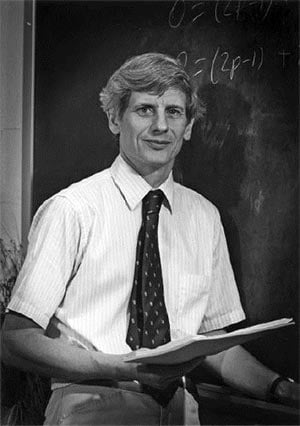

Transcript from an interview with J. Michael Kosterlitz

Interview with J. Michael Kosterlitz on 6 December 2016, during the Nobel Week in Stockholm, Sweden.

Michael Kosterlitz, welcome to Nobel Week. And you brought some artefacts for the museum, what did you bring?

Michael Kosterlitz: I brought some things representing my two passions in life, or my two passions in life at the time. Which are one rock-climbing guide to big cliff in North Wales, and some old calculations on something, that unfortunately is not what I got the prize for, but one of the few hand read notes that we could find, after I had done a major clear-out. That was, what, 40 years ago or something, so of course, it’s had a few clean-outs since. And old scribbled notes which may be of some value, should I become famous. But at the time, the idea of becoming famous was just ridiculous, so it all went.

And the rock-climbing guide, you used to be a very avid rock climber?

Michael Kosterlitz: Yes, I have two greater passions in life; well, probably in order my passions in life were first rock climbing, second physics and third family.

You are awarded the prize this year for absolute first research that you did, coming into the field that you now work in. Can you tell me a bit about how that came about?

Michael Kosterlitz: I was doing high-energy physics and doing lots of elaborate calculations for no return. Then, I was a post-doc in Italy, and of course I needed another job, so the plan was to go to CERN in Geneva, but I failed to get the paperwork in on time, as is my standard procedure, and ended up at Birmingham university, because that was one of the few places from which I got an offer at the very late stage in the game. Birmingham was actually the last place I wanted to go, but it turned out to be the best move I ever made. Because it was there that I met David Thouless and we started working on this problem. Mind you at the time, as far as I was concerned, it was just an entertaining theoretical problem, no more. I had no conception that this could turn in to something big, no idea at all. I doubt that either of us had. It wasn’t until, probably about the 80ies at the earliest, that I realised that we had done something good.

So, in this time after you had done your research, until the time that you really realised what it had led to, did you think about changing fields again, or moving to other parts within physics?

Michael Kosterlitz: Well, I did change fields; I started working on what is called non-equilibrium problems, in other words, on systems which aren’t in thermal equilibrium. And I was hoping to do something as good, when I realised that the work I had done, David and I had done, was actually good work. And I was trying to do something as good in another field but, never managed.

Have you moved back to this field again, is this what you are working on right now?

Michael Kosterlitz: I haven’t moved back, because I haven’t really thought about the field for a long time. And there’s lots of other people work in the field, and are way ahead, you know, have developed it much further. And so, I am, I guess you could call it, one of the ‘grand old men’ of the field, who has trotted out from time to time to say some deep words about it. But beyond that I don’t really do much in the way of research in that field.

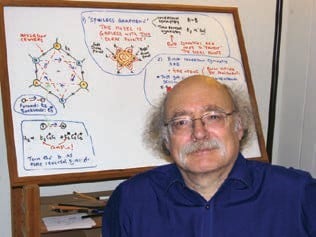

You work with topological changes and phase transitions. When the prize was presented, the Royal Academy brought out some different type of baked goods. Can you try to give us a bit of overview why this would be a useful image?

Michael Kosterlitz: Ok, I’ll try. Let me start by saying that topology is a mathematical subject, which is concerned with the shapes of materials. Not the detailed shapes, because after all, as far as topology is concerned, a plane, you know, a flat surface, is equivalent to a sphere, which is equivalent to any shape you like. All that topology is interested in is the number of holes in the system. It’s a classification of shapes which can be continuously deformed into each other.

Right. You can’t have a half of a hole?

Michael Kosterlitz: Right. I mean, the rules are, you can’t get rid of a hole. Once a hole is there, you can’t get rid of it. Or you can’t make a new hole. Now the connection to what we did is a bit of a stretch, but the idea is that if you take your film of superfluid helium on a nice, flat surface – of course there are no holes in this surface. You say to yourself, what on earth has topology got to do with this? Well, in this context it doesn’t, but there are excitations in films of helium, where the fluid circles round and round a point. These are called vortices. And these excitations do exist, and it turns out they are quite important.

This is where topology comes in; because the surface of the manifold of which the topology is defined, is this layer of superfluid, not the actual thing that it is supported on. And so, if you got a vortex, where the fluid is spinning round and round, near the centre of the vortex, the velocity of the fluid has to divert; go to infinity. Which means that the material can’t be superfluid there, so that is going to hole. So, in other words, if you have a vortex produced, for whatever reason, the topology of the system changes.

Right, so you get these topological changes even in this type of material.

Michael Kosterlitz: Yes.

Was that an intuitive leap, I mean, when you first thought of this idea? Because coming from the outside, it seems as two quite disparate things. Was it intuitive to you that this was a mathematical model that could be used?

Michael Kosterlitz: Not directly. Because to me the physics was all in the various excitations that can occur. So, it is obvious that if you like, well we didn’t know it before we worked on this, that a vortex in superfluid helium, the centre of the vortex, was either empty, nothing there, or it was a normal fluid, not superfluid. So that part of it is simple. And so, I myself came from this point of view; I was only interested in the excitations, topology I didn’t know a thing about. Of course, I had the advantage of working with David Thouless, who seemed to know everything about everything. So, he realised that this was, you know, he used the word topology. And once he explained what topology meant, to me it suddenly became obvious. Call it topology or not, it didn’t really matter, but it sounded like a nice way to talk about it, so we called it ‘topological excitation’.

Are you surprised of how much this field has grown since you’ve worked in it?

Michael Kosterlitz: I am amazed. Because there are so many … The original papers are referred to so often it’s almost embarrassing. I knew that we both knew very well, that the same ideas could be applied to talking about two-dimensional crystals, at least the melting of two-dimensional crystals. Because the essential excitations that melted the crystal, you can call them dislocations if you wish, which are analogous to vortices in superfluid helium. That is as far as we went with the two-dimensional melting. You can work anything out, at least I did a calculation which didn’t go anywhere, because we made the assumption that the lattice structure didn’t matter. Then we also knew that in principle it could be applied to a superconducting film. So, given an estimate of what the critical temperature should be and so on.

But we never really took it seriously, because our argument was that you couldn’t have true superconductivity in thin films. Which is a correct argument, but we never thought about the question of how, what length scales superconductivity could exist. In turns out that experimentally, if you have a system of, let’s say, a centimetre, you know linear size a centimetre or so, which is big by experimental standards, then, as far as, this system should obey the standard vortex theory, and the cut off that is inherent in superconductivity is irrelevant, because it’s of the order of a centimetre as well.

So, are there any of these, I mean, there a number of proposed practical applications for this work. And sort of, moving on looking into the future, are there any applications that you are especially looking forward to seeing?

Michael Kosterlitz: Oh yes! Oh yes yes yes. Because the hope is that the applications in quantum mechanical systems will eventually lead to this magic quantum computer. And I’ll be waiting for my desktop quantum computer. I hope to get one before I die, but I think that perhaps I shouldn’t hold my breath and wait and expect to get one. But anyway, with the developments in quantum mechanics, related to our ideas, it’s starting to look like a quantum computer may not be such a pie dream as I originally thought.

Looking at your career as a scientist, is there any person that really has inspired you, in your work or in your life?

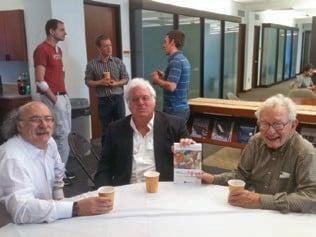

Michael Kosterlitz: Lots of people. My co-worker David Thouless. I first met him as a London graduate in Cambridge and Oxford around 1961, something like that. And he was teaching us, and it was ‘mathematics for scientists’ or something like that. And as soon as he started lecturing, I realised I am in presence of a mind that operates in a different level to mine, and probably most other people. So, of course, I was incredibly happy to collaborate with David, because collaborating with somebody with a mind like that, is just an amazing experience.

Then there are other people who have certainly influenced me greatly. There is Michael Fischer at Cornell, who taught me, I was a post-doc there, back in, when was it 1973-74, who taught me about phase transitions and critical phenomena and the importance of experimental work and how theories and experiments should collaborate and criticise each other. Then there was John Reppy, also Cornell, also a superb experimentalist, and who is responsible for the experimental verification of our theory. So, I guess there are all sorts of people who influenced my thinking and my career. But the most important ones happened early in my life. And the most important one is of course David Thouless.

A bit more personal question; I know you have been diagnosed with MS some time ago. How did you, what did you do? And how did you sort of overcome, and handle something like that?

Michael Kosterlitz: I didn’t really manage to handle it very well at all, because at the time, as I said earlier, my major obsession, and a big part of my life, was mountain climbing. And that I had to quit because I couldn’t do it anymore. It is not easy to continue when half your life is just cut, you know you have no choice but to cut it out. I had a great deal of difficulty in coming to terms with my disability. However, fortunately, as my neurologist likes to say, I’m his star patient, so I did… My version of MS is at least one of these, going to the big remission where I come back almost to the level that I was before the attack. So eventually I managed to replace my passion for mountaineering with other things, and now I do work a lot and I travel a lot. And fortunately, I’ve got a very valuable wife who supports me whatever I feel like doing. And keeps on insisting ‘Look Michael, you can do it – its not as bad as you think, you can do it’. That is very important to me.

A final question; you’ve said earlier that coming into the field that you were awarded the prize for, one of the crucial things was your total ignorance of the details of that field. What do you mean by that, what do you mean when you say that?

Michael Kosterlitz: Exactly what I said. Because, I was a high-energy physicist. And so, my graduate work at Oxford was all in high-energy physics, and I simply went to the required lectures and so on, and something called statistical mechanics, which I sort of ‘mm’ it was one of these model, rather difficult subjects, where it wasn’t part of my chosen research. I didn’t pay much attention to it. But statistical mechanics is the central tool of condensed-matter physics, so when I went to this problem with David Thouless, changed from high-energy to condensed-matter, then statistical mechanics became very important.

And was it important for you to sort of look at the problem with sort of unconventional eyes, or…?

Michael Kosterlitz: Well sure, oh yes! Because, if you knew too much about it, if you were a normal person like me, you wouldn’t even go into the field because there are plenty of rigorous theorems, which were interpreted, is meaning that in that in systems like thin films of helium, two-dimensional crystals couldn’t exist. And there’s nothing wrong with the theorem, it’s just the interpretation of the theorem that was wrong. So David, who knew about these things, realised that it was just the interpretation that was wrong. Me, I was so stupid and ignorant that I said, I had no idea that this lack of long-range order was a serious problem. And so, I went ahead and basically looked at the problem in a different way, and it worked out.

Thank you so much for your time.

Michael Kosterlitz: You’re welcome.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Transcript from an interview with F. Duncan M. Haldane

Interview with F. Duncan M. Haldane on 6 December 2016, during the Nobel Week in Stockholm, Sweden.

Duncan Haldane, welcome to Nobel Week in Stockholm

Duncan Haldane: Thank you.

I noticed that you brought an artefact for the museum, what is it?

Duncan Haldane: Well, when I initiated the work, which this prize was given for, one of the two works which I received this prize for took a long time for to be published, because it was actually contradicting conventional wisdom at the time. Perhaps I didn’t explain it clearly enough, but in any case, this paper was rejected by a number of journals. And in fact, the original arguments which I discovered that magnetic chains had what we now know is a topological phase, when the quantum spin with an integer-spin, but not a half-integer-spin, which was … no one had thought that was an important feature. Why I discovered this really accidentally, I mean I, as a consequence of another piece of work I had done earlier. And it turned out that people’s understanding of magnetic chains was confused and that there were two sources of it.

One was kind of that semiclassical picture that thought of spins like little compasses, little arrows, that pointed and wanted to be parallel/antiparallel. And that works very well in high dimensions when long-range order occurs at low temperatures. But it was actually when it had been known mathematically that a one-dimensional chain, a very long, thin chain of atoms couldn’t, it ought to be destroyed by quantum mechanical fluctuations at any finite temperature, but also at zero temperature. On the other hand, there was a mathematically exact solution of a toy model, that Hans Bethe had discovered, before he went on to, you know, do huge work in understanding why the sun, how the sun works, and working on nuclear energy. But his early work on magnetic chains had this interesting solution which he guessed, and it turned out to be correct. And he probably didn’t understand why it worked, because he thought he would apply the same methods to higher dimensional magnets, and he promised that in his original paper. But of course, it turns out that what he’d locked on to, involves some very deep mathematics that took about 50 years to understand.

So, most of the scientists who work in magnetism, they knew of the existence of Bethe’s exact solution for a chain of magnetic atoms where the spin took the smallest possible value of 1/2, and locked superficially exactly like the spin wave theories that worked for, that were basically semiclassical, that worked in higher dimensions. And so, they assumed that ok, there was a little kind of, some kind of technical problem with the spin wave theory, but it had to be morally correct; the detail, this little problem didn’t really matter. But they were completely wrong, because the resemblance was purely superficial, and we now know that Bethe’s solution describes very interesting excitations which you call ‘spinons’ now, that it should carry spin-1/2 why the spin wave would carry spin-1, and they got nothing, it’s just an accidental coincidence of the formulas.

I actually, by covering this from a completely different angle, which was that there had been a, again going back to the 30ies, a remarkable relation between fermions and spins, a spin-1/2 object could take two possible states; up and down. And if I have an orbital which you can put a fermion in, it can either be empty or filled, and there is a kind of mapping between the two. But fermions, they have this fundamental property that if you exchange two of them you get a minus one sign, so fermions are said to … the operators that create them are said to anti-commute well. You get a minus sign if you add or remove them in different orders, while the spins don’t have that. But Jordan and Wigner in the 30ies had discovered a nice little way to map the two by putting in, what’s now called a string, in front of the things in the operator. So, they had a remarkable relation between spins and fermions that worked. So, it was pointed out that you could map the spin half chain problem that Bethe solved into a problem involving fermions. And at some limit these were non-interacting fermions, so you could understand the thing.

Based on that language, a completely different language, which I had followed on some work that Alan Luther and Vic Emery and I guess Luther and Ingo Peschel had done in the early 70ies. This allowed one to calculate things – not exactly – but in an approximate method. While the Bethe solution, the one that gave you the energy levels, no one at that point had ever worked out how to calculate anything else out of these very complicated wavefunctions that Bethe gets. It took another, probably 20 years, before, finally the solution of how to calculate with Bethe’s solution was found. So, using these methods, which a normal physicist, who isn’t a very abstract mathematician, could actually do a calculation. So, in this language of the fermions, I made a kind of theory called ‘Luttinger liquids’, which gave a general scheme for what interacting fermions should do in one dimension, and then applied it to this spin-1/2 model. So, Luther and Peschel had made a large progress in the spin-1/2 model; by treating it as a fermion field theory we could actually do a calculation.

But they had missed a detail, which was if the spins like to be in the line plane, like compass needles, you could treat it easily this way, because one of the limits is non-interacting fermions. But the interactions in the fermion picture when the spin is to stand vertically upwards and down, like point towards the North pole or South pole, and they’d missed out why the transition happens at a certain point. From doing numerical calculations, in fact, by applying my general theory to the Bethe “Ansatz” solutions, I saw within them exactly what had been missed. And so, it gave me the understanding of how to properly do a treatment of spins. And then I could actually treat any spin, not just spin-1/2, and immediately I did it. I found that in fact, using arguments based on what Kosterlitz and Thouless had done, that the conventional argument was just wrong. And something quite different happened for the next spin up, spin 1, and all spins which were integer values rather than half-integer values. So, that was it. In fact, this paper states the first lines of stating that, you know, this leads to a very unexpected conclusion; that the spin-1 chains behave completely different from what the Bethe “Ansatz” solution said/did, and it was nothing to do with the spin waves.

So, this was kind of against the orthodoxy … because a lot of people … I mean spin chains were kind of obscure, but in the 70ies a lot of people started working on them because there was some possibility of actually making materials that did this. And, in fact, spin chains had grown a lot of current research on understanding how thermal equilibration happens; people are using spin chains for all kind of things now. But, anyway, this started getting popular, but I was unable to get this published. I sent it to one journal, got turned down with three dismissive reports. So, I just sent it to another one, and I got essentially, I don’t know if it went to the same referees, but essentially, I got the same kind of reports back. So, it took another couple of years, to get the thing published, I mean I, perhaps I didn’t explain it in the language that these people could understand. But in fighting these referees’ reports, I rephrased the arguments in a much more, perhaps, a better way. But the original way I discovered this got completely lost from it. So, this paper was actually, was referred to in the literature because people went on and basically validated the results in here.

There wasn’t an archive at those times, and somehow, I, in moving around, I didn’t have this paper. The people who worked on this problem, and actually validated that I had found what they referred to, that they never had any copies anymore. The institute in Grenoble, the institute in Laue-Langevin, where I did this work, there was an official number of pre-print, but of course they had cleaned out all their cabinets. And I was searching in the boxes in my basement. In fact, the Swedish television people wanted me to meet to show them the boxes, because I have a problem with throwing out papers. So, I have lots of boxes, unopened boxes, which had accompanied me in various moves that was accumulated, and I thought that it might be in there. But in fact, a Hungarian physicist Jenő Sólyom, who worked this problem, eventually came up with the missing pre-print. So, it was actually very interesting cause it actually, it does make a connection that I had forgotten about completely with the work of Kosterlitz and Thouless.

Initially you wouldn’t even think there was a connection because their work was based on, essentially, classical problem of a super fluid film in two dimensions. And Kosterlitz, when he talks about this, he makes it clear that he just deals with classical mechanics, and quantum mechanics introduces too many complications. But, in fact there is a remarkable relation between two special dimensions and one space- and one time-dimension, which is kind of like the relation between relativity in space-time; three space dimensions and one time-, and you get the four-dimensional space-time continuum. Well, a one-dimensional system, where you have a one-dimensional space-time continuum, one plus one dimensional, you have time and space. And there is a remarkable mapping that maps statistic, classical, statistical mechanics of systems at finite temperature described by the Boltzmann factor, with probability weight, and quantum mechanics, which is described by an amplitude for a process to happen. So, the vortices in two dimensions, which if you wonder around the vortex, the spins rotate by two π, turns into, in one space-time dimension, what’s called an “instanton” process, or “tunnelling” process, where, if the spins are all kind of untwisted at one time, and they twist through one turn around a plane and a second plane, and if I do a walk in space time around that, the spin rotates by two π. But the remarkable thing is that quantum mechanics is far richer than the statistical mechanics, cause in the Boltzmann’s formulation of statistical mechanics, the weight factor, the probability factor is always positive. Probabilities, in classical mechanics, are positive, where in quantum mechanics, there are in general complex numbers. But if there is some kind of time-reversal-invariance property, they can be their real numbers, which are plus or minus. But, when things can be both plus or minus, when you combine them, they can cancel, which cannot happen in that.

So, it turned out that the basic process, which should be, the general process was the one I discovered, and the spin-1/2 was a very special case, which was behaving differently, so, the question was not why the spin-1s behave differently from the spin-1/2s, but why the spin-1/2s behaved the way they did. And that’s basically because there was a minus one factor when cancel things. So, this relation to Kosterlitz-Thouless was actually how I realised the thing is a mapping from the classical Kosterlitz-Thouless transition in two dimensions, to the quantum version, in one plus one, which has been incredibly fruitful for all the people working in one-dimensional systems too. So, despite Kosterlitz’s disembowel of quantum mechanics, in his work it has actually been very important also in quantum mechanics. So, this paper has that in it, and as to say, the published version, which is two years later, that connection was completely lost. So, it’s very interesting to remember this and how I discovered things. I was very pleased that someone finally, after I had drawn a blank everywhere, for copies of my own work …

Did you ever doubt yourself; did you think that you must have made a mistake or must be wrong?

Duncan Haldane: No, I was always confident. I mean people were kind of telling me things like this is a … some referee reports were saying this was obviously wrong and in complete contradiction to fundamental principles of physics, such as continuity, or something like that. About that time … and other people called this the ‘Haldane conjecture’, I never, actually I looked in the paper and I used the word ‘conjecture’ about some other tiny detail, which is not the main thing. Somehow this got built as, not a prediction or a theory, but a conjecture – as if it was a guess, a speculation. And of course, it wasn’t. But sometime around that time, the Bethe’s method was applied to a modified spin-1 chain. In fact, two authors in the Soviet Union seemed to have found this spin-1 chain solution about the same time. So, there was two versions of this, and I was the referee of both, actually. And I guess they, of course, found something that looked very much like the exact solution of the spin-1/2 chain. But it wasn’t solving the regular problem, there was a slightly modified problem; an extra piece was added on. And, I suppose I might have had about ten minutes worth of soul-searching when I got the first of these to referee.

But finally, I realised that they were doing a slightly modified problem that was special. And in fact, that turned out to be the case; that if you add this extra piece to the problem, and vary in strength; if you switch it to zero – nothing, it’s the same as what I predicted, but as you switch it up, there’s a critical point at which a phase transition to another kind of state, called the dimary state happens. The solvable, the models aren’t exactly solved by Bethe’s method; they’re usually special, and this one was exactly on a critical point. Now, it turned out that these models were extremely interesting for conformal field theories, which were turned out. So, lot of developments happened in this whole business. And those were very interesting models, but they weren’t generic case, so, I suppose I had ten minutes worth of doubt. But I quickly recovered. It was so clear to me that I couldn’t quite understand why people wouldn’t appreciate my arguments. But maybe we feel that we are clearer than we really are …

Is there any person that you have worked with that has been a huge inspiration for you?

Duncan Haldane: I was very fortunate to work with Philip Anderson, who was a 1977 Laureate in Physics, or one of the three. In fact, he got the Nobel Prize with his graduate advisor, Van Vleck. So, I guess that puts a big pressure on my students to make sure they don’t break the chain, right? So, he had a very unorthodox way of thinking, and maybe that rubbed off on me in some way. I mean, I was extremely inspired by the way he thought about things. I think obviously that was a big influence on the way I developed as a physicist that I had a good chance to interact with Philip Anderson, who has done an amazing amount of different things. With Philip, the Nobel Prize he got wasn’t for the thing he did which was the best; a bit like Einstein, who got the Nobel Prize for the photoelectric effect and not for the gravitational theories.

What do you feel, do you feel that you’ve gotten the prize for the thing you are most proud of?

Duncan Haldane: Well, I’m proud of a number of things. I guess I, this was interesting; it’s probably only in the magnetic chain stuff I always felt was ok, it was interesting, but it didn’t have any obvious applications. It was maybe changing what you thought about things, but more of a kind of theorist thing, right? But it was interesting to a special … some set of people. But a lot of people were very impressed by it. I suppose, partly because … if a lot of people had post it, they had to say, well, it was either, if it was obvious – it meant they were stupid. So, I had to be brilliant instead, to have discovered it, I suppose. But no, I’ve done a number of things, but, the general theme I think, has been this topological matter. And, the other piece of work I did, which was to find, to realise, that you could have a quantum Hall effect without a magnetic field, just due to some kind of magnetic interactions in the system. It is potentially a very practical, useful thing. But it has taken some time to actually be creative in real materials. You know, it doesn’t really matter to me what they gave it for I suppose. It’s kind of a great honour, and it is great for our field, actually.

What I think has happened is that, when I look back and see what, the way I was taught about physics, in the 70ies, and the way that condensed matter was feud by people. I think, my advisor Phil Anderson, were one of the few people who took a very different view point. But the way we think about it has just changed. The things that went in the textbooks, that people thought were important, they’re kind of just rather boring details. And all the new stuff is absolutely absent. So, it’s been a, you know, great honour I think to be involved in laying the groundwork for this complete change of the way we look at things. So, I suppose that’s probably why this prize has happened. And partly because of what happened about ten years ago; some of this work was generalised to so called “time-reversal-invariant topological insulators”. It suddenly turned out that there were real topological materials that had been sitting on people’s shelves for many years without being noticed. And, just the power of theoretical ideas to, reveal something, very worthy, big calculators and experimentalism that’s just not noticed, it’s amazing, right?

So, it’s a question of really, I think we need the imagination to see what quantum mechanics can do, and we need to understand all about quantum mechanics, it’s laws, but we don’t really understand this potential. In the past things were studied by basically hitting them with a hammer, but now we have arrived at where we are actually able to try and tweak or nudging things around, and understand how quantum mechanics influences what happens. And I think my basic line on this, is that quantum mechanics does stuff much cooler than we could’ve even imagined, and part of this emerges, part of this work. And much more, cooler, things have been emerging since then. And people have dreams of quantum computers and all kinds of quantum information technologies and things. And I am not sure what’s going to happen, but something’s going to happen, because so many people now are looking at this, and it has really become … I mean, once you’ve got real things, then people start taking it seriously. And it has become incredibly inspirational and exciting to lots of young people. And everywhere one sees, an experimentalist gives a talk and he views a little video of a coffee cup turning into a doughnut and backwards, a physicist, and you can find this on YouTube and …

The idea that topology has something to do with this material – it just, makes such a big impact on people. It’s just incredible how this thing has taken off. So, these ideas were kind of a sleeper for a long time, and it’s really the final thing where you’ve taken – it’s got three mathematical backgrounds to it, which, you know, I don’t really understand. But, I understand some of it, but just knowing the abstract mathematics doesn’t lead to something either. The mathematics was actually around for a very long time, since the 40ies, and it was only when some mathematician realised, the mathematical physicist realised, that, the formulas for example that David Thouless, and Kohmoto, Nightingale and den Nijs had found, were actually, they found that this topological, this number that didn’t change, and it was recognised, oh this is Chern’s integral of a curvature of a manifold, right?

Once you kind of name the mathematics, then of course there’s lots of tools around. But to actually find it, you’ll have actually be able to do, a concrete little, what they call a toy model calculation. So, the mathematics is often too abstract to actually pin down. But in what I have done, and what Thouless did, is to be able to do very simple calculations, that you can actually do, preverbally on the back on an envelope. Perhaps you’ll need a computer a little bit to do something simple. But to actually see what a model does you need to strip all the irrelevant details out of something and go down to the simplest, possible model, that contains the physics that you’re interested in, right. And I take this line in seminars that it is almost like contract law. Because if you have a contract, very often it’s got a little phrase in it that says that “anything that’s not written in this contract cannot be considered to be part of it” and the contract is the entire document, right? Once you’ve got your model down to be very simple, and it still exhibits the physics you are after, then it’s not omissible to discuss, to attempt to use anything if you have already thrown away as part of the explanation of the thing. So, this is a technique to getting down to the cleanest, simplest example of things. Then, if you can actually do a calculation, then you can be concrete. And then maybe you can see how it works with the deep and beautiful mathematics that gets exhibited in the actual solution.

But the final thing you need, on top of that, is once you have actually shown it can be made in a model, in a toy model, it’s remarkable that the material science has got to the point where, if you think it can be made, someone’s going to make it. Before the toy models were attempts to make, you know, text-book thing for modelling complicated real matter, and the large school of ab initio calculation, to get everything right, all the details right. And of course, the people who worked on that, often had a poor opinion of toy models. But it turns out they missed all these fundamentally, simple and beautiful things. So, toy models are great, but once someone actually makes it, then you got the three ingredients; you got the mathematics, calculation that a kind of ‘simple working physicist’ can understand, and then, an actual material. Once that started to happen about in the last decade, once these three things came together, this field has just taken off, and who knows where it’s going to go.

It’s really obvious, talking to you, that you find this really engaging, and that you still find this immensely interesting. How have you been able to keep your enthusiasm up within this field during your career?

Duncan Haldane: I think we’ve just kept on, things just got cooler. I think in this whole field, I mean, it’s been so fruitful. It’s been actually great for young people at every stage in their career in this field. Other fields, like high-temperature superconductivity has really been the graveyard of many people, because it has been unclear, it’s complicated, and there’s lots of rival theories which fights this and that, and there’s people knifing each other… But in this field, every time a problem came up it got solved and something very interesting and new came up, and people said “fine”. But it’s renewed, it has kept on; new things have kept coming on, and in fact, it’s just been a sequence of progressively more and more cool things coming out. So definitely it keeps one’s interest up. And of course, you try and understand the big picture; the big picture is kind of gradually being assembled. So, it is still an exciting field and it is still going to continue to be an exciting field.

Thank you so much

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Press release

English

English (pdf)

4 October 2016

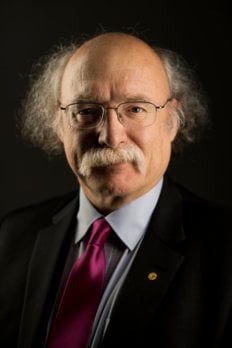

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Nobel Prize in Physics 2016 with one half to

David J. Thouless

University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

and the other half to

F. Duncan M. Haldane

Princeton University, NJ, USA

and

J. Michael Kosterlitz

Brown University, Providence, RI, USA

”for theoretical discoveries of topological phase transitions and topological phases of matter”

They revealed the secrets of exotic matter

This year’s Laureates opened the door on an unknown world where matter can assume strange states. They have used advanced mathematical methods to study unusual phases, or states, of matter, such as superconductors, superfluids or thin magnetic films. Thanks to their pioneering work, the hunt is now on for new and exotic phases of matter. Many people are hopeful of future applications in both materials science and electronics.

The three Laureates’ use of topological concepts in physics was decisive for their discoveries. Topology is a branch of mathematics that describes properties that only change step-wise. Using topology as a tool, they were able to astound the experts. In the early 1970s, Michael Kosterlitz and David Thouless overturned the then current theory that superconductivity or suprafluidity could not occur in thin layers. They demonstrated that superconductivity could occur at low temperatures and also explained the mechanism, phase transition, that makes superconductivity disappear at higher temperatures.

In the 1980s, Thouless was able to explain a previous experiment with very thin electrically conducting layers in which conductance was precisely measured as integer steps. He showed that these integers were topological in their nature. At around the same time, Duncan Haldane discovered how topological concepts can be used to understand the properties of chains of small magnets found in some materials.

We now know of many topological phases, not only in thin layers and threads, but also in ordinary three-dimensional materials. Over the last decade, this area has boosted frontline research in condensed matter physics, not least because of the hope that topological materials could be used in new generations of electronics and superconductors, or in future quantum computers. Current research is revealing the secrets of matter in the exotic worlds discovered by this year’s Nobel Laureates.

Read more about this year’s prize

Popular Science Background

Pdf 424 kB

Scientific Background

Pdf 800 kB

Image – Phases of matter (pdf 900 kB)

Image – Phase transition (pdf 622 kB)

All illustrations: Copyright © Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

David J. Thouless, born 1934 in Bearsden, UK. Ph.D. 1958 from Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. Emeritus Professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

https://sharepoint.washington.edu/phys/people/Pages/view-person.aspx?pid=85

F. Duncan M. Haldane, born 1951 in London, UK. Ph.D. 1978 from Cambridge University, UK. Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics at Princeton University, NJ, USA.

https://www.princeton.edu/physics/people/display_person.xml?netid=haldane&display=faculty

J. Michael Kosterlitz, born 1942 in Aberdeen, UK. Ph.D. 1969 from Oxford University, UK. Harrison E. Farnsworth Professor of Physics at Brown University, Providence, RI, USA.

https://vivo.brown.edu/display/jkosterl

Prize amount: 8 million Swedish krona, with one half to David Thouless and the other half to be shared between Duncan Haldane and Michael Kosterlitz.

Further information: http://kva.se and http://nobelprize.org

Press contact: Jessica Balksjö Nannini, Press Officer, phone +46 8 673 95 44, +46 70 673 96 50, [email protected]

Experts: Thors Hans Hansson, phone +46 8 553 787 37, [email protected], and David Haviland, [email protected], members of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, founded in 1739, is an independent organisation whose overall objective is to promote the sciences and strengthen their influence in society. The Academy takes special responsibility for the natural sciences and mathematics, but endeavours to promote the exchange of ideas between various disciplines.

Nobel Prize® is a registered trademark of the Nobel Foundation.

J. Michael Kosterlitz – Biographical

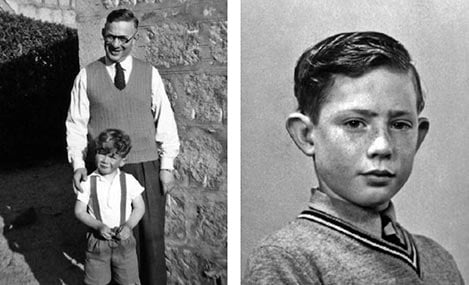

Childhood

Childhood

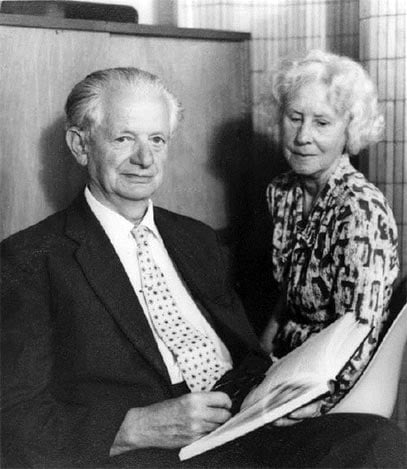

I was born on June 22, 1943 in wartime Aberdeen, Scotland and lived there for the first sixteen years of my life. My parents, Hans Walter and Johanna Maria Kosterlitz (Gresshöner) had fled Hitler’s Germany in 1934 because my father, a non-practicing Jew, came from a Jewish family and was forbidden to marry a non-Jewish woman like my mother or to be paid as a medical doctor in Berlin. Under the circumstances, my father decided that it would be in his best interests to leave Germany and accept the offer of a lectureship at Aberdeen University. My mother, who came from a conventional Christian German family, decided that she would follow my father to Britain so that they could be married, which they were in Glasgow.

I had a happy childhood in Cults which used to be a small village just outside Aberdeen and separated by farms and fields from the city but now is just another suburb of a much larger city. I was raised as a British child unaware of my German origins, although I was aware that my parents were different from those of my friends because they had a secret language used to communicate when they wanted to exclude me. My parents would have nothing to do with Germany and spoke only English at home except occasionally under special circumstances. As a result, I grew up speaking only English and had to wait several years before learning some basic German at school. In fact, for several years I did not know I was actually of German Jewish origin nor did I know what being Jewish meant. The only thing I knew was that a boy in my class got some extra vacation because of his Jewish religion. When this became known among the class, everyone wanted to change their religion for the extra holidays. My father had no interest in religion and left all instruction in these matters to my mother, who was a devout Christian. I was a nominal church going Christian until I left home for Cambridge University on a scholarship when, to my great relief, I could drop all religion and become my natural atheist self.

Education

My early schooling was in Aberdeen at a semi private school, Robert Gordon’s College, which I attended from kindergarten up to age sixteen. There I had a broad education including the sciences, mathematics, history, geography, Latin and French with a strong Aberdonian accent. Some of the teaching left much to be desired particularly in physics where even I, at the age of fourteen, could tell that the teacher did not understand the subject. My parents decided that I showed some talent for academics and that I was worth grooming for Cambridge or Oxford University. In 1959, I went to Edinburgh Academy where the English A and S level subjects were taught. There I was able to specialize in the sciences and mathematics. With the improved teaching, I found I could do best in physics and mathematics. Eventually, I concluded that the reason for this was that my ability to make logical deductions compensated for my unreliable memory.

At school, I was fairly average at the humanities but excelled at mathematics and the sciences. Chemistry was the science I enjoyed most because we were allowed a lot of freedom in the laboratory at school, where I would carry out various forbidden syntheses of explosives and other noxious substances. I remember a few occasions where the lab had to be evacuated when one of these experiments went wrong and a noxious gas escaped. Despite the enjoyment these chemistry “experiments” gave me, I was not very good at the subject because of the memory required and I had to make too many guesses, especially when we studied organic chemistry where the chemical formulae were too complicated to memorize. However, despite the rather boring experimental part, physics was where I excelled at school. It satisfied my six fact memory limit because I was able to deduce correct results more often than not. Also, about this time in my life, I discovered that I am red green blind and that this disability does not fit well with chemistry. Some of the experiments required me to distinguish between several test tubes each containing a different reddish fluid. They all looked the same to me, but my classmates assured me that they were all quite different. At this point, I decided that chemistry was not for me despite all the fun I had mixing the various chemicals I could access.

While I was at Edinburgh Academy, along with several fellow students, I sat the Cambridge University scholarship examination and, to my great pleasure, I was awarded a major scholarship in the Natural Sciences to Gonville and Caius College. A condition for attending Edinburgh Academy was that one joined the army cadet corps. Once every week in Edinburgh, I wore my kilt feeling foolish. Despite being born and raised in Aberdeen, Scotland, I did not have a drop of Scottish blood in me and had never worn the kilt before. I came to understand Edinburgh’s reputation as a windy city by parading through the streets in winter in my kilt in the usual cold horizontal rain which is an experience never to be forgotten.

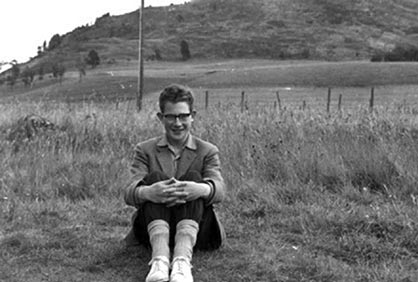

Undergraduate Years

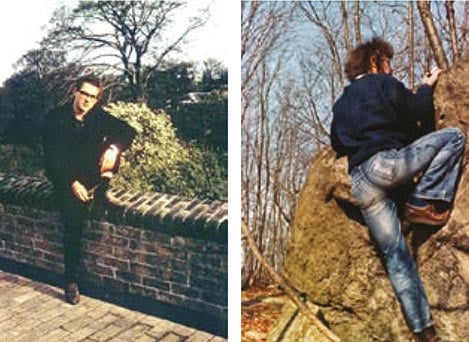

As an undergraduate at Cambridge from 1961 to 1965, I did the natural sciences tripos which covered most of the science subjects of that time. I chose to do physics, mathematics, chemistry and biochemistry because I enjoyed the chemistry at school. My color blindness again made this very frustrating and my poor memory made organic chemistry a bit of a nightmare as there were many situations where guessing did not work. I remember one situation in a biochemical experiment, where I ended up with a test tube containing some nondescript fluid. I was staring at it wondering what I should see in it or if I should do something else to the contents when, suddenly, it started to change color. Instinctively, I averted my gaze just before the test tube exploded. To this day, I have no idea what happened but that episode confirmed that chemistry was not for me and that the less dangerous and less memory intensive subject of physics would be my best bet. For fun, I joined the Cambridge Climbing Club which ran a bus or minibus to Derbyshire or North Wales every weekend. I discovered I was good at rock climbing and enjoyed the thrill of being high on a cliff with almost nothing to stop a fatal fall. From that moment, climbing at weekends became like a drug and I became obsessed by the sport.

About this time my grandmother died at age ninety-two and left me a small bequest which I promptly spent on a car and the necessary insurance. With the help of my little car a typical weekend would be scheduled as: Friday evening – drive as fast as possible to Llanberis pass in North Wales or to the Lake District or, in the cold winter, to Glencoe or Ben Nevis in Scotland for the ice climbing. Climb on Saturday and Sunday, if not raining, and drive back to Cambridge late Sunday night and early Monday morning. Then I would sleep until I woke too late to go to class, thus not having any lecture notes. The weekly tutorials kept my nose to the grindstone and rescued my academic career.

My life settled into a routine which was close to my father’s dictum of work hard and play hard. By now Berit had become part of my weekly routine. Although she did not climb herself, she enjoyed being with me in the mountains. On Friday evening, Berit and I would jump into the car and drive as fast as possible to North Wales and Berit blames this period in our lives for causing whiplash injuries to her neck. We would return to Cambridge or Oxford late on Sunday after a hair raising race through the dark and I would try to stay awake in class until the following Friday. I would often leave for an afternoon’s climbing on some closer rocks once a week or perhaps do a bit of climbing on some nearby buildings. I had so much fun with these extra curricular activities that I seriously neglected my studies, especially in my final year. Also, in the Part 1 exams at the end of my second year at Cambridge, I did rather well in line with the expectations of me as major scholarship holder and I now expected to obtain a first-class degree in my third year with ease.

However, I did not perform as expected in the all-important final year and ended with an upper second class degree. I am a bit surprised that I did so well because I hardly studied, nor did I attend many classes mostly because I had done so well in the first two years without studying much. I thought to myself “Michael, you are some sort of genius”, but the final year taught me differently. Shortly before the final exam, I realized that I did not know what had been in the syllabus and panicked. I borrowed lecture notes from friends as I did not have any and read and read for most of each day as I watched time passing inexorably towards the final examinations. I struggled with questions I half understood, knowing that my enjoyable undergraduate days of climbing and pubs were now exacting their price. In the summer, I went on a climbing expedition to the Peruvian Andes where I could forget my Cambridge failures.

While I was in Peru, my father arranged for me to have an extra year, 1965– 66, at Cambridge to do Part III mathematics to try to improve my disappointing performance. He was an eminent academic who well understood the importance of a Ph.D. degree. This year was a mixed success because I did not appreciate the almost rigorous approach of the applied mathematicians and physicists teaching the courses. Much of what I learned I found useful later. Unfortunately, I had not learned my lesson and my obsession with rock climbing again prevented me from spending the necessary time and effort my studies really needed. Again, I had to be satisfied with an upper second class performance. At the end of the year, I was lucky to have the necessary qualification for graduate school at Cambridge, but not in high energy theory which I was determined to do. I was offered a position with Nevill Mott in experimental solid state physics but I turned this down in favor of an offer from Oxford in high energy theory.

Graduate and postdoctoral years

I spent the next three years, 1966–69, in Oxford sharing a rented house with several medical students and my future wife, who spent the time complaining that she had to work too hard keeping several messy males tidy, clean and fed while I worked on my Oxford D.Phil. We quickly fell into a routine where Berit left for work at 8:00 am and I at 10:30 am to arrive for the 11:00 am coffee at Rudolph Peierls’ department of theoretical physics. My D.Phil. supervisor, John Taylor, left me alone to do my own research and find my own problems which upset me at the time but, in retrospect, this was excellent training for my later career. Whatever his reasons, I am eternally grateful to John for putting up with my foibles at Oxford. I managed to write three papers on Regge poles and the Veneziano model, a precursor to modern string theory, with other graduate students.

These were the subjects I would continue to work on in Torino and later at Birmingham until I changed fields. In 1969, I managed to write my thesis, imaginatively titled “Problems in strong interaction physics”, which, I suspect, has never been read. Of course, the weekends and vacations were still reserved for my climbing obsession, which still occupied all my leisure time. At this time, I spent all summer vacations climbing in the French or Italian Alps and even Yosemite Valley in the USA and managed to get quite a reputation as a mountaineer.

Our next adventure was when I managed to obtain a Royal Society grant for a postdoctoral fellowship which I could use anywhere in Europe. I decided on the Istituto di Fisica Teorica, Torino, Italy because Sergio Fubini, one of the pioneers of modern string theory, was there but, more importantly, it was close to the Alps where the best mountains such as Mont Blanc are situated. Neither Berit nor I spoke any Italian but we were young enough that this was just a minor challenge to be overcome. We had many other interesting challenges to overcome of which renting an apartment and furnishing it, all in Italian, was one. Another was to deal with the local car drivers. I learned to love alpine skiing, made contact with outstanding local climbers and created a climb in the Val d’Orco which bears my name, “Fessura Kosterlitz” which was not repeated for a decade. My achievements in physics are somewhat less well known but I did do some very long calculations on a precursor to modern string theory. This resulted in one paper “The General N-Point Vertex in a Dual Model” with a fellow postdoc, Dennis Wray. I did not realize at the time that I was in the forefront doing research in what was later to become string theory.

While I was in Italy, there occurred a pivotal event which led to my Nobel Prize. I applied to CERN for a postdoctoral position for 1971–1972 but failed to submit the necessary paperwork in a timely fashion and was turned down. Panic set in as the prospect of unemployment hung over me. Berit walked to the main train station to buy a British newspaper which contained advertisements for academic jobs. There was one for a three-year postdoctoral position at Birmingham University in England and I dutifully applied for this although I did not really want to go there for high energy physics. I got offered the job and duly accepted.

Another, even more pivotal, event occurred in Italy. Berit and I had by now been an inseparable couple for seven years. The question of marriage arose on and off during those years, but we decided that I was too immature and the three-year difference between our ages was too great. By now we felt differently and I suggested that our relationship seemed very stable and we might as well make it legal. We married in Torino in September 1970 after a long battle with the local bureaucracy. Also, this avoided the problem of obtaining work permits for Berit. Since then, we have had more than a few adventures and three children who are now settled in Boston and Providence in New England. We have also been blessed with five grandchildren.

I spent the next three years, 1970–1973, as a Research Fellow at the Department of Mathematical Physics at Birmingham University. I continued my calculations on the dual resonance model of Veneziano and was about to write up my calculations when a preprint by a group at Berkeley doing exactly what I had done appeared on my desk. Needless to say, I was rather annoyed but shrugged my shoulders and started a new long and laborious calculation. I completed this and started to write it up when another Berkeley preprint arrived on my desk. When this happened yet a third time, I did get rather upset and went from office to office asking the occupants if they had a problem I could look at or if I could help in some way. Eventually, I found myself in David Thouless’ office listening as he described concepts and ideas I knew nothing about. He talked about superfluidity in 4He films, crystals in two dimensions, vortices, dislocations, topology and many other related ideas.

Although this was all new to me, as was statistical mechanics which I had ignored as being unnecessary for high energy physics, the ideas made sense to me. After I left David’s office with my head spinning with all these new ideas and concepts, I returned to my own smaller office and began to work on these new wonderful ideas which David had introduced to me. The central idea was that the only way a flow in 4He can dissipate is by the creation of vortices and their subsequent motion. A superfluid can be characterized by the absence of free vortices and a normal, dissipating fluid by the presence of a finite concentration in thermal equilibrium. In two dimensions, the problem becomes equivalent to the equilibrium statistical mechanics of a set of point charges interacting by a Coulomb potential. David and I introduced the concept of a vortex as a topological excitation or defect. The same ideas can be used to discuss the melting of a two-dimensional crystal with point dislocations playing the same role as vortices in a superfluid. David and I wrote two papers on this [1, 2] where we discussed the basic theory of defect mediated transitions. About this time, David casually directed my attention to some papers by Phil Anderson and coworkers on the Kondo problem and its mapping to a one dimensional 1/r2 Ising model [3] which introduced me to renormalization group methods, although this terminology only came into use later. I did nothing for six months but reading and re-reading this seminal paper and reproducing the calculations to try to understand it. During this time, Berit tried in vain to tidy my office but was firmly told to leave all papers alone. A year later, based on this research, I published a paper which discusses a renormalization group treatment of the two-dimensional planar rotor model of superfluid 4He [4] which is the basis for the exact prediction for the superfluid density [5].

My next position arranged by David Thouless was as a Postdoctoral Fellow at LASSP at Cornell in 1973–74. There I met Michael Fisher and his young, very smart graduate student, David Nelson. Even at this early stage in his career, David demonstrated that he was going to become something special. I was excited by the prospect of learning about phase transitions and critical phenomena from the Cornell experts, Michael Fisher and Ken Wilson. Field theoretic methods and the epsilon expansion of Wilson and Fisher [6] had permitted enormous progress in understanding a huge variety of phase transitions and I badly wanted to be one of the pioneers in this. Working with Nelson and Fisher opened my eyes to what physics is all about, how important experimental data are and how to choose the problems to work on. In the 1970s, critical phenomena was a field which was at last opening out by Wilson and Fisher’s epsilon expansion methods. With Nelson and Fisher, I worked on bicritical points using renormalization group methods. To our great pleasure, we were able to understand in great detail the shape of the phase diagram in the vicinity of a bicritical point and why the various phase boundaries had the shape of experiments on anisotropic antiferromagnets. This was at the height of the development of critical phenomena in 4 − Ɛ dimensions and I was excited to be in the middle of it with the leading authorities in the field. I learned the importance of testing one’s theory against the ultimate authority in physics, experiment.

During all my postdoctoral years I kept to my mantra: first climbing, then physics and last family. In fact, when I was in my twenties, I was one of the best climbers in Britain and even considered giving up physics in favor of a professional climbing career. My teaching duties prevented me from going on any of the Himalayan expeditions I could have joined. However, on thinking about the possible consequences of this choice, sanity and my wife finally prevailed. I realized that, although I was technically good enough, a career in academia and physics would allow me enough vacation time to indulge in my climbing obsession. Some of my climbing acquaintances had chosen to become professional mountaineers and a few succeeded but most did not. I decided that I would probably not succeed in this.

Tenured years: Birmingham and Brown

I returned to Birmingham University in 1974 as a tenured lecturer, then was promoted to Senior Lecturer in 1978 and finally to Reader in 1980. I continued working on phase transitions and critical phenomena while teaching two courses at the same time. David Nelson and I managed to produce our important prediction for the superfluid density of a thin film of 4He [5], but my significant output slowed down although I produced several papers on critical phenomena. David Thouless was still at Birmingham, during which time we continued our collaboration on spin glasses until he moved to the USA. I spent a semester in 1978 as a visiting professor at Princeton, Bell Laboratories and Harvard respectively, bringing my family. My stay at Harvard was especially productive as David Nelson and I wrote our paper “Universal Jump in the Superfluid Density of Two-Dimensional Superfluids.”

By 1978 we had two children in Birmingham schools and my wife and I were happy and thought we were settled there forever. I was doing what I loved, climbing, immersed in physics, and spending the remaining time with my growing family. However, this contented period of my life was not to last, because I contracted the nasty autoimmune disease of multiple sclerosis. I awoke one day in September 1978 and was unable to stand up because my balance did not function. I was admitted to hospital where I spent one week while the doctors tried to figure out what was wrong. Eventually, a solemn neurologist said that there were two possibilities, a brain tumor or multiple sclerosis, of which the latter was the better alternative. It turned out I did indeed suffer from MS and life as I knew it was forever changed. Needless to say, I did not react well to this news as I assumed it meant the mountaineering half of my life was over and I would have to live the rest of my life without it. My wife was not as upset as I was because, by this time, a number of my climbing friends had died in climbing accidents and she was relieved that this would not happen to her husband. However, this thought was little consolation to me who could not envisage life without the mountains and I went into a deep depression which lasted for several years. The professor of neurology offered these kind words of encouragement, “There is no cure, some people live longer than others. If you can look back after 25 years you will know how bad a case you are.” Needless to say, this information also affected my physics productivity for a few years.

In 1979 I was offered a position as a tenured full professor at Brown University and Birmingham counter offered a promotion to a research professor as an incentive to stay. This would be at a Center of Excellence centered at Birmingham, which I was inclined to accept. I was about to refuse the offer from Brown when Birmingham abruptly withdrew their offer. Combined with my illness, for which I subconsciously blamed Britain, this was the last straw and I immediately tendered my resignation and left for Brown, where we have been since 1982. My wife and I finally became citizens of the USA in 2004 because, in that year, Sweden permitted dual nationality and my wife did not wish to give up her Swedish nationality. As a British citizen, I had no difficulty because Britain has always permitted dual nationality. After 9/11, I felt that my wife and I and, especially, our children needed the protection of citizenship, so we paid a lot of money to an immigration lawyer and became US citizens in 2004.

At Brown, my interests changed somewhat and, with the help of a grant from NSF, I started to work on various effects in two dimensional arrays of Josephson junctions such as disorder and in a magnetic field. These can be represented by a frustrated planar rotor model, which is quite different from the original 2D planar rotor model [4]. In this, I was greatly helped by a very good graduate student from Brazil, Enzo Granato. This system is an excellent system for the study of many variants of the original system of Kosterlitz and Thouless and is still under quite active theoretical and experimental investigation. We looked at some of the more elementary aspects of the system and slightly increased our understanding of it. These experimentally accessible variants of the model took us out of the realm of analytic work and my student and I turned to numerical simulations, which was the only way we could make any progress. This has turned into a more than twenty-year collaboration with Enzo at INPE in Brazil.

In 1985, I went on a sabbatical to France, bringing my family as I realized this might be the last opportunity for a family adventure. The children went to French schools and I spent six months at Saclay and Orsay with my Brown graduate students continuing the work on planar rotor models.

On return to Brown I became interested in numerical work with a couple of graduate students from Korea. Our projects were to study the kinetics of growth of a surface by random deposition. We studied the scaling of the interface width with time and evaluated the exponent to a high degree of accuracy. However, we could not compete with the massive simulations from a group in Germany. The other project was to investigate if it was possible to identify a weak first order transition by purely numerical methods [7] which method is still being used in 2016. Jooyoung has turned his talents to the protein folding problem and his group is now recognized as a leader in this field as they consistently score very highly in the CASP competitions. A Japanese graduate student, Nobuhiko Akino, has been very successful in his numerical work on randomness in superconductors and in XY spin glasses which have been longstanding intractable problems. We concluded that an XY spin glass exists in three dimensions and above, which result can also be obtained via massive simulations.

For reasons which are still unclear to me, I lost my NSF funding over this and have never been able to get it back. However, the problem never stopped to intrigue me and over the last ten years I have doggedly pursued the solution although it has proven to be somewhat elusive. I had a brilliant graduate student given to me by Brown who was invaluable help to me doing difficult numerical work, and together we managed to get a paper accepted in 2010.

I also have had a longstanding collaboration for the last twenty-five years with my colleague Tapio Ala-Nissila in Finland working on phase field models of growth. This is a surprisingly successful method for the numerical study of growth in fluids and in solids which we recently applied to the hydrodynamics of crystals [8]. This collaboration has also included my colleague, Martin Grant, at McGill in Montreal, Canada and Ken Elder at Oakland University in Michigan, USA as well as my Brown colleague See-Chen Jing. I also started a collaboration at the Korea Institute of Advanced Study in Seoul, Korea where I am now a Distinguished Professor visiting for two months every summer. Even at my advanced age of 73, physics still fascinates me because there are so many problems waiting for a solution that, despite my increasing incompetence, I would like to see understood before I retire. Perhaps in this respect, I am like my father who refused to give up working until he was over 90! On reflection having produced nearly sixty papers in my time at Brown is not bad, but nothing will ever compare to the exhilaration of our 1977 paper [5] when theory agreed quantitatively with experiment [9]. Each summer, Berit and I travel a lot, spending time in Brazil, Finland and Korea but always keep four or more weeks sacrosanct for our Swedish summer house where we can relax completely by watching the grass grow. The only disadvantage is that it always does grow and then needs cutting, which gives me about the only exercise I have during the year.

Last but by no means least, I am happy that I have managed to work since that dreadful day in September 1978 when I was diagnosed with MS. The twenty-five years have gone and, as predicted by the neurologist then, I now know the outcome. I was not a bad case. I had attacks every 18 months from age 35 to 55, some quite bad, some small relapses. When I was 55 my neurologist put me into a trial for a new MS drug. This was very successful and opened up a whole new field of pharmacological drugs for the easing of MS. Since then, I have been lucky in that I have never had another attack. I only battle the deadly fatigue that comes with the disease. I want to take this space to tell any budding scientist that, however bleak the future may seem due to illness or other problems, one cannot say you will not be successful.

More people than I can list here have contributed in vital ways to my success. Those that are probably the most important are David Thouless whose friendship, patience and collaboration are central to my career, Berit, my wife, for her patience and forbearance with my peculiarities and absences when I was either climbing mountains or working too hard and my children, Karin, Jonathan and Elisabeth for putting up with and loving their strange father who was absent too often and too long. I also acknowledge the support and friendship of my colleagues at Birmingham and Brown.

References

- J.M. Kosterlitz and D.J. Thouless, J Phys C: Solid State Phys 5 L124–6 (1972).

- J.M. Kosterlitz and D.J. Thouless, J Phys C: Solid State Phys 6 1181–203 (1973).

- P.W. Anderson, G. Yuval and D.R. Hammann, Phys Rev B 1 4464 (1970).

- J.M. Kosterlitz, J Phys C: Solid State Phys 7 1046–60 (1974).

- D.R. Nelson and J.M. Kosterlitz, Phys Rev Lett 39 1201 (1977).

- K.G. Wilson and M.E. Fisher, Phys Rev Lett 28 240–3 (1972).

- Jooyoung Lee and J.M. Kosterlitz, Phys Rev Lett 1990 137 (1990).

- V. Heinonen et al., Phys Rev Lett 116 024303 (2016).

- D.J. Bishop and J.D. Reppy, Phys Rev Lett 40 1727–30 (1978).

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

F. Duncan M. Haldane – Biographical

I was born in London in 1951, in a medical family who greatly valued science and education in general, but never tried to push their children to go into medicine, although my younger brother did choose that path. My father was a psychiatrist working in the newly-created National Health Service, and came from Scotland. He had wanted to become a psychoanalyst, but the war had prevented his planned training under Freud’s pupil Melanie Klein, and he was trying to find some way to apply techniques or insights inspired by psychoanalytic theory to the much more limited possibilities for psychotherapy in an NHS practice. My mother was a Carinthian Slovene from a bilingual region in southern Austria, who had met my father when he was an army doctor in the British Occupation Forces there. She was a medical student working in a hospital when she met him, but never managed to complete her studies after coming to Britain, because all the exams she had passed in wartime Vienna would not have been recognized, and she would have had to restart all the medical training from scratch, in what was, to her, a foreign language. Instead, she had a family. My parents’ backgrounds gave me a multicultural heritage, with relatives in both Scotland and in Austria, where we often visited for summer holidays, so I became reasonably fluent in German, but sadly my command of Slovenian remained very basic indeed. My mother was proud of her heritage, as was my father of his, and he would wear a kilt on formal occasions, so although I grew up in London, without a trace of a Scottish accent, I self-identified as half-Scot, half-Slovenian.

I was sent to private schools, first a mixed elementary school a short walk from our house in Bedford Park, in west London, where I appear to have excelled in subjects like arithmetic and spelling, but always lost out on my handwriting skills, which remained messy and irregular, despite my being made to copy out pages of text again and again (or so it seems in my memory). When I was ten, I was sent to the “preparatory school” (Colet Court) for St. Pauls School, and then to St. Pauls itself, which is a well-known “public” (i.e., private) boy’s school noted for a rigorous educational curriculum. The school was very cosmopolitan, and was mainly a day-school with pupils coming from many parts of London, with a small boarding component. I was one of the one hundred and fifty-three scholars at the school (the number has biblical significance as the number of fish miraculously caught by the apostles), and because of this, I wore a little silver badge in the shape of a fish.

I always remember being interested in mathematics and science. In English schools, at least at that time, one had to specialize early. Looking at the list of General Certificate of Education “O levels” that I took, they were English, Latin, French, mathematics, “physics-with-chemistry,” with the only unusual one being “physical geography and elementary geology.” At some point I had to choose between continuing with history or geography, and the rocks and minerals seemed interesting and I was fascinated by the crystal collection the school had (perhaps an early attraction to “condensed matter”?).

For “A” levels, I just have mathematics, physics, chemistry, so somehow, I never studied biology (I think one only studied it if one was planning to go to medical school?). Of course, as these last years of school were during the late sixties, there were lots of distractions for teenagers in London during that period, but I managed to keep my academics on track. In my final year at school, I had a very enthusiastic and inspiring physics teacher who got me interested in the subject, while previously I had found chemistry definitely more interesting.

Somehow, I managed to combine interest in science with interests in rock music and sixties counterculture. I had a gap of nine months after leaving school, and before starting University, and decided to travel. I worked for a while at a book publishers’ organization extracting data on names and fields of study of faculty members from German university catalogs, and with my savings, and a large backpack, then set off on the then-well-traveled overland trail to India and Nepal via Iran and Afghanistan (and back!) – a journey impossible today! (I would later get to see India (and Nepal) from a rather different perspective during visits as a professional Physicist.)

I was admitted to “read” Natural Sciences at Christ’s College, Cambridge where I “matriculated” in October 1970. Three subjects plus mathematics were required, so I finally had the chance to learn some cell biology as well as physics and chemistry, but I found I was not so gifted in the laboratory, and after an experience when I accidentally swallowed some nasty chemical I was supposed to measure out a small dose of using a “mouth pipette” (I do not believe such things still exist with today’s work-safety rules) I decided I should opt for prudence and focus on theory!

In my third and last Cambridge undergraduate year, 1973, I took a class called something like “advanced quantum mechanics” taught by Phil Anderson, where, if I remember correctly, he talked about the problem of localization by disorder, the Kondo effect, and other inspiring things. These were deeply conceptual quantum problems different from the diet of scattering problems which seemed like mathematical exercises in partial wave expansions and spherical harmonics that the more conventional classes had been feeding us. I was hooked and decided that if I was accepted to stay on at Cambridge as a graduate student in the Cavendish Laboratory (which happened), I would like to work with Anderson. I also considered working with Michael Green on an intriguing problem of “massless spinning relativistic strings”: since string theory as a model for the hadrons was abandoned shortly thereafter, and took ten years “in the wilderness” till it was repopularized as a possible theory of quantum gravity, my choice to work with Phil seems a fortunate one, at least for one made in 1973! It is probably the case that any successful research career can be traced to “accidentally” making a series of non-obvious choices at the right time, and various chance events. I think it was the concreteness of condensed matter, in that it was much easier to experimentally realize systems that exhibit all sorts of remarkable effects, that kept me on the condensed matter theory trail. In some sense, particle theorists have only one physical vacuum, with its beautiful but highly constrained Lorentz point-symmetry group, to play with, while condensed matter physics can “build” a huge variety of model vacua with different symmetry groups and “elementary particles” (elementary excitations), and play with them experimentally.