Ferdinand Buisson – Speed read

Ferdinand Buisson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, jointly with Ludwig Quidde, for his efforts for Franco-German reconciliation.

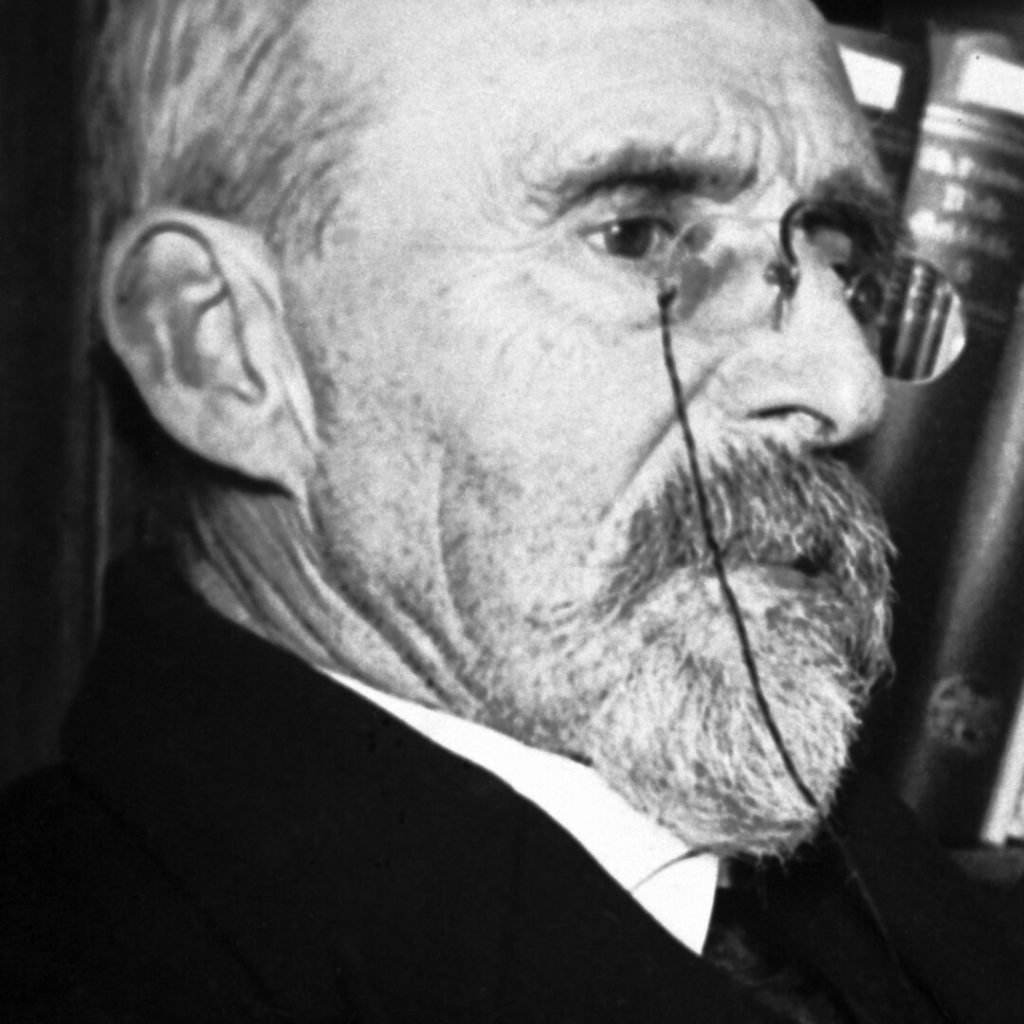

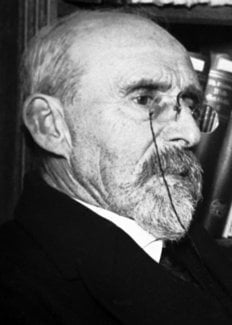

Full name: Ferdinand Édouard Buisson

Born: 20 December 1841, Paris, France

Died: 16 February 1932, Thieuloy-Saint-Antoine, France

Date awarded: 10 December 1927

For human rights and German-French reconciliation

Ferdinand Buisson was a professor in the theory of education at the renowned Sorbonne in Paris. He both wrote and spoke out against the intense anti-Semitism in French society and helped to found the French League for the Defence of the Rights of Man and the Citizen in 1898. As a member of parliament, he promoted women’s suffrage and fought against extreme French nationalism. During WWI, Buisson regarded Germany as the aggressor, but he strongly opposed the harsh measures inflicted on the country after the war. Fearing that frustrated Germans would start a revanchist war, Buisson organised French-German reconciliation meetings. It is for these efforts he was selected as peace prize laureate, together with co-laureate Ludwig Quidde from Germany.

”Buisson and his friends have not confined themselves merely to talking about the disarmament of hatred; they have sought to make it a living fact.”

– Fredrik Stang, Presentation Speech, 10 December 1927.

The Nobel Committee on Buisson

When Buisson was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, he received the following recommendation from the Nobel Committee advisor: Buisson had “untiringly … spent his entire life fighting for the rights of oppressed individuals and peoples, and today he stands as one of the noblest figures in French politics, as the country’s enlightened conscience.” When Buisson accepted the prize in Oslo, the chairman of the Nobel Committee said that “he spoke for the disarming of hate because this must take place before nations could disarm.”

”What has impressed me most about Buisson is … that this aging man has plunged into the battle for that which he calls the triumph of right with such an inspiring degree of youthful enthusiasm and energy.”

– Jacob Worm-Müller, Adviser’s report, “Reports 1925”, page 17, The Norwegian Nobel Institute.

Learn more

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Ferdinand Buisson – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Essay, May 31, 1928

Changes in Concepts of War and Peace

Read the Nobel Lecture

Pdf 34kB

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.

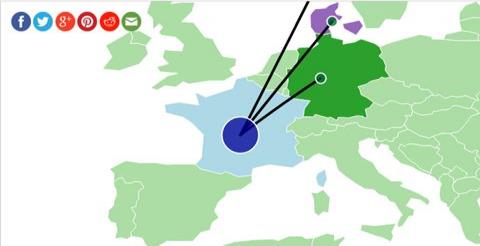

Ferdinand Buisson – Nominations

The Nobel Peace Prize 1927

Ferdinand Buisson, Ludwig Quidde

Nominated on 9 occasions for the Nobel Prize in

- Peace 1925, by Charles Robert Richet

- Peace 1925, by Hellmut von Gerlach

- Peace 1925, by Marius Moutet

- Peace 1925, by Hellmut von Gerlach

- Peace 1925, by Marius Moutet

- Peace 1927, by Charles Robert Richet

- Peace 1927, by Jacob Worm-Müller

- Peace 1927, by Ivar Berendsen

- Peace 1927, by A Aulard

Explore a visualization of the nominations

Search for nominees and nominators in the Nomination Archive

MLA style: “Ferdinand Buisson – Nominations”. Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 22 Jun 2018.

Ferdinand Buisson – Biographical

Ferdinand Édouard Buisson (December 20, 1841-February 16, 1932), «the world’s most persistent pacifist», was born in Paris, the son of a Protestant judge of the St.-Étienne Tribunal. For his ardent partisanship of pacifist, Radical-Socialist, anticlerical views he was vilified by journalists, attacked by clerics and conservative scholars, forced from public office by political slander, and even, at the age of eighty-seven, severely caned by a group of student protesters who disrupted a pacifist meeting at which he was speaking. A progressive educator, he played a vital role in the modernization of French primary education.

Buisson attended the Collège d’Argentan and the Lycée St.-Étienne but left school at the age of sixteen to help support the family when his father died. He completed his secondary education at the Lycée Condorcet and his undergraduate degree at the University of Paris, obtained an advanced degree and certification to teach philosophy, and much later, at the age of fifty-one, took his doctorate in literature.

In 1866, unwilling to swear allegiance to the Emperor and consequently unable to find a teaching post, he became an expatriate in Switzerland where he taught at the Académie de Neuchâtel. The following year he participated in the Geneva peace congress which founded the Ligue internationale de la paix et de la liberté. Among his writings during this period of exile are L’Abolition de la guerre par l’instruction [Abolishing War through Education], published in États-Unis de l’Europe, and revisions of his Christianisme libéral [Liberal Christianity], which develops the concept of a liberal faith in which organized religion is supplanted by a personal morality independently arrived at.

Returning to France after the defeat of Napoleon III in the Franco-Prussian War, Buisson began his career as an educational administrator. He was named an inspector of primary education in Paris by Jules Simon, the minister for education in the Third Republic, but because of his speeches and pamphlets pleading for a system of secular education, he was accused in the National Assembly of disrespect for the Bible and in the general outcry that ensued felt called upon to resign. Later he became secretary of the Statistical Commission on Primary Education, attended the Vienna and the Philadelphia Expositions as a delegate of the Ministry of Public Instruction, and prepared extensive reports on education in Austria and the United States. In August of 1878, Jules Ferry, who had been appointed minister for education, gave Buisson the post of inspector general of primary education in France and, in the following year, that of director of primary education, a position he held for the next seventeen years. During the 1880’s he collaborated with Ferry in drafting laws establishing free, compulsory, secular primary education in France, defended them in hard-fought legislative battles in the Chamber of Deputies, and finally participated in their implementation.

Buisson was scholar as well as administrator. In 1878 he edited and saw through publication the first volume of the four-volume work Dictionnaire de pédagogie et d’instruction primaire. In 1896 he became editor-in-chief of an influential journal of education, Manuel général d’instruction primaire. From 1896 to 1902 he was professor of education at the Sorbonne.

The Dreyfus Affair ignited Buisson’s desire to enter politics. Among the first of the ardent Dreyfusards when that affair exploded, he undertook a vehement writing and speaking campaign to reverse the Dreyfus decision and helped to found the League of the Rights of Man (1898) which grew out of the Dreyfus case and of which he became president in 1913. From 1902 to 1914 he was the elected deputy for the Seine. A Radical-Socialist, he supported compulsory, secular schooling; served as chairman of a commission on the issue of separation of church and state and as vice-chairman of a commission on proposals for social welfare legislation; sat on the Commission for Universal Suffrage where he upheld the vote for women and supported the principle of proportional representation.

Buisson returned to the Chamber in 1919. He criticized the Treaty of Versailles in an open letter dated May 23, 1919, but in other publications and in speeches endorsed the League of Nations as a practical instrument in the effort to achieve international peace. Hoping to unite leftist groups, rejuvenate the radical party, and win support for his educational policies, he formed the League of the Republic in 1921. The new organization did not prevent his defeat in the election of 1924, however, and Buisson, now eighty-three, retired to Thieuloy-Saint-Antoine in Oise. There he became a municipal councillor and even tried, unsuccessfully, to obtain Radical-Socialist backing for the regional Senate seat.

Nor did he allow his work for peace to languish. A partisan of a peaceful détente between France and Germany, he made a speaking tour of Germany to encourage reconciliation between the two countries. And the proceeds of the Nobel Peace Prize he donated to various pacifist programs.

At the age of ninety-one, Buisson died of heart disease at his home in Thieuloy-Saint-Antone, survived by two sons and a daughter.

| Selected Bibliography |

| Basch, Victor, «Ferdinand Buisson», in Les Cahiers des droits de l’homme (January 20, 1925). |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, Le Christianisme libéral. Paris, Cherbuliez, 1865. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, Le Colonel Picquart en prison: Discours prononcé le 10 mai 1899. Paris, Ollendorff, 1899. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, La Constitution immédiate de la Société des Nations. Paris, Ligue, des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, [1908]. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, éd., Diaionnaire de pédagogie et d’instruction primaire. 4 Tomes. Paris, Hachette, 1878-1887. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, La Foi laïque: Extraits de discours et d’écrits, 1878-1911. Paris, Hachette, 1912. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, La Politique radicale: Étude sur les doctrines du parti radical et radical-socialiste. Paris, Giard et Brière, 1908. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, Rapport sur l’instruction primaire à l’Exposition universelle de Philadelphie en 1876. Paris, Impr. nationale, 1878. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, Rapport sur l’instruction primaire à l’Exposition universelle de Vienne en 1873. Paris, Impr. rationale, 1875. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, La Réligion, la morale et la science, et leur conflit dans l’éducation contemporaine: Quatre conférences faites à l’aula de l’Université de Genève (avril, 1900). Paris, Fischbacher, 1900. |

| Buisson, Ferdinand, and Frederic E. Farrington, eds., French Educational Ideals of Today: An Anthology of the Molders of French Educational Thought of the Present. Yonkers-on-Hudson, N.Y., World, 1919. |

| Talbott, John E., The Politics of Educational Reform in France, 1918-1940. Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1969. |

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Ferdinand Buisson – Facts

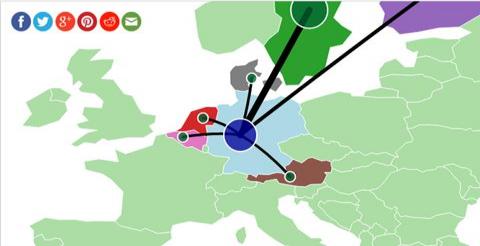

Ludwig Quidde – Nominations

The Nobel Peace Prize 1927

Ferdinand Buisson, Ludwig Quidde

Nominated on 37 occasions for the Nobel Prize in

- Peace 1924, by Alexius Björkman, Erik Röing, N Norling

- Peace 1925, by Helene Stöcker

- Peace 1925, by A Grotenfeld, O Mantere, V Voionmaa

- Peace 1925, by H. Ch. G. van der Mandere

- Peace 1925, by Hellmut von Gerlach

- Peace 1925, by Axel Theodor Adelswärd

- Peace 1925, by Hans Wehberg

- Peace 1925, by Hellmut von Gerlach

- Peace 1925, by Arthur Müller

- Peace 1925, by N Nilsson

- Peace 1925, by A Grotenfeld

- Peace 1925, by Axel Theodor Adelswärd

- Peace 1925, by Walther Adrian Schücking

- Peace 1925, by H. Ch. G. van der Mandere

- Peace 1925, by Adolf Heilberg

- Peace 1925, by Henri Marie La Fontaine

- Peace 1925, by Axel Theodor Adelswärd

- Peace 1926, by Aage Friis

- Peace 1926, by Adolf Heilberg

- Peace 1926, by Henri Marie La Fontaine

- Peace 1926, by Löbe

- Peace 1926, by Arthur Müller

- Peace 1926, by Hans Wehberg

- Peace 1926, by Baron Eduard de Neufville

- Peace 1926, by The Swedish Inter-Parliamentary Group (Axel Theodor Adelswärd)

- Peace 1926, by Arthur Müller

- Peace 1926, by Baron Eduard de Neufville

- Peace 1926, by The Swedish Inter-Parliamentary Group (Axel Theodor Adelswärd)

- Peace 1927, by 41 members of the Swedish Inter-Parliamentary Group

- Peace 1927, by Aage Friis

- Peace 1927, by Hans Wehberg

- Peace 1927, by Henri Marie La Fontaine

- Peace 1927, by Adolf Heilberg

- Peace 1927, by 41 members of the Swedish Inter-Parliamentary Group

- Peace 1927, by Axel Theodor Adelswärd, Eric Hallin

- Peace 1927, by Hans Wehberg

- Peace 1927, by Axel Theodor Adelswärd

Submitted 22 nominations, for the Nobel Prize in

- Literature 1930, nominee: Manfred Kyber

- Peace 1908, nominee: The Permanent International Peace Bureau

- Peace 1911, nominee: Felix Stone Moscheles, Adolf Richter

- Peace 1911, nominee: Adolf Richter, Felix Stone Moscheles

- Peace 1913, nominee: Felix Stone Moscheles, Adolf Richter

- Peace 1913, nominee: Adolf Richter, Felix Stone Moscheles

- Peace 1913, nominee: Adolf Richter

- Peace 1922, nominee: Friedrich Wilhelm Förster, Benjamin de Jong van Beek en Donk

- Peace 1922, nominee: Benjamin de Jong van Beek en Donk, Friedrich Wilhelm Förster

- Peace 1922, nominee: The National Peace Council

- Peace 1928, nominee: Jane Addams

- Peace 1928, nominee: Tomás Garrigue Masaryk

- Peace 1930, nominee: Jane Addams

- Peace 1931, nominee: Jane Addams, The Permanent International Peace Bureau

- Peace 1931, nominee: The Permanent International Peace Bureau, Jane Addams

- Peace 1933, nominee: Walther Adrian Schücking

- Peace 1933, nominee: The Permanent International Peace Bureau

- Peace 1935, nominee: Friedrich Heinrich Christoph Küster, Carl von Ossietzky

- Peace 1935, nominee: Carl von Ossietzky, Friedrich Heinrich Christoph Küster

- Peace 1937, nominee: Comité de Secours aux pacifistes exilés

- Peace 1938, nominee: Comité de Secours aux pacifistes exilés

- Peace 1939, nominee: Comité de Secours aux pacifistes exilés

Explore a visualization of the nominations

Search for nominees and nominators in the Nomination Archive

MLA style: “Ludwig Quidde – Nominations”. Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 22 Jun 2018.

Overrekkelsestale

Norwegian

| English |

© THE NOBEL FOUNDATION 2012

General permission is granted for the publication in newspapers in any language. Publication in periodicals or books, or in digital or electronic forms, otherwise than in summary, requires the consent of the Foundation. On all publications in full or in major parts the above underlined copyright notice must be applied.

Overrekkelsestale av leder av Den Norske Nobelkomite Thorbjørn Jagland, Oslo, 10. desember, 2012

Deres Majesteter, Deres Kongelige Høyheter, statsoverhoder, regjeringssjefer, eksellenser, mine damer og herrer,

Ærede ledere for Den europeiske union,

Midt i en vanskelig tid for Europa har Den Norske Nobelkomite villet minne om hva Den europeiske union betyr for freden i Europa.

Etter de to verdenskrigene i forrige århundre måtte verden bevege seg bort fra nasjonalisme og gå i retning av internasjonalt samarbeid. De forente nasjoner ble dannet. Verdenserklæringen om menneskerettigheter ble vedtatt.

For Europa, som hadde vært utgangspunktet for de to krigene, måtte den nye internasjonalismen være bindende og forpliktende. Den måtte bygge på menneskerettigheter, demokrati og rettsstatlige prinsipper som kunne håndheves. Og på et økonomisk samarbeid med det mål å gjøre landene til likeverdige partnere på den europeiske markedsplassen. Således skulle landene bindes sammen for å gjøre nye kriger umulig.

Kull- og stålunionen av 1951 ble starten på en forsoningsprosess som har pågått helt fram til i dag. Først i den vestlige delen av Europa, men prosessen fortsatte over øst-vestskillet da Berlin-muren falt og har nå nådd til et Balkan der det var blodige kriger for mindre enn 15-20 år siden.

EU har hele tiden vært en sentral drivkraft i disse forsoningsprosessene.

EU har faktisk virket både til den «folkenes forbrødring» og «den fremme av fredskongresser» som Alfred Nobel skrev om i sitt testamente.

Derfor er Nobels Fredspris fortjent og nødvendig. Vi gratulerer.

I lys av finanskrisen som rammer så mange uskyldige mennesker, ser vi at det politiske rammeverk som Unionen forankres i, er viktigere enn noensinne. Vi må stå sammen. Vi har et kollektivt ansvar. Uten det europeiske samarbeidet ville resultatet lett ha blitt ny proteksjonisme, ny nasjonalisme med fare for at det som er vunnet, går tapt.

Vi vet fra mellomkrigstiden at dette kan skje når vanlige mennesker betaler regningen for en finanskrise andre har utløst. Men løsningen er nå som da ikke at landene handler på egen hånd på bekostning av andre. Heller ikke at utsatte minoriteter får skylden.

Da går vi i gårsdagens feller.

Europa må bevege seg fremover.

Ta vare på det som er vunnet.

Og forbedre det som er skapt, slik at vi kan løse de problemene som truer det europeiske fellesskapet i dag.

Bare slik kan vi løse til alles beste de problemer finanskrisen har skapt.

I 1926 ga Den Norske Nobelkomite fredsprisen til Frankrike og Tysklands utenriksministre Aristide Briand og Gustav Stresemann, året etter til Ferdinand Buisson og Ludwig Quidde, alle for dere forsøk på å fremme tysk-fransk forsoning.

På 1930-tallet gikk forsoningen over i konflikt og krig.

Etter andre verdenskrig la forsoningen mellom Tyskland og Frankrike selve grunnlaget for europeisk integrasjon. De to land hadde ført tre store kriger i løpet av 70 år, den tysk-franske krig i 1870-71, den første og den andre verdenskrig.

I de første år etter 1945 var fristelsen stor til å fortsette i samme spor, med vekt på revansj og konflikt. Så lanserte den franske utenriksminister Robert Schuman planene for en kull- og stålunion 9. mai 1950.

Regjeringene i Paris og i Bonn bestemte seg for å gi historien et helt annet løp ved å legge kull – og stålproduksjonen under en felles myndighet. De sentrale elementer i rustningsproduksjonen skulle utgjøre bærebjelkene i en fredens konstruksjon.

Økonomisk samarbeid skulle nå forhindre nye kriger og konflikter i Europa slik Schuman formulerte det i talen av 9. mai: «The solidarity in production thus established will make it plain that any war between France and Germany becomes not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible.”

Forsoningen mellom Tyskland og Frankrike er antakelig det mest dramatiske eksempel vi kjenner fra historien på at krig og konflikt raskt kan snues til fred og samarbeid.

Det at Tysklands Forbundskansler Angela Merkel og Frankrikes President Francois Hollande er til stede her i dag, gjør denne dagen spesielt symbolsk.

Neste skritt etter Kull – og Stålunionen var undertegningen av Romatraktaten 25. mars 1957. Nå ble de fire friheter slått fast. Grensene skulle åpnes og hele økonomien, ikke bare kull-og stålindustrien veves sammen. De seks statslederne i Tyskland, Frankrike, Italia, Nederland, Belgia og Luxembourg skrev at de «by thus pooling their resources to preserve and strengthen peace and liberty, and calling upon the other peoples of Europe who share their ideal to join in their efforts, have decided to create a European Economic Community …”

I 1973 bestemte Storbritannia, Irland og Danmark seg for å svare på denne oppfordringen.

I 1981 kom Hellas med, Spania og Portugal i 1986. Medlemskap i EEC og EU var en rett for alle europeiske land «whose system of government is founded on the principles of democracy» og som aksepterer betingelsene for medlemskap. Medlemskapet konsoliderte demokratiet i disse landene ikke minst gjennom de generøse støtteordninger som Hellas, Portugal og Spania kunne nyte godt av.

Neste skritt framover kom da Berlinmuren falt i løpet av et mirakuløst halvår i 1989. Det åpnet seg da muligheter for at de nøytrale landene Sverige, Finland og Østerrike kunne bli medlem.

Men også de nye demokratiene ønsket å bli en del av Vesten militært, økonomisk og kulturelt. I denne sammenheng var medlemskap i EU et selvfølgelig mål. Og et middel slik at overgangen til demokrati kunne gå så smertefritt som mulig. Overlatt til seg selv kunne ingen være sikker på hvordan utviklingen ville bli.

For det har historien lært oss: Frihet koster.

Forskjellen på det som skjedde etter Berlin-murens fall og det som nå skjer i landene i den arabiske verden er iøynefallende. De øst-europeiske landene kunne raskt bli med i et europeisk verdifellesskap, komme med i et stort marked og nyte godt av økonomisk støtte. De nye demokratiene i Europas nabolag har ikke en slik trygg havn å søke til. Overgangen til demokrati ser da også ut til å bli lang og smertefull og har allerede utløst krig og konflikt.

I Europa ble skillet mellom øst og vest brutt ned raskere enn noen kunne tenkt seg. Demokratiet er styrket i en region hvor de demokratiske tradisjoner var meget begrensete; de mange etnisk-nasjonale spørsmål som hadde ridd regionen som en mare, er praktisk talt bilagt.

Mikhail Gorbatsjov skapte de ytre forutsetninger for Øst-Europas frigjøring, nasjonale ledere med Lech Wałęsa i spissen tok de nødvendige lokale initiativ. Både Wałęsa og Gorbatsjov fikk sine vel fortjente fredspriser.

Nå får endelig EU sin. Det som skjedde i disse månedene og årene etter Berlin-murens fall er kanskje den største solidaritetshandling noensinne på det europeiske kontinent.

Dette kollektive løftet kunne ikke ha skjedd uten EUs politiske og økonomiske tyngde.

Vi må på denne dag også hedre Forbundsrepublikken Tyskland og dens leder Helmut Kohl for at han tok ansvaret og de enorme kostnader på vegne av Forbundsrepublikkens innbyggere ved nesten over natten å inkludere Øst-Tyskland i et forent Tyskland.

Men alt var likevel ikke ordnet. Med kommunismens fall gjenoppstod et gammelt problem: Balkan. Titos autoritære styre hadde holdt de mange etniske konfliktene under lokk. Men når dette lokket ble tatt av, blusset voldelige konflikter opp som vi aldri trodde vi ville se igjen i det frie Europa.

Det ble faktisk utkjempet fem kriger i løpet av få år. Vi glemmer aldri Srebrenica, hvor 8000 muslimer ble slaktet ned i løpet av en dag.

Nå forsøker imidlertid EU å legge grunnlaget for fred også på Balkan. Slovenia kom med i EU i 2004. Kroatia vil bli medlem i 2013. Montenegro har startet forhandlinger om medlemskap og Serbia og Den tidligere jugoslaviske republikken Makedonia er gitt kandidatstatus.

Balkan var og er et komplisert område. Fortsatt er det uløste konflikter. Det er nok å nevne at Kosovos status ennå ikke er fullt ut avklart. Bosnia-Herzegovina er en stat som knapt fungerer på grunn av den vetoretten de tre folkegruppene er gitt mot hverandre.

Den overordnete løsningen er at den samme integrasjonsprosessen som man har hatt i det øvrige Europa, føres videre. Grensene blir mindre absolutte; hvilken folkegruppe man tilhører er ikke lenger avgjørende for ens sikkerhet.

EU må derfor spille en hovedrolle også her for å skape ikke bare våpentilstand, men reell fred.

I flere tiår har Tyrkia diskutert sitt forhold til EU og EU sitt til Tyrkia. Etter at det nye lederskapet med AKP-partiet i spissen vant et klart flertall i parlamentet, har målet om medlemskap i EU vært førende for reformprosessen i Tyrkia. Det kan ikke være tvil om at dette har bidratt til å styrke den demokratiske utvikling i landet. Dette nyter Europa godt av, men suksess her er også viktig for utviklingen i Midtøsten.

Den Norske Nobelkomite har gang på gang delt ut Fredsprisen til menneskerettighetsforkjempere. Nå går prisen til en organisasjon som man ikke kan bli medlem av uten først å ha tilpasset all sin lovgivning til Den universelle menneskerettighetserklæringen og Europakonvensjonen om menneskerettigheter.

Men menneskerettigheter er ikke i seg selv nok. Vi ser det nå som land etter land opplever alvorlig sosial uro fordi feilslått politikk, korrupsjon og skatteunndragelser har sendt pengene ned i store svarte hull.

Det er forståelig at dette fører til protester. Demonstrasjoner er en del av demokratiet. Politikkens oppgave er å omgjøre protestene til konkret politisk handling.

Veien ut av uføret er ikke å demontere de europeiske institusjonene.

Vi må opprettholde solidaritet over grensene, som Unionen gjør gjennom gjeldslette og andre konkrete støttetiltak og ved å lage rammer for en finansnæring som vi alle er avhengige av. Utro tjenere må fjernes. Dette er forutsetninger for at massene i Europa fortsatt skal tro på kompromissene og moderasjonen Unionen nå avkrever dem.

Deres Majesteter, Deres Kongelige Høyheter, regjeringssjefer og statsoverhoder, mine damer og herrer, ærede ledere for Den europeiske union,

Jean Monnet sa at «ingenting kan oppnås uten mennesker, men ingenting blir varig uten institusjoner.»

Vi er ikke samlet her i dag i troen på at EU er perfekt. Vi er samlet i troen på at vi her i Europa må løse problemene i fellesskap. Til det trenger vi institusjoner som kan inngå de nødvendige kompromisser. Vi trenger institusjoner for å sikre at både nasjonalstater og individer utøver selvkontroll og moderasjon. I en verden med så mange farer er kompromiss, selvkontroll og moderasjon det 21. århundres fremste nødvendigheter.

80 millioner måtte betale prisen for at ekstremismen fikk utfolde seg.

Vi må sammen sørge for at vi ikke taper det vi har bygget på ruinene av de to krigene.

Det er egentlig fantastisk hva dette kontinentet har oppnådd, fra å være et krigens til å bli et fredens kontinent. I denne prosessen har Den europeiske union vært en uhyre sentral aktør. Derfor fortjener den Nobels Fredspris.

Freskene på veggene her i Oslo Rådhus er inspirert av Ambrogio Lorenzettis 1300-tallsfresker i kommunehuset i Siena som har navnet “Allegory of the effects of good government.” Fresken viser en levende middelalderby med portene i bymuren tillitsfullt på vidt gap foran livlige mennesker som sanker grøden inn fra bugnende marker. Men Lorenzetti malte et bilde til: “Allegory of the effects of bad government.” Det viser et oppløst, lukket og pestherjet Siena ødelagt av maktkamp og krig.

De to bildene skal minne oss om at det er opp til oss selv om vi skal leve under ordnede forhold eller ikke.

La det gode styre seire i Europa. Vi er nødt til å leve sammen på dette kontinentet.

Living together

Vivre ensemble

Zusammenleben

Convivencia Birlikte

Yasamak

Git’vemeste

Leve sammen

Gratulerer Europa. Til slutt bestemte vi oss for å leve sammen.

Måtte andre kontinenter følge etter.

Takk for oppmerksomhet

Award ceremony speech

| English |

General permission is granted for the publication in newspapers in any language. Publication in periodicals or books, or in digital or electronic forms, otherwise than in summary, requires the consent of the Foundation. On all publications in full or in major parts the above underlined copyright notice must be applied.

Presentation Speech by Thorbjørn Jagland, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Oslo, 10 December 2012.

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Heads of State, Heads of Government, Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen,

Honourable Presidents of the European Union,

At a time when Europe is undergoing great difficulties, the Norwegian Nobel Committee has sought to call to mind what the European Union means for peace in Europe.

After the two world wars in the last century, the world had to turn away from nationalism and move in the direction of international cooperation. The United Nations were formed. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted.

For Europe, where both world wars had broken out, the new internationalism had to be a binding commitment. It had to build on human rights, democracy, and enforceable principles of the rule of law. And on economic cooperation aimed at making the countries equal partners in the European marketplace. By these means the countries would be bound together so as to make new wars impossible.

The Coal and Steel Community of 1951 marked the start of a process of reconciliation which has continued right to the present day. Beginning in Western Europe, the process continued across the east-west divide when the Berlin Wall fell, and has currently reached the Balkans, where there were bloody wars less than 15 to 20 years ago.

The EU has constantly been a central driving force throughout these processes of reconciliation.

The EU has in fact helped to bring about both the “fraternity between nations” and the “promotion of peace congresses” of which Alfred Nobel wrote in his will.

The Nobel Peace Prize is therefore both deserved and necessary. We offer our congratulations.

In the light of the financial crisis that is affecting so many innocent people, we can see that the political framework in which the Union is rooted is more important now than ever. We must stand together. We have collective responsibility. Without this European cooperation, the result might easily have been new protectionism, new nationalism, with the risk that the ground gained would be lost.

We know from the inter-war years that this is what can happen when ordinary people pay the bills for a financial crisis triggered by others. But the solution now as then is not for the countries to act on their own at the expense of others. Nor for vulnerable minorities to be given the blame.

That would lead us into yesterday’s traps.

Europe needs to move forward.

Safeguard what has been gained.

And improve what has been created, enabling us to solve the problems threatening the European community today.

This is the only way to solve the problems created by the financial crisis, to everyone’s benefit.

In 1926, the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded the Peace Prize to the Foreign Ministers of France and Germany, Aristide Briand and Gustav Stresemann, and the following year to Ferdinand Buisson and Ludwig Quidde, all for their efforts to advance Franco-German reconciliation.

In the 1930s the reconciliation degenerated into conflict and war.

After the Second World War, the reconciliation between Germany and France laid the very foundations for European integration. The two countries had waged three wars in the space of 70 years: the Franco-Prussian war in 1870-71, then the First and Second World Wars.

In the first years after 1945, it was very tempting to continue along the same track, emphasizing revenge and conflict. Then, on the 9th of May 1950, the French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman presented the plans for a Coal and Steel Community.

The governments in Paris and Bonn decided to set history on a completely different course by placing the production of coal and steel under a joint authority. The principal elements of armaments production were to form the beams of a structure for peace. Economic cooperation would from then on prevent new wars and conflicts in Europe, as Schuman put it in his 9th of May speech: “The solidarity in production thus established will make it plain that any war between France and Germany becomes not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible”.

The reconciliation between Germany and France is probably the most dramatic example in history to show that war and conflict can be turned so rapidly into peace and cooperation.

The presence here today of German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President François Hollande makes this day particularly symbolic.

The next step after the Coal and Steel Community was the signing of the Treaty of Rome on the 25th of March 1957. The four freedoms were now established. Borders were to be opened, and the whole economy, not just the coal and steel industry, was to be woven into a whole. The six heads of state, of Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg, wrote that they “by thus pooling their resources to preserve and strengthen peace and liberty, and calling upon the other peoples of Europe who share their ideal to join in their efforts, have decided to create a European Economic Community …”.

In 1973, Great Britain, Ireland and Denmark decided to respond to this call.

Greece joined in 1981, and Spain and Portugal in 1986. Membership of the EEC and EU was the right of all European countries “whose system of government is founded on the principles of democracy” and who accept the conditions for membership. Membership consolidated democracy in these countries, not least through the generous support schemes from which Greece, Portugal and Spain were able to benefit.

The next step forward came when the Berlin Wall fell in the course of a miraculous half year in 1989. Opportunities opened up for the neutral countries Sweden, Finland and Austria to become members.

But the new democracies, too, wished to become parts of the West, militarily, economically and culturally. In that connection membership of the EU was a self-evident objective. And a means, enabling the transition to democracy to be made as painlessly as possible. If they were left to themselves, nobody could be certain how things would turn out.

For history has taught us: freedom comes at a price.

The difference is very marked between what happened after the fall of the Berlin Wall and what is now happening in the countries of the Arab world. The Eastern European countries were quickly able to participate in a European community of values, join in a large market, and benefit from economic support. The new democracies in the vicinity of Europe have no such safe haven to make for. The transition to democracy also looks like being long and painful and has already triggered war and conflict.

In Europe the division between east and west was broken down more quickly than anyone could have anticipated. Democracy has been strengthened in a region where democratic traditions were very limited; the many disputes over ethnicity and nationality that had so troubled the region have largely been settled.

Mikhail Gorbachev created the external conditions for the emancipation of Eastern Europe, and national leaders headed by Lech Wałęsa took the necessary local initiatives. Both Wałęsa and Gorbachev received their well-deserved Peace Prizes.

Now at last it is the EU’s turn. Events during the months and years following the fall of the Berlin Wall may have amounted to the greatest act of solidarity ever on the European continent.

This collective effort could not have come about without the political and economic weight of the EU behind it.

On this day we must also pay tribute to the Federal Republic of Germany and its Chancellor Helmut Kohl for assuming responsibility and accepting the enormous costs on behalf of the inhabitants of the Federal Republic when East Germany was included practically overnight in a united Germany.

Not everything was settled yet, however. With the fall of communism an old problem returned: the Balkans. Tito’s authoritarian rule had kept a lid on the many ethnic conflicts. When that lid was lifted, violent conflicts blazed up again the like of which we had thought we would never see again in a free Europe.

Five wars were in fact fought in the space of a few years. We will never forget Srebrenica, where 8,000 Muslims were massacred in a single day.

Now, however, the EU is seeking to lay the foundations for peace also in the Balkans. Slovenia joined the EU in 2004. Croatia will become a member in 2013. Montenegro has opened membership negotiations, and Serbia and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia have been given candidate status.

The Balkans were and are a complicated region. Unresolved conflicts remain. Suffice it to mention that the status of Kosovo is still not finally settled. Bosnia-Hercegovina is a state that hardly functions owing to the veto the three population groups have become entitled to exercise against each other.

The paramount solution is to extend the process of integration that has applied in the rest of Europe. Borders become less absolute; which population group one belongs to no longer determines one’s security.

The EU must accordingly play a main part here, too, to bring about not only an armistice but real peace.

For several decades Turkey and the EU have been discussing their relations to each other. After the new government, headed by the AKP party, won a clear parliamentary majority, the aim of EU membership has provided a guideline for the process of reform in Turkey. There can be no doubt that this has contributed to strengthening the development of democracy there. This benefits Europe, but success in this respect is also important to developments in the Middle East.

The Norwegian Nobel Committee has time and again presented the Peace Prize to champions of human rights. Now the prize is going to an organization of which one cannot become a member without first having adapted all one’s legislation to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights.

But human rights as such are not enough. We can see this now that country after country is undergoing serious social unrest because misplaced policies, corruption and tax evasion have led to money being poured into gaping black holes.

This leads, understandably, to protests. Demonstrations are part of democracy. The task of politics is to transform the protests into concrete political action.

The way out of the difficulties is not to dismantle the European institutions.

We need to maintain solidarity across borders, as the Union is doing by cancelling debts and adopting other concrete support measures, and by formulating the framework for a finance industry on which we all depend. Unfaithful servants must be removed. These are preconditions for the continuing belief of the European masses in the compromises and moderation which the Union is now demanding of them.

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Heads of Government and Heads of State, ladies and gentlemen, Honourable Presidents of the European Union,

Jean Monnet said that “nothing can be achieved without people, but nothing becomes permanent without institutions”.

We are not gathered here today in the belief that the EU is perfect. We are gathered in the belief that here in Europe we must solve our problems together. For that purpose we need institutions that can enter into the necessary compromises. We need institutions to ensure that both nation-states and individuals exercise self-control and moderation. In a world of so many dangers, compromise, self-control and moderation are the principal needs of the 21st century.

80 million people had to pay the price for the exercise of extremism.

Together we must ensure that we do not lose what we have built on the ruins of the two world wars.

What this continent has achieved is truly fantastic, from being a continent of war to becoming a continent of peace. In this process the European Union has figured most prominently. It therefore deserves the Nobel Peace Prize.

The frescos on the walls here in the Oslo City Hall are inspired by Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s frescos from the 1300s in the Siena town hall, named “Allegory of the effects of good government”. The fresco shows a living medieval town, with the gates in the wall invitingly wide open to spirited people bringing the harvest in from fruitful fields. But Lorenzetti painted another picture: “Allegory of the effects of bad government”. It shows Siena in chaos, closed and ravaged by the plague, destroyed by a struggle for power and war.

The two pictures are meant to remind us that it is up to ourselves whether or not we are to live in well-ordered circumstances.

May good government win in Europe. We are bound to live together on this continent.

Living together

Vivre ensemble

Zusammenleben

Convivencia Birlikte

Yasamak

Git’vemeste

Leve sammen

Congratulations to Europe. In the end we decided to live together.

May other continents follow.

Thank you for your attention.

Award ceremony speech

Presentation Speech by Fredrik Stang*, Chairman of the Nobel Committee, on December 10, 1927

The Nobel Committee has awarded the Peace Prize for this year jointly to Ferdinand Buisson and Ludwig Quidde.

At last year’s ceremony the Committee gave prominence to three events of historical significance to the world: the Dawes Plan, the Locarno Pact, and Germany’s admission to the League of Nations. These were political measures effected by responsible agents of government, and we emphasized their importance by awarding the Peace Prize to four statesmen1 who had rendered outstanding service in making them possible.

This year we pay tribute through the Nobel Prize to a different kind of work for the cause of peace. Governments and their policies are not the only potential menace to peace. A constant and real threat of war also lies in the mentality of men, in the psychology of the masses. Therefore the great organized work for peace must be preceded by the education of the people, by a campaign to turn mass thinking away from war as a recognized means of settling disputes, and to substitute another and much higher ideal: peaceful cooperation between nations, with an international court of justice to resolve any disagreements which might arise between them. It is in the task of reorienting public opinion that Buisson and Quidde have played such prominent roles. They have guided this work in two countries where it has been particularly difficult to accomplish, but where the need for it has been commensurately great. In presenting the Nobel Peace Prize to Buisson and Quidde, the Nobel Committee wishes to recognize the emergence in France and Germany of a public opinion which favors peaceful international cooperation. It is this happy circumstance which brought about the rapprochement between Germany and France, which in turn found expression in the events rewarded at last year’s award ceremony.

Ferdinand Buisson was born in Paris in 1841. He studied philosophy and pedagogy but was later unable to obtain a position in France because he refused to take the oath to the Emperor2. He therefore went to Switzerland where he stayed from 1866 to 1870. Upon his return to France in the autumn of 1870 he held various educational posts and in 1879 was appointed, director of the primary school section of the Ministry of Public Instruction. In this capacity he was actively concerned in the drafting and implementing of the laws on free, compulsory, and nondenominational primary education in France. In 1897 he became professor of education at the Sorbonne.

The Dreyfus case3 brought Buisson into politics. He threw himself heart and soul into the struggle waged on behalf of this unjustly convicted man. He joined the French League of the Rights of Man, which, inspired by Zola’s J’accuse4, was founded at the time of the Dreyfus affair. The aim of this society was to attack every form of injustice and oppression both in France and elsewhere. As a member of the Radical-Socialist Party, Buisson was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1902. Although defeated in 1914, he returned to the Chamber in 1919, holding his seat until 1924.

The cause of peace first attracted Buisson when he was still a young man. He took part in the first congress of the Ligue de la paix et de la liberté5 [League of Peace and Liberty] in 1867 and wrote articles denouncing militarism and insisting that intensive education of the masses was the way to put an end to war.

When the World War came, Buisson did not protest it. Regarding France as the attacked party, he believed that a German victory would mean defeat for justice and the principle of international solidarity. During the early years of the war the League also remained passive. The essential thing, said Buisson, was to win in order to put an end not only to this war, but to all wars. Convinced that the Allies would win in the end, he was greatly concerned that they should not misuse their victory but should take action to lay the foundations for a new, international world by creating a League of Nations. From 1916 on he worked tirelessly for a just peace and supported Wilson‘s program.

The peace turned out to be a bitter disappointment for Buisson. In an open letter published on May 23, 1919, he criticized the League of Nations as it had been structured, and described it as a league of the victorious powers of the Entente. It was nevertheless a fait accompli; it must be defended. It was therefore necessary to put propaganda to work, with a view to shaping the League into an efficient instrument for the prevention of war and for the promotion of international solidarity. In a eulogy on Wilson in 1924 he expressed his belief that the League would grow, that the day would come when it would be a force claiming the respect of the whole world, even of those who then dismissed it with a smile. And he preached the disarmament of hatred, for this must precede the disarmament of nations.

Buisson and his friends have not confined themselves merely to talking about the disarmament of hatred; they have sought to make it a living fact. At the time of the Ruhr dispute6 they had the courage to try to build a bridge by inviting German friends of peace to Paris and then returning the visit to do what they could in Germany. Buisson, at the age of eighty-four, accompanied the delegation. Speaking on a number of occasions, he concluded one address to the German people with these words:

«A force exists which is far greater than France, far greater than Germany, far greater than any nation, and that is mankind. But above mankind itself stands justice, which finds its most perfect expression in human brotherhood.»

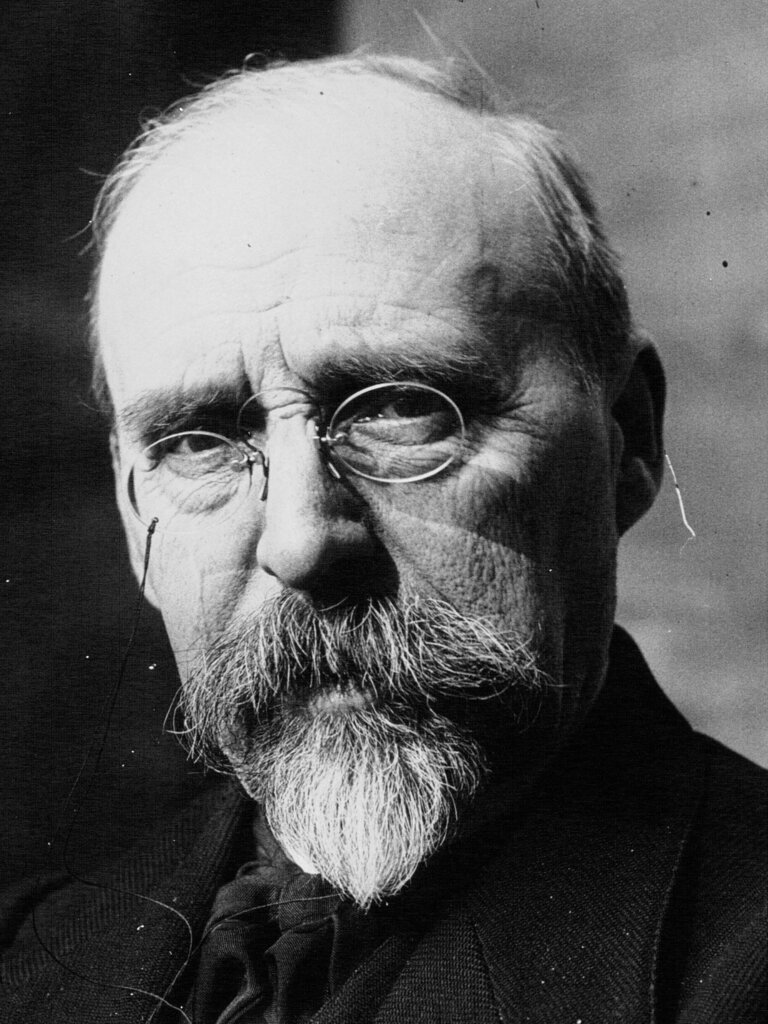

Ludwig Quidde was born in Bremen in 1858. He studied at Strasbourg and Göttingen, his main interest being the history of Germany in the Middle Ages. After taking his doctorate, he devoted some years to historical writing and publishing. This pursuit took him to Rome for a few years as a staff member of the Prussian Historical Institute there. Following his return to Germany, he threw himself into political activity and especially into work for peace. Being of independent means, he had no need to find paid employment and was therefore in a position to devote his undivided efforts to his chosen interests.

While he was in Rome, Quidde wrote Caligula (1894), a small pamphlet of some sixteen pages. Ostensibly an historically accurate description of the emperor Caligula7 and the mad obsessions from which he suffered, it was actually a rather transparent satire on Emperor Wilhelm II8. The book created a storm. It had an enormous sale, reputedly reaching a printing of several hundred thousand copies. Many people were naturally delighted with it. But in others it aroused bitter resentment, and for years afterwards Quidde was to learn in various ways how deeply the wound had been felt.

Quidde’s work for peace began about the time Caligula appeared. Ever since then he has worked ceaselessly as lecturer and organizer. He has taken part in, and in many cases presided over, numerous peace congresses; he has attended conferences of the Interparliamentary Union9; and he has written countless publications, some of which treated current problems so trenchantly as to lead to their confiscation and even to the institution of legal proceedings against their author.

For Quidde the outbreak of war heralded a period of intensive and diversified activity. He went immediately to The Hague, thinking that from neutral Holland he would be able to keep alive his connections with the French, English, and Belgian pacifists. In this he was disappointed. And so he returned to Germany but tried even from there to sway public opinion in the other belligerent countries.

His work was divided between organization and writing. The war and all the problems it raised led to friction within the pacifist camp in Germany, impeded organizational operations, and made great demands on Quidde’s ability as a mediator. However, he succeeded not only in holding the movement together, but also in increasing support for the peace organizations. All this work left Quidde little time to write. Of the things he published during and after the war I should like to mention two which seem to me to be characteristic of his views and of his manner of working.

In 1915 he published a pamphlet entitled Sollen wir annektieren? [Should We Annex?]. In this pamphlet he mounts an attack on the desire for annexation which at that stage of the war found wide support in Germany. To him it was sheer lunacy to try to secure the peace by destroying the antagonist. In this publication he takes no marked political standpoint but sets out in a calm, well-balanced, and pertinently documented argument the political, economic, and cultural consequences of a peace based on annexation. He himself submits a positive program for peace, whose chief point is that the freedom of the seas and the Open Door policy10 should be secured through the peace settlement. The pamphlet was confiscated. A revised edition met the same fate, but this did not prevent it and a French translation of it from reaching a wide public.

When the question of guilt arose at the end of the war, Quidde entered the discussion with his pamphlet Die Schuldfrage [The Question of Responsibility]11. Once again his subject is calmly reasoned. He goes to the root of the question, distinguishing between responsibility for creating the circumstances which paved the way for the World War and responsibility for the actions which unleashed war at the decisive moment. He does not share the view of those members of the German pacifist movement who lay all the blame at Germany’s door, and, as one might expect, he is even less inclined to the other extreme. Calmly and without passion he draws the distinction between responsibility and guilt, analyzing the interrelationship of the many factors involved.

Two qualities stand out in Quidde’s writing and in his work as a whole: moderation and courage. Although he has never had a chance to publish major works outside his professional field of history, all of his work beats the stamp of the historian and the scholar. And he has displayed his courage on many occasions. His own account of the origins of Caligula and of the events associated with it is characteristic of the man. As already mentioned, the book appears on the face of it to be an objective portrayal of the Roman emperor’s life and character. In order to make sure that it was historically accurate and that it had been in no way colored by the political purpose behind it, he had the manuscript read by several scholars specializing in Roman history. When he decided to print the pamphlet, his friends advised him to do so in Switzerland and to publish it anonymously. But he had it printed in Germany under his own name. After the pamphlet’s appearance when everyone expected him to be prosecuted, his friends advised him to flee to Switzerland. But he stood fast and remained in his own country. My impression is that Quidde’s later writings are also imbued with the same devotion to the truth, and their publication has on occasion demanded no less courage.

Today the Nobel Committee honors two admirable and distinguished servants of peace. We thank them for their long and tireless efforts in the cause of peace. To work for the cause of peace is to clear a path for honest and just relations between peoples, for recognition of the intrinsic worth of human beings and of the equal right of all people to live here on earth, and for the success of the greatest political idea ever conceived: the supplanting of war by peace.

* Mr. Stang, also at this time professor of jurisprudence at the University of Oslo, delivered this speech on December 10, 1927, in the auditorium of the Nobel Institute in Oslo. The two laureates who shared the prize, Mr. Buisson and Mr. Quidde, were present to accept the medals and diplomas, each doing so with a brief speech of thanks. Les Prix Nobel en 1927 carries a report in French of Mr. Stang’s speech. The translation given here is based on a typescript of the text in Norwegian deposited in the files of the Nobel Institute

1. Charles G. Dawes, co-recipient for 1925; Austen Chamberlain, co-recipient for 1925; Aristide Briand, co-recipient for 1926; Gustav Stresemann, co-recipient for 1926.

2. Louis Napoleon Bonaparte (1808-1873), Napoleon III, emperor of the French (1852-1870).

3. The Dreyfus case began in 1894 when Captain Alfred Dreyfus (1859-1935), a Jewish Alsatian in the French army, was convicted of having promised to deliver secret French documents to Major Schwartzkoppen, German military attaché in Paris. When evidence pointing toward Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy as the real traitor was brought forward several times in succeeding years and silenced, the case became a major political issue throughout France. In 1906 Dreyfus was cleared and reinstated as a major; his innocence was proved conclusively in 1930 upon publication of the Schwartzkoppen papers.

4. Émile Zola (1840-1902), French novelist and vigorous Dreyfusard whose J’accuse (1898) openly and violently denounced everyone who had a decisive part in the case against Dreyfus.

5. The Ligue internationale de la paix et de la liberté was founded by Charles Lemonnier in Geneva in 1867.

6. After the Reparation Commission declared Germany in default on deliveries of timber and coal, French and Belgian troops occupied Germany’s industrial Ruhr district early in 1923. The German government suspended deliveries and supported the area’s population in a policy of passive resistance, which met with reprisals from the occupying authorities. The Dawes Plan led to the departure of the last French and Belgian soldiers from the Ruhr on July 31, 1925.

7. Caligula (A.D. 12-A.D. 41), Roman emperor (A.D. 37-A.D. 41), known for his irrational cruelty and tyranny.

8. Wilhelm II (1859-1941), emperor of Germany and king of Prussia (1888-1918).

9. The Union, founded in 1888 and composed of members of parliaments of various nations, often held its conferences at the same time and place at which the world peace congresses were held.

10. The Open Door policy extends the opportunity of commercial intercourse with a country to all nations on equal terms.

The Nobel Peace Prize, 1901-2000

by Geir Lundestad*

Secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, 1990-2014

Introduction

This article is intended to serve as a basic survey of the history of the Nobel Peace Prize during its first 100 years. Since all the 107 Laureates selected from 1901 to 2000 are to be mentioned, the emphasis will be on facts and names. At the same time, however, I shall try to deal with two central questions about the Nobel Peace Prize. First, why does the Peace Prize have the prestige it actually has? Second, what explains the nature of the historical record the Norwegian Nobel Committee has established over these 100 years?

There are more than 300 peace prizes in the world. None is in any way as well known and as highly respected as the Nobel Peace Prize. The Oxford Dictionary of Twentieth Century World History, to cite just one example, states that the Nobel Peace Prize is “The world’s most prestigious prize awarded for the ‘preservation of peace’.” Personally, I think there are many reasons for this prestige: the long history of the Peace Prize; the fact that it belongs to a family of prizes, i.e. the Nobel family, where all the family members benefit from the relationship; the growing political independence of the Norwegian Nobel Committee; the monetary value of the prize, particularly in the early and in the most recent years of its history. In this context, however, I am going to concentrate on the historical record of the Nobel Peace Prize. In my opinion, the prize would never have enjoyed the kind of position it has today had it not been for the decent, even highly respectable, record the Norwegian Nobel Committee has established in its selections over these 100 years. One important element of this record has been the committee’s broad definition of peace, enough to take in virtually any relevant field of peace work.

On the second point, the selections of the Norwegian Nobel Committee reflected the insights primarily of the committee members and secondarily of its secretaries and advisors.

But, on a deeper level, they also generally reflected Norwegian definitions of the broader, Western values of an idealist, the often slightly left-of-center kind, but rarely so far left that the choices were not acceptable to Western liberal-internationalist opinion in general. The Norwegian government did not determine the choices of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, but these choices reflected the same mixture of idealism and realism that characterized Norwegian, and Scandinavian, foreign policy in general. As we shall see, some of the most controversial choices occurred when the Norwegian Nobel Committee suddenly awarded prizes to rather hard-line realist politicians.

Nobel’s will and the peace prize

When Alfred Nobel died on December 10, 1896, it was discovered that he had left a will, dated November 27, 1895, according to which most of his vast wealth was to be used for five prizes, including one for peace. The prize for peace was to be awarded to the person who “shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding of peace congresses.” The prize was to be awarded “by a committee of five persons to be elected by the Norwegian Storting.”

Nobel left no explanation as to why the prize for peace was to be awarded by a Norwegian committee while the other four prizes were to be handled by Swedish committees. On this point, therefore, we are dealing only with educated inferences. These are some of the most likely ones: Nobel, who lived most of his life abroad and who wrote his will at the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris, may have been influenced by the fact that, until 1905, Norway was in union with Sweden. Since the scientific prizes were to be awarded by the most competent, i.e. Swedish, committees at least the remaining prize for peace ought to be awarded by a Norwegian committee. Nobel may have been aware of the strong interest of the Norwegian Storting (Parliament) in the peaceful solution of international disputes in the 1890s. He might have in fact, considered Norway a more peace-oriented and more democratic country than Sweden. Finally, Nobel may have been influenced by his admiration for Norwegian fiction, particularly by the author Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, who was a well-known peace activist in the 1890s. Or it may have been a combination of all these factors.

While there was a great deal of controversy surrounding Nobel’s will in Sweden and that of the role of the designated prize-awarding institutions, certainly including the fact that the rebellious Norwegians were to award the Peace Prize, the Norwegian Storting quickly accepted its role as awarder of the Nobel Peace Prize. On April 26, 1897, a month after it had received formal notification from the executors of the will, the Storting voted to accept the responsibility, more than a year before the designated Swedish bodies took similar action. It was to take three years of various legal actions before the first Nobel Prizes could actually be awarded.

1901-1913: The peace prize to the organized peace movement

Although there was nothing in the statutes that prevented the Storting from naming international members, the members of the Nobel Committee of the Storting (as the committee was called until 1977) have all been Norwegians from the very beginning. They were selected by the Storting to reflect the strengths of the various parties, but the members elected their own chairman. From December 1901 and until his death in 1922, Jørgen Løvland was the chairman of the Nobel Committee. He was one of the leaders of the Venstre (Left) party and served briefly as Foreign Minister (1905-1907), and then as Prime Minister (1907-1908). A majority of the five committee members in this period consistently represented that party.

Initially, Venstre represented a broad democratic-nationalist coalition, emphasizing universal suffrage, first for men, later for women, and independence from Sweden. The party strongly wanted to isolate Norway from Great Power politics; not only did it want Norway’s full independence, but also some form of guaranteed permanent neutrality, based on the Swiss model. Yet at the same time, the party had a definite interest in international peace work in the form of mediation, arbitration and the peaceful solution of disputes. Small countries, certainly including Norway, were to show the world the way from Great Power politics to a world based on law and norms.

Norwegian parliamentarians, particularly from Venstre, took a strong interest in the Inter-Parliamentary Union formed in 1889. After Switzerland, Norway was the first country to pledge an annual contribution, first for its general operations (1895), and then for its office in Bern (1897). Norway was to have hosted the Union’s conference in 1893, but because of the tense situation vis-à-vis Sweden the conference in Oslo was held only in 1899. These same liberal politicians were also highly sympathetic to the peace groups and societies that sprang up in many countries in the last decades of the 1800s, groups which starting in 1889 were internationally organized in the more or less annual Universal Peace Congress. The Permanent International Peace Bureau, founded in 1891 in Bern, became the international headquarters of this popular movement. (The movement long struggled with difficult finances, despite small fixed annual grants from Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden and Norway.) A third element in the peace work of this period was the more official movement, culminating in the Hague Conferences of 1899 and 1907, called by Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, to the enormous surprise of the governments of most other major powers. (The tsar was never seriously considered for the Peace Prize.)

Those few members of the Nobel Committee who did not represent Venstre tended to be jurists who took a special interest in building peace through international law, a desire shared by Venstre. Thus, former conservative Prime Minister and law professor Francis Hagerup was a committee member from 1907 to 1920. He was also chairman of the Norwegian delegation to the second Hague Conference in 1907.

With this composition of the Nobel Committee in mind, the list of the Nobel Laureates for the years 1901 to 1914 comes as no big surprise. Of the 19 prizes awarded during this period, only two went to persons who did not represent the Inter-Parliamentary Union, popular peace groups or the international legal tradition. The first two elements may also be said to have reflected the point in Nobel’s will about the prize being awarded for “the holding and promotion of peace congresses.”

The first prize in 1901 was awarded to Frédéric Passy (and Jean Henry Dunant). Passy was an obvious choice for the first prize since he had been one of the main founders of the Inter-Parliamentary Union and also the main organizer of the first Universal Peace Congress. He was himself the leader of the French peace movement. In his own person, he thus brought together the two branches of the international organized peace movement, the parliamentary one and the broader peace societies.

In 1902, the Peace Prize was awarded to Élie Ducommun, veteran peace advocate and the first honorary secretary of the International Peace Bureau, and to Charles Albert Gobat, first Secretary General of the Inter-Parliamentary Union and who later became Secretary General of the International Peace Bureau. (In 1906-1908 Gobat coordinated both groups, further underlining the close relationship between them.) In 1903 the prize went to William Randal Cremer, the “first father” of the Inter-Parliamentary Union. In 1889, Bertha von Suttner had published her anti-war novel Lay Down Your Arms. After that, she was drawn into the international peace movement. She undoubtedly exercised considerable influence on Alfred Nobel, whom she had known since 1876, when he later decided to include the Peace Prize as one of the five prizes mentioned in his will. In 1905, she was awarded the Peace Prize, the first woman to receive such a distinction. Her supporters strongly felt that the prize had come too late, since she had had such an influence on Nobel. In 1907, the prize was awarded to Ernesto Teodoro Moneta, a key leader of the Italian peace movement. In 1908, the prize was divided between Fredrik Bajer, the foremost peace advocate in Scandinavia, combining work in the Inter-Parliamentary Union with being the first president of the International Peace Bureau, and Klas Pontus Arnoldson, founder of the Swedish Peace and Arbitration League. In 1910, the Permanent International Peace Bureau itself received the prize. In 1911, Alfred Hermann Fried, founder of the German Peace Society, leading peace publisher/educator and a close collaborator, shared it with Tobias Michael Carel Asser. In 1913, Henri La Fontaine was the first socialist to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. He was head of the International Peace Bureau from 1907 until his death in 1943. He was also active in the Inter-Parliamentary Union.

International legal work for peace represented the third road to the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1904, the Institute of International Law, the first organization or institution to receive the Peace Prize, was honored for its efforts as an unofficial body to formulate the general principles of the science of international law. In 1907, Louis Renault, leading French international jurist and a member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, shared the Peace Prize with Ernesto Teodoro Moneta. In 1909, the prize was shared between Paul Henri Benjamin Balluet, Baron d’Estournelles de Constant de Rebecque, who combined diplomatic work for Franco-German and Franco-British understanding with a distinguished career in international arbitration, and Auguste Marie François Beernaert, former Belgian Prime Minister, representative to the two Hague conferences, and a leading figure in the Inter-Parliamentary Union. Like d’Estournelles and Renault, Beernaert was also a member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration. Thus, few if any of the Laureates summed up the different stands of the early peace movement in the way Beernaert did. The Laureate of 1911, Tobias Michael Carel Asser, was also a member of the Court of Arbitration as well as the initiator of the Conferences on International Private Law. When America’s Elihu Root received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1912, he had served both as U.S. Secretary of War and Secretary of State. But he was awarded the prize primarily for his strong interest in international arbitration and for his plan for a world court, which was finally established in 1920.

Jean Henry Dunant (1901) and Theodore Roosevelt (1906) are the two Laureates who clearly fall outside any of the categories mentioned so far. Dunant, who founded the International Red Cross in 1863, had been more or less forgotten until a campaign secured him several international prizes, including the first Nobel Peace Prize. The Norwegian Nobel Committee thus established a broad definition of peace, arguing that even humanitarian work embodied “the fraternity between nations” that Nobel had referred to in his will. Roosevelt was the twenty-sixth president of the United States and the first in a long series of statesmen to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. He received the prize for his successful mediation to end the Russo-Japanese war and for his interest in arbitration, having provided the Hague arbitration court with its very first case. Internationally, however, he was best known for a rather bellicose posture, which certainly included the use of force. It is known that both the secretary and the relevant adviser of the Nobel Committee at that time were highly critical of an award to Roosevelt. It is thus tempting to speculate that the American president was honored at least in part because Norway, as a new state on the international arena, “needed a large, friendly neighbor – even if he is far away,” as one Norwegian newspaper put it. Even if, or perhaps rather because, the prize to Roosevelt was controversial, it did in some ways constitute a breakthrough in international media interest in the Nobel Peace Prize.

1914-1918: The First World War and the Red Cross

The First World War signified the collapse of the peaceful world which so many of the peace activists honored by the Nobel Peace Prize had worked so hard to establish. During the war, the number of nominations for the prize diminished somewhat, although a substantial number was still put forward. During the difficult war years, the Nobel Committee in neutral Norway decided to award no prize, except the one in 1917 to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The ICRC had been established in 1863 as a Swiss committee; the preceding year, the Convention for the Amelioration of the Conditions of the Wounded in Armies in the Field (the Geneva Convention) had been signed. During the First World War, the ICRC undertook the tremendous task of trying to protect the rights of the many prisoners of war on all sides, including their right to establish contacts with their families.

1919-1939: The League of Nations and the work for peace

In the 1920s, Venstre’s domination of the Nobel Committee continued even after the death of Jørgen Løvland and despite the choice of Conservative law professor Fredrik Stang (1922-1941) as the new chairman of the committee and the inclusion of Labor party historian Halvdan Koht in 1919. Old-timers Hans Jakob Horst and Bernhard Hanssen served on the committee from 1901 to 1931 and from 1913 to 1939, respectively. They were joined by Johan Ludwig Mowinckel (1925-1936) who meanwhile served as both Norway’s Prime Minister and Foreign Minister during three separate periods. In the 1930s, the membership of the committee became more mixed, but the Venstre members now maintained the balance between more conservative and social democratic members. Still, during the period from 1919 to 1939, the growing political tension within the committee and the presence of certain stubborn individuals, resulted in as many as nine “irregular” years, when either no prize was awarded or it was awarded one year late, compared to only one such year in the period from 1901 to 1913.

After the First World War, Norway became a member of the League of Nations. This break with the past was smaller than it might seem. In the Storting, 20 members, largely Social Democrats, voted against membership. Even most of the 100 who voted in favor came to insist on the right to withdraw from the sanctions regime of the League in case of war. Norway basically still perceived itself as a neutral state. The old ideals of mediation, arbitration, and the establishment of international legal norms definitely survived, only slightly tempered by the experiences of the war and the membership in the League. Yet at the same time, some states and some statesmen were definitely regarded as better than others. Most Norwegian foreign policy leaders felt closest to Great Britain and the United States, despite significant fishery disputes with the former and the geographical distance and isolationism of the latter.

At least eight of the 21 Laureates in the period from 1919 to 1939 had a clear connection with the League of Nations. For the Nobel Committee the League came to represent the enhancement of the Inter-Parliamentary Union tradition from before 1914. In 1919, the Peace Prize was awarded to the President of the United States, Thomas Woodrow Wilson for his crucial role in establishing the League. Wilson had been nominated by many, including Venstre Prime Minister Gunnar Knudsen. In a certain sense the prize to Wilson was obvious; what still made it controversial, also among committee members, was that the League was part of the Versailles Treaty, which was regarded as diverging from the president’s own ideal of “peace without victory.” The prize in 1920 to Léon Victor Auguste Bourgeois, a prominent French politician and peace activist, showed the continuity between the pre-1914 peace movement and the League. Bourgeois had participated in both the Hague Conferences of 1899 and 1907; in 1918-1919 he pushed for what became the League to such an extent that he was frequently called its “spiritual father.”

Swedish Social Democratic leader Karl Hjalmar Branting had also done long service for peace, but was particularly honored in 1921 with the Peace Prize for his work in the League of Nations. His fellow Laureate, Norway’s Christian Lous Lange, the first secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, had been the secretary-general of the Inter-Parliamentary Union since 1909 and had done important work in keeping the Union alive even during the war. After the war he was active in the League until his death in 1938. In 1922, the Norwegian Nobel Committee honored another Norwegian, Fridtjof Nansen, for his humanitarian work in Russia, which was done outside the League, but even more importantly for his work on behalf of the League to repatriate a great number of prisoners of war. From 1921, he was the League’s High Commissioner for Refugees. The refugee problem proved rather intractable. The Nansen International Office for Refugees was authorized by the League in 1930 and was closed only in 1938. For its work, it received that year’s Nobel Peace Prize.

In 1934, British Labour leader Arthur Henderson received the Peace Prize for his work for the League, particularly its efforts in disarmament. No single individual was more closely identified with the League from its beginning to its end than Viscount Cecil of Chelwood who was honored with the prize in 1937. Only Koht’s threat of resignation from the committee prevented the Peace Prize from being awarded directly to the League of Nations. In 1924, the committee even discussed awarding the prize to the Inter-Parliamentary Union.

In the years 1919-1939, the Nobel Committee also continued to honor the less official workers for peace. Since the peace societies of the pre-1914 period had lost most of their importance, this category of Laureates was now considerably more mixed than it had been in the earlier period. The clearest connection to the past was found in the shared prize for 1927 to Ludwig Quidde and Ferdinand Buisson. Buisson had joined his first peace society as early as 1867 and he had also been active in the Inter-Parliamentary Union, while the younger Quidde had joined the German Peace Society in 1892. In 1927, they were honored for their contributions to Franco-German popular reconciliation. In 1930, Lars Olof Nathan Söderblom was the first church leader to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to involve the churches not only in work for ecumenical unity, but also for world peace. In 1931, Jane Addams was honored for her social reform work, but even more for establishing in 1919, and then leading the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). Sharing the prize with Jane Addams was Nicholas Murray Butler, president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, promoter of the Briand-Kellogg pact and leader of the more establishment-oriented part of the American peace movement. Sir Norman Angell, who received the Peace Prize for 1933, had written his famous book The Great Illusion as early as 1910. In the book he argued that war did not pay, not that it was impossible as it was frequently understood to have stated. In the inter-war years, he was a strong supporter of the League of Nations as well as an influential publicist/educator for peace in general.

The most clear-cut representative in this period of the legal tradition to limit or even end war was the former American Secretary of State, Frank Billings Kellogg. He was awarded the 1929 Peace Prize for the Kellogg-Briand pact, whose signatories agreed to settle all conflicts by peaceful means and renounced war as an instrument of national policy.

While Theodore Roosevelt and, to a lesser extent, Elihu Root, were the only prominent international politicians to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in the years before 1914, at least five prominent politicians in addition to Kellogg were to be so honored between 1919 and 1939. In 1926 alone, the Nobel Committee actually awarded the reserved prize for 1925 to Vice President Charles Gates Dawes of the United States and Foreign Secretary Sir Austen Chamberlain of Great Britain and the 1926 prize to Foreign Minister Aristide Briand of France and Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann of Germany. Dawes was responsible for the Dawes Plan for German reparations which was seen as having provided the economic underpinning of the Locarno Pact of 1925, under which Germany accepted its western borders as final. The four prizes reflected recognition of the changed international political climate, particularly between Germany and France, which Locarno helped bring about. It was probably also an effort by the committee to strengthen Norway’s relations with the four international powers that mattered most for its interests. In 1936, the prize was awarded to Argentine Foreign Minister Carlos Saavedra Lamas for his mediation of an end to the Chaco War between Paraguay and Bolivia. Lamas also played a significant role in the League of Nations.