Chiral objects, like left and right hands, cannot be superimposed on its mirror image. Find other ‘chiral’ objects in this game.

2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry: One-minute crash course

What is a MOF?

Did you know there are materials that can capture water from desert air?

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2025 recognises the development of materials with completely new features. The chemistry laureates have created porous metal–organic frameworks (abbreviated as MOFs). These have large cavities that other molecules can move in and out of. MOFs can be used to, for example, capture carbon dioxide and harvest water from the desert air.

Watch our one-minute crash course to discover the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Learn more

Text for students about the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Press release for the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Popular information about the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Interview with Olof Ramström, member of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, 6 minutes (YouTube)

All 2025 crash courses

-

Physics

-

Chemistry

What is a MOF?

-

Physiology or Medicine

The immune system’s security guards

-

Literature

The author László Krasznahorkai

-

-

Economic sciences

How to sustain economic growth

The 2025 chemistry prize – MOFs – molecular structures

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2025 recognises the development of materials with completely new features. The laureates have created porous metal-organic frameworks (abbreviated as MOFs). These have large cavities that other molecules, such as gases, can move in and out of.

Metal ions + organic molecules become networks (MOF)

Two concepts that are key to understanding the laureates’ discoveries are metal ions and organic molecules.

A metal is an element with a set structure. This means that the atoms are located in certain positions. Metals are characterised by having a metallic sheen and are often good conductors of electricity and heat. They exist in nature and are often found in minerals. A metal ion is a metal atom that has lost one or more electrons and thus has a positive charge.

Organic molecules are chemical compounds that make up all living organisms. They always contain carbon atoms and frequently also hydrogen atoms.

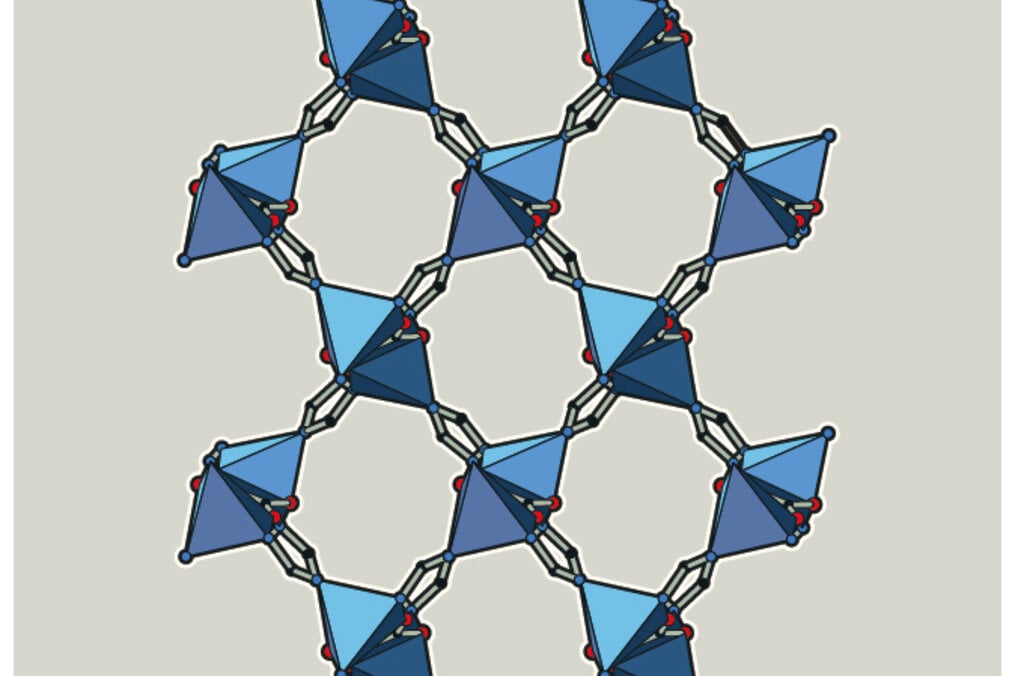

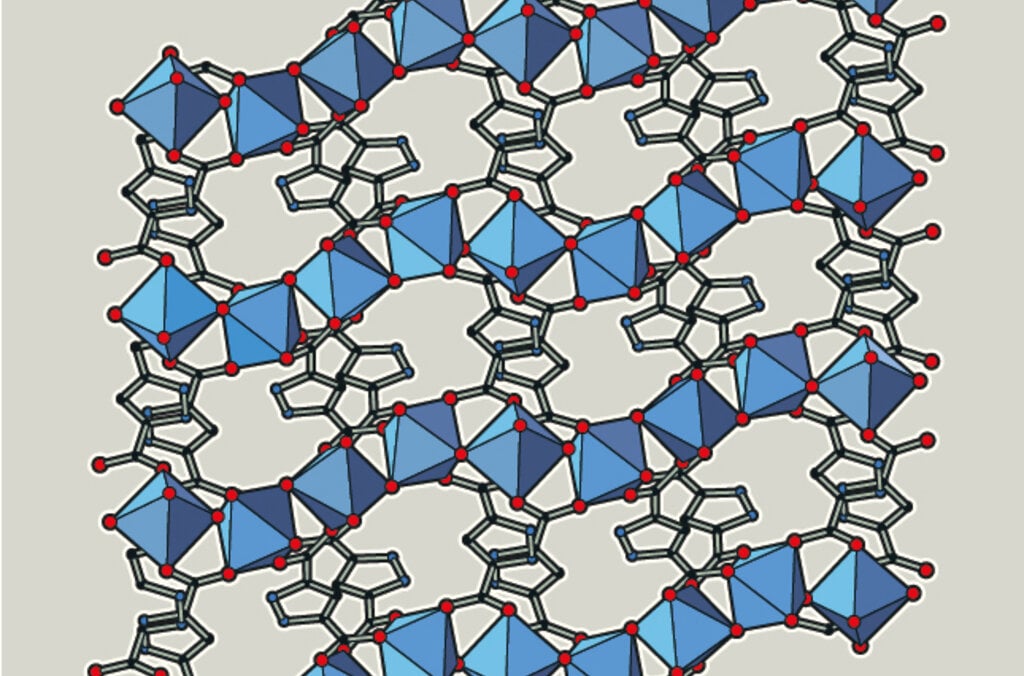

The chemistry laureates have created a completely new material, MOF, which is made up of metal ions and organic molecules. The metal ions function as cornerstones and are joined together with the organic molecules to become a three-dimensional network.

From idea to stable structures

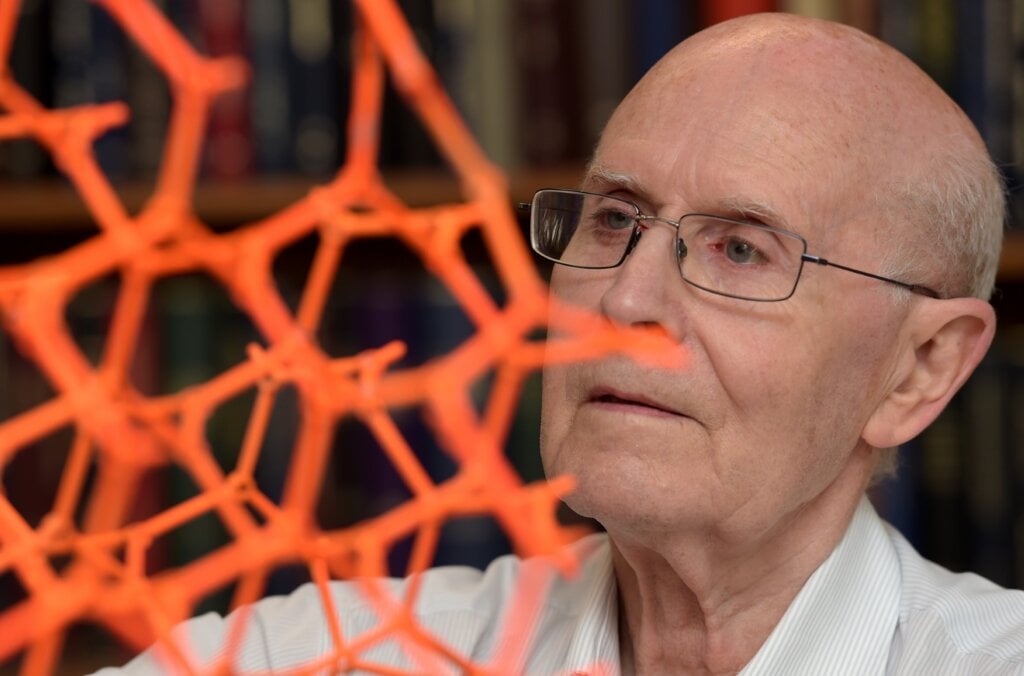

The history of the 2025 chemistry prize begins in Australia already in 1974. While the chemistry teacher Richard Robson was preparing a chemistry lesson, he got an idea. What if it was possible to design new types of molecular structures?

Ten years later, he decided to test his idea, and a couple of years later, he managed to build a well-ordered airy crystal by using copper ions. The first metal-organic framework had been created. This framework was unstable and would easily fall apart, but Robson predicted that the material would be useful in the future.

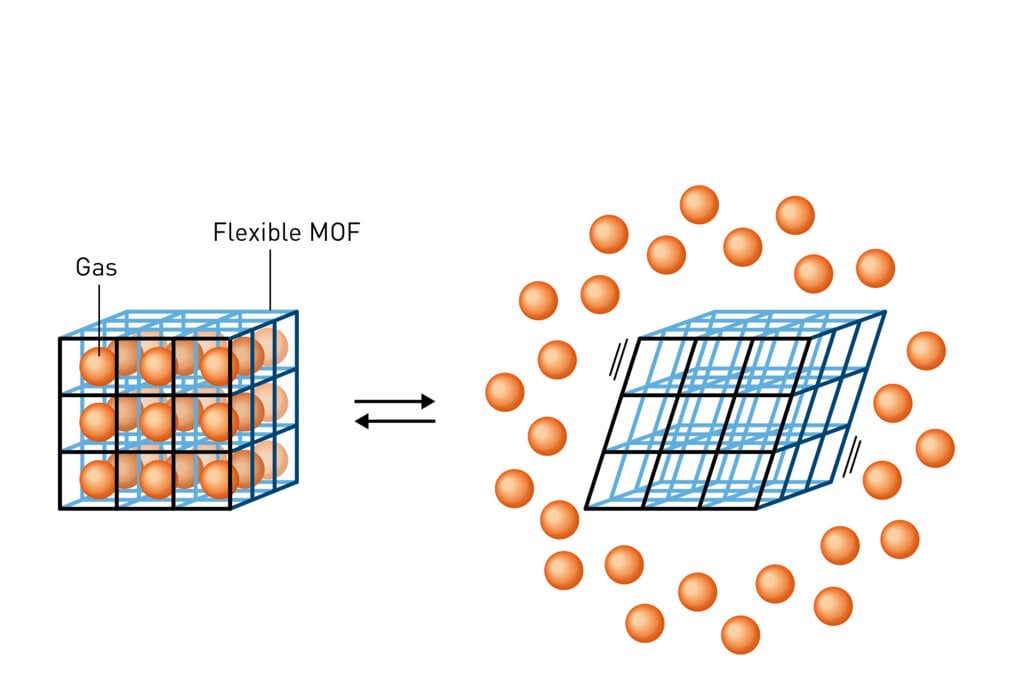

The other two laureates later laid a solid foundation for the new molecular structures, and Susumu Kitagawa explored the possibilities of creating hollow structures. The final breakthrough came at the end of the 1990s. He managed to create stable structures where the cavities could be filled with gases, which could then be released.

MOFs that hide huge surfaces in their cavities

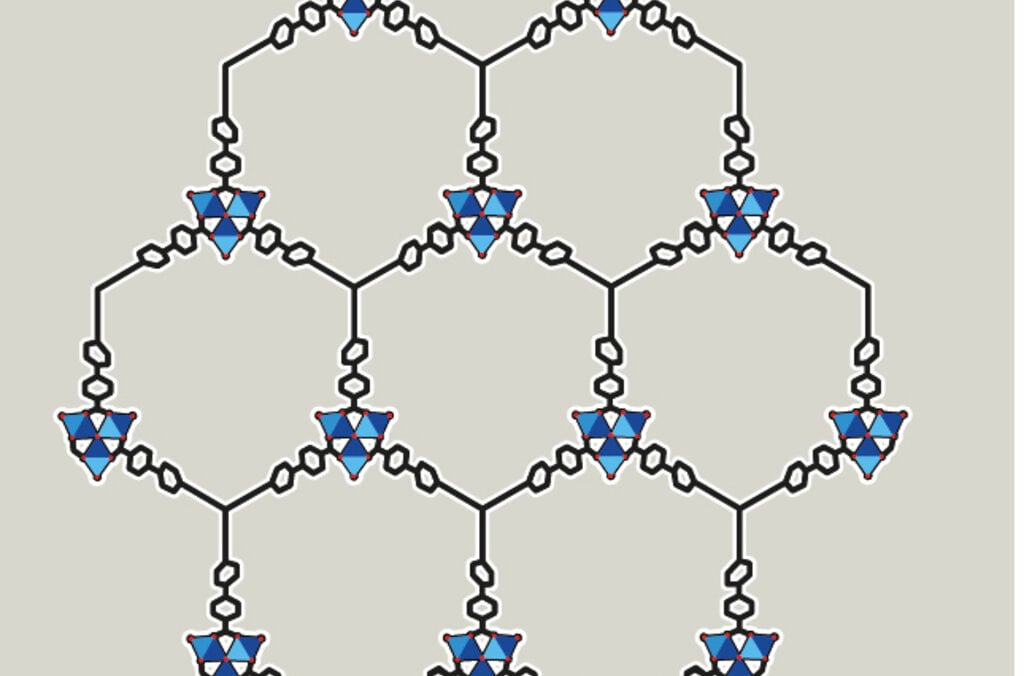

While Kitagawa was experimenting in Japan, Omar Yaghi started to think about how the material could be created in a more controlled way. He wanted to join together chemical building blocks into large crystals.

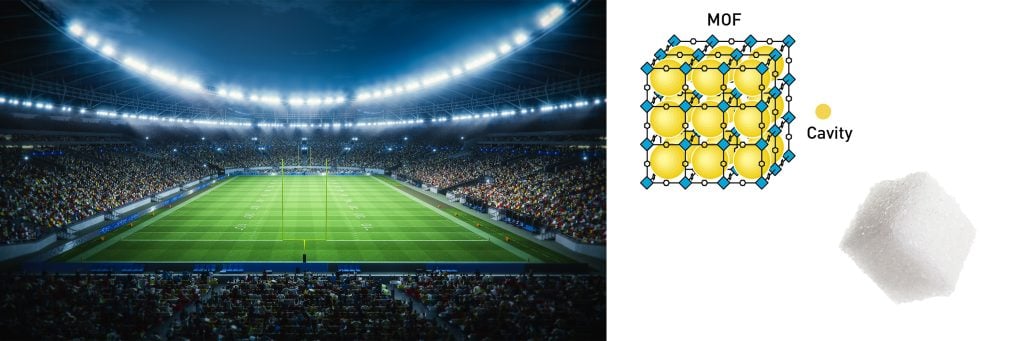

He managed to develop a new type of MOFs that were incredibly airy but still very stable. Despite the fact that each MOF was no larger than a sugar cube, the surface in the material’s cavity was as big as a football pitch. In other words, it resembled Hermione’s handbag in the Harry Potter stories. Despite its small size, it can hold almost anything.

Omar Yaghi also showed how to alter and customise MOFs to give them new and desired properties.

The 2025 Nobel Prize laureates in chemistry

Richard Robson is a professor at the University of Melbourne in Australia. In an interview, he said that many people initially didn’t believe in his idea: “Some people thought it was a whole load of rubbish. But it didn’t turn out that way.”

Susumu Kitagawa is a professor at Kyoto University in Japan. He has said that in his work as a scientist, he has followed an important principle – to try to see “the usefulness of useless”.

Omar Yaghi is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, in the United States. He came to the United States as a refugee from Jordan. His first contact with chemistry was when he sneaked into the school’s closed library and randomly picked a book off the shelf. There, he saw images of molecules that fascinated him.

For the greatest benefit to humankind

MOFs offer previously unimaginable abilities to customise new materials with new features. You can see some examples in the images.

In this short video, you will learn a little bit more about the discoveries made by the laureates and why they confer the greatest benefit to humankind:

Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2025

Transcript from an interview with the 2008 chemistry laureates

Interview with the 2008 Nobel Laureates in Chemistry Osamu Shimomura, Martin Chalfie and Roger Y. Tsien, 6 December 2008. The interviewer is Adam Smith, Editor-in-Chief of Nobelprize.org.

Osamu Shimomura, Martin Chalfie, Roger Tsien, welcome to Stockholm and congratulations on the award of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Martin Chalfie: Thank you.

As I’m sure you’ve been told many times, this is the 100th time that the Nobel Prize in Chemistry has been awarded.

Martin Chalfie: It’s the first time I’ve heard that.

It seems to be an auspicious prize. Of course, the prize began in 1901, but then there were various years missed because of the two world wars, so this is the 100th. This prize is an amazing example of how research in one field leads to unexpected results in another and I’d like to come back to that in a minute, but I’d like to start by asking about your various scientific beginnings. If we could start with you Professor Shimomura, you grew up in wartime China and Japan and indeed you were close to Nagasaki when the atomic bomb exploded there.

Osamu Shimomura: Yes, I was about 15 km northeast of Nagasaki city.

You saw the blast indeed.

Osamu Shimomura: I saw B-25s heading to Nagasaki. Then, after a few seconds, I saw a very strong flash. I was blinded, and another about 30-40 seconds. I had a very strong pressure wave through the ears, but I didn’t know what had happened.

No of course, yes, goodness. One can only imagine the devastation to society caused by this. How did you find your scientific feet, so to speak, how did you become a scientist in the aftermath of all this?

Osamu Shimomura: After the war, I couldn’t find any school to study, so I just wasted, idle, two years. Then the third year I heard a rumour that Nagasaki College of Medicine, medical college, no, I’m sorry, pharmaceutical college, is going to make a temporary campus near my home, so I applied. I was accepted, so I started at the pharmacy school. That was the beginning of chemistry oriented …

Yes. Professor Chalfie, I’ve read that when you were at Harvard you liked to describe yourself as a swimmer primarily.

Martin Chalfie: That’s probably one of my freshman roommates who said that but yes, I was a swimmer.

What turned you on to science then?

Martin Chalfie: I hadn’t really decided what to major in, in fact after my junior year in college I worked in a laboratory and went the entire summer not getting one experiment to succeed. At that point I decided that maybe science was not the area I should be going into, although I had been excited about it since I was a young kid, so for several years I did many things other than research and eventually wound up teaching in a high school. Among other things I taught chemistry and over the summer we had time for a break, and I was able to get myself a job in a laboratory, a friend had suggested going to the lab and I had a very good experience in the lab, the experiments worked. An idea had worked and I was very excited about the idea that this might be something I would like to do. That gave me the confidence to go and apply to graduate school and that’s how it all started.

Presumably you got used to the idea that experiments don’t always work.

Martin Chalfie: Unfortunately, all the time.

Profession Tsien, you came from a background of scientists, your family have …

Roger Y. Tsien: Mainly engineers to be, I think, more accurate. I guess the family was oriented toward science and technology and I did get a chemistry set as a small kid, and I tried and found it rather boring because all the experiments were very safe. But then I came across a book in the school library and I’m guessing now that I’ve reconstructed only a few days ago, because of the Nobel Museum’s request for artefacts, that this probably was when I was only about eight years old. It had so much cooler experiments, they were a little more dangerous and required corrosive chemicals and things like that. Somehow maybe my father helped me get some of them and I tried them and found that they were really neat. That got me started doing experiments at home in the basement, which was worrying my parents, but they were also a mixture of pride given the scientific orientation of the family but also fear that I was going to either burn myself up or blow up the house or whatever.

In high school, I wound up doing well on exams to the point where I got some first prize, I think in 10th grade in the chemistry exam, the school forced me to take it again because they got the prize money, not me. It was their only free money that wasn’t allocated by the township of Livingston, so they got to spend it as they liked, so they really wanted me to do well and the next year I got second prize and the next year after that I got third prize, so I was on a steady downhill slope. When I got to college I found chemistry, as taught at Harvard, was so awful that I resolved never to touch chemistry anymore, so there’s some ups and downs in this process.

Mostly ups it sounds like. You also won something called the Westinghouse Talent Search.

Roger Y. Tsien: Science Talent Search, yes, that was in my senior year. That got me the scholarship to go to Harvard. I guess I was a chemistry hotshot at that stage but as I said, a few years later, especially during the Vietnam War and all the student protests, I had decided that I might, probably some other area of science but certainly not chemistry.

But as you were saying, eight is very young.

Roger Y. Tsien: That was the really beginning.

Sure, but you sound like you were becoming a scientist much earlier than most people.

Roger Y. Tsien: As I said, between the genetics and sort of what my parents said, to be honest, growing up as one of the very few kids of Asian origin in a town that didn’t have any, science and technology were safer things to do than to try to be intellectual in an area like literature or theatre or something, that just was not going to be easy in American culture at the time. I guess that still tends to drive, the famous Asian nerd stereotype tends to still apply, a little bit, not quite as much as it did when I was growing up.

Thank you. As I was saying, this is an example of research in one area which was the search for light emitting molecules in nature leading to discoveries in cell biology which could not have been predicted. If we start with the beginnings, you Professor Shimomura were looking for light emitting molecules from a mollusc in Japan which you successful found, you found the protein and then on the strength of that paper, you were asked to go to Princeton where you started working on this jellyfish.

Osamu Shimomura: Yes.

Aequorea Victoria, and this is a small jellyfish.

Osamu Shimomura: I don’t call it Aequorea Victoria, I call it Aequorea Aequorea.

Okay, and it’s a small jellyfish.

Osamu Shimomura: Yes, about this.

To work on it you had to collect hundreds of thousands of specimens.

Osamu Shimomura: Yes.

Could you tell me about these collecting expeditions a little bit?

Osamu Shimomura: I started to study Aequorea in 1960 and that year, the main purpose was just to find out how we can extract that luminescent protein, which is called aequorin, the protein I found the result. We collected about 10,000 jellyfish that year and purified. At the Princeton I found aequorin and while I was purifyingwithaequorin, I saw a very small amount of a green fluorescent substance that was a purifying substance too. I found that was a protein. That protein was later named the green fluorescent protein.

Yes. But in an earlier phone call you said that you had collected 850,000 jellyfish over the course of 19 years.

Osamu Shimomura: Yes, I told you, that’s 1961, first year, that was only 10,000. But to find out that mechanism, that bioluminescence of the aequorin, we had to collect for 18 or 19 years and the total number we collected is 850,000.

Is it now an endangered species, are there any left after that?

Osamu Shimomura: No, I think there are plenty.

Roger Tsien: Professor Shimomura, my informant at Friday Harbor says that there are almost no jellyfish left.

Osamu Shimomura: Yes, but don’t blame me.

Roger Tsien: She does not blame you. Claudia Mills says it couldn’t’ be you because all the species of jellyfish have gone down even though you only collected one species, so that’s the evidence scientifically that it is something other than the collection. They grow up every year.

Do they know why they’ve decreased, is it pollution?

Roger Tsien: Nobody really knows but Claudia Mills feels that it is pollution and there is a whole attempt to clean up Puget Sound and protect the orcas as well as the jellyfish and all the species that have been having trouble.

Osamu Shimomura: Also temperature that is, I think – see how the temperature rises.

Roger Tsien: That’s also possible.

So green fluorescent protein was the reason that the jellyfish glowed green although they were excited themselves. Green fluorescent protein was itself excited by light emitted from aequorin which was a blue emitting protein. When you, Martin Chalfie, first heard about green fluorescent protein, you realised that it would make an excellent tag for cells in the worms that you worked in.

Martin Chalfie: For the twelve years before I heard about GFP, I heard of aequorin for some time but I hadn’t heard about GFP and for the 12 years before that, starting with my post-doc with Sydney Brenner in England I had been working on Caenorhabditis elegans, C. elegans, and nematode. At every one of my seminars I would bore people by listing all the wonderful reasons one would want to work on this worm and after I get through most of the list, at one point or another I would say, the animals are transparent. Having said that so many times over the years, I was primed to think about anything that would emit light or allow light to come out of this transparent animal.

Also, the year or two before I heard about this, we had been doing experiments to look at gene expression in the animal and at the time there were two primary ways of looking at where genes were active or where the proteins were being made. One was to put beta-galactosidase from the lacZ gene in E-coli into an organism and use a substrate that turned blue called X-gal and the other was to use antibodies and in both cases you had to do a lot of preparation to make sure the tissue was the right way. When I heard a seminar at first describing the jellyfish and then this wonderful protein, this green fluorescent protein, I got very excited and immediately ignored the rest of the seminar and just sat there fantasising about what would happen if we could possibly take this protein and allow it to be made inside of our worms and look at how things were being made.

Roger Tsien: Marty, do you remember whose seminar that was?

Martin Chalfie: It was Paul Brehm. At the time he was at Tufts, he’s now in Oregon, at the Vollum Institute, I think.

Following that seminar there was then this sort of stop/start relationship with Douglas Prasher who was cloning GFP.

Martin Chalfie: I recently found a piece of paper that I had scribbled notes all over and it appears that the next day after Paul Brehm’s seminar I called him, talked to him and talked to other people that were working on GFP, trying to find the person who was in the process of cloning the DNA for the gene and that was Douglas Prasher. We had this wonderful conversation and at the end of it we decided we were going to collaborate as soon as he had finished cloning the gene. Of course, before he cloned the gene I got married and the woman I married, Tulle Hazelrigg, was also a scientist, was living 2,000 miles away. I had a sabbatical leave coming and so I decided this is what I should do with the sabbatical leave, I’ll go to her lab.

I go to her lab and while I was there, was when Douglas finished the cloning of the cDNA and tried to contact me and couldn’t find me and decided – maybe because somebody gave him the wrong message when they answered the phone – that I had dropped out of science. I just assumed that he hadn’t been able to clone the DNA and hadn’t called me for that reason, so for about four years we just, or three years, we just were in mutual ignorance of each other’s progress or interest. It wasn’t until September of 1992 that I had a new graduate student come into the lab for a rotation period, a trial period, and she had worked on fluorescents as a master’s student. I told her this idea about using GFP, we looked at a database on the computer, found that in fact there was this paper just published or published earlier that year by Douglas showing that he had the sequence in the cDNA. We ran down to the library, found the article and fortunately it had his phone number on it – because I had misplaced his phone number – and called him up. We renewed the collaboration and he sent us the clone and one month later the student Ghia Euskirchen had green fluorescent bacteria and that was really the start of it. It was really remarkably fast once we found out that we still were both interested and able to do the experiment.

The first demonstration that GFP could be expressed in a different species.

Martin Chalfie: That’s right and it meant that there were no other proteins from the jellyfish that were needed for the formation of the fluorescent product. Before this people had been debating and I think the prevailing attitude was that because the peptide backbone of the protein had cyclised, that there must have been something to make that conversion, to make the cyclisation of the backbone and no-one knew really how that was made. We made the guess that nothing other than the protein itself was going to be needed and that turned out to be the right guess. If however we had not been able to get fluorescents out of the bacteria, we probably would have assumed something else was missing. I found a letter I wrote to Douglas saying, if it doesn’t work then we’re going to have to do this harder experiment, fortunately we didn’t have to.

Roger Tsien: Am I right, Marty, that Ghia then decided that fluorescent bacteria were no great big deal and that she would not continue in your lab?

Martin Chalfie: She had come as a rotation student, and she wanted to try other labs and so she decided that it would be a good idea to rotate into another lab and to see what the experience was there.

Roger Tsien: But did she stick with you?

Martin Chalfie: She stayed in the other lab.

She stayed in the other lab. Did she stay with science do you know?

Martin Chalfie: Oh yes.

I wanted to ask a little bit about Douglas Prasher because at the time of the announcement, some intrepid journalist went off and found him in Alabama. He’s not doing science anymore and it sort of sounded as if it rather well illustrated the knife edge of scientific research, that if you get it right you can come on to get Nobel Prizes but if things go a bit wrong or you don’t get your funding, it can all end. Is that a good illustration of how difficult it is to stay on the right track in science?

Martin Chalfie: I think that at least the little I know about the people that were working on GFP before we did our experiments, is that this was not being given a lot of support. That was rather difficult and I’m not sure that even subsequent to this, people writing grants just to work on the fluorescents or bioluminescence were getting as much support, so I think that that’s one of the aspects of the problem. The second thing is, I never wrote a grant to get money to do the GFP experiment, we had funds in the lab to do the experiments and we did them and I’m pretty sure that if I had written a grant, I would have been turned down: Where’s your preliminary data?

The advantage of having funding is that it allows you to do the unusual, the chancy, the risky experiment and then once you’ve done that, then of course they say: Oh yes, now we’ll give you more money to do that, but the first experiment we never wrote a grant. It would take too long to get the money, we wanted to know what the answer was when we finally were able to do it. I think those are two aspects to the work but Douglas’ contribution was absolutely critical to our being able to do the work that we did. In fact, if we go back and look at the paper, he is not thanked for his contribution, he is the senior author on the paper, the last author on the paper, we always have talked about each other as collaborators in this effort, so it wasn’t a situation where he did a small part and then was forgotten, it was a mutually agreed upon experiment, we talked about it a lot, we were collaborators.

It’s interesting that it’s hard to find funding for this basic speculative work which leads to such application. I imagine that it’s still quite hard to get money to go looking for molecules in nature.

Osamu Shimomura: It’s different I mean. 1990 and the 1960s were quite different. Around the 1960’s, to get funding from NSF, National Science Foundation, not so difficult. I didn’t have any problem, but the National Science Foundation does not give a large amount, but to continue our research we had no trouble until 1970.

Then things began to change.

Osamu Shimomura: I think change, yes.

Martin Chalfie: To give another example, I’ve been working since my post-doc on this nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans that Sydney Brenner really started the work on. He was fortunate enough to have the support of the Medical Research Council and he’s very famous in our field of having written a two-page grant application for the work that he wanted to do. That work now, many of us now consider has been the basis of three Nobel Prizes, the one in 2002 to John Sulston, Bob Horvitz and Sydney Brenner for developmental aspects of the animal, the prize in 2004 to Andy Fire and Craig Mello for RNA interference and now this prize. If I hadn’t work done on the transparent animal, we wouldn’t have it again. One has to wonder how many other secrets there are out there in organisms that we are not being able to look at because funding is not viewed as important for research, not perhaps very directed towards human health when in fact we need to learn so much more.

It was in your lab that GFP was sort of totally understood or at least better understood. The mechanism of its fluorescence was taken apart and all that and then reconstructed to create different coloured GFPs if you like, an expanded palette of fluorescent molecules which you could use in cell biology and you’ve also extended beyond using jellyfish proteins and you use proteins from corals and other things. What was the motivation behind all of this?

Roger Tsien: We have always wanted to look at proteins inside cells, not particularly at the time of C elegans but rather more mammalian cells. Already I have been collaborating with Susan Taylor to look at cyclic AMP, one of the important messengers inside cells and that process required getting hold of the natural protein in cells that senses cyclic AMP, which has got the long name cyclic AMP dependent protein kinase, or A kinase for short, and we had to put fluorescent tags on the two different sub-units. We used to put florisine on the catalytic sub-unit and rotamine on the regulatory sub-unit and put that all back together and inject this complicated mess inside a cell, which is really quite tricky to do.

And gives you a green and a red …

Roger Tsien: Green and a red colour and by watching cyclic AMP split these sub-units apart for which, by the way. Eddie Fischer and Eddie Krebs got the Nobel Prize some years earlier, but they didn’t do it with fluorescence, they did it by traditional biochemical means, we just put the tags on and used the same trick inside cells. We could follow cyclic AMP but it really was very cumbersome, and we realised that it would be so much easier if only we could fuse a genetic sequence that would encode a fluorescent protein.

I had already been thinking from 1989 or 1988 before I left Berkeley, because a colleague at Berkeley called Alex Glazer worked on these so called phycobiliproteins from blue-green algae which are also fluorescent and he had cloned out those genes. They come in a beautiful range of colours from green fluorescence all the way out to far red, wonderfully strong and when I heard that he’d cloned the genes, it occurred to me right away, Alex you’ve got a goldmine here, why don’t we just stick the phycobiliprotein gene and use it. I thought we could do that with cyclic AMP, then he informed me that it took at least two other enzymes out of the cyanobacteria, to put the chromophore in and even making the chromophore took several other enzymes so he said about trying it and it didn’t work. This was about 1988 or 1989, so that was my equivalent to Paul Brehm, but it was even more discouraging because it specifically said it was not going to be easy to get a visibly fluorescent protein.

When in 1992 or so when I was getting tired of labelling cyclic AMP or cyclic AMP dependent protein kinase, in that spring I typed into Medline green fluorescent protein, because I remembered from reviews on aequorin and aequorin was our big competitor for measuring calcium inside cells. I had of course read the reviews and I remembered that there was this supposedly nasty contaminant that you had to be very careful to get rid of, called the green fluorescent protein, if you weren’t careful you’d have contamination from GFP and I suddenly go, hey that’s just what I need and I typed in GFP or green fluorescent protein at the Medline and up popped Prasher’s paper. I’d never met Prasher before and again I ran to the library, got the phone number, called him and I guess because he’d not heard from you I suppose, he said Oh I’m happy to give you the gene but be warned, I tried to express a bacteria before I had the full length clone and it didn’t work so you’re probably going to have to work hard. I said Oh golly, we’re going to have to do the same thing that Alex Glazer had, we’re going to have to go back into the jellyfish and find all those damned enzymes that are necessary to make this thing glow. The other problem was, I didn’t have any molecular biologists in the lab, and we were not a molecular biology lab and it took me several months to wait until an unwitting molecular biologist applied to my lab to do calcium work.

Because that’s where you come from.

Roger Tsien: That’s what I was known for and so I diverted Roger Hime, Hey, now before you learn how to do calcium imaging, you know how to do molecular biology, let’s give this a try. I think we asked Douglas Prasher in the spring, but we didn’t get started until the fall and it was very soon when Douglas sent it. He said By the way someone else called Marty Chalfie is also working on it, and I heard not long after that the bacteria worked. We set about doing yeast specifically not to be treading on Marty’s toes, I mean you’d already done bacteria so we might as well do a different organ.

Did you two in fact just work in parallel and not collaborate at any point?

Roger Tsien: We had a few phone calls which there were some important pieces of advice passed, I think you gave us some advice on how to get it to express and we told you that we’d found a sequencing error. The gene that Douglas had sent both of us didn’t quite match what he published, fortunately it didn’t matter but Roger Hime was the one who spotted that. I think there was some useful interchange, but we weren’t directly collaborating but you see we needed two colours from the very beginning because we were originally labelling cyclic AMP dependent protein kinase with green and red because those two colours have to do something special called fluorescence resonance energy transfer and so we had the worse problem that not only we needed one colour, we needed two colours.

We immediately needed to set about changing this colour and understanding how it worked and amazingly the protein was relatively tolerant and pretty quickly, at least we got a blue, but then we had to clean up the green because the green turned out to have a messy spectrum and so we were forced to immediately start fixing the protein, making it better, making it work in mammalian cells. The jellyfish grows in Puget Sound, very cold water, never had any experience, never had any reason to express at mammalian body temperature and so we were forced to go and confront those problems.

How big is the palette now, how many different tags are there available to researchers who are just buying these in for their cell biological research?

Roger Tsien: Published in the literature probably 50 or 100 of which maybe 10 or 12 become popular, but that’s just the quirks of what got commercialised. People are developing more and it’s quite a confusing zoo for those who are not in the know, almost like buying a car now, you have to keep track of an awful lot of different models or buying a computer, right. Each one with their own little advantages and disadvantages.

Presumably some work together and some don’t.

Roger Tsien: Yes, that too.

What’s needed, what’s the next development phase for this area?

Roger Tsien: From my point of view, since we continue, we have finally reached the infrared in the fluorescence, but we had to abandon the jellyfish and corals to do so and we are trying to work on molecules that can perform similar functions but do not require gene transfer. The great power of the jellyfish protein and the corals is that you can deliver them by genes, genetic means give you tremendous precision and targeting but also limits you to those organisms into which you can put genes. For example, that does not readily include people and so for clinical use we need alternative. That’s where we’re going, both the longer wavelengths and not being chained to gene transfer.

Martin Chalfie: We are more the users of GFP now, but over time we’ve made modifications and the latest one that we’re interested in, and people have done something similar, is we’ve made a rather short-lived GFP because we’re interested in looking at the process whereby genes are not turned on but turned off in cells. Being able to ask the question what turns the gene off means that you have to make a mutant that keeps it on and if you take normal GFP, it’s a very stable protein, it stays around in cells and you don’t know when the gene is turned off because the protein is still there and stays around for a while. With the GFP we’ve made, it is destroyed and you can see it because there is no more fluorescence and then to look for mutants, all you have to do is look for organisms, animals, that have the fluorescence longer. It’s very easy to see a shining light in a sea of black and we’ve actually been able to do that. That’s been a very nice tool that we’ve developed in the last year or so and for us that’s the thing that is exciting us now because we’re being able to look at this other problem. A lot of times in science people first get interested in what turns things on and then suddenly realises that there’s this other aspect, that things are also turned off, so we’re now starting to get interested in that problem.

Professor Shimomura, presumably there are uncounted hoards of molecules of interest in nature still to be discovered and revealed and are people looking very actively for them or is it a quiet field?

Osamu Shimomura: I don’t know many people. I only know the field of bioluminescence study but in my field very few people are working. On the other hand, there are many, many /—/ programme in bioluminescence, there are many kinds of different bioluminescence systems but nobody studying at this moment. I’m sorry about that.

How do you attract people to work in this field?

Osamu Shimomura: How to attract? I don’t know. Just I hope many people are interested in bioluminescence. Excellent people are interested in bioluminescence and must study bioluminescence but actually at this moment, very few people studying it. People go to other field like biotechnology. I think that’s the biggest fear.

Roger Tsien: We have done a little bit of searching for other fluorescent proteins in collaboration and we tried a little bit ourselves, hunting through other species including collaborating the people who work on the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, a very rich source of corals, In general it turns out to be easier to take the existing gene and evolve it ourselves to do what we needed to do rather than search in nature. To be honest we’ve tried both but searching in nature is very time consuming, laborious and what you get out is suited for the organism’s purpose and not our research purposes. We wind up still having to revamp it, so it was quicker to generate other colours from the single coral protein that we’d worked out than to search for other corals for us, but if you want something different, you’re going to have to go back to nature.

For example, there’s a tremendous gold rush fever right now in the complimentary aspect, instead of using light to measure what cells do, using light to stimulate cells. The key there was to take a protein from a green alga and not a /—/ of cynanobacteria or jellyfish and this is the famous /—/ option /—/ and we hunted for that ourselves. I’m afraid we didn’t do too well and other people got it but once somebody else found it, again gold rush fever and there are a lot of other things out there in biology, not always bioluminescence but it’s again the similar problem. The early steps few people want to do because it’s high risk and you might spend a couple of years chasing a clone or a protein that you get nowhere but if it works, then everybody is eager, hoards will then jump on it.

Again this story illustrates it because Professor Shimomura was studying the protein for the protein’s sake, not for the application and that’s the key, you need people who are willing to look for the molecules.

Roger Tsien: I think you discovered it in 1962, the protein, or you published it in 1962?

Osamu Shimomura: Not the aequorin?

Roger Tsien: No, green fluorescent protein. You published in 1962?

Osamu Shimomura: 1962.

Roger Tsien: 1962 and Prasher’s paper on the cloning was 1992, so that’s 30 years that GFP was studied by almost nobody. Then from 1992 onward, suddenly once he cloned a gene and you showed that it became fluorescent, that’s only been 16 years now, roughly half the time of the first 30 years and then 25,000 papers or 30,000 papers have come out now. It’s a tremendously steeply rising exponential phase. Once people see that the truly risky early part is there’s a guarantee that something there works, lots of people then are eager to jump on the bandwagon.

Martin Chalfie: But I also think that one aspect of this whole story alluded to is that if the work had not begun with the green fluorescent protein and the initial applications became apparent to people, I don’t think people would have looked for the coral proteins. I think that the coral proteins for all the initial problems and modifications, those were things that were really important in changing our view of what the colours were and also just expanding our view of what we should be looking at, not just thinking about the jellyfish protein and so I think that was very important. I also have a reaction to this general conversation which is, I think as we’ve been talking here we’ve sort of put the blame on, well there’s some sexy part of science that people go to and then there’s the other parts that are not as sexy or not as interesting, as if everyone has the same idea about what’s important in science. Clearly there are things that attract more people than others, but I think there’s an element, if you will, of blame that should go to government agencies for funding and the emphasis that’s put on money that goes, for example in the United States to NSF for this sort of work as opposed to NIH for the work that it supports. I think that there has been a very big push in the United States for example to what’s referred to often as translational research.

This is something I think about a lot and I wonder about because the implication is that, well we’ve learned enough and now we should translate that information into, just pick those discoveries and apply them to the clinic and translate them into a health-related situation and so we can gain the benefits of all this knowledge. The problem with that is that of course there’s a vast amount that we don’t know and as several people have said, you need something to translate to be able to do translational research and I think we’re seeing how ignorant we are rather than whether we’re ready to apply it. The other thing is, I think that people often think about what the implication of their work is going to be and so I’m not sure we have a great need to push for applications. I think that’s something on the minds of virtually everyone I know, so I don’t think that’s a problem. I think that support by the funding agencies is an important aspect in directing where money goes for training grants, where money goes for research grants and so on.

The prize that you’ve been awarded is the Nobel Prize in Chemistry and yet none of you are chemists, you’ve steered away from chemistry as you said.

Roger Tsien: No, I became a chemist again, half of the chemistry department actually. When I do experiments with my own hands, which only happens around Christmas to New Years normally when the emails slow down, I actually do chemical reactions. In the end, what I didn’t finish saying is that in graduate school I realised that in order to do biology the way I wanted, I had to become a chemist again because that was the source of the molecular tools. When I said ‘I don’t know how to do molecular biology’ – I still don’t really know how to do that – but I do know how to do old-fashioned organic synthesis. When I mentioned that we’re trying to avoid having to use gene therapy, we are back to synthetic chemistry, so we’ve always had that mixture at least, since I became a successful researcher. I was describing the failures of being a student earlier.

But that was exactly where I was going. The idea that these aren’t hard and fast disciplines, there needs to be a tremendous amount of interchange between them. Do you think that young people coming into the subjects realise just how much potential shift there can be, that if you start as a chemist or a biologist or whatever, you can move around, you should move around?

Roger Tsien: You should and there’s a great deal of lip service to it. More people are now attracted to this so-called area of chemical biology, which is the new buzz word. Of course sometimes you wonder how is that different from biochemistry, which has been around a lot longer. It still tends to be easier for people trained in chemistry to become biologists than vice versa, but the boundaries are somewhat dissolving but it’s still quite tricky when it comes to difficult things like getting your first faculty appointment or getting tenure. Suddenly those disciplinary boundaries suddenly rear up in the room where the decisions are being made unless people argue, Oh do we really want that person. We’re a chemistry department, that’s really developmental biology, why don’t we let the biologists hire this guy? Everyone giving lip service into disciplinaria is great, but there’s still some serious problems, barriers. We are all forced to form communities and draw some boundaries.

Martin Chalfie: But I think also there’s an aspect that a little bit of this is going to be driven by students. When I talked to the chair of our physics department, he says that they’re not sure about how to hire someone that’s a biophysicist and we’re in the process of looking for people that take up this rather nebulous term. He always relates a story that one of the more prominent member of this department said that he himself was not sure about this. Approximately half of the physics students come to him and say, This is the area I want to work in, so there’s a very big push in a sense from below to have a department that actually is looking out and making connections. Found that Columbia, yes, there’s a lot of lip service, but I think there’s also some real movement in terms of there are people in our chemistry department that would very easily fit into the biology department and vice versa. There’s been more collaboration between the departments than I’ve ever seen in my 26 years there, so I’ve seen that a lot.

But I want to get back to what I thought was your original question which was that this is a prize in chemistry. I’m the chair of a biology department. I’m glad the committee never looked at my chemistry grades in college for making this decision. I’ve thought about this quite a bit of why is this a prize in chemistry. I realised that the prize is not to me, and I would say to any of the three of us, it’s to a rather remarkable molecule and that certainly is the preview of chemistry. It’s really a remarkable molecule on what it can be used for, it’s a remarkable molecule in terms of how it is formed and it’s really a recognition of some very interesting chemistry.

That’s an absolutely beautiful place to bring the interview to a close. I wanted to ask you though as one final question, whether you relish the idea of being Nobel Laureates because of course it brings with it all that sort of concomitant activity that must take you away from research. So how do you feel about it?

Martin Chalfie: I imagine that the number of interviews will go down precipitously and that there will be a lot more time to work in the lab. It does focus one to do this, but I feel quite honoured and I think it will open some doors as well. I think the three of us are basic researchers, interested in basic science and I think by winning this prize and by talking with people about the importance of basic research, that we have by the power of this prize a little more weight to our voices to actually get this idea across that a support of basic research is essential, not only for discoveries but also for the economy.

I notice that you got those points across in the YouTube video that you recorded in support of Barack Obama’s presidential campaign.

Martin Chalfie: Yes, it gave me an opportunity to say something I felt strongly about and I was able to do that.

Yes. Any comments.

Roger Tsien:

Of course it’s a great honour. It’s a bit daunting, especially because I know perfectly well I’m not any smarter than I was before October 8th, but suddenly people want to listen to me much more and I get invitations to speak at conferences on which I know absolutely nothing like soybean growing or things like that. There’s a certain fear also, a worry that it’s such a daunting responsibility that we are held up as these symbols when we’re just scientists and not so different from what we were a few months ago and yet now there’s much more responsibility in saying the right things. It’s obviously a wonderful experience in some ways and it’s also a little bit daunting too.

Martin Chalfie: There’s one other thing that I wonder about mainly because of my past reactions. I’ve been somewhat scared of being in the presence of people that I knew had the Nobel Prize and I now realise that that was a completely silly way of reacting. I’d sort of put them on a pedestal or thought about them in a particular way. Now I’m older and I see that this was perhaps a silly way of acting, but it also gives us some responsibility to be able to put people at ease so that they don’t feel this way because I think there might be a danger of being separated from the very people we want to be talking with and that’s our students.

That’s a beautiful point to finish on. Thank you very much indeed for taking the time to speak to me and I wish you a wonderful week here in Stockholm. Thank you.

Martin Chalfie: It’s going to be great.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2024

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2023

Nobel Prize lessons – Chemistry prize 2023

Moungi Bawendi, Louis Brus and Aleksey Yekimov are awarded the 2023 chemistry prize for the discovery and development of nanotechnology’s smallest components – quantum dots. Quantum dots are nanoparticles that are so small that their size determines their properties, including the colour of light they emit. These luminous attributes are now utilised in making television and display screens. They can also be used to guide surgeons in tasks such as removing tumours from the body.

This is a ready to use Nobel Prize lesson on the 2023 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The lesson is designed to take 45 minutes and includes a slideshow with a speaker’s manuscript, a video and a student assignment.

1. Show the slideshow (15 min)

Show the slides, using the speaker’s manuscript.

Speaker’s Manuscript (PDF 220 Kb)

2. Show the interview (5 min)

3. Student assignment (15 min)

Let the students work with the assignment.

Student assignment (PDF 350 Kb)

4. Conclusion (10 min)

Summarise the work with the assignment and capture any questions from the students.

Links for further information

Press release for the 2023 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Popular information for the 2023 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

A Swedish version of the lesson is available at nobelprizemuseum.se

More about the Nobel Prize and its founder in the lesson “Alfred Nobel and the Nobel Prize”

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2022

Transcript from an interview with the 2005 chemistry laureates

Interview with the 2005 Nobel Laureates in Chemistry Robert H. Grubbs and Richard R. Schrock, by Joanna Rose, science writer, 6 December 2005, during the Nobel Week in Stockholm, Sweden.

Dr Grubbs and Dr Schrock, my congratulations to the Nobel Prize and welcome to this interview and to Stockholm.

Richard Schrock: Thank you.

Two months have gone since you got the message from Stockholm, what happened during this time, Dr Grubbs?

Robert Grubbs: It seems like it’s been a very long time, many things have happened with many interviews and many events. The other fun thing has been many people who I’ve lost track with over the years have gotten back in touch with me, and so we’ve re-established a lot of friendships which we’ve lost over the years.

And the message caught you in New Zealand actually?

Robert Grubbs: New Zealand, yes.

In the middle of the night?

Robert Grubbs: Yes, late in the evening I was …

Richard Schrock: 12:30 or something, right?

Robert Grubbs: Yes, it was 10:30 at night.

Richard Schrock: 10:30 at night?

Robert Grubbs: Yes, so there were the crazy time changes, so yes. I was there on a fellowship teaching a course, so I came back from a trip and then the call came and I taught my course the next morning, so we finished up.

I see. Maybe it was worse in the States, you got that call in the morning?

Richard Schrock: 5:30.

5:30, well that’s …

Richard Schrock: I was up having breakfast, coffee, I usually get up at 5 or 5:30.

I see, and go to work that early? Before all your students come?

Richard Schrock: No, I don’t go to work, I catch up on e-mails and do some work on a paper or whatever, and then go in after the traffic at 9 or 9:30.

And what happened after this call? The first one?

Richard Schrock: After the call a lot of things happened, people started turning up with cameras and my neighbour came over and the telephone started ringing and finally I had to take it off the hook because it was ringing constantly, as soon as I would put it down it would ring. Many people were having their automatic diallers dial my phone number.

Could you pursue your work after that?

Robert Grubbs: Yes, it changed a bit but not much. I did return back to California and started teaching a course there and I’ve kept my research group going and written papers and so life goes on. It just adds a few extra things.

I see, so now you are back on the track, the life is like normal.

Robert Grubbs: Well, not totally normal, no, no.

Richard Schrock: Ah, I wouldn’t say normal.

Robert Grubbs: Not normal but…! But yes.

How did you become involved in science if you go back?

Robert Grubbs: For me it was probably goes back to a teacher in junior high, middle school, who was an outstanding teacher and who started challenging me and getting me interested in science, and so it continued from there. It took many different variations along the way until I arrived at chemistry, but it was still always a science emphasis.

And you dr Schrock?

Richard Schrock: I’ve always been curious about things and interested in making things and I still work a lot with my hands in wood working and so on. When I was maybe eight years old, my second oldest brother Ted gave me what we call the proverbial chemistry set and so that got me interested in chemistry. I decided to channel my efforts in that direction and never really changed, I kept with chemistry more or less.

Some dangerous thing to get, the chemistry set, to put it in the hands of a child.

Richard Schrock: Back then they were pretty good things, yes, a lot of stuff in it.

No accidents?

Richard Schrock: I wouldn’t say no actually, but I have all my fingers and toes.

Robert Grubbs: That’s why it keeps you in chemistry is the explosions, the accidents.

Are you the kind of nerds that do just nothing but science?

Robert Grubbs: I don’t know about that, we do many things. I know Dick has many hobbies as do I, other than chemistry.

Yes like?

Robert Grubbs: It changes over the years. From early days I was active in sports and then rock climbing and more recently just walking as I’ve gotten older. And also wood working and building and construction, so I’ve done all those things too.

Did you do walking in New Zealand?

Robert Grubbs: I did walking yes, that was a part of the reason I went to New Zealand, was to walk, I didn’t walk as much I’d like but it was still very good.

Because of the message or …?

Robert Grubbs: Partially, and because also the weather was very snowy and wet. So we had one really good walk in the snow which for a southern Californian boy is an interesting thing.

I see. And what do you do besides science?

Richard Schrock: I used to play sports, not seriously, just casually, and I still do physical exercise but I do wood working, my father was a carpenter and so I have a big wood working shop in my basement, it gets bigger and bigger as my sons leave and so on. I love to cook, I like to listen to music, I don’t play any instrument but I like to take pictures again and, you know, quite a few things, I would say my most serious hobby is wood working.

Maybe you can tell us more about the discovery? I know that Dr Chauvin made the discovery first and very early, and then it took like two decades almost until you came with a new idea.

Richard Schrock: Maybe you’d better tell that one, Robert.

Robert Grubbs: That was pretty early on yes.

Richard Schrock: He was involved in a lot of the early stage.

Robert Grubbs: I was involved in it earlier.

Richard Schrock: Quite crowded there for a while.

Robert Grubbs: Yes, so it was a … I mean the reaction was discovered in the 1960’s as an accident, and the real question was … I learned about in when I was a post doc in 1967, -68, -69 time frame. The reaction was quite new, and no-one had any idea how it happened, and so that was what really attracted me to it was trying to understand how this crazy reaction happened. We started doing some experiments and then there were a lot of different mechanisms proposed to how the reaction takes place and we were trying to sort those out, and Chauvin proposed the mechanism which was consistent with some data, and so we were involved in developing some of the mechanistic studies, labelling studies which demonstrated that his mechanism was probably the right one, along with Katz and a few other people. Then that really set the definition for what the catalyst needed to be, and then we started working for years, Fred Tebbe, who you worked with made some catalysts that worked, not very well, but we started using those as model studies and then Dick developed some catalysts that were really outstanding catalysts, and they did a lot of things, and we started working with those. Then we were lucky to find another different direction to go in with different kinds of metals and ended up making another catalyst which now has been moving along very rapidly. But there really wasn’t a discovery, it’s been a situation of changes and additions and …

Slow work.

Robert Grubbs: Slow work and finding something and then pointing it in a new direction and then following that direction until something changes and then you go in the next direction.

And you never give up.

Robert Grubbs: You shouldn’t give up, no, still working hard. Still lots of problems to solve.

On the same reaction?

Robert Grubbs: The same reaction, still lots of problems to solve, yes.

And do you remember how you got the idea? It was also the slow work…

Richard Schrock: In my case I was at DuPont, so for three years, from 1972-75, about the time that Bob and Chauvin and others were investigating the mechanism. I discovered a kind of compound that had this new ligand in it, this new linkage that was part of the Chauvin mechanism, although at that time I don’t think I really knew about the Chauvin paper because that wasn’t known for some time, I think exactly who was first …

Was it in French or …

Robert Grubbs: It was in French yes.

Is this the obstacle? That it was in French?

Robert Grubbs: It was in French and it wasn’t …

Richard Schrock: What journal was it in?

Robert Grubbs: It was in a polymer journal which …

Richard Schrock: Polymer, right.

Robert Grubbs: … a lot of people didn’t read, so it was some time before …

Richard Schrock: See, we’re basically organometallic chemists, he’s an organic chemist, not an inorganic chemist, and Chauvin is a polymer chemist, so he published in French, polymer …

Specialisation.

Richard Schrock: … journals that we didn’t read every day.

Robert Grubbs: A lot of people didn’t read it, in fact someone else sort of rediscovered what he discovered later, but anyway.

Richard Schrock: I was at DuPont and I was doing tantalum chemistry which is one of the metals right next door to the ones that work well, or that first worked well, molybdenum and tungsten, and it turned out that I made a type of compound that was different, it had this required linkage in it. I thought maybe it’s possible that this one would have something to do with this crazy new reaction, and so it took about I guess 1980 was the year that I started to put it all together I would say, so that’s about six years later, after I moved to MIT in 1975. But tantalum, it works out, is not what I call a classical catalyst, it’s not something that makes this thing easily, you have to work at it very hard, but molybdenum and tungsten we found out what was the right combination and then we could make, again by designing, something that’s stable and will do the reaction very rapidly and do everything that Chauvin said it should do, make these intermediates and we could get structures of them and so on. And then we could continue to refine the catalysts and move ahead. There is another part of this chemistry that was not actually mentioned, usually, in the Nobel Prize statements and that is there is a triple bond version called alkyne metathesis which is very closely related, and we discovered that similar compounds will actually, could be made that would do that reaction.

Robert Grubbs: What year did you come to Caltech?

Richard Schrock: -86.

Robert Grubbs: -86, okay.

Richard Schrock: We published one paper …

Robert Grubbs: One paper together yes, in ‘86, on tantalum.

Richard Schrock: No, it was tungsten. The first tungsten catalyst.

Robert Grubbs: Okay, that’s right.

Richard Schrock: I would say was the modern one, they say 1990, but actually it was 1986, was the one that I actually brought to Caltech and we made some polymers and we proved that it did what it’s supposed to do, and so that was the one and only paper that we published together.

Did you start to work together then? Or you knew each other before?

Robert Grubbs: We knew each other long before.

Richard Schrock: We knew each other since the early 1970s I would say.

Robert Grubbs: Early -70’s, yes.

Because you work in the same field?

Robert Grubbs: The same field, work in the same field, go to the same meetings. I remember the first basketball game we played together. I still have a scar I think from that game.

At the conference or…?

Robert Grubbs: It was a conference, that’s right yes.

So this is what you do at conferences?

Robert Grubbs: Yes, we decided we should never do that again.

Richard Schrock: So Bob did do a lot of further studies with these and similar molybdenum catalysts. I made more variations probably, since I’m an inorganic chemist, so I work more with making and designing catalysts and Bob with applying that chemistry to make polymers, and then really set his sights on organic chemistry. He was the first to really see the possibilities, since he’s an organic chemist, that one could influence organic chemistry powerfully.

But you worked in the industry?

Richard Schrock: Just for three years.

For three years.

Richard Schrock: Yes, from 1975, so for 30 years I’ve been at MIT.

What is the relation between applied science and fundamental science? Can you comment on that?

Robert Grubbs: I think they naturally sort of flow together, at least for me it’s been. We started out doing very fundamental work, we still do very fundamental work, but you also have to keep an eye for where it might be useful and then point it in that direction. Then once you get it going in the right direction there’s lots of people who will take that then and use it to make things and do the applied stuff. I try to do the fundamental and then point people in the direction that the applied stuff can happen and then there’s all kinds of wonderful people around who takes that and does nice things with it.

Richard Schrock: And the main idea is to control these catalysts and what they do and then you control it by making different catalysts and you know everything about them in a fundamental way, and then you can apply that knowledge to making a polymer of a certain type or doing a certain type of organic reaction. Then you can apply what you know with these catalysts, but it all begins with fundamentals.

Yes, but in the 1970’s there were lots of research laboratories in the industry, it’s not so many nowadays.

Robert Grubbs: It’s getting much harder.

Richard Schrock: They’re almost gone, I would say there’s nothing even close to what DuPont was, for example.

No.

Robert Grubbs: I mean DuPont was an amazing place.

In what way?

Robert Grubbs: It was like an academic laboratory.

Richard Schrock: Fundamental research.

Robert Grubbs: For fundamental research and that’s all gone. In fact there’s almost no real fundamental industrial labs any more. In one sense that’s okay because the universities are there to do the fundamental work. I think the problem now is the transition work, it’s that in the past, if you did fundamental work there was then someone in the company who had the understanding of the fundamental work and could do the transition part which then got it to the applied edge. That part seems to be missing now, and so we’re working really hard to try to come up with ways so that one can go from an academic laboratory and then get through this missing piece to the industrial part. And what’s happening now is that small companies are starting to fill in that gap.

And they are started by academics?

Robert Grubbs: In many cases by academics yes.

Richard Schrock: Like him for example.

Yes. That’s another sort of job, I would say.

Robert Grubbs: It’s another sort of job but if you do it right it’s a very fun job and not so difficult, if you find the right people to do that transition work.

So you work with a company and in academia?

Robert Grubbs: Yes. My job is in academia, but part of getting the technology, the fundamental stuff, we’ve developed two applications which after all one loves to see your stuff used and done. It was essential to build up this middle part and the only way to do that is to be involved in starting a company that is involved in that transition work. I tried doing it lots of other ways but it’s the only real way that I found to do it now. Dick’s also involved in the company too.

Richard Schrock: Yes, but not to such an extent. But they’re trying to get all of metathesis under their roof, I would say, and push it, which is good. And they will try to apply this reaction for pharmaceutical companies or for whoever wants to use it because it’s so universal in the sense that you can go in many directions. It’s a fundamental reaction, you can do many different things with it, and many companies might see some reaction that they could do in fact, and then they would license for example the possibility to do that from this company.

Robert Grubbs: But you need someone there who, as I say, that middle piece is missing, I mean for example DuPont used to do a lot of the fundamental work but they also could do the transition into the very applied stuff. But that’s all missing now. So I think that’s going to be the next generation of the way the technology develops.

There is also a question on going another way. How do you get information about what are the problems in the industry to solve in academia?

Robert Grubbs: Yes, that’s hard, but you don’t have to do that. What I’m finding now is that if you generally go around and you talk about the fundamentals, you talk about the places where the chemistry can be applied. The places where industrial chemists find applications always astounds me, you know, it becomes important and commercially viable, not for some fundamental chemical reason but for some small business reason which I have no idea about. It’s just been really fascinating to watch this happen, and there’s no way you can predict it or even think about it, and so you just put the science out there and get it to the point where people can understand it and use it and then they just find amazing applications.

There is one point on the road there that when science needs to become not so open as it’s used, we need to get patents and then you have to be secret about …

Richard Schrock: This is tricky and a question I often get is how is the chemistry used? What is being done with it exactly? Bob knows more than I do, but I don’t know because of this fact, and even people at materia may not know what exactly their catalyst’s being used for because naturally they want to keep it quiet…

It’s the company’s secrets.

Richard Schrock: Companies do not want you to know too much.

Robert Grubbs: Yes, and I know a lot I can’t talk about, but on the other hand I mean a lot of it is still getting to be known and the information does get out. At the academic side there was a change about seven or eight years ago which changed the way one could work. In the days before then you had to have a patent written and out before you could publish, and then the US patent office, and I think It’s now going around the world, is a thing called the provisional patent. This allows you then to basically claim an area without having a formal patent written, and then you have up to a year to write the formal patent, so that gives you a, as an academic that’s really been liberating in terms of how one can do patenting as well as publication, because in the end what we have to do is publish.

Yes. There are some other changes in science that maybe are more bothering, about how the public view science today compared with even ten years ago.

Richard Schrock: That’s hard.

Robert Grubbs: Yes, I’ll let you take that.

Richard Schrock: I think the public is as, the general public, it depends on the country I would say, but it’s lost the faith in science that we once had. After World War II and Sputnik of course, that created a stage for science and people looked to science to solve many problems, and now they’ve become maybe a little jaded as we would say, a little too accustomed to what progress we’ve made and they no longer have maybe the confidence in science, I think, that we had at that time for sure.

Robert Grubbs: Sputnik was the one that for, that was what changed the life in the US in terms of science, and at least in my generation, I was in high school when Sputnik went up and I remember precisely that, and it really paved the way for me to go into science and go through science, so that was important, but that’s getting harder and harder. I think as Dick said there’s a lot of faith being lost, there’s no at least in the US attitudes that are very non-scientific that are becoming prevalent, that are being supported at levels which make it difficult for science in many ways.

Who’s to blame for that? If you blame anything. Is it school systems?

Robert Grubbs: I don’t know, it’s really been frightening the last few years to watch the change happen.

Can you see it with your students? People who come to the universities?

Robert Grubbs: I don’t, not in our students, I mean we’re both at institutes of technology which have probably the two highest standards for admission in the US and so our students come in interested in science, wanting to do science, and so for our students that we work with everyday it’s not an issue. It’s outside of that group you see it.

Richard Schrock: And you see it through the funding agencies and the money they get which has, fortunately this year I think increased, but there have been some difficult years, and well, the government statements, our government and any government has positions, and sometimes they are not, shall we say, scientifically what we would like them to be. And that’s something that is very visible and it’s very distressing to see things said that are just not true or certainly debatable at best.

Robert Grubbs: The other thing is when we started out there was a great emphasis on doing fundamental science and over the last number of years … it’s not a bad thing but it’s a different thing, which is that even at the agencies that support fundamental work one has to say where this can be used, the applied end, and see it, and if we’d been starting out that way we’d have never started our work because there was no way in the world one could have imagined where this would go, it was just a fascinating reaction to look at.

Richard Schrock: And now you have to say how is this going to benefit mankind before you even know basically what you are going to discover or develop. We know now what this reaction has done but you cannot predict the future, and to say where it’s going to actually benefit mankind at a point where it’s fundamental research is impossible really.

Robert Grubbs: I mean after 35 years now working on this reaction I still get shocked very often about new thing it can do and new directions it would go in, so it’s a … I hope it stays for a few more years.

It’s fantastic, yes, and it’s just started with a happy end I would say, even if it’s not the end yet.

Robert Grubbs: Not the end yet no, I keep saying I have a few more years before I retire so I’ve got a lot more things to do.

Yes, I look forward to seeing what happens. Thank you very much.

Richard Schrock: We’re both young, we’re both young.

Thank you for the interview, and I hope you have a great time in Stockholm now.

Robert Grubbs: Thank you, thanks.

Richard Schrock: I’m sure we will.

Robert Grubbs: I’m sure we will yes.

Richard Schrock: Thank you.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.