How X-rays and crystals revealed the true nature of things

The story behind the 100-year-old discovery that continues to render Nobel Prizes.

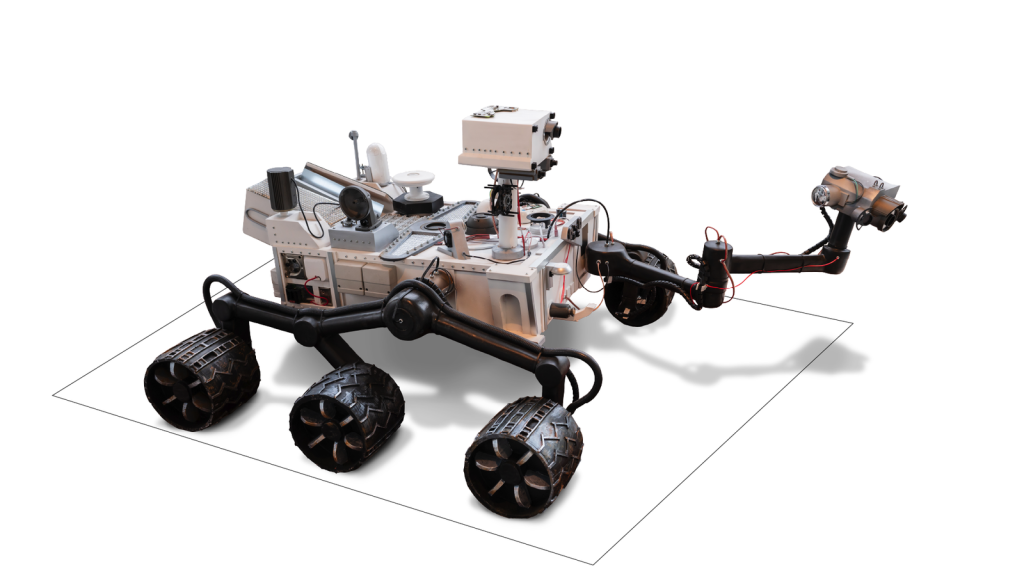

Alone in the Martian desert, a robot was looking for answers. In 2012, Nasa’s Curiosity rover scooped up a small pile of sand, ingested it, and blasted it with X-rays. The intrepid bot was going to find out what that sand was made of, which could in turn reveal information about the historical presence of water on Mars – because any water in this dusty, red plain was long gone.

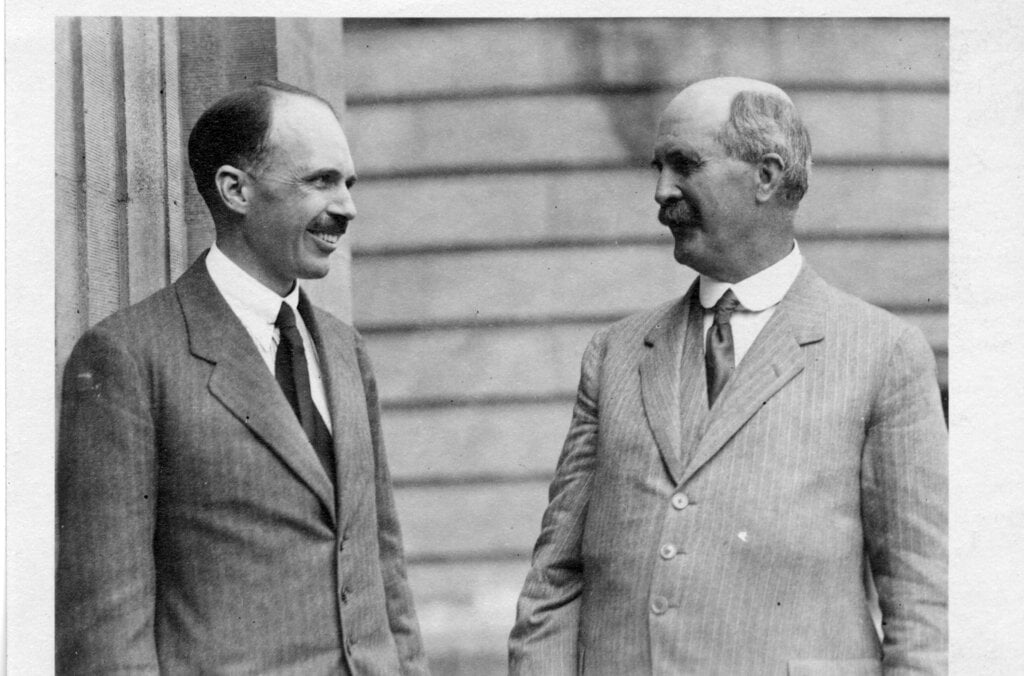

Nearly a century earlier, in 1915, William and Lawrence Bragg – a father and son team – had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their work on X-ray crystallography, a technique that makes it possible to determine the atomic and molecular structures of crystals by studying how X-rays diffract, or deviate, when they interact with them.

Many materials, from tiny proteins to metals, can form crystals, and X-ray crystallography became the gold standard for revealing how various forms of matter are put together.

Back on Earth, Michael Velbel at Michigan State University was waiting eagerly for data from Curiosity on Mars. This was the first time X-ray crystallography had ever been done on another planet.

“I was shadowing the mission all along,” recalls Velbel.

Curiosity’s analyses revealed details of the water content of minerals on Mars, which have given credence to – though not proved – the hypothesis that the planet had large bodies of water just a few hundred thousand years ago.

“We can finally get a grasp on that,” says Velbel.

Knowing what things are made of lets us do some amazing things. Analysis of atomic and molecular structures have helped scientists design drugs, unravel the secrets of DNA, and even make better batteries.

You can tell X-ray crystallography is important because it has played a role in numerous Nobel Prizes – some put the tally at more than two dozen. And yet few people know just how awesome a technique it is.

Regular patterns

“A lot of people call me ‘Chrystal the Crystallographer’ – or ‘C-squared’” jokes Chrystal Starbird at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She remembers the first time she used X-ray crystallography to determine a molecular structure. “I was looking at something no-one else had looked at before. I was like, ‘Wow, how cool is that!’”

If you’ve ever seen one of those ball-and-stick models of chemical substances, you’ll know what X-ray crystallographers are working towards. They want to find out what atoms are in a material and exactly how they are bonded together.

When Starbird does this kind of analysis, one key early step in the process is taking, say, a protein and working out how to grow crystals of it on a very small scale. Just as water forms ice crystals when it freezes, proteins can form very tiny crystals under certain conditions.

Those crystals are then harvested with tiny hair-like loops – which can be a very tricky procedure – and placed on an X-ray diffractometer.

The crystals are necessary because when you shine X-rays on their ordered structure, you get a regular diffraction pattern – precise markings specific to the chemical nature of the crystal in question.

However, proteins are much more complicated than water molecules so conditions must be just right for them to crystallise. Starbird may have to try hundreds of different approaches – using different chemicals, temperatures or humidity levels – before it works.

“I’m somebody who’s OK with delayed gratification,” she jokes.

Mapping insulin

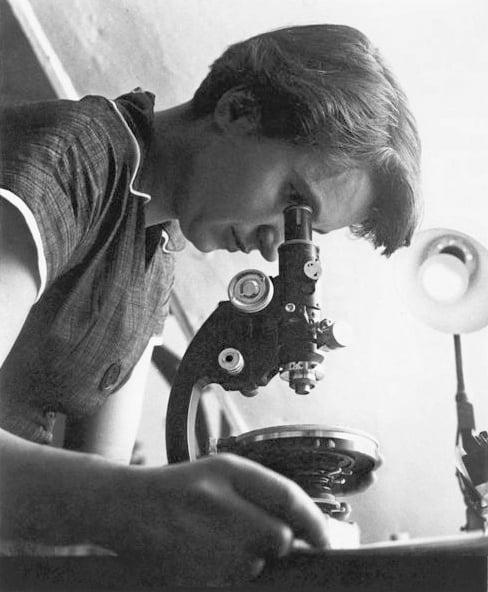

One scientist who would probably have related to that was Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin. She spent 34 years using X-ray crystallography to work out the structure of insulin, beginning in the 1930s. Insulin is a hormone that helps control blood sugar levels but Type 1 diabetics are unfortunately unable to produce it.

In Hodgkin’s case, obtaining the insulin crystals wasn’t especially difficult. But because insulin contains no fewer than 788 atoms, it took a long time for her to map the entire structure using early X-ray crystallographic methods. Her achievement made it much easier to mass-produce insulin for the treatment of diabetes.

By the time Hodgkin had finally finished, in 1969, she had already been awarded the 1964 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her X-ray crystallographic studies. She had also determined the structures of penicillin – an important antibiotic – and vitamin B12.

“She was a terrific inspiration.”

Elspeth Garman at the University of Oxford, on Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

She died in 1994. At a memorial service the following year, Max Perutz – who also received a joint Nobel Prize in Chemistry for crystallographic work – said, “Her X-ray cameras bared the intrinsic beauty beneath the rough surface of things.” He praised both her kindness and her “iron will” to succeed.

“She was a terrific inspiration,” says Elspeth Garman at the University of Oxford, who knew Hodgkin.

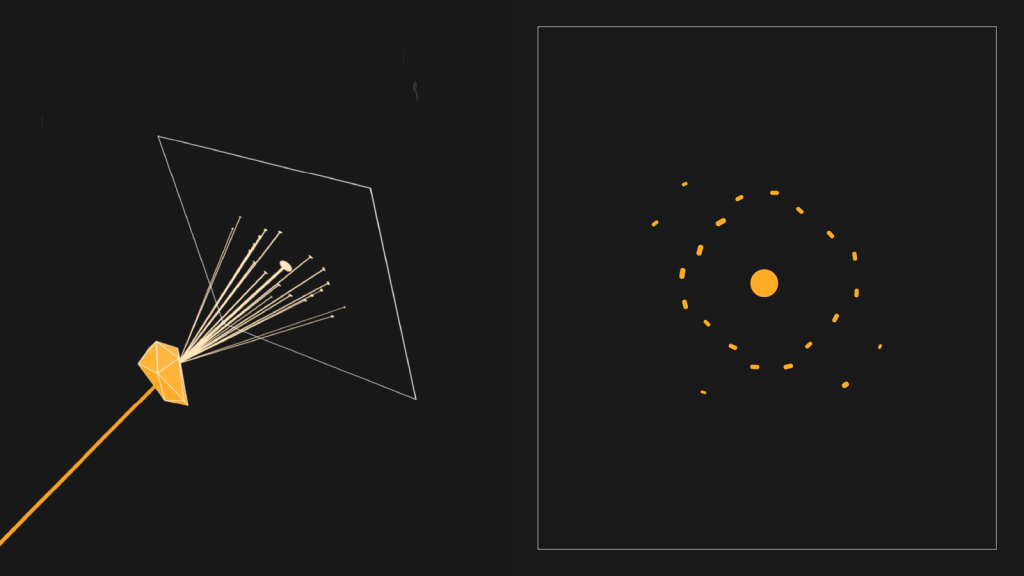

Garman describes an X-ray diffraction pattern as “an incredibly complicated reflection.” X-rays directed at a crystal structure interact with the electrons orbiting atoms inside that structure and diffract, leaving a detectable trace on (in Hodgkin’s day) X-ray photographic film nearby.

The result is a pattern, which you can painstakingly convert into a topographical map of the structure, or a three-dimensional model.

Women excelling

Garman notes that many women have excelled at X-ray crystallography. She credits the Braggs, in part, for this. “They had the most amazing academic tree of women that they encouraged and took on as graduate students when people in other fields didn’t,” she says.

Besides Hodgkin, there was also Rosalind Franklin, whose X-ray diffraction image of DNA was among many findings she made while trying to work out the structure of DNA. Some of her findings influenced Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins in their own endeavours on this subject. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work in 1962. Many argue Franklin never received sufficient credit.

X-ray crystallography has also been involved in more recent Nobel Prize-awarded work – including the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for genome-editing technology, which has roots in crystallographic studies of RNA.

One hugely important application of X-ray crystallography is in drug discovery. It has helped scientists find drugs for sickle-cell disease and even certain cancers, for example.

Rob van Montfort, group leader in the Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery at the UK’s Institute of Cancer Research, says crystallography can reveal which compounds could block or control key proteins in the body, and thus treat a disease.

“X-ray crystallography… provides pictures showing how, exactly, the compound binds to the molecule,” he explains.

Seeing inside batteries

Recent technological developments have allowed increasingly complex crystallography studies, Garman says.

At Diamond Light Source, a science facility in the UK, staff use X-ray beamlines to check the medicinal potential of compounds at high speed, by analysing potential binding-sites on a given protein. “Overnight, you could look at 200,” says Garman. “It’s absolutely staggering.”

Researchers have also used this approach to study battery materials – a key technology for the transition away from fossil fuels. Phil Chater, crystallography science group leader at Diamond Light Source, says X-ray crystallography reveals how the materials inside batteries can degrade over time.

Lithium-ion batteries work by allowing lithium ions to travel between layers of material – that’s how they charge up and discharge energy.

“Maintaining that [layer] structure is very important for the prolonged life of these batteries,” Chater says.

But crystallography allows you to see, sometimes, how layers are changing, affecting the ability of the ions to move in and out, he adds. Scientists can then search for ways of overcoming the problem.

A close look at comet ice?

X-ray crystallography has clearly made waves in many fields. But there’s an elephant in the room, says Garman.

A rival technique called cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is now enabling scientists to derive the structure of certain molecules in a completely different way – by firing beams of electrons at them. Some molecules have traditionally been too small for cryo-EM devices to see, however solutions are emerging on that front.

There’s also artificial intelligence (AI). If AI can accurately predict molecular structures, there may be less need to use X-ray crystallography for this task. But Starbird cautions that there are many structures AI doesn’t predict well.

“I think people have a misconception that crystallography might be done soon, because we have AI – we’re not even close to that,” she says.

The Braggs, presumably, would be glad to hear this. And X-ray crystallography devices may go on even more exciting adventures in the future. Velbel suggests sending one to a distant comet orbiting our sun.

“Wow. I’d want to see what comet ice looks like,” he says, explaining that we might find exciting mixtures of unusual compounds if we could study it up-close. “I think it would be fascinating.”

By Chris Baraniuk, BBC World Service. This content was created as a co-production between Nobel Prize Outreach and the BBC.

Published February 2026

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.