Speed read: Writing as living

Herta Müller has lived through the kind of vicious absurdity that most can only imagine. A member of Romania’s German minority, which was protected when Romania allied itself with Hitler, but was then persecuted under Ceauşescu’s communist dictatorship, she will always be an outsider, someone whose past will never allow them to fit in. Born in a German-speaking village, she had no real contact with Romanian until she was a teenager. She found work as a translator of technical manuals in a tractor factory, but after she refused to collaborate with the secret police, the harassment started. She turned up for work one day to find herself barred from her office. So she worked on the stairs. Then the secret police started to spread rumours that she was a police informer. Ironically, because she had refused to become a spy, people now believed she was one. She was eventually dismissed and later her apartment was bugged, she could not find work, she was picked up, questioned and kicked around.

Confronted by all this harassment she felt increasingly confused and started to write as a way of proving to herself that she still existed. Müller says that she learnt to live by writing, that writing was the only place where she could live by the standards she dreamt of and the only place where she could express what she could never live. She finally left Romania to settle in Germany in 1987. Müller writes short stories, novels, poems and essays, but all her work deals with the experience of oppression, of exile, of conforming to family and state. It deals with the difficulties of being oneself.

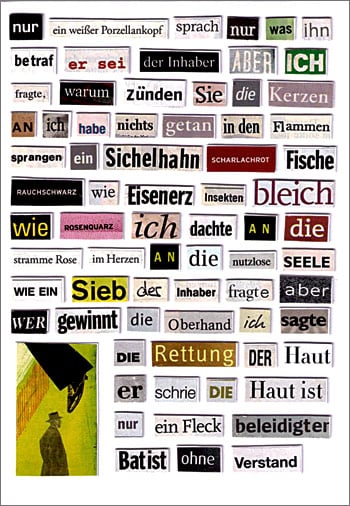

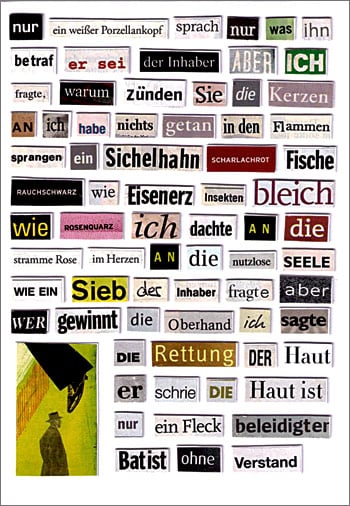

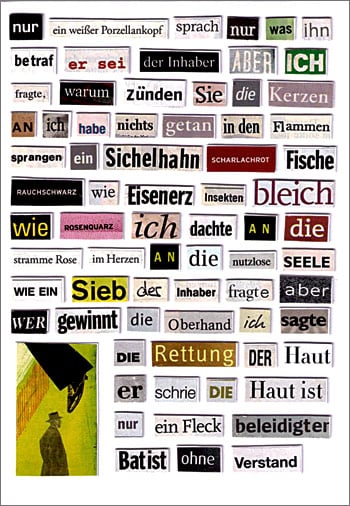

Her first book Nadirs (Niederungen, 1982, first published with full, uncensored text in 1984) describes life in a small village from a child’s point of view and, like all her work, is brutally frank about corruption and cruelty, whether shown by Romanians, or by the German minority. She expands details of ordinary life into fantastic images, words are used unconventionally and horror and absurdity are mixed with extreme poeticism. German is Müller’s mother tongue, but she uses German from another time and place, and in her essays Der König verneigt sich und tötet (2003) she discusses the importance of language as identity and exemplifies ways that language is used by the majority to brand immigrants and outsiders. Her strong attachment to Romanian clearly emerges in her collage-poems, in which she cuts out words or syllables from Romanian magazines and pastes them down to make poems. Once stuck down, you cannot change them, and Müller has said that this is what appeals to her about collage. A collage is like the past: you cannot wipe it away. It is part of who you are and who you will be.

Herta Müller – Prose

English

German

Auszug von Der Mensch ist ein großer Fasan auf der Welt

DIE TIEFE STELLE

Um das Kriegerdenkmal stehn Rosen. Sie sind ein Gestrüpp. So verwachsen, daß sie das Gras ersticken. Sie blühn weiß, klein zusammengerollt wie Papier. Sie rascheln. Es dämmert. Bald ist es Tag.

Windisch zählt jeden Morgen, wenn er ganz allein über die Straße in die Mühle fährt, den Tag. Vor dem Kriegerdenkmal zählt er die Jahre. Am ersten Pappelbaum dahinter, wo das Fahrrad immer in dieselbe tiefe Stelle fährt, zählt er die Tage. Und abends, wenn Windisch die Mühle zusperrt, zählt er die Jahre und Tage noch einmal.

Von weitem sieht er die kleinen weißen Rosen, das Kriegerdenkmal und den Pappelbaum. Und wenn Nebel ist, ist das Weiße der Rosen und das Weiße des Steins beim Fahren dicht vor ihm. Windisch fährt hindurch. Windisch hat ein feuchtes Gesicht und fährt, bis er dort ist. Zweimal hat das Rosengestrüpp kahle Dornen gehabt und das Unkraut darunter war rostig. Zweimal war die Pappel so kahl, daß ihr Holz fast zerbrochen wär. Zweimal war Schnee auf den Wegen.

Windisch zählt zwei Jahre vor dem Kriegerdenkmal und zweihunderteinundzwanzig Tage in der tiefen Stelle vor der Pappel.

Jeden Tag, wenn Windisch von der tiefen Stelle gerüttelt wird, denkt er: »Das Ende ist da.« Seit Windisch auswandern will, sieht er überall im Dorf das Ende. Und die stehende Zeit, für die, die bleiben wollen. Und daß der Nachtwächter dableibt, sieht Windisch, über das Ende hinaus.

Und nachdem Windisch zweihunderteinundzwanzig Tage gezählt und die tiefe Stelle ihn gerüttelt hat, steigt er zum ersten Mal ab. Er lehnt das Fahrrad an den Pappelbaum. Seine Schritte sind laut. Aus dem Kirchgarten flattern wilde Tauben. Sie sind grau wie das Licht. Nur der Lärm macht sie anders.

Windisch schlägt das Kreuz. Die Türklinke ist naß. Sie klebt an Windischs Hand. Die Kirchentür ist zugesperrt. Der heilige Antonius steht hinter der Wand. Er trägt eine weiße Lilie und ein braunes Buch. Er ist eingeschlossen.

Windisch friert. Er schaut die Straße runter. Wo sie aufhört, schlagen die Gräser ins Dorf. Am Ende dort geht ein Mann. Der Mann ist ein schwarzer Faden, der in die Pflanzen geht. Das schlagende Gras hebt ihn über die Erde.

DER KÖNIG SCHLÄFT

Vor dem Krieg hatte die Musikkapelle des Dorfes in dunkelroten Uniformen am Bahnhof gestanden. Der Bahnhofsgiebel war vollgehängt mit Girlanden aus Feuerlilien, aus Sommerastern und Akazienlaub. Die Leute hatten ihre Sonntagskleider an. Die Kinder trugen weiße Kniestrümpfe. Sie hielten schwere Blumensträuße vor den Gesichtern.

Als der Zug in den Bahnhof eingefahren war, spielte die Musikkapelle einen Marsch. Die Leute klatschten. Die Kinder warfen ihre Blumen in die Luft.

Der Zug war langsam gefahren. Ein junger Mann streckte seinen langen Arm zum Fenster heraus. Er spreizte die Finger und rief: »Ruhe. Seine Majestät, der König, schläft.«

Als der Zug aus dem Bahnhof hinausgefahren war, kam eine Schar weißer Ziegen von der Weide. Die Ziegen gingen den Schienen entlang und fraßen die Blumensträuße.

Die Musikanten waren nach Hause gegangen mit ihrem abgebrochenen Marsch. Die Männer und Frauen waren nach Hause gegangen mit ihrem abgebrochenen Winken. Die Kinder waren nach Hause gegangen mit leeren Händen.

Ein Mädchen, das dem König, nachdem der Marsch zu Ende war, nachdem das Klatschen zu Ende war, ein Gedicht hätte sagen sollen, saß, bis die Ziegen alle Blumensträuße gefressen hatten, allein im Wartesaal und weinte.

DIE BRENNENDE KUGEL

Die gefleckten Schweine des Nachbarn liegen in den wilden Möhren und schlafen. Die schwarzen Weiber kommen aus der Kirche. Die Sonne glänzt. Sie hebt sie über den Gehsteig in ihren kleinen schwarzen Schuhn. Sie haben mürbe Hände von den Rosenkränzen. Ihr Blick ist noch verklärt vom Beten.

Über das Dach des Kürschners schlägt die Kirchenglocke mitten in den Tag. Die Sonne ist die große Uhr über dem Mittagläuten. Das Hochamt ist zu Ende. Der Himmel ist heiß.

Hinter den kleinen, alten Weibern ist der Gehsteig leer. Windisch schaut den Häusern entlang. Er sieht das Ende der Straße. »Amalie müßte kommen«, denkt er. Im Gras stehen Gänse. Sie sind weiß wie Amalies weiße Sandalen.

Die Träne liegt im Schrank. »Amalie hat sie nicht gefüllt«, denkt Windisch. »Immer, wenn es regnet, ist Amalie nicht zu Haus. Immer ist sie in der Stadt.«

Der Gehsteig bewegt sich im Licht. Die Gänse segeln. Sie haben weiße Tücher in den Flügeln. Amalies schneeweiße Sandalen gehen nicht durchs Dorf.

Die Schranktür knarrt. Die Flasche gluckst. Windisch hält eine nasse brennende Kugel auf der Zunge. Die Kugel rollt ihm durch den Hals. In Windischs Schläfen flackert ein Feuer. Die Kugel löst sich auf. Sie zieht heiße Fäden durch Windischs Stirn. Sie drückt verzackte Rinnen wie Scheitel durch sein Haar.

Die Mütze des Milizmanns dreht sich um den Spiegelrand. Seine Schulterklappen blinken. Die Knöpfe seines blauen Rocks wachsen in die Spiegelmitte. Über dem Rock des Milizmanns steht Windischs Gesicht.

Windischs Gesicht steht einmal groß und überlegen überm Rock. Zweimal lehnt Windischs Gesicht klein und verzagt über den Schulterklappen. Der Milizmann lacht zwischen Windischs Wangen in Windischs großem, überlegenem Gesicht. Er sagt mit nassen Lippen: »Mit deinem Mehl kommst du nicht weit.«

Windisch hebt die Fäuste. Der Rock des Milizmanns zersplittert. Windischs großes, überlegenes Gesicht hat einen Blutfleck. Windisch schlägt die beiden kleinen, verzagten Gesichter über den Schulterklappen tot.

Windischs Frau kehrt stumm den zerbrochenen Spiegel zusammen.

Excerpts from: Herta Müller, Der Mensch ist ein großer Fasan auf der Welt

Copyright © Carl Hanser Verlag München 2009

Published by permission of Carl Hanser Verlag

Excerpt selected by the Nobel Library of the Swedish Academy.

Herta Müller – Photo gallery

Herta Müller receiving her Nobel Prize from His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Herta Müller after receiving her Nobel Prize at the Stockholm Concert Hall, 10 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Close-up from the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony (from left to right): Jack W. Szostak, Herta Müller and Elinor Ostrom.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

The 2009 Nobel Laureates stand for the Swedish national anthem (from left to right): Charles K. Kao, Willard S. Boyle, George E. Smith, Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz, Ada E. Yonath, Elizabeth H. Blackburn, Carol W. Greider, Jack W. Szostak, Herta Müller, Elinor Ostrom and Oliver E. Williamson.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Nobel Laureate Herta Müller in conversation with Dr Johann Deisenhofer, 1988 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, at the Nobel Banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Escorted by a student, Herta Müller walks towards the podium to deliver her banquet speech at the Nobel Banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 2009.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Herta Müller delivers her banquet speech at the Nobel Banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 2009. To her left stands Ruth Jacoby, who translated the speech into English.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

From left to right: Prince Carl Philip, His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, Her Majesty Queen Silvia, Nobel Laureate Herta Müller and her husband, Dr Harry Merkle, Crown Princess Victoria, and Princess Madeleine at the Nobel Banquet.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

The 2009 Nobel Laureates assembled for a group photo during their visit to the Nobel Foundation, 12 December 2009. Back row, left to right: Nobel Laureates in Chemistry Ada E. Yonath and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Jack W. Szostak and Carol W. Greider, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry Thomas A. Steitz, Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine Elizabeth H. Blackburn, and Nobel Laureate in Physics George E. Smith. Front row, left to right: Nobel Laureate in Physics Willard S. Boyle, Laureate in Economic Sciences Elinor Ostrom, Nobel Laureate in Literature Herta Müller and Laureate in Economic Sciences, Oliver E. Williamson.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Herta Müller signing books at the Nobel Museum in Stockholm,

11 December 2009.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2009

Herta Müller delivering her Nobel Lecture at the Swedish Academy, 7 December 2009.

© The Swedish Academy 2009

Photo: Helena Paulin-Strömberg

Herta Müller after delivering her Nobel Lecture at the Swedish Academy, 7 December 2009. On her right, Professor Peter Englund, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy.

Copyright © The Swedish Academy 2009

Photo: Helena Paulin-Strömberg

Herta Müller during the interview with Nobelprize.org in Stockholm, 6 December 2009.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2009

Herta Müller during the interview with Nobelprize.org in Stockholm, 6 December 2009. The interviewer is Marika Griehsel, freelance journalist.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2009

Herta Müller signing books.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2009

Herta Müller reads an extract from her book "Der Mensch ist ein großer Fasan auf der Welt" for Nobelprize.org.

Copyright © Nobel Media AB 2009

Herta Müller signing her new book Atemschaukel in a German book store.

Photo: Public domain, Wikipedia Commons

Herta Müller visits the Nobel Museum exhibition Literary Rebellion on 6 October 2017. © Nobel Museum. Photo: Clément Morin

Herta Müller at the Gothenburg Book Fair in 2008.

Photo: Håkan Lindgren

Kindly provided by Håkan Lindgren

Herta Müller in Gamla stan, the Old Town, in Stockholm, Sweden.

Photo: Ulla Montan

Photo: Frida Westholm

Photo: Frida Westholm

Photo: Frida Westholm

Photo: Frida Westholm

Photo: Orasisfoto

Photo: Orasisfoto

Photo: Orasisfoto

Photo: Orasisfoto

Photo: Orasisfoto

Photo: Annalisa B. Andersson

Photo: Niclas Enberg

Photo: Niclas Enberg

Photo: Niclas Enberg

Photo: Niclas Enberg

Herta Müller – Prose

2009 Nobel Laureate in Literature Herta Müller reads ‘Die Tiefe Stelle’ from her book “Der Mensch ist ein großer Fasan auf der Welt”. The video was recorded in Stockholm in December 2009.

Read the excerpts from The Passport (Der Mensch ist ein großer Fasan auf der Welt)

English

German

Excerpts from The Passport

THE POT HOLE

Around the war memorial are roses. They form a thicket. So overgrown that they suffocate the grass. Their blooms are white, rolled tight like paper. They rustle. Dawn is breaking. Soon it will be day.

Every morning, as he cycles alone along the road to the mill, Windisch counts the day. In front of the war memorial he counts the years. By the first poplar tree beyond it, where he always hits the same pot hole, he counts the days. And in the evening, when Windisch locks up the mill, he counts the years and the days once again.

He can see the small white roses, the war memorial and the poplar tree from far away. And when it is foggy, the white of the roses and the white of the stone is close in front of him as he rides. Windisch rides on. Windisch’s face is damp, and he rides till he’s there. Twice the thorns on the rose thicket were bare and the weeds underneath were rusty. Twice the poplar was so bare that its wood almost split. Twice there was snow on the paths.

Windisch counts two years by the war memorial and two hundred and twenty-one days in the pot hole by the poplar.

Every day when Windisch is jolted by the pot hole, he thinks, “The end is here.” Since Windisch made the decision to emigrate, he sees the end everywhere in the village. And time standing still for those who want to stay. And Windisch sees that the night watchman will stay beyond the end.

And after Windisch has counted two hundred and twenty-one days and the pot hole has jolted him, he gets off for the first time. He leans the bicycle against the poplar tree. His steps are loud. Wild pigeons flutter out of the churchyard. They are as grey as the light. Only the noise makes them different.

Windisch crosses himself. The door latch is wet. It sticks to Windisch’s hand. The church door is locked. Saint Anthony is on the other side of the wall. He is carrying a white lily and a brown book. He is locked in.

Windisch shivers. He looks down the street. Where it ends, the grass beats into the village. A man is walking at the end of the street. The man is a black thread walking into the field. The waves of grass lift him above the ground.

THE KING IS SLEEPING

Before the war the village band had stood at the station in their dark red uniforms. The station gable was hung with garlands of tiger-lilies, China asters and acacia foliage. People were wearing their Sunday clothes. The children wore white knee socks. They held heavy bouquets of flowers in front of their faces.

When the train steamed into the station, the band played a march. People clapped. The children threw their flowers in the air.

The train moved slowly. A young man stretched his long arm out of the window. He spread his fingers and called: “Silence. His Majesty the King is sleeping.”

When the train had left the station, a herd of white goats came from the meadow. They went along the tracks and ate the bouquets of flowers.

The musicians had gone home with their interrupted march. The men and women had gone home with their interrupted waving. The children had gone home with empty hands.

A little girl who was to have recited a poem for the King when the march had finished, when the clapping had finished, sat in the waiting room and cried, until the goats had eaten all the bunches of flowers.

THE BURNING GLOBE

The neighbour’s spotted pigs are lying in the wild carrots, sleeping. The black women come out of the church. The sun-shine is bright. It lifts them over the pavement in their small black shoes. Their hands are worn from the rosaries. Their gaze is still radiant from praying.

Above the skinner’s roof the church bell strikes the middle of the day. The sun is a great clock above the midday tolling. Mass is over. The sky is hot.

Behind the small, old women the pavement is empty. Windisch looks along the houses. He sees the end of the street. “Amalie should be coming,” he thinks. There are geese in the grass. They are white like Amalie’s white sandals.

The tear lies in the cupboard. “Amalie didn’t fill it,” thinks Windisch. “Amalie’s never at home when it rains. She’s always in town.”

The pavement moves in the light. The geese sail along. They have white sails in their wings. Amalie’s snow-white sandals don’t walk through the village.

The cupboard door creaks. The bottle gurgles. Windisch holds a wet burning globe on his tongue. The globe rolls down his throat. A fire flickers in Windisch’s temples. The globe dissolves. It draws hot threads through Windisch’s forehead. It pushes crooked furrows like partings through his hair.

The militiaman’s cap circles round the edge of the mirror. His epaulettes flash. The buttons of his blue jacket grow larger in the centre of the mirror. Windisch’s face appears above the militiaman’s jacket.

First Windisch’s face appears large and confident above the jacket. Then Windisch’s face is small and dejected above the epaulettes. The militiaman laughs between the cheeks of Windisch’s large, confident face. With wet lips he says: “You won’t get far with your flour.”

Windisch raises his fists. The militiaman’s jacket shatters. Windisch’s large, confident face has a spot of blood. Windisch strikes the two small, despondent faces above the epaulettes dead.

Windisch’s wife silently sweeps up the broken mirror.

Excerpts from: Herta Müller, The Passport, 2009, translated by Martin Chalmers, London, Serpent’s Tail

Original title: Der Mensch ist ein großer Fasan auf der Welt

Translation copyright © Serpent’s Tail, 1989

Published by permission of Serpent’s Tail

Excerpt selected by the Nobel Library of the Swedish Academy.

Herta Müller – Banquet speech

Herta Müller’s speech at the Nobel Banquet in the Stockholm City Hall, 10 December 2009.

English

German

Your Majesties

Your Royal Highnesses

Ladies and Gentlemen

Dear Friends

The trajectory that leads from a child tending cows in the valley to the Stockholm City Hall is a strange one. Here, too, (as is often the case), I am standing beside myself.

It was only against my mother’s will that I attended the preparatory high school in the city. She wanted me to become a seamstress in the village. She knew that if I moved to the city I would become corrupted. And I was. I started to read books. The village seemed more and more to me like a box in which a person was born, married and died. All the people in the village inhabited an older time, they were born old. I thought: sooner or later you have to leave the village if you want to grow young. In the village everyone cowered before the state, but among themselves and towards each other they were obsessively controlling, to the point of self-destruction. The same mix of cowardice and control could be found throughout the city as well. Private cowardice to the point of self-destruction, state control to the point of breaking the individual. That is perhaps the shortest way to describe daily life during the dictatorship.

Fortunately I made some friends in the city, a handful of young writers from the Aktionsgruppe Banat. Without them I wouldn’t have read or written any books at all. More importantly: these friends were absolutely essential. Had it not been for them I wouldn’t have been able to stand the repression. Today I am thinking of these friends, including the ones in the cemetery – the ones that the Romanian secret service has on its conscience.

I saw many people break down. I was on the verge of doing so myself, but shortly before that happened I was able to leave Romania. I’d already had a great deal of luck, all undeserved, since luck is not something that can be deserved. Happiness may perhaps be shared. But not luck, sadly. Now, standing here beside myself in Stockholm, I’m very lucky once again. Because this prize helps both those who lived through the kind of repression that aims to break human beings and those who, thank God, did not have to: the ones to remember what they experienced, and the others to bear these things in mind. Because to this very day there are dictatorships of every stripe. Some go on forever, always frightening us anew, such as Iran. Others, such as Russia and China, don cloaks of respectability; they liberalize their economies, but human rights remain firmly in the grip of Stalinism or Maoism. And then there are the half-democracies of Eastern Europe, which since 1989 have been putting on and taking off their respectable cloaks so often that they’re practically in tatters.

Literature can’t change all of that. But it can – and this is in hindsight – use language to invent a truth that shows what happens in us and around us when values become derailed.

Literature speaks with everyone individually – it is personal property that stays inside our heads. And nothing speaks to us as forcefully as a book, which expects nothing in return, other than that we think and feel.

I’d like to thank the Swedish Academy and the Nobel Foundation – many thanks.

Translated by Philip Boehm

Herta Müller – Prize presentation

Watch a video clip of the 2009 Nobel Laureate in Literature, Herta Müller, receiving her Nobel Prize medal and diploma during the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Concert Hall in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10 December 2009.

Herta Müller – Banquet speech

Herta Müller delivering her banquet speech.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2009

Photo: Orasisfoto

English

German

Herta Müller’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 2009

Eure Majestäten

Eure Königlichen Hoheiten

Meine Damen und Herren

Liebe Freunde

Der Bogen von einem Kind, das Kühe hütet im Tal bis hierher ins Rathaus von Stockholm ist bizarr. Ich stehe (wie so oft) auch hier neben mir selbst.

In die Stadt aufs Gymnasium kam ich nur gegen den Willen meiner Mutter. Sie wollte, daß ich im Dorf Schneiderin werde. Sie wußte, daß ich in der Stadt verdorben werde. Und ich wurde verdorben. Ich fing an, Bücher zu lesen. Das Dorf kam mir immer mehr vor wie eine Kiste, in der man geboren wird, heiratet, stirbt. Alle Dorfleute lebten in einer alten Zeit, wurden schon alt geboren. Man muß das Dorf irgendwann verlassen, wenn man jung werden will, dachte ich. Im Dorf waren alle vor dem Staat geduckt, aber untereinander und gegen sich selbst kontrollwütig bis zur Selbstzerstörung. Feigheit und Kontrolle – beides war später auch in der Stadt allgegenwärtig. Privat Feigheit bis zur Selbstzerstörung, staatlich Kontrolle bis zur Zerrüttung des Individuums. Es ist vielleicht die kürzeste Form, die Tage in der Diktatur zu beschreiben.

Zum Glück traf ich in der Stadt Freunde, eine Handvoll junge Dichter der „Aktionsgruppe Banal” Ohne sie hätte ich keine Bücher gelesen und keine geschrieben. Noch wichtiger ist: Diese Freunde waren lebensnotwendig. Ohne sie hätte ich die Repressalien nicht ausgehalten. Ich denke heute an diese Freunde. Auch an die, die auf dem Friedhof liegen, die der rumänische Geheimdienst auf dem Gewissen hat.

Ich habe viele Menschen zerbrechen sehen. Und ich war selbst am Zerbrechen. Kurz davor konnte ich Rumänien verlassen. Ich hatte schon damals viel Glück – unverdientes Glück, denn Glück kann man sich nicht verdienen. GLÜCKLICHSEIN ist vielleicht teilbar. GLÜCKHABEN leider nicht. Und indem ich hier in Stockholm neben mir stehe, habe ich wieder mal großes Glück. Denn dieser Preis hilft, die geplante Zerstörung von Menschen durch Repression im Gedächtnis derer zu behalten, die sie erlebt haben – und sie denen ins Gedächtnis zu rufen, die sie gottseidank nicht erleben mußten. Denn es gibt bis heute Diktaturen aller Couleur. Manche dauern schon ewig und erschrecken uns gerade wieder aufs Neue, wie der Iran. Andere, wie Rußland und China ziehen sich zivile Mäntelchen an, liberalisieren ihre Wirtschaft – die Menschenrechte sind jedoch noch längst nicht vom Stalinismus oder Maoismus losgelöst. Und es gibt die Halbdemokratien Osteuropas, die das zivile Mäntelchen seit 1989 ständig an – und ausziehen, so daß es schon fast zerrissen ist.

Literatur kann das alles nicht ändern. Aber sie kann – und sei es im Nachhinein – durch Sprache eine Wahrheit erfinden, die zeigt, was in und um uns hemm passiert, wenn die Werte entgleisen.

Literatur spricht mit jedem Menschen einzeln – sie ist Privateigentum, das im Kopf bleibt. Nichts sonst spricht so eindringlich mit uns selbst wie ein Buch. Und erwartet nichts dafür, außer daß wir denken und fühlen.

Ich danke der Schwedischen Akademie und der Nobelstiftung – vielen Dank.

Herta Müller – Nobelvorlesung

English

English [pdf]

Swedish

Swedish [pdf]

French

French [pdf]

German

German [pdf]

Spanish

Spanish [pdf]

7. Dezember 2009

Jedes Wort weiß etwas vom Teufelskreis

HAST DU EIN TASCHENTUCH, fragte die Mutter jeden Morgen am Haustor, bevor ich auf die Straße ging. Ich hatte keines. Und weil ich keines hatte, ging ich noch mal ins Zimmer zurück und nahm mir ein Taschentuch. Ich hatte jeden Morgen keines, weil ich jeden Morgen auf die Frage wartete. Das Taschentuch war der Beweis, daß die Mutter mich am Morgen behütet. In den späteren Stunden und Dingen des Tages war ich auf mich selbst gestellt. Die Frage HAST DU EIN TASCHENTUCH war eine indirekte Zärtlichkeit. Eine direkte wäre peinlich gewesen, so etwas gab es bei den Bauern nicht. Die Liebe hat sich als Frage verkleidet. Nur so ließ sie sich trocken sagen, im Befehlston wie die Handgriffe der Arbeit. Daß die Stimme schroff war, unterstrich sogar die Zärtlichkeit. Jeden Morgen war ich ein Mal ohne Taschentuch am Tor und ein zweites Mal mit einem Taschentuch. Erst dann ging ich auf die Straße, als wäre mit dem Taschentuch auch die Mutter dabei.

Und zwanzig Jahre später war ich längst für mich allein in der Stadt, Übersetzerin in einer Maschinenbau-Fabrik. Fünf Uhr morgens stand ich auf, halb sieben Uhr fing die Arbeit an. Morgens schallte aus dem Lautsprecher die Hymne über den Fabrikhof. In der Mittagspause die Arbeiterchöre. Aber die Arbeiter, die beim Essen saßen, hatten leere Augen wie Weißblech, ölverschmierte Hände, ihr Essen war in Zeitungspapier gewickelt. Bevor sie ihr Stückchen Speck aßen, kratzten sie mit dem Messer die Druckerschwärze von ihrem Speck. Zwei Jahre vergingen im Trott der Alltäglichkeit, ein Tag glich dem anderen.

Im dritten Jahr war es mit der Gleichheit der Tage vorbei. Innerhalb einer Woche kam dreimal frühmorgens ein riesengroßer dickknochiger Mann mit funkelnd blauen Augen, ein Koloß vom Geheimdienst in mein Büro.

Das erste Mal beschimpfte er mich im Stehen und ging.

Das zweite Mal zog er seine Windjacke aus, hängte sie an den Schrankschlüssel und setzte sich. Ich hatte an diesem Morgen von zu Hause Tulpen mitgebracht und arrangierte sie in der Vase. Er schaute mir zu und lobte mich für meine ungewöhnliche Menschenkenntnis. Seine Stimme war glitschig. Es war mir nicht geheuer. Ich bestritt das Lob und versicherte, daß ich mich in Tulpen auskenne, aber nicht in Menschen. Da sagte er maliziös, daß er mich besser kenne, als ich die Tulpen. Dann hängte er sich die Windjacke auf den Arm und ging.

Das dritte Mal setzte er sich und ich blieb stehen, denn er hatte seine Aktentasche auf meinen Stuhl gelegt. Ich wagte es nicht, sie auf den Boden zu stellen. Er beschimpfte mich als stockdumm, arbeitsfaul, als Flittchen, so verdorben wie eine streunende Hündin. Die Tulpen schob er knapp an den Tischrand, auf die Tischmitte legte er ein leeres Blatt Papier und einen Stift. Er brüllte: Schreiben. Ich schrieb im Stehen, was er mir diktierte – meinen Namen mit Geburtsdatum und Adresse. Dann aber, daß ich unabhängig von Nähe oder Verwandtschaft niemandem sage, daß ich … jetzt kam das schreckliche Wort: colaborez, daß ich kollaboriere. Dieses Wort schrieb ich nicht mehr. Ich legte den Stift hin und ging zum Fenster, sah auf die staubige Straße hinaus. Sie war nicht asphaltiert, Schlaglöcher und bucklige Häuser. Diese ruinierte Gasse hieß auch noch Strada Gloriei, Straße des Ruhms. Auf der Straße des Ruhms saß eine Katze im nackten Maulbeerbaum. Es war die Fabrikskatze mit dem zerrissenen Ohr. Über ihr eine frühe Sonne wie eine gelbe Trommel. Ich sagte: N-am caracterul, ich hab nicht diesen Charakter. Ich sagte es der Straße draußen. Das Wort CHARAKTER machte den Geheimdienstmann hysterisch. Er zerriß das Blatt und warf die Schnipsel auf den Boden. Wahrscheinlich fiel ihm ein, daß er seinem Chef den Anwerbungsversuch präsentieren muß, denn er bückte sich, sammelte alle Fetzen in die Hand und warf sie in seine Aktentasche. Dann seufzte er tief und warf in seiner Niederlage die Blumenvase mit den Tulpen an die Wand. Sie zerschellte und es knirschte, als wären Zähne in der Luft. Mit der Aktentasche unterm Arm sagte er leis: Dir wird es noch leidtun, wir ersäufen dich im Fluß. Ich sagte wie zu mir selbst: Wenn ich das unterschreibe, kann ich nicht mehr mit mir leben, dann muß ich es selber tun. Besser Sie machen es. Da stand hier die Bürotür schon offen und er war weg. Und draußen auf der Strada Gloriei war die Fabrikskatze vom Baum aufs Hausdach gesprungen. Ein Ast federte wie ein Trampolin.

Am nächsten Tag fing das Gezerre an. Ich sollte aus der Fabrik verschwinden. Jeden Morgen halb sieben mußte ich mich beim Direktor präsentieren. Mit ihm saßen jeden Morgen der Chef der Gewerkschaft und der Parteisekretär. Wie seinerzeit die Mutter fragte: Hast du ein Taschentuch, fragte jetzt der Direktor jeden Morgen: Hast du eine andere Arbeit gefunden. Ich antwortete jedes Mal dasselbe: Ich suche keine, mir gefällt es hier in der Fabrik, ich möchte bis zur Rente bleiben.

Eines Morgens kam ich zur Arbeit und meine dicken Wörterbücher lagen im Gang auf dem Boden neben der Bürotür. Ich öffnete, an meinem Schreibtisch saß ein Ingenieur. Er sagte: Hier klopft man an, wenn man hereinkommt. Hier sitze ich, du hast hier nichts zu suchen. Nach Hause gehen konnte ich nicht, sonst hätte man einen Vorwand gehabt, mich wegen unentschuldigtem Fehlen entlassen können. Ich hatte kein Büro, mußte jetzt erst recht jeden Tag normal zur Arbeit kommen, durfte auf keinen Fall fehlen.

Meine Freundin, der ich jeden Tag auf dem Heimweg durch die elendige Strada Gloriei alles erzählte, machte mir die erste Zeit eine Ecke an ihrem Schreibtisch frei. Doch eines Morgens stand sie vor der Bürotür und sagte: Ich darf dich nicht hereinlassen. Alle sagen, du bist ein Spitzel. Die Schikanen wurden nach unten gereicht, das Gerücht unter den Kollegen in Umlauf gesetzt. Das war das Schlimmste. Gegen Angriffe kann man sich wehren, gegen Verleumdung ist man machtlos. Ich rechnete jeden Tag mit allem, auch mit dem Tod. Aber mit dieser Perfidie wurde ich nicht fertig. Keine Rechnung machte sie erträglich. Verleumdung stopft einen aus mit Dreck, man erstickt, weil man sich nicht wehren kann. In der Meinung der Kollegen war ich genau das, was ich verweigert hatte. Wenn ich sie bespitzelt hätte, hätten sie mir ahnungslos vertraut. Im Grunde bestraften sie mich, weil ich sie schonte.

Da ich jetzt erst recht nicht fehlen durfte, aber kein Büro hatte, und meine Freundin mich in ihres nicht mehr lassen durfte, stand ich unschlüssig im Treppenhaus. Ich ging die Treppen ein paarmal auf und ab – plötzlich war ich wieder das Kind meiner Mutter, denn ICH HATTE EIN TASCHENTUCH. Ich legte es zwischen der ersten und zweiten Etage auf eine Treppenstufe, strich es glatt, daß es ordentlich liegt, und setzte mich drauf. Meine dicken Wörterbücher legte ich aufs Knie und übersetzte die Beschreibungen von hydraulischen Maschinen. Ich war ein Treppenwitz und mein Büro ein Taschentuch. Meine Freundin setzte sich in den Mittagspausen auf die Treppe zu mir. Wir aßen zusammen wie früher in ihrem und noch früher in meinem Büro. Aus dem Hoflautsprecher sangen wie immer die Arbeiterchöre vom Glück des Volkes. Sie aß und weinte um mich. Ich nicht. Ich mußte hart bleiben. Noch lange. Ein paar ewige Wochen, bis ich entlassen wurde.

In der Zeit, als ich ein Treppenwitz war, habe ich im Lexikon nachgeblättert, was es mit dem Wort TREPPE auf sich hat: Die erste Stufe der Treppe heißt ANTRITT, die letzte Stufe AUSTRITT. Die waagerechten Stufen zum Drauftreten sind seitlich in die TREPPENWANGEN eingepasst. Und die Freiräume zwischen den einzelnen Stufen heißen sogar TREPPENAUGEN. Von den Bauteilen der hydraulischen, ölverschmierten Maschinen kannte ich die schönen Wörter: SCHWALBENSCHWANZ, SCHWANENHALS, der Halt der Schrauben hieß SCHRAUBENMUTTER. Und genauso verblüfften mich die poetischen Namen der Treppenteile, die Schönheit der technischen Sprache. TREPPENWANGEN, TREPPENAUGEN – also hat die Treppe ein Gesicht. Ob aus Holz oder Stein, Beton oder Eisen – wieso bauen die Menschen selbst in die sperrigsten Dinge der Welt ihr eigenes Antlitz hinein, geben totem Material die Namen vom eigenen Fleisch, personifizieren es zu Körperteilen. Wird den Spezialisten der Technik die schroffe Arbeit erst erträglich durch versteckte Zärtlichkeit. Läuft jede Arbeit, in jedem Beruf, nach demselben Prinzip wie die Frage meiner Mutter nach dem Taschentuch.

Es gab zu Hause in meiner Kindheit eine Taschentuchschublade. Darin lagen in zwei Reihen hintereinander je drei Stapel:

Links die Männertaschentücher für den Vater und Großvater.

Rechts die Frauentaschentücher für die Mutter und Großmutter.

In der Mitte die Kindertaschentücher für mich.

Die Schublade war unser Familienbild im Taschentuchformat. Die Männertaschentücher waren die größten, hatten dunkle Randstreifen in Braun, Grau oder Bordeaux. Die Frauentaschentücher waren kleiner, ihre Ränder hellblau, rot oder grün. Die Kindertaschentücher waren die kleinsten, ohne Rand, aber im weißen Viereck mit Blumen oder Tieren bemalt. Von allen drei Taschentuchsorten gab es Werktagstaschentücher, in der vorderen Reihe, und Sonntagstaschentücher, in der hinteren Reihe. Sonntags mußte das Taschentuch, auch wenn man es nicht sah, zur Farbe der Kleider passen.

Kein anderer Gegenstand im Haus, nicht einmal wir selber, waren uns jemals so wichtig wie das Taschentuch. Es war universell nutzbar für: Schnupfen, Nasebluten, verletzte Hand, Ellbogen oder Knie, Weinen oder Draufbeißen und das Weinen unterdrücken. Ein nasses, kaltes Taschentuch auf der Stirn war gegen Kopfweh. Mit vier Knoten an den Ecken war es eine Kopfbedeckung gegen Sonnenbrand oder Regen. Wenn man sich etwas merken wollte, machte man sich einen Knoten als Gedächtnisstütze ins Taschentuch. Zum Tragen schwerer Taschen wickelte man es um die Hand. Flatternd wurde es ein Abschiedswinken, wenn der Zug aus dem Bahnhof fuhr. Und weil der Zug auf Rumänisch TREN und die Träne im Banater Dialekt TRÄN heißt, glich das Quietschen der Züge auf den Schienen in meinem Kopf immer dem Weinen. Wenn im Dorf einer zu Hause starb, band man ihm sofort ums Kinn herum ein Taschentuch, damit der Mund geschlossen bleibt, wenn die Leichenstarre fertig ist. Wenn am Wegrand in der Stadt einer umfiel, fand sich immer ein Passant, der dem Toten das Gesicht zudeckte mit seinem Taschentuch – so war das Taschentuch seine erste Totenruhe.

An heißen Sommertagen schickten die Eltern ihre Kinder spätabends auf den Friedhof Blumen gießen. Zu zweit oder zu dritt, man blieb von einem Grab zum anderen beisammen, goss schnell. Dann setzten wir uns eng aneinander auf die Treppen der Kapelle und schauten, wie aus manchen Gräbern weiße Dunstfetzen stiegen. Sie flogen ein bißchen in der schwarzen Luft und verschwanden. Für uns waren es die Seelen der Toten: Tiergestalten, Brillen, Fläschchen und Tassen, Handschuhe und Strümpfe. Und dazwischen hier und da ein weißes Taschentuch mit dem schwarzen Rand der Nacht.

Später, als ich mit Oskar Pastior Gespräche führte, um über seine Deportation ins sowjetische Arbeitslager zu schreiben, erzählte er, daß er von einer alten russischen Mutter ein Taschentuch aus weißem Batist bekommen hat. Vielleicht habt ihr Glück du und mein Sohn, und dürft bald nach Hause, sagte die Russin. Ihr Sohn war so alt wie Oskar Pastior und von zu Hause so weit weg wie er, in der anderen Richtung, sagte sie, in einem Strafbataillon. Als halbverhungerter Bettler hat Oskar Pastior an ihre Tür geklopft, wollte einen Brocken Kohle für ein bißchen Essen tauschen. Sie ließ ihn ins Haus, gab ihm heiße Suppe. Und als seine Nase in den Teller tropfte – das weiße Taschentuch aus Batist, das noch nie jemand benutzt hatte. Mit einem Ajour-Rand, akkurat genähten Stäbchen und Rosetten aus Seidenzwirn war das Taschentuch eine Schönheit, die den Bettler umarmte und verletzte. Eine Mixtur, einerseits Trost aus Batist, andererseits ein Meßband mit Seidenstäbchen, den weißen Strichlein auf der Skala seiner Verwahrlosung. Oskar Pastior selbst war eine Mixtur für diese Frau: weltfremder Bettler im Haus und verlorenes Kind in der Welt. In diesen zwei Personen war er beglückt und überfordert von der Geste einer Frau, die für ihn auch zwei Personen war: fremde Russin und besorgte Mutter mit der Frage: HAST DU EIN TASCHENTUCH.

Ich habe, seitdem ich diese Geschichte kenne, auch eine Frage: Ist HAST DU EIN TASCHENTUCH überall gültig und im Schneeglanz zwischen Frieren und Tauen über die halbe Welt gespannt. Geht sie zwischen Bergen und Steppen über alle Grenzen, bis hinein in ein riesiges mit Straf- und Arbeitslagern übersätes Imperium. Ist die Frage HAST DU EIN TASCHENTUCH nicht einmal mit Hammer und Sichel, nicht einmal im Stalinismus der Umerziehung durch die vielen Lager totzukriegen?

Obwohl ich seit Jahrzehnten rumänisch spreche, fiel mir im Gespräch mit Oskar Pastior zum ersten mal auf: Taschentuch heißt auf Rumänisch BATISTA. Wieder mal das sinnliche Rumänisch, das seine Wörter zwingend einfach ins Herz der Dinge jagt. Das Material macht keinen Umweg, bezeichnet sich als fertiges Taschentuch, als BATISTA. Als wäre jedes Taschentuch jederzeit und überall aus Batist.

Oskar Pastior hat das Taschentuch als Reliquie von einer Doppelmutter mit einem Doppelsohn im Koffer aufbewahrt. Und dann nach fünf Lagerjahren mit nach Hause genommen. Warum – sein weißes Taschentuch aus Batist war Hoffnung und Angst. Wenn man Hoffnung und Angst aus der Hand gibt, stirbt man.

Nach dem Gespräch über das weiße Taschentuch klebte ich Oskar Pastior die halbe Nacht eine Collage auf eine weiße Karte:

Hier tanzen Punkte sagt Bea

kommst in ein langstieliges Glas Milch

Wäsche in Weiß graugrüne Zinkwanne

bei Nachnahme entsprechen sich

fast alle Materialien

schau her

ich bin die Zugfahrt und

die Kirsche in der Seifenschale

sprich nie mit fremden Männern und

über die Zentrale

Als ich die Woche darauf zu ihm kam, ihm die Collage schenken wollte, sagte er: Da mußt du noch draufkleben FÜR OSKAR. Ich sagte: Was ich dir gebe, das gehört dir. Du weißt es doch. Er sagte: Du mußt es draufkleben, die Karte weiß es vielleicht nicht. Ich nahm sie wieder mit nach Hause und klebte drauf: Für Oskar. Und schenkte sie ihm die nächste Woche wieder, als wäre ich das erste Mal vom Tor ohne Taschentuch zurückgegangen und jetzt zum zweiten Mal am Tor mit einem Taschentuch.

Mit einem Taschentuch endet auch eine andere Geschichte:

Der Sohn meiner Großeltern hieß Matz. In den 30er Jahren wurde er zur Kaufmannslehre nach Temeswar geschickt, um den Getreidehandel und Kolonialwarenladen der Familie zu übernehmen. An der Schule unterrichteten Lehrer aus dem Deutschen Reich, richtige Nazis. Der Matz war nach der Lehre vielleicht nebenbei auch zum Kaufmann, aber hauptsächlich zum Nazi ausgebildet – Gehirnwäsche nach Plan. Der Matz war nach der Lehre ein glühender Nazi, ein Ausgewechselter. Er bellte antisemitische Parolen, war unerreichbar wie ein Debiler. Mein Großvater hat ihn mehrmals zurechtgewiesen: Er habe sein ganzes Vermögen nur durch Kredite von jüdischen Geschäftsfreunden. Und als das nichts half, hat er ihn mehrmals geohrfeigt. Doch sein Verstand war getilgt. Er spielte den Dorfideologen, drangsalierte Gleichaltrige, die sich vor der Front drückten. Er hatte bei der rumänischen Armee einen Schreibtischposten. Aber aus der Theorie drängte es ihn in die Praxis, er meldete sich freiwillig zur SS, wollte an die Front. Ein paar Monate später kam er nach Hause, um zu heiraten. Von den Verbrechen an der Front belehrt, nutzte er eine gültige Zauberformel, um dem Krieg für ein paar Tage zu entkommen. Diese Zauberformel hieß: Heiratsurlaub.

Meine Großmutter hatte zwei Fotos von ihrem Sohn Matz ganz hinten in einer Schublade, ein Hochzeitsfoto und ein Todesfoto. Auf dem Hochzeitsbild steht eine Braut in Weiß, eine Hand größer als er, dünn und ernst, eine Gipsmadonna. Auf ihrem Kopf ein Wachskranz wie eingeschneites Laub. Neben ihr der Matz in der Naziuniform. Statt ein Bräutigam zu sein, ist er ein Soldat. Ein Heiratssoldat und sein eigener letzter Heimatsoldat. Kaum zurück an der Front, kam das Todesfoto. Darauf ist ein allerletzter, von einer Mine zerfetzter Soldat. Das Todesfoto ist handgroß, ein schwarzer Acker, mittendrauf ein weißes Tuch mit einem grauen Häuflein Mensch. Im Schwarzen liegt das weiße Tuch so klein wie ein Kindertaschentuch, dessen weißes Viereck in der Mitte mit einer bizarren Zeichnung bemalt ist. Für meine Großmutter hatte auch dieses Foto seine Mixtur: auf dem weißen Taschentuch war ein toter Nazi, in ihrem Gedächtnis ein lebender Sohn. Meine Großmutter hatte dieses Doppelbild alle Jahre in ihrem Gebetbuch liegen. Sie betete jeden Tag. Wahrscheinlich waren auch ihre Gebete doppelbödig. Wahrscheinlich folgten sie dem Riß vom geliebten Sohn zum besessenen Nazi und erbaten auch vom Herrgott den Spagat, diesen Sohn zu lieben und dem Nazi zu vergeben.

Mein Großvater war im Ersten Weltkrieg Soldat. Er wußte, wovon er spricht, wenn er in Bezug auf seinen Sohn Matz oft und verbittert sagte: Ja, wenn die Fahnen flattern, rutscht der Verstand in die Trompete. Diese Warnung paßte auch auf die folgende Diktatur, in der ich selber lebte. Täglich sah man den Verstand der kleinen und großen Profiteure in die Trompete rutschen. Ich beschloß, die Trompete nicht zu blasen.

Aber als Kind mußte ich gegen meinen Willen Akkordeon spielen lernen. Denn im Haus stand das rote Akkordeon des toten Soldaten Matz. Die Riemen des Akkordeons waren viel zu lang für mich. Damit sie nicht von der Schulter rutschen, band der Akkordeonlehrer sie mir auf dem Rücken mit einem Taschentuch zusammen.

Kann man sagen, daß gerade die kleinsten Gegenstände, und seien es Trompete, Akkordeon oder Taschentuch, das Disparateste im Leben zusammenbinden. Daß die Gegenstände kreisen und in ihren Abweichungen etwas haben, das den Wiederholungen gehorcht – dem Teufelskreis. Man kann es glauben, aber nicht sagen. Aber was man nicht sagen kann, kann man schreiben. Weil das Schreiben ein stummes Tun ist, eine Arbeit vom Kopf in die Hand. Der Mund wird übergangen. Ich habe in der Diktatur viel geredet, meistens weil ich mich entschlossen hatte, die Trompete nicht zu blasen. Meistens hat das Reden unerträgliche Folgen gehabt. Aber das Schreiben hat im Schweigen begonnen, dort auf der Fabriktreppe, wo ich mit mir selbst mehr ausmachen mußte, als man sagen konnte. Das Geschehen war im Reden nicht mehr zu artikulieren. Höchstens die äußeren Hinzufügungen, aber nicht deren Ausmaß. Dieses konnte ich nur noch stumm im Kopf buchstabieren, im Teufelskreis der Wörter beim Schreiben. Ich reagierte auf die Todesangst mit Lebenshunger. Der war ein Worthunger. Nur der Wortwirbel konnte meinen Zustand fassen. Er buchstabierte, was sich mit dem Mund nicht sagen ließ. Ich lief dem Gelebten im Teufelskreis der Wörter hinterher, bis etwas so auftauchte, wie ich es vorher nicht kannte. Parallel zur Wirklichkeit trat die Pantomime der Wörter in Aktion. Sie respektiert keine realen Dimensionen, schrumpft die Hauptsachen und dehnt die Nebensachen. Der Teufelskreis der Wörter bringt dem Gelebten Hals über Kopf eine Art verwunschene Logik bei. Die Pantomime ist rabiat und bleibt ängstlich, und genauso süchtig wie überdrüssig. Das Thema Diktatur ist von sich aus dabei, weil Selbstverständlichkeit nie mehr wiederkehrt, wenn sie einem fast komplett geraubt worden ist. Das Thema ist implizit da, aber in Besitz nehmen mich die Wörter. Sie locken das Thema hin, wo sie wollen. Nichts mehr stimmt und alles ist wahr.

Als Treppenwitz war ich so einsam wie damals als Kind im Flußtal beim Kühehüten. Ich aß Blätter und Blüten, damit ich zu ihnen gehöre, denn sie wußten, wie man lebt und ich nicht. Ich redete sie mit ihren Namen an. Der Name Milchdistel sollte wirklich die stachelige Pflanze mit der Milch in den Stielen sein. Aber auf den Namen Milchdistel hörte die Pflanze nicht. Ich versuchte es mit erfundenen Namen: STACHELRIPPE, NADELHALS, in denen weder Milch noch Distel vorkam. Im Betrug aller falschen Namen vor der richtigen Pflanze tat sich die Lücke ins Leere auf. Die Blamage, mit mir allein laut zu reden und nicht mit der Pflanze. Aber die Blamage tat mir gut. Ich hütete Kühe und der Wortklang behütete mich. Ich spürte:

Jedes Wort im Gesicht

weiß etwas vom Teufelskreis

und sagt es nicht

Der Wortklang weiß, daß er betrügen muß, weil die Gegenstände mit ihrem Material betrügen, die Gefühle mit ihren Gesten. An der Schnittstelle, wo der Betrug der Materialien und der Gesten zusammenkommen, nistet sich der Wortklang mit seiner erfundenen Wahrheit ein. Beim Schreiben kann von Vertrauen keine Rede sein, eher von der Redlichkeit des Betrugs.

Damals in der Fabrik, als ich ein Treppenwitz und das Taschentuch mein Büro war, habe ich im Lexikon auch das schöne Wort TREPPENZINS gefunden. Es bedeutet in Stufen ansteigende Zinssätze einer Anleihe. Die ansteigenden Zinssätze sind für den Einen Kosten, für den Anderen Einnahmen. Beim Schreiben werden sie beides, je mehr ich mich im Text vertiefe. Je mehr das Geschriebene mich ausraubt, desto mehr zeigt es dem Gelebten, was es im Erleben nicht gab. Nur die Wörter entdecken es, weil sie es vorher nicht wußten. Wo sie das Gelebte überraschen, spiegeln sie es am besten. Sie werden so zwingend, daß sich das Gelebte an sie klammern muß, damit es nicht zerfällt.

Mir scheint, die Gegenstände kennen ihr Material nicht, die Gesten kennen nicht ihre Gefühle und die Wörter nicht den Mund, der spricht. Aber um uns der eigenen Existenz zu versichern, brauchen wir die Gegenstände, die Gesten und die Wörter. Je mehr Wörter wir uns nehmen dürfen, desto freier sind wir doch. Wenn uns der Mund verboten wird, suchen wir uns durch Gesten, sogar durch Gegenstände zu behaupten. Sie sind schwerer zu deuten, bleiben eine Zeitlang unverdächtig. So können sie uns helfen, die Erniedrigung in eine Würde umzukrempeln, die eine Zeitlang unverdächtig bleibt.

Kurz vor meiner Emigration aus Rumänien wurde meine Mutter frühmorgens vom Dorfpolizisten abgeholt. Sie war schon am Tor, als ihr einfiel, HAST DU EIN TASCHENTUCH. Sie hatte keines. Obwohl der Polizist ungeduldig war, ging sie noch mal ins Haus zurück und nahm sich ein Taschentuch. Auf der Wache tobte der Polizist. Das Rumänisch meiner Mutter reichte nicht, um sein Geschrei zu verstehen. Dann verließ er das Büro und schloß die Tür von außen ab. Den ganzen Tag saß meine Mutter eingesperrt da. Die ersten Stunden saß sie an seinem Tisch und weinte. Dann ging sie auf und ab und begann mit dem tränennassen Taschentuch den Staub von den Möbeln zu wischen. Dann nahm sie den Wassereimer aus der Ecke und das Handtuch vom Nagel an der Wand und wischte den Boden. Ich war entsetzt, als sie mir das erzählte. Wie kannst Du dem das Büro putzen, fragte ich. Sie sagte, ohne sich zu genieren, ich habe mir Arbeit gesucht, daß die Zeit vergeht. Und das Büro war so dreckig. Gut, daß ich mir eins von den großen Männertaschentüchern mitgenommen hatte.

Erst jetzt verstand ich, durch zusätzliche, aber freiwillige Erniedrigung verschaffte sie sich Würde in diesem Arrest. In einer Collage habe ich Wörter dafür gesucht:

Ich dachte an die stramme Rose im Herzen

an die nutzlose Seele wie ein Sieb

der Inhaber fragte aber:

wer gewinnt die Oberhand

ich sagte: die Rettung der Haut

er schrie: die Haut ist

nur ein Fleck beleidigter Batist

ohne Verstand

Ich wünsche mir, ich könnte einen Satz sagen, für alle, denen man in Diktaturen alle Tage, bis heute, die Würde nimmt – und sei es ein Satz mit dem Wort Taschentuch. Und sei es die Frage: HABT IHR EIN TASCHENTUCH.

Kann es sein, daß die Frage nach dem Taschentuch seit jeher gar nicht das Taschentuch meint, sondern die akute Einsamkeit des Menschen.

Herta Müller – Conférence Nobel

English

English [pdf]

Swedish

Swedish [pdf]

French

French [pdf]

German

German [pdf]

Spanish

Spanish [pdf]

Le 7 décembre 2009

Chaque mot en sait long sur le cercle vicieux

TU AS UN MOUCHOIR ? me demandait ma mère au portail tous les matins, avant que je ne parte dans la rue. Je n’en avais pas. Étant sans mouchoir, je retournais en prendre un dans ma chambre. Je n’en avais jamais, car tous les jours, j’attendais cette question. Le mouchoir était la preuve que ma mère me protégeait le matin. Le reste de la journée, pour les autres sujets, je me débrouillais seule. La question TU AS UN MOUCHOIR ? était un mot tendre détourné. Direct, il aurait été gênant, ça ne se faisait pas chez les paysans. L’amour était travesti en question. On ne pouvait l’exprimer que sèchement, d’un ton impérieux, comme les gestes du travail. C’était même la brusquerie de la voix qui soulignait la tendresse. Tous les matins, au portail, j’étais d’abord sans mouchoir, et j’attendais d’en avoir un pour m’en aller dans la rue ; c’était comme si, grâce au mouchoir, ma mère avait été présente.

Et vingt ans plus tard, à la ville, j’étais depuis longtemps seule, traductrice dans une usine de construction mécanique. Je me levais à cinq heures et prenais mon travail à six heures et demie. Le matin, diffusé par le haut-parleur, l’hymne national retentissait dans la cour de l’usine. À la pause de midi, c’étaient des chœurs d’ouvriers. Quant aux ouvriers attablés, ils avaient les yeux vides comme du fer-blanc, les mains barbouillées de graisse, et leur casse-croûte était emballé dans du papier journal. Avant de manger leur tranche de lard, ils grattaient l’encre d’imprimerie qui était dessus. Deux années de train-train quotidien s’écoulèrent.

La troisième année marqua la fin de l’égalité des jours. En l’espace d’une semaine, je vis arriver trois fois dans mon bureau, tôt le matin, un géant à la lourde ossature et au regard d’un bleu étincelant : un colosse des services secrets.

La première fois, il m’insulta en restant debout et s’en alla.

La deuxième fois, il enleva sa parka, l’accrocha à la clé du placard et s’assit. Ce matin-là, j’avais apporté des tulipes de chez moi, et je les arrangeais dans le vase. Tout en me regardant, il loua ma singulière expérience de la nature humaine. Il avait une voix onctueuse qui me sembla louche. Je refusai le compliment : je m’y connaissais en tulipes, pas en êtres humains. Il rétorqua d’un air narquois qu’il en savait plus long sur ma personne que moi sur les tulipes. Et il partit, sa parka sur le bras.

La troisième fois, il s’assit et je restai debout, car il avait posé sa serviette sur ma chaise. Je n’osai pas la mettre par terre. Il me traita d’idiote finie, de fainéante, de femme facile, aussi infecte qu’une chienne errante. Il repoussa le vase au bord du bureau et, au milieu, posa un crayon et une feuille de papier. Il hurla : écrivez ! Debout, j’écrivis sous sa dictée mon nom, ma date de naissance et mon adresse. Puis : quel que soit le degré de proximité ou de parenté, je ne dirai à personne que je … et voici l’affreux mot roumain : colaborez, que je collabore. Ce mot, je ne l’écrivis pas. Je posai le crayon, allai à la fenêtre et regardai, au dehors, la rue poussiéreuse. Elle n’était pas asphaltée, elle avait des nids-de-poule et des maisons bossues. Cette ruelle délabrée s’appelait toujours Strada Gloriei, rue de la Gloire. Un chat était juché sur un mûrier tout dépouillé, rue de la Gloire. C’était le chat de l’usine, celui à l’oreille déchirée. Au-dessus de lui, un soleil matinal, comme un tambour jaune. Je fis : n-am caracterul. Je n’ai pas ce caractère-là. Je le dis à la rue, dehors. Le mot “caractère” exaspéra l’homme des services secrets. Il déchira la feuille et jeta les bouts de papier par terre. Mais à l’idée qu’il devrait présenter à son chef cette tentative de recrutement, il se baissa et ramassa tous les morceaux qu’il flanqua dans sa serviette. Puis il poussa un gros soupir et, dans sa déconfiture, lança le vase de tulipes contre le mur : il s’y fracassa, et on entendit comme un grincement de dents en plein vol. La serviette sous le bras, il marmonna : tu le regretteras, on te noiera dans le fleuve. Je fis en aparté : si je signe ça, je ne pourrai plus vivre avec moi-même, donc j’en viendrai là. Autant que vous vous en chargiez. La porte du bureau étant déjà ouverte, il était parti. Dehors, dans la Strada Gloriei, le chat de l’usine avait sauté de l’arbre sur le toit de la maison. Une branche se balançait comme un trampoline.

Le lendemain, les tracasseries commencèrent. On voulait que je quitte définitivement l’usine. Tous les matins à six heures et demie, je devais me présenter chez le directeur. Et à chaque fois, il y avait dans son bureau le chef du syndicat et le secrétaire du Parti. Comme ma mère avec sa question d’autrefois tu as un mouchoir ?, le directeur me demandait tous les matins : tu as trouvé un nouveau travail ? Je répondais régulièrement : je n’en cherche pas, je me sens bien à l’usine, je voudrais y rester jusqu’à la retraite.

Un matin, à mon arrivée, je trouvai mes gros dictionnaires par terre dans le couloir, devant la porte de mon bureau. J’ouvris, c’était un ingénieur qui l’occupait. Il dit : ici, on frappe avant d’entrer. C’est moi qui suis là, tu n’as rien à y faire. Je ne pouvais pas rentrer à la maison : il ne fallait pas leur fournir ce prétexte, on m’aurait licenciée pour cause d’absence injustifiée. Je n’avais plus de bureau, mais il fallait à tout prix que je vienne travailler normalement tous les jours, il était hors de question de manquer.

Les premiers temps, mon amie me libéra un coin de son bureau – à chaque fois je lui racontais tout, en rentrant par la misérable Strada Gloriei. Jusqu’au matin où, postée à l’entrée de son bureau, elle déclara : je n’ai pas le droit de te laisser entrer. Tout le monde dit que tu es une balance. Désormais, les tracasseries venaient d’en bas, c’étaient des rumeurs qui circulaient parmi les collègues. Et ça, c’était le pire. On peut se défendre contre des attaques, mais face aux calomnies, on est impuissant. Jour après jour, dans mes calculs, je ne donnais pas cher de ma peau. Mais la perfidie, je n’en venais pas à bout. Mes calculs ne la rendaient pas supportable. La calomnie vous couvre de boue et on étouffe, faute de pouvoir se défendre. Dans l’esprit de mes collègues, j’étais précisément ce que j’avais refusé d’être. Si je les avais espionnés, ils auraient eu une confiance aveugle en moi. Au fond, ils me punissaient de les avoir épargnés.

Comme je ne devais surtout pas être absente, même si je n’avais plus de bureau et que mon amie ne me prêtait plus le sien, je traînais dans la cage d’escalier sans savoir que faire. Je montais et descendais les marches. Et tout à coup, je redevins l’enfant de ma mère, car J’AVAIS UN MOUCHOIR. Je le posai sur une marche entre le premier et le deuxième étage, le lissai bien comme il faut, et m’assis dessus. Mes gros dictionnaires sur les genoux, je me mis à traduire des descriptions de machines hydrauliques. J’avais l’esprit de l’escalier, et un mouchoir en guise de bureau. À l’heure du déjeuner, mon amie venait s’asseoir à côté de moi. Nous mangions ensemble, comme nous l’avions fait dans son bureau et, auparavant, dans le mien. Depuis le haut-parleur de la cour, les chœurs d’ouvriers chantaient comme toujours le bonheur du peuple. Tout en mangeant, mon amie se lamentait sur mon sort, à ma différence. Moi, je devais rester forte pendant longtemps. Quelques semaines interminables, jusqu’au licenciement.

Ayant l’esprit de l’ESCALIER, je cherchai ce mot dans le dictionnaire pour savoir de quoi il retournait : la marche du bas est dite de DÉPART, celle du haut est la marche PALIÈRE. La partie horizontale sur laquelle on pose le pied s’appelle le GIRON, et la partie en saillie sur le nu de la contremarche est le NEZ. Le COLLET, c’est le petit côté d’une marche. Grâce aux pièces des machines-outils hydrauliques et barbouillées de graisse, je connaissais déjà les jolis termes que sont QUEUE D’ARONDE, COL DE CYGNE ; sur un tour, c’était la VIS-MÈRE qui soutenait les vis. Et j’étais tout aussi fascinée par la beauté de la langue technique, par les noms poétiques désignant les parties de l’escalier. NEZ, COLLET : l’escalier avait par conséquent un visage. Qu’est-ce qui pousse donc l’être humain à intégrer son propre visage même aux objets les plus encombrants, qu’ils soient en bois, en pierre, en béton ou en fer, et à donner à un outillage inanimé le nom de sa propre chair, à le personnifier en y voyant des parties du corps ? Les spécialistes d’une technique ont-ils besoin de cette tendresse cachée pour rendre supportable un travail ardu ? Est-ce que chaque travail, dans n’importe quel métier, obéit au même principe que la question de ma mère sur le mouchoir ?

Quand j’étais petite, à la maison, il y avait un tiroir à mouchoirs avec deux rangées comportant chacune trois piles :

À gauche, les mouchoirs d’homme pour mon père et mon grand-père.

À droite, les mouchoirs de femme pour ma mère et ma grand-mère.

Au milieu, les mouchoirs d’enfant pour moi.

Ce tiroir était notre portrait de famille, en format mouchoir de poche. Les mouchoirs d’homme, les plus grands, avaient sur le pourtour des rayures foncées en marron, gris ou bordeaux. Ceux de femme étaient plus petits, avec un liseré bleu clair, rouge ou vert. Encore plus petits et sans liseré, ceux d’enfant formaient un carré blanc orné de fleurs ou d’animaux. Dans chaque catégorie de mouchoirs, il y avait ceux pour tous les jours, sur le devant, et ceux du dimanche, au fond. Le dimanche, le mouchoir devait être assorti aux vêtements, même si on ne le voyait pas.

À la maison, le mouchoir comptait plus que tout, et même plus que nous. Il était d’une utilité universelle en cas de rhume, saignement de nez, écorchure à la main, au coude ou au genou, il servait à essuyer les larmes ou, si on le mordait, à les retenir. Contre la migraine, on appliquait sur le front un mouchoir imbibé d’eau froide. Noué aux quatre coins, il protégeait la tête des insolations ou de la pluie. Pour ne pas oublier quelque chose, on y faisait un nœud en guise de pense-bête. Pour porter un sac lourd, on enroulait son mouchoir autour de sa main. On l’agitait en signe d’adieu, au départ du train. Et comme “train” se dit TREN en roumain et que le mot “larme” se dit TRÄN en dialecte du Banat, le grincement des roues sur les rails m’a toujours fait penser aux pleurs. Dans mon village, quand quelqu’un mourait chez soi, on lui nouait aussitôt un mouchoir autour du menton pour maintenir la bouche fermée jusqu’à la rigidité cadavérique. Et si quelqu’un, étant sorti, tombait à la renverse au bord du chemin, il y avait toujours un passant pour lui couvrir le visage de son mouchoir – là, le mouchoir était le premier repos du mort.

En été, les jours de canicule, les parents envoyaient leurs enfants au cimetière arroser les fleurs en fin de soirée. Par groupes de deux ou trois, nous allions de tombe en tombe, en arrosant vite. Puis, bien serrés contre les autres sur les marches de la chapelle, nous regardions les traînées de vapeur qui montaient de la plupart des tombes. Elles volaient quelque temps dans l’air noir et disparaissaient. Pour nous, c’étaient les âmes des morts : des silhouettes d’animaux, des lunettes, des fioles et des tasses, des gants et des chaussettes. Et, çà et là, un mouchoir blanc avec le noir liseré de la nuit.

Plus tard, j’eus des entretiens avec Oskar Pastior pour écrire mon livre sur sa déportation dans un camp de travail soviétique, et il me raconta qu’une vieille mère russe lui avait donné un mouchoir de batiste. Peut-être que vous aurez de la chance, mon fils et toi, et que vous pourrez bientôt rentrer chez vous, avait dit la Russe. Son fils avait l’âge d’Oskar Pastior et il était tout aussi éloigné de sa maison, mais dans une autre direction, selon elle, dans un bataillon pénitentiaire. Mendiant à demi mort de faim, Oskar Pastior avait frappé à sa porte ; il voulait échanger un boulet de charbon contre un peu de nourriture. Elle le laissa entrer, lui donna une soupe bien chaude, et comme il avait le nez qui coulait dans l’assiette, ce mouchoir blanc de batiste n’ayant jamais servi. Avec son bord ajouré, ses faisceaux et ses rosettes méticuleusement brodés au fil de soie, ce mouchoir était d’une beauté qui étreignit le mendiant tout en le blessant. Cet objet ambigu était, d’une part, un réconfort en batiste, et, d’autre part, un centimètre aux bâtonnets de soie, petits traits blancs sur la graduation de la déchéance. Pour cette femme, Pastior était lui-même un être ambigu, entre mendiant détaché du monde et enfant perdu dans le monde. Double personnage, il fut comblé et dépassé par le geste d’une femme qui, elle-même, était à ses yeux deux personnes : une étrangère et une mère aux petits soins demandant TU AS UN MOUCHOIR ?

Depuis que je connais cette histoire, j’ai moi aussi une question : la phrase TU AS UN MOUCHOIR est-elle universellement valable, s’étend-elle sur la moitié du monde, dans le scintillement de la neige, des frimas au dégel ? Franchit-elle toutes les frontières, entre les monts et les steppes, pour entrer dans un immense empire parsemé de camps pénitentiaires et de camps de travail ? Reste-t-elle increvable, cette question, malgré le marteau et la faucille, ou même tous les camps de rééducation sous Staline ?

J’ai beau parler roumain depuis des lustres, c’est en m’entretenant avec Oskar Pastior que j’ai pris conscience, pour la première fois, que “mouchoir” se dit en roumain BATISTÀ. Encore la sensualité de cette langue roumaine qui, avec une simplicité absolue, envoie ses mots au cœur des choses. La matière ne fait pas de détours, elle se désigne comme un mouchoir déjà confectionné, BATISTÀ, à croire que tous les mouchoirs du monde sont toujours en batiste …

Oskar Pastior a conservé dans son paquetage cette relique d’une double mère ayant un double fils, et il l’a rapportée chez lui au bout de cinq années passées au camp. Pourquoi ? Son mouchoir blanc était l’espoir et la peur. Abandonner l’espoir ou la peur, c’est mourir.

Après cette conversation sur le mouchoir de batiste, je fis pour Oskar Pastior un collage sur une carte blanche, jusque tard dans la nuit.

Ici dansent des points, dit Bea

tu entres dans un verre à pied de lait

linge blanc cuve en zinc vert-de-gris

contre remboursement s’accordent

presque toutes les matières

regarde par là

je suis le trajet en train et

la cerise dans le porte-savon

ne parle jamais aux étrangers ni

de la centrale

La semaine d’après, quand je suis venue le voir pour lui offrir le collage, il m’a dit : il faut que tu rajoutes : POUR OSKAR. J’ai répondu : ce que je te donne t’appartient, tu le sais bien. Et il a fait : il faut que tu le mettes dessus, la carte ne le sait peut-être pas. Je l’ai rapportée chez moi, et j’y ai ajouté : POUR OSKAR. Je la lui ai redonnée la semaine d’après, comme si, arrivée au portail sans mouchoir, j’étais retournée en chercher un.

C’est encore par un mouchoir que se termine une autre histoire.

Le fils de mes grands-parents s’appelait Matz. Dans les années trente, on l’envoya en apprentissage à Timisoara pour qu’il reprenne l’épicerie familiale où l’on vendait aussi des grains. À l’école, il y avait des professeurs venus du Reich allemand, de vrais nazis. Cet apprentissage a fait de Matz un vague commerçant et surtout un nazi, par un lavage de cerveau planifié. Nouvelle recrue, Matz était fanatique au terme de son apprentissage. Il aboyait des slogans antisémites, l’air absent, comme un débile mental. Mon grand-père lui a sonné les cloches plusieurs fois, en lui rappelant que toute sa fortune venait de prêts consentis par des amis juifs qui étaient dans les affaires. Il lui est même arrivé de gifler son petit-fils qui ne voulait rien entendre. Matz n’avait plus sa tête : il jouait à l’idéologue rural et martyrisait les tire-au-flanc de son âge qui refusaient de partir pour le front. Il avait un emploi de bureau dans l’armée roumaine. Mais, quittant la théorie pour passer à la pratique, il s’engagea comme volontaire dans la SS ; il voulait monter au front. Quelques mois plus tard, il revint chez lui pour se marier. Échaudé par les crimes vus au front, il se servit d’une formule magique qui fonctionnait, afin d’échapper à la guerre durant quelques jours. Cette formule était la permission pour mariage.

Tout au fond d’un tiroir, ma grand-mère avait deux photos de son fils Matz, une photo de mariage et une photo de décès. Sur la photo de mariage, une mariée en blanc, grave et fine, le dépasse d’un empan, une madone en plâtre portant sur la tête une couronne en fleurs de cire comme enneigées. À côté d’elle, Matz en uniforme nazi. Un soldat, et non un marié. L’hymen et l’hymne à la patrie d’un dernier soldat. À peine était-il reparti au front que sa photo de décès arriva, montrant un soldat, le dernier des derniers, déchiqueté par une mine. Cette photo a la taille d’une main : un champ noir avec, au beau milieu, un drap blanc, et dessus, un tas humain de couleur grise. Sur fond noir, ce drap blanc a la taille d’un mouchoir d’enfant avec, au milieu du carré blanc, un drôle de dessin. Pour ma grand-mère, cette photo était encore celle d’une dualité : sur le mouchoir blanc, il y avait un nazi mort, et dans sa mémoire, un fils vivant. Au fil des ans, elle a gardé ce double portrait dans son missel. Elle priait tous les jours, et ses prières devaient être ambiguës, elles aussi. Il faut croire que, suivant la faille d’un fils aimé devenu nazi forcené, elles demandaient au Seigneur d’exécuter le même grand écart, d’aimer ce fils et de pardonner au nazi.

Mon grand-père avait été soldat pendant la Première Guerre mondiale. Il savait de quoi il parlait, quand il répétait amèrement, au sujet de son fils Matz : hé oui, dès qu’on agite le drapeau, le bon sens dérape et file dans la trompette. Cette mise en garde visait aussi la dictature dans laquelle j’ai vécu ensuite. Des profiteurs, petits ou gros, on en voyait tous les jours avoir la raison qui filait dans la trompette. Quant à moi, je décidai de ne pas claironner.

On me força tout de même, quand j’étais petite, à jouer de l’accordéon, car à la maison, il y avait l’accordéon rouge de Matz, le soldat défunt. Comme les bretelles étaient trop longues pour moi, mon professeur d’accordéon me les attachait dans le dos avec un mouchoir pour les empêcher de glisser sur l’épaule.

Autant dire que les moindres objets, même une trompette, un accordéon ou un mouchoir, relient ce que la vie a de plus disparate : les objets décrivent des cercles et, jusque dans leurs écarts, ils ont tendance à se conformer à la répétition, au cercle vicieux. On peut le croire, mais pas le dire. Et ce qui est impossible à dire peut s’écrire, puisque l’écriture est un acte muet, un travail partant de la tête pour aller vers la main, en évitant la bouche. Sous la dictature, j’ai beaucoup parlé, surtout parce que j’avais décidé de ne pas claironner. Mes paroles ont presque toujours eu des conséquences insoutenables. Mais l’écriture a commencé par le silence, dans cet escalier d’usine où, livrée à moi-même, j’ai dû tirer de moi davantage que la parole ne le permettait. La parole ne pouvait plus exprimer ce qui se passait. Elle faisait à la rigueur des ajouts adventices, sans évoquer leur portée. Cette dernière, je n’avais d’autre ressource que de l’épeler en silence dans ma tête, dans le cercle vicieux des mots, lorsque j’écrivais. Face à la peur de la mort, ma réaction fut une soif de vie. Une soif de mots. Seul le tourbillon des mots parvenait à formuler mon état. Il épelait ce que la bouche n’aurait su dire. Dans le cercle vicieux des mots, je talonnais le vécu jusqu’à ce qu’apparaisse une chose que je n’avais pas connue sous cette forme. Parallèle à la réalité, la pantomime des mots entre en action. Loin de respecter les dimensions réelles, elle diminue l’essentiel et amplifie ce qui est accessoire. Le cercle vicieux des mots prend ses jambes à son cou, il enseigne au vécu une sorte de logique enchantée. Sa pantomime est à la fois furieuse et anxieuse, et tout aussi avide que blasée. Le thème de la dictature entre en jeu de son propre chef, car l’évidence ne reviendra plus jamais : chacun en a été entièrement spolié ou peu s’en faut. Cette thématique est présente de façon implicite, mais ce sont les mots qui prennent possession de moi. Et ils entraînent le thème où bon leur semble. Plus rien ne va comme de juste et tout est vrai.

Dans mon escalier, j’étais aussi seule qu’à l’époque où je gardais les vaches dans la vallée. Je mangeais des feuilles et des fleurs pour être des leurs, puisqu’elles savaient comment vivre et que je l’ignorais. Je les appelais par leur nom. Celui de chardon laiteux devait bien désigner cette plante épineuse aux tiges pleines de lait, sauf que la plante ne répondait pas au nom de chardon laiteux. Je tentai le coup avec des noms inventés, ÉPINECÔTE, COUDAIGUILLE, ne comportant ni lait, ni chardon. Dans cette supercherie de tous les faux noms de la vraie plante, la lacune débouchait sur un vide béant, la honte de parler toute seule et non avec la plante. Mais cette honte me faisait du bien. Gardée par la sonorité des mots, je gardais les vaches.

Chaque mot dans la figure

en sait long sur le cercle vicieux

et ne le dit pas

La sonorité des mots sait qu’elle doit tromper, puisque les objets trichent sur leur matière, les sentiments sur leurs gestes. À l’intersection où convergent la tromperie des matières et celle des gestes vient se nicher la sonorité avec sa vérité forgée de toutes pièces. Dans l’écriture, il ne saurait être question de confiance, mais plutôt d’une franche tromperie.

À l’usine, quand j’étais la mauvaise blague qu’on lâche dans l’escalier, avec un mouchoir pour tout bureau, j’ai aussi trouvé dans le dictionnaire le beau mot d’ÉCHELONNEMENT. Il signifie que les intérêts d’un prêt augmentent par paliers, en gravissant des échelons. Ces intérêts croissants sont pour l’un des débours, et pour l’autre des rentrées. Dans l’écriture, ce sont les deux, à mesure que je me plonge dans le texte. Plus l’écrit me dévalise, plus il montre au vécu ce qu’il n’y avait pas dans ce qu’on vivait. Seuls les mots le découvrent, vu qu’ils ne le savaient pas auparavant. C’est lorsqu’ils surprennent le vécu qu’ils le reflètent le mieux. Ils deviennent si concluants que le vécu doit s’agripper à eux pour ne pas se désintégrer.

À mon sens, les objets ne connaissent pas leur matière, et les gestes ignorent leurs sentiments, comme les mots ignorent la bouche qui les dit. Mais pour nous convaincre de notre propre existence, nous avons besoin d’objets, de gestes et de mots. Plus nous pouvons prendre de mots, plus nous sommes libres, tout de même. Quand notre bouche est mise à l’index, nous tentons de nous affirmer par des gestes, voire des objets. Plus malaisés à interpréter, ils n’ont rien de suspect, pendant un temps. Ils peuvent nous aider à convertir l’humiliation en une dignité qui, pendant un temps, n’a rien de suspect.

Peu avant que je n’émigre de Roumanie, le policier du village est venu arrêter ma mère, au petit matin. Arrivée au portail, la voilà qui se dit tout à coup : TU AS UN MOUCHOIR ? Elle n’en avait pas. L’agent avait beau être impatient, elle est retournée en chercher un. Une fois au poste, le policier a tempêté, mais ma mère ne savait pas assez le roumain pour comprendre ses vociférations. Il a quitté le bureau en verrouillant la porte de l’extérieur. Ma mère est restée enfermée toute la journée : les premières heures, elle a pleuré, assise à la place du policier, puis elle a fait les cent pas, et s’est mise à dépoussiérer les meubles avec son mouchoir mouillé de larmes. Ensuite, elle a pris un seau d’eau dans un coin, un essuie-mains accroché à un clou, et elle a lavé le sol. En l’entendant me le raconter, j’ai été horrifiée : comment ça, tu as nettoyé le bureau de ce type ? Elle a répondu, nullement gênée : je devais m’activer pour passer le temps. Et puis, c’était tellement crasseux … Heureusement que j’avais emporté un grand mouchoir d’homme !

À ce moment-là, j’ai compris que cette humiliation supplémentaire, mais délibérée, lui avait permis de garder sa dignité lors de son arrestation. Dans un de mes collages, j’ai cherché des mots pour rendre cela :

Je pensais à la vigoureuse rose du cœur

à l’âme infructueuse comme une passoire

mais le propriétaire demanda :

qui prend le dessus

je dis : sauver sa peau

il cria : la peau n’est

qu’une tache une batiste offensée

dénuée de bon sens

Pour ceux que la dictature prive de leur dignité tous les jours, jusqu’à aujourd’hui, je voudrais pouvoir dire ne serait-ce qu’une phrase comportant le mot “mouchoir”. Leur demander simplement : AVEZ-VOUS UN MOUCHOIR ?

Se peut-il que cette question, de tout temps, ne porte nullement sur le mouchoir, mais sur la solitude aiguë de l’être humain …

Traduction par Claire de Oliveira

Herta Müller – Nobel Lecture

Herta Müller delivered her Nobel Lecture, 7 December 2009, at the Swedish Academy, Stockholm. She was introduced by Peter Englund, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy. The lecture was delivered in German.

Herta Müller delivered her Nobel Lecture, 7 December 2009, at the Swedish Academy, Stockholm. She was introduced by Peter Englund, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy. The lecture was delivered in German.

English

English [pdf]

Swedish

Swedish [pdf]

French

French [pdf]

German

German [pdf]

Spanish

Spanish [pdf]

December 7, 2009

Every word knows something of a vicious circle

DO YOU HAVE A HANDKERCHIEF was the question my mother asked me every morning, standing by the gate to our house, before I went out onto the street. I didn’t have a handkerchief. And because I didn’t, I would go back inside and get one. I never had a handkerchief because I would always wait for her question. The handkerchief was proof that my mother was looking after me in the morning. For the rest of the day I was on my own. The question DO YOU HAVE A HANDKERCHIEF was an indirect display of affection. Anything more direct would have been embarrassing and not something the farmers practiced. Love disguised itself as a question. That was the only way it could be spoken: matter-of-factly, in the tone of a command, or the deft maneuvers used for work. The brusqueness of the voice even emphasized the tenderness. Every morning I went to the gate once without a handkerchief and a second time with a handkerchief. Only then would I go out onto the street, as if having the handkerchief meant having my mother there, too.

Twenty years later I had been on my own in the city a long time and was working as a translator in a manufacturing plant. I would get up at five a.m.; work began at six-thirty. Every morning the loudspeaker blared the national anthem into the factory yard; at lunch it was the workers’ choruses. But the workers simply sat over their meals with empty tinplate eyes and hands smeared with oil. Their food was wrapped in newspaper. Before they ate their bit of fatback, they first scraped the newsprint off the rind. Two years went by in the same routine, each day like the next.

In the third year the routine came to an end. Three times in one week a visitor showed up at my office early in the morning: an enormous, thick-boned man with sparkling blue eyes—a colossus from the Securitate.

The first time he stood there, cursed me, and left.

The second time he took off his windbreaker, hung it on the key to the cabinet, and sat down. That morning I had brought some tulips from home and arranged them in a vase. The man looked at me and praised me for being such a keen judge of character. His voice was slippery. I felt uneasy. I contested his praise and assured him that I understood tulips, but not people. Then he said maliciously that he knew me better than I knew tulips. After that he draped his windbreaker over his arm and left.