your theory I have tested in life, namely my boss whom I worked for at the Jewish community, long time gone, a Rabbi, he showed me the report of Vrba and Wetzler during the first days of May in 1944.

Elie Wiesel: He did show it to you?

Yes. That’s why I escaped, that’s why I went underground, he showed it to me in May …

Elie Wiesel: You never told me.

Yes I’ve written about it, but maybe it’s not translated.

Elie Wiesel: I didn’t see it, no.

Yes I will send you what I have about it, I have now an essay on it and also on Vrba and my contacts with Vrba. Because what happened was that he showed me the report, it was a typewritten report, a carbon copy, and I saw one copy like that at the Wallenberg exhibition recently, it might have been the same copy. They took me, they made a film about Wallenberg, they took me to the same room where I have read this report, it’s still the same small room in the kibbutz house and I felt again exactly the same feeling I had then, namely a mixture of nausea and intellectual satisfaction. I knew it was true. It is written with such scientific precision but I was then allowed to go and tell my closest friends, my relatives and so I went straight to my uncle, living across the street, he was my father substitute, my father died when I was one, and showed it to him.

Now, he was a rheumatologist, an educated man, he was really like a father to me and he liked me very much, he loved me very much, at this time the only time in my life he got so mad that he almost hit me in the face and he said: Have you gone crazy to believe this? And then I went on and on and told other people, whoever it was, middle aged or had possessions, had family, they said this cannot be true. Young people like myself with no dependence, they believed it and they went underground like myself. I think that the idea of a publication of this would have led to something major, I don’t think that’s true.

Elie Wiesel: I think if anyone had called my father from Budapest and said: Look, this is the report, I think he would have gone into hiding not only alone, I think, yeah. It could have saved many people.

I’m sure that could have been the case in many places, but perhaps not …

Elie Wiesel: We come actually to the question of words, what do words mean, we’re not the carriers of truth, we’re not the carriers of something else, and as a writer … I have that problem day after day.

But isn’t it also dependent on the beholder?

Elie Wiesel: Nevertheless, we are led to believe that true words can communicate more than truth, they communicate what life is all about, that it’s threatened, when it’s threatened, when it’s in danger, then it becomes a curse or a blessing. We are led to believe otherwise, we are believe the people of the book after all, and will call us later Mohammed, he gave us that name. People of the book, and we are people of the word, of language.

Yes but the evolution of language is like the evolution of the poison of the snake, or the claws of the tiger, it can be an instrument of truth, it can be an instrument of lies.

Elie Wiesel: And who are we to say who is what and what is what? Look, Nietzsche said something marvellous, he said “Madness is not a consequence of uncertainty but of certainty”, and this is fanaticism and these words the fanatics use words and we use words, the same words, they are not the same words.

Amos Oz said once that he is qualified to become a Professor of comparative fanaticism because he was living in the midst of all the difference …

Elie Wiesel: Fanaticism is the greatest threat today. Literally, the 21st century just began and it’s already threatened by fanatics, and we have fanatics in every religion, including mine and yours, unfortunately and what can we do against them? Words nothing else, I’m against violence but only words.

And Elie, I think your words carry us very far.

Elie Wiesel: Oh, I try to.

And I hope you will continue in the same spirit.

Elie Wiesel: Thank you, thank you.

Thank you very much.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Elie Wiesel – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of Elie Wiesel receiving his Nobel Peace Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony at the Oslo City Hall in Norway, 10 December 1986.