Nobel Prize lesson

Explore the free, readily available lesson on the economic sciences prize 2025 including videos, slideshows and more.

©Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Your Majesties,

Your Royal Highnesses,

Excellences,

Dear Laureates,

Ladies and gentlemen,

On behalf of Professors Shimon Sakaguchi and Fred Ramsdell, I would like to thank the Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institute and the Nobel Foundation.

On October 6, while I was desperately trying to sleep through the 1:00am scam calls from Sweden, and Fred, high in the backcountry of Wyoming, was blissfully unaware of the worldwide excitement that was brewing, Shimon had the good sense to live in a time zone with more working hours that overlap those in Sweden – and he took that call in a timely fashion! We are deeply honored by this recognition of our discovery of the key driver of peripheral immune tolerance, which is required to maintain immune homeostasis.

My own career has taken various twists and turns since the small biotech company where Fred and I worked together closed its doors in early 2004. In the intervening years I have witnessed how, together with Shimon’s foundational work in the field, our discovery of the FOXP3 gene and its essential role in driving the development of regulatory T cells set in motion astonishing advances in our understanding of how the immune system both protects against foreign invaders and does NOT recognize and attack our own organs and tissues.

The past 20 years has seen remarkably innovative approaches to harnessing the power of the rare but mighty regulatory T cell. Today numerous clinical trials based on Treg cell activity are in various stages of progress to treat many of our most common and burdensome conditions, and the future for effective treatments and potentially cures, is now bright and hopeful.

Our story is typical, on the one hand, as one whose success depended on and expanded upon basic research advances over many decades. When Peter Medawar accepted the Nobel Prize in 1960 for first describing immune tolerance he said: if we today see further than our predecessors, it is only because we stand on their shoulders; and somewhat atypical in that the contributions from Fred and me came out of a small biotech operation. Although we were unable to pursue Treg cell biology ourselves within that same environment, we were able to publish our results, which were taken up by the scientific community in a way that I find both gratifying and humbling. Of course Shimon’s work that is being recognized was both preceded and followed by many other invaluable studies in the field. I want to highlight the powerful synergies between research efforts in academic labs and in the private sector. Each realm has its own unique strengths and the most significant advances in clinical applications come out of capitalizing and expanding upon those synergies.

Shimon, Fred and I gratefully acknowledge the many many research team members, collaborators, mentors, and funders who have supported us throughout our careers. We also couldn’t do what we did without the support of family and other colleagues. As a woman in science I especially want to acknowledge those role models who gave me the courage and incentive to persevere; my hope is that I in turn can be that role model for my own daughters, who are just now launching out into the world, as well as for other young women who are excited about science.

Thank you.

English

Swedish

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses,

Esteemed Laureates, Dear Colleagues,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

One and a half percent – this year’s prize in economic sciences is about the power of one and a half percent. Close to zero, you might think, but when it represents sustained economic growth, one and a half percent per year rather than zero means everything.

For most of the history of humankind, growth was negligible. Living conditions barely changed between generations. But over the last two centuries, steady economic growth of one and a half percent per year has instead become the norm, lifting masses of people from poverty, doubling life expectancy and laying the foundation for our welfare.

But what is economic growth about? Perhaps the word “more” comes to mind. More money, more work, more energy, more consumption, more of everything. During the first phases of growth, more was certainly important, and it still is in poor countries. There, more food, more medicine, more resources and more energy are required for a better livelihood.

But over time, the content of economic growth has evolved. In modern societies, it is no longer all that much about more – it is about “new” and “better”. This year’s laureates show that growth over the last two centuries comes from a steady stream of technological improvements. New medicines, safer cars, better food, better ways of heating and lighting our homes and new ways to communicate over great distances are just a few dimensions of economic growth. New and better products and methods replace the old ones in a process we call creative destruction. Over one or two centuries, almost everything changes.

Joel Mokyr demonstrated that for this process to work, practical knowledge must be intertwined with scientific understanding. Before growth started, the two types of knowledge were disconnected. In Mokyr’s own words: It was a world of engineering without mechanics, ironmaking without metallurgy, farming without soil science, mining without geology, waterpower without hydraulics and medical practice without microbiology and immunology.

This disconnect made it very hard to improve upon technological discoveries, be it in steel making, medical treatments such as vaccines or the value of doctors washing their hands before doing surgery. The Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution changed that. Scientific understanding about why things work became linked to practical knowledge about how things work. This produced a self-propelling spiral that gave us a continuous flow of new useful knowledge – a spiral that is still today producing new and better.

Creative destruction is turbulent. Firms and jobs are continuously destroyed and replaced. By inventing a mathematical model of the whole economy, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt showed that despite this turbulence, creative destruction results in steady growth, decade after decade. Their model and its further developments have become a laboratory producing a wealth of important lessons for society.

These include that markets left alone often provide too weak incentives for innovation, but also that incentives, in fact, can be too strong. And safety nets that help workers transition to new and better jobs should be provided.

Their work also shows that since new ideas build upon old ones, the direction of innovation is often persistent. It can get trapped along unwanted paths, such as the reliance on fossil fuels. The models show how society can then steer innovations in a sustainable direction.

Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt: You have uncovered the preconditions for and the mechanisms underlying innovation-driven growth. Your work provides society with a better chance to make sure that economic growth can continue and be directed to deliver new and better to humankind.

It is an honour and a privilege to convey to you, on behalf of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, our warmest congratulations. I now ask you to receive your prizes from His Majesty the King.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2025

English

English (pdf)

Norwegian

Norwegian (pdf)

Spanish

Spanish (pdf)

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation, Stockholm, 2025.

General permission is granted for the publication in newspapers in any language. Publication in periodicals or books, or in digital or electronic forms, otherwise than in summary, requires the consent of the Foundation. On all publications in full or in major parts the above underlined copyright notice must be applied.

Your Majesties,

Your Royal Highnesses,

Esteemed laureate,

Excellencies,

Distinguished guests,

Ladies and gentlemen,

Samantha Sofia Hernandez, a girl of 16, was brutally abducted last month by masked members of the Maduro regime’s security forces. She was taken from the home of her grandparents. Where she is now, we don’t know – probably in one of the dictatorship’s detention centres. She may be with her father, who disappeared without a trace in January.

What had they done wrong?

Her brother was a soldier, but refused to follow the regime’s orders to commit brutal acts against the population.

For that offence, the entire family must be punished.

Juan Requesens is ordered to turn slowly towards the camera. The video shows him standing with a dazed look, as if in a fog, wearing underwear stained with excrement. He had supposedly confessed to planning a coup. But of course, there was no proof. The day before his arrest, Juan had stood before the National Assembly. He gave a speech in which he repeated one key sentence, a promise to his country and to himself: “I refuse to give up.”

Alfredo Diaz, an opposition leader and former mayor, was pulled from a bus last November and thrown into the depths of El Helicoide, Latin America’s largest torture chamber. One more political prisoner, in a long line of others. This week came the news of his death. Another life gone. Another victim of the regime.

These stories are not unique. This is Venezuela today. It is how the Venezuelan regime treats its own people. A sister. A student. A politician. Anyone who still believes in stating the truth out loud may disappear violently into a system built specifically to eradicate this belief.

Samantha, Juan and Alfredo were not extremists. They were ordinary Venezuelans dreaming of freedom, democracy and rights.

For this, their lives were stolen from them.

Under this regime, children are not spared. More than 200 children were arrested after the election in 2024. The United Nations documented their experiences as follows:

Plastic bags pulled tight over their heads.

Electric shocks to the genitals.

Blows to the body so brutal that it hurt to breathe.

Sexualised violence.

Cells so cold as to cause intense shivering.

Foul drinking water, teeming with insects.

Screams that no one came to stop.

One child lay in the dark whispering his mother’s name, over and over, in the hope she would not believe he was dead.

A 16-year-old boy eventually came home, so ravaged by electric shocks and beatings that he could not hug his mother without pain shooting through his body. For months he jumped at every sound and barely slept. At night he would wake with a jolt – convinced the soldiers were back, to resume their attacks.

As we sit here in Oslo City Hall, innocent people are locked away in dark cells in Venezuela. They cannot hear the speeches given today – only the screams of prisoners being tortured.

This is how authoritarian powers try to crush those who stand up for democracy.

The United Nations has declared these acts to be crimes against humanity.

This is the regime of Nicolas Maduro.

Venezuela has evolved into a brutal, authoritarian state facing a deep humanitarian and economic crisis. Meanwhile, a small elite at the top – shielded by political power, weapons and legal impunity – enriches itself.

In the shadow of this crisis, thousands of women and children are forced into prostitution and human trafficking. Daughters simply disappear. Children become objects of trade in the hands of criminals who see human desperation as a business opportunity.

A quarter of the population has already fled the country – one of the world’s largest refugee crises.

Those who remain live under a regime that systematically silences, harasses and attacks the opposition.

Venezuela is not alone in this darkness. The world is on the wrong track. The authoritarians are gaining.

We must ask the inconvenient question:

Why is it so hard for us to preserve democracy – a form of government that was conceived to protect our freedom and peace?

When democracy loses, the result is more conflict, more violence, more war.

In 2024, more elections were held than in any previous year – but ever fewer are free and fair. The power of the law is misused. Independent media are silenced. Critics are imprisoned.

More and more countries, including those with long democratic traditions, are drifting towards authoritarianism and militarism.

Authoritarian regimes learn from each other. They share technology and propaganda systems. Behind Maduro stand Cuba, Russia, Iran, China and Hezbollah – providing weapons, surveillance and economic lifelines. They make the regime more robust, and more brutal.

And yet – amid this darkness – we find Venezuelans who have refused to give up. Those who keep the flame of democracy alive. Who never yield despite the enormous personal cost. They remind us continually of what is at stake.

Many of them are with us today:

Venezuela’s president elect, Edmundo Gonzalez Urrutia.

Carlos, the poet.

Claudia, the activist.

Pedro, the university professor.

Ana Luisa, the nurse.

Corina, the grandmother.

Antonio, the opposition politician.

Maria Corina, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

At the heart of the battle for democracy shines a simple truth: Democracy is more than a form of government. It is also the basis for lasting peace.

Millions of Venezuelans know this.

Year after year, students, trade unions, journalists, business groups and ordinary citizens have mobilised in waves of resistance.

They have filled the streets in protest. When their votes were taken away, they banged pots and pans. When state surveillance is inescapable, they whisper.

People across the political spectrum – from communists to conservatives – have risen to challenge the regime. The opposition has tried one strategy after another.

Through it all, they have said: We strive not for revenge, but for justice. For the sanctity of the ballot box. For democracy. For peace.

But they are told, in reply, that those things are impossible. That they will fail.

And when the Venezuelans asked the world to pay attention – we turned away.

As they lost their rights, their food, their health and safety – and eventually their own futures – much of the world stuck to old narratives. Some insisted Venezuela was an ideal egalitarian society. Others wanted only to see a struggle against imperialism. Still others chose to interpret Venezuelan reality as a contest between superpowers, overlooking the bravery of those who seek freedom in their own country. What all these observers have in common is this: the moral betrayal of those who actually live under this brutal regime.

If you only support people who share your political views, you have understood neither freedom nor democracy. Yet many critics stop there. They see local democratic forces cooperating, by necessity, with actors they dislike – and use that to justify withholding support. This puts ideological conviction ahead of human solidarity.

How should we regard those who use all their energy finding fault with the hard choices that brave defenders of democracy have had to make – instead of recognising their courage and their sacrifice, or asking how we, too, can help fight dictatorship?

It is easy to stand on principle when someone else’s freedom is at stake. But no democracy movement operates in ideal circumstances. Activist leaders must confront and resolve dilemmas that we onlookers are free to ignore. People living under dictatorship often have to choose between the difficult and the impossible. Yet many of us – from a safe distance – expect Venezuela’s democratic leaders to pursue their aims with a moral purity their opponents never display. This is unrealistic. It is unfair. And it shows ignorance of history.

Many who have stood at this podium to receive the Nobel Peace Prize – including Lech Walesa and Nelson Mandela – knew well the dilemmas of dialogue.

In authoritarian systems, dialogue can lead to improvement – but it can also be a trap. Dialogue is often used to buy time, create division and control the agenda. Maria Corina Machado has participated in dialogue processes for years. She has never rejected the principle of talking to the other side ¬– but she has dismissed empty processes.

Peace without justice is not peace.

Dialogue without truth is not reconciliation.

Venezuela’s future can take many forms. But the present is one thing only – and it is horrific.

This is why the democratic opposition in Venezuela must have our support – not our indifference, or worse, condemnation. Every day, its leaders must choose a path that is in fact open to them, not the path of wishful thinking.

Support for democratic development is support for peace.

But since the announcement of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize, the question has been posed: Does democracy really lead to peace?

The research findings are crystal clear, and the answer is yes. Not because democracy is perfect, but because the mechanisms of democracy make war less likely.

Democracies are equipped with safety valves: free media, power-sharing structures, independent courts, civil society organisations and elections that make it possible to change leadership without violence. In this political environment, differing opinions are not a threat to be put down, but an advantage.

In a democracy, a leader who ignores facts can be replaced in the next election. In an authoritarian regime, the leader stays in power – and replaces all who tell uncomfortable truths. Loyalty takes the place of reality, and dangerous decisions are taken in the dark. War is always costly – but in authoritarian regimes, it is not the leaders who pay the highest price. This is why democracies almost never go to war with each other, as authoritarian states are more prone to do.

Nicolas Maduro’s rule in Venezuela shows why. Conflicts are resolved with brute force, not negotiation. The result is a society where millions are forced into silence, with consequences that do not stop at the border. Instability, violence and systematic destruction of the country’s institutions have affected the entire region, and a neighbouring country has been threatened with military invasion. Venezuela demonstrates – with painful clarity – that authoritarian rule both destroys society from within and spreads instability abroad.

Democracy is obviously no guarantee of peace, but it is the most effective system we have to prevent violence and conflict.

This line of reasoning often prompts a well-known counterargument: that democracy itself causes unrest and conflict – that demanding freedom is dangerous. This is an old claim. Authoritarian leaders have used it for generations to defend their positions of power. Today they supercharge the argument with disinformation and propaganda – two of their essential weapons.

Ladies and gentlemen,

As citizens in a democracy we have a duty to be critical of information sources. Alarm bells should ring when the views we express are identical to those disseminated by one of the world’s most manipulative disinformation systems. For in that case, we are not just spreading information, we are spreading the strategic propaganda of a dictator.

What are we all to think when we read that it is the Venezuelan opposition that’s threatening the country with war – that the democratic movement desires an invasion? When the narrative is turned upside down, and the victims are branded aggressors? This is the version of reality the Maduro regime tells the world: that it is the guarantor of peace. But peace based on fear, silence and torture – is no peace. It is submission, depicted as stability.

No, the source of the violence is not democracy activists. It is those at the top who refuse to cede power. It was not Nelson Mandela who made South Africa violent, but the apartheid regime’s crackdown on demands for equality. Opposition groups did not start the imprisonments in Belarus, the executions in Iran – or the persecution in Venezuela. The violence comes from authoritarian regimes, as they lash out against popular calls for change.

Peace and democracy cannot be separated without draining both of meaning. Lasting peace depends on the rule of law, political participation and respect for human dignity.

Before we can discuss our political disagreements, we must establish some form of democracy. Without it, there is no meaningful distinction between right and left, no way to legitimately disagree, no genuine politics.

Democracy is not an expendable luxury.

It is not an ornament to put on a shelf.

Democracy is hard work.

It is action and negotiation.

It is a living obligation.

The instruments of democracy are the instruments of peace.

We gather today, therefore, to defend something far more important than either side of a political or ideological divide. We gather to defend democracy itself – the very foundation on which lasting peace rests.

When people refuse to surrender democracy, they refuse to surrender peace. One who understands this is Maria Corina Machado.

As a founder of Súmate, an organisation devoted to building democracy, Ms Machado stepped forward to advocate free and fair elections more than two decades ago. As she herself put it: “It was a choice of ballots over bullets.”

In political office and in her service to organisations, Ms Machado has spoken out for judicial independence, human rights and popular representation. She has spent years working for the freedom of the Venezuelan people.

The presidential election of 2024 was a key factor in the selection of this year’s Peace Prize laureate. Ms Machado was the opposition’s presidential candidate – and the country’s unifying voice of hope. When the regime blocked her candidacy, the movement might have collapsed, but she threw her support behind Edmundo Gonzalez Urrutia and the opposition stayed together.

The opposition found common ground in the demand for free elections and representative government. This is the very foundation of democracy: our shared willingness to defend the principles of popular rule, even if we disagree on policy. At a time when democracy is under threat around the world, it is more important than ever to defend this common ground.

Hundreds of thousands of volunteers mobilised across political divides. They were trained as election observers and used technology in new ways to document each step in the election. Up to a million people stood watch over polling stations around the country. They uploaded vote tallies, photographed records and secured copies before the regime could destroy them. They defended this documentation with their lives, then made sure the world learned the results of the election.

This was grassroots mobilisation unlike any that Venezuela, and probably the world, had ever seen. Ordinary citizens from all walks of life carrying out systematic, high-tech documentary work in an atmosphere of threats, surveillance and violence.

The efforts of this democracy movement, both before and after the election, were innovative and brave, peaceful and democratic.

The opposition received international support when its leaders publicised the vote counts that were collected from the country’s election districts, showing that the opposition had won by a clear margin.

But the regime denied it all. It falsified the election results and clung to power – violently.

For the past year, Ms Machado has had to live in hiding.

Despite serious threats, she has remained in the country – an inspiration to millions.

She is receiving the Nobel Peace Prize for 2025 for her tireless work promoting democratic rights for the people of Venezuela and for her struggle to achieve a peaceful and just transition from dictatorship to democracy.

For a long, long time, the opposition in Venezuela has relied on democracy’s toolbox to wage its peaceful civilian campaign. Over the years, Ms Machado and her allies have had to adapt and change tactics. They have applied almost every democratic tool: from election boycotts when the system was too rotten, to participation when small openings in the process made it possible. They have tried dialogue, organisation, mobilisation and extensive election documentation.

Ms Machado has appealed for international attention, support and pressure – not for an invasion of Venezuela.

She has urged people to stand up for their rights using peaceful, democratic means.

Peace research shows it clearly: Widespread non-violent mobilisation is among the most effective methods of achieving political change in a dictatorship. When a population mobilises, and the international community exerts strong pressure, and the security forces refrain from using violence against the population – a tipping point may arrive.

As the leader of the democracy movement in Venezuela, Maria Corina Machado is one of the most extraordinary examples of civilian courage in recent Latin American history.

This year’s Nobel Peace Prize fulfils all three of the criteria stated in Alfred Nobel’s will.

First, the Venezuelan opposition has united political movements, civil society organisations and ordinary citizens in pursuit of one goal: the restoration of democracy. Pulling together diverse groups that previously opposed one another is the modern equivalent of what Alfred Nobel called holding peace congresses.

Second, Venezuela’s democracy movement has opposed the regime’s militarisation of society. The regime has armed thousands of groups, authorised paramilitary bands to commit abuses and invited foreign military forces into the country, thereby accelerating the militarisation. By documenting abuses and demanding accountability, the opposition seeks to strengthen civilian democratic authority and roll back the influence of weapons. This deprives criminals and regime-friendly militias of their arms and autonomy – and satisfies Nobel’s criterion of seeking peace through disarmament.

Third, true fraternity or fellowship – the kind Alfred Nobel envisaged – requires democracy. Only when people are able to choose their leaders and speak without fear can peace take root, whether inside a society or between countries. Democracy is the highest form of fellowship, and the surest way to lasting peace.

Therefore, here today, in this hall – with all the gravity that attends the Nobel Peace Prize and this annual ceremony – we will say what authoritarian leaders fear most:

Your power is not permanent.

Your violence will not prevail over people who rise and resist.

Mr Maduro,

You should accept the election results and step down.

Lay the foundation for a peaceful transition to democracy.

Because that is the will of the Venezuelan people.

Maria Corina Machado and the Venezuelan opposition have lit a flame that no torture, no lie and no fear can extinguish.

When the history of our time is written, it won’t be the names of the authoritarian rulers that stand out – but the names of those who dared resist.

Those who stood tall in the face of danger.

Those who kept going, when others gave up.

In its long history, the Norwegian Nobel Committee has honoured brave women and men who have stood up against repression, who have carried the hope of freedom in prison cells, in the streets and in public squares, and shown by these actions that resistance can change the world.

Today, we honour you, Maria Corina Machado.

We pay tribute as well to all who wait in the dark.

All who have been arrested and tortured, or have disappeared.

All who continue to hope.

All those in Caracas and other cities of Venezuela who are forced to whisper the language of freedom.

May they hear us now.

May they realise that the world is not turning away.

That freedom is drawing closer.

And that Venezuela will become peaceful and democratic.

Let a new age dawn.

This year, chef duo Tommy Myllymäki and Pi Le will be in charge of the first and main course for the 1,300 guests in the Blue Hall on 10 December. They are joined by Frida Bäcke, who for the second year in a row will create the evening’s dessert. The menu will include mushrooms and berries from the forest, with a focus on unexpected taste sensations. A new piece of cutlery is also introduced during the evening – a butter knife made of carved oak from the south of Sweden.

Pi Le and Tommy Myllymäki run the restaurant Aira in Stockholm, which has been awarded two Michelin stars, as well as Bobergs Matsal and Nordiska Kantinen at the NK department store. The two chefs are used to working together and find that being a duo comes with many advantages.

“Being a duo is beneficial, not only at the conceptual stage but also when it comes to implementation. We complement each other very well – Tommy contributes with his enthusiasm and never says ‘we can’t do that.’ At the same time, we tend to say that I’m the one making sure that the ideas are turned into concrete results. I believe that this combination is incredibly valuable,” says Pi Le.

How do they view this task?

“What’s unique with this task is that it comes with such an incredibly strong historical heritage, while at the same time showcasing gastronomic innovation. For us, this is always ultimately about creating an amazing taste sensation – and preferably with unexpected taste combinations. We tend to say that we move on a scale between safety and innovation in our work. Comfort gets to meet creativity. The food should feel familiar but with a twist, something unexpected,” says Tommy Myllymäki.

The menu is secret until the guests sit down at their tables on 10 December. However, the laureates and guests will, for example, get to taste what the Swedish forest has to offer. The first course includes dried porcini mushroom, which offers an intense taste sensation and sets the tone for the dish. The dessert will include wild raspberries and blackthorn berries.

Frida Bäcke runs the patisserie Socker Sucker in Stockholm and has been named the Swedish Pastry Chef of the Pastry Chefs several times.

“It is a great honour that I have once again been asked to do this. Working with the Nobel Prize banquet last year was one of the most exciting things I have done in my life. This year, we have decided to be inspired by nature and the Swedish forest. I love wild raspberries and have fond childhood memories of how I used to pick them together with my grandparents. I enjoy drawing attention to blackthorn berries. It is a berry that ripens late and is picked at the first frost,” she says.

She is very familiar with the chefs from previous jobs.

“It feels great to once again work together. Tommy and Pi make up a really good team in terms of both technique and creativity, and I share a lot of their ideas. We have created dishes together at Aira, and doing it again for the Nobel Prize banquet feels great,” says Bäcke.

The current Nobel tableware was created more than 30 years ago and has looked the same ever since. A new piece of cutlery is introduced this year in the form of a hand-carved butter knife, developed by Pi Le’s brother Van Le in collaboration with the chef duo. The butter knives are made of oak from the south of Sweden, and each knife has been sanded by hand. In total, no fewer than 1,300 butter knives will be ready by 10 December.

Pi Le moved to Ängelholm from Vietnam together with his family when he was two years old. Between 2011 and 2014, he was part of the Junior National Culinary Team, where he won a Culinary Olympic gold medal in 2012 and a Culinary World Cup silver medal in 2014, as well as coming in second individually in the 2011 Nordic Chef of the Year. Following that, he was part of the Swedish National Culinary Team between 2014 and 2016. Pi Le currently operates several restaurants together with Tommy Myllymäki, including the two-star restaurant Aira, where he is also a partner, as well as the traditional Bobergs Matsal and the salad bar concept Akvileja.

Tommy Myllymäki grew up in Katrineholm in Södermanland and has been a prominent figure in Swedish gastronomy since 2007, when he was named Chef of the Year. He has successfully competed internationally in the Bocuse d’Or, winning a gold medal in Bocuse d’Or Europe in 2014 and a silver and a bronze medal in the world finals in 2011 and 2015. Tommy has since 2023 served as a judge on the television show Sveriges Mästerkock (Swedish Master Chef), and he has also written and published seven cookbooks. Tommy currently operates a number of restaurants together with Pi Le, including the two-star restaurant Aira in Stockholm, the classic Bobergs Matsal at the NK department store in Stockholm and the salad bar concept Akvileja.

Frida Bäcke grew up in Västerby outside of Hedemora. She has served as the pastry chef at restaurants such as Franzén and Aira. She was part of the Swedish National Culinary Team for five years and has competed in both the Culinary World Cup and the Culinary Olympics. Frida has, for four years in a row, been named the Swedish Pastry Chef of the Pastry Chefs. The patisserie Socker Sucker, which she operates together with her colleague Bedros Kabranian, has also been awarded the Swedish Patisserie of the Patisseries for three consecutive years.

More images here: link to Nobel Week 2025 image folder

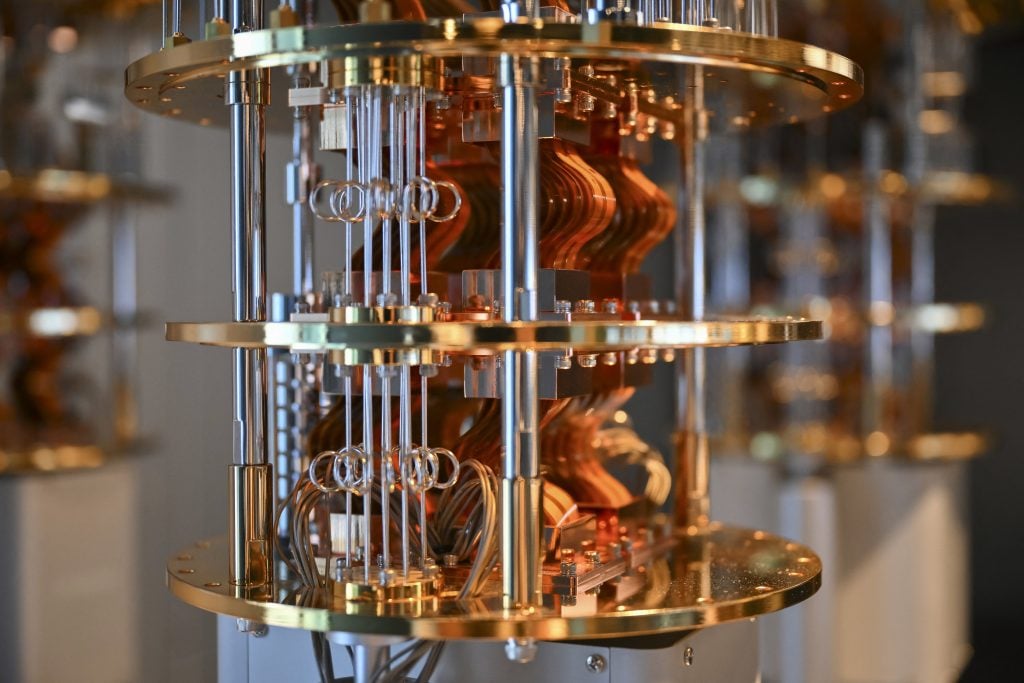

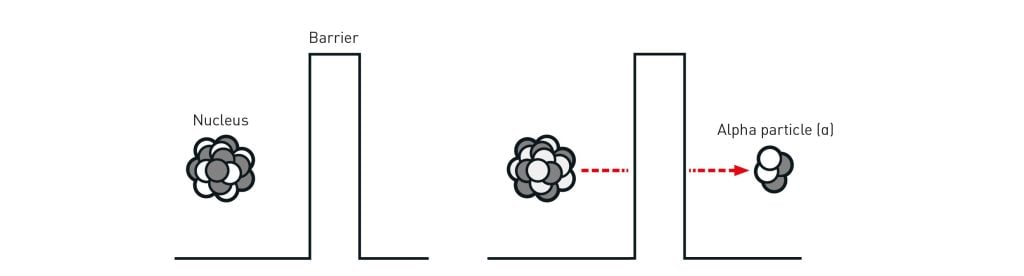

Although still in its early stages, quantum computing is advancing rapidly, along with quantum technologies as a whole. Nobel Prize-awarded work on entangled quantum states and quantum mechanical tunnelling were driving forces behind this progress. Applications of quantum technologies are anticipated to improve our daily lives and contribute to solving global challenges.

Quantum mechanics underpins our understanding of the physical world. The theory that would revolutionise physics was born in the summer of 1925 when 23-year-old Werner Heisenberg, looking for relief from his extreme hay fever on the remote island of Helgoland, formulated the theory of quantum mechanics.

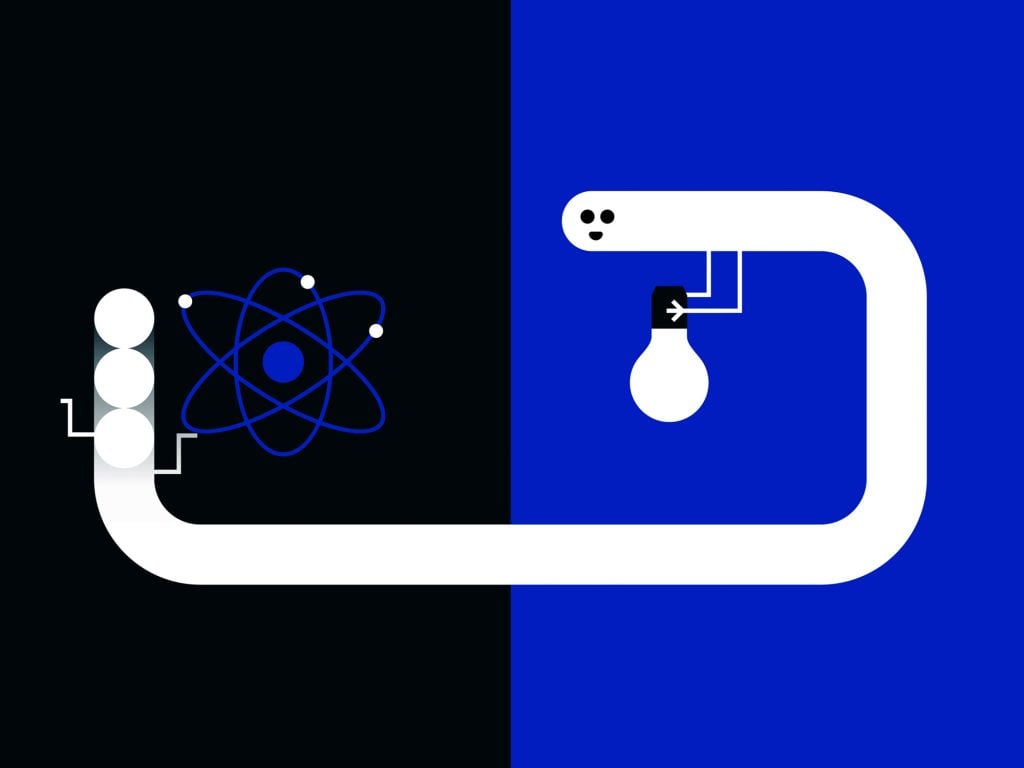

The transition from theory to technology during the ‘first quantum revolution’ led to transformative innovations such as lasers, MRI scanners, and integrated circuits. We are now experiencing a ‘second quantum revolution’ – a shift from explaining quantum mechanics to creating artificial quantum states.

The second quantum revolution began in the 1960s. For a long time, the pioneers within quantum physics had tried to understand the phenomenon of entanglement: how two separated particles could remain connected even though they might be far away from each other, something physics titan Albert Einstein called “spooky action at a distance.” Quantum entanglement seemed to conflict with Einstein’s theory of special relativity, which postulates that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light.

In 1964, John Stewart Bell proposed a theory showing that quantum entanglement is incompatible with Einstein’s notion of locality and causality. Inspired by Bell, while still a graduate student, John Clauser managed to transform Bell’s theorem into a very specific mathematical prediction. Through later experiments, Clauser was able to confirm that quantum entanglement is real. The result came somewhat as a surprise to Clauser, who had made a bet for the ‘Einstein side’ to win.

“I was very sad to see that my experiment had proven Einstein wrong,” John Clauser said.

However, Clauser’s results were not iron-clad. Building on his work, French doctoral student Alain Aspect closed an important loophole and provided a very clear result: quantum mechanics is correct. Experiments on quantum teleportation, the way of transferring an unknown quantum state from one particle to another, by Anton Zeilinger and his colleagues were also crucial for our understanding of entangled quantum states. Quantum teleportation has become a powerful tool that is used daily in labs all around the world and with some demonstrations in real-world fibre optics.

“Their work was fundamental. These experiments meant that the quantum physics community could actually use this concept in practical applications,” says Sofia Vallecorsa, coordinator of the CERN Quantum Technology Initiative.

Quantum entanglement is important in all main areas of quantum technology listed in the EU launched initiative Quantum Technology Flagship: quantum computing, quantum simulation, quantum communication and quantum metrology and sensing. These technologies are anticipated to revolutionise numerous industries, address global challenges and improve our daily lives.

An example of quantum communication is quantum key distribution, QKD, which has been in commercial use for a number of years and might be the most mature quantum technology. QKD enables secure communication by providing a method to securely exchange encryption keys. This is used by various actors such as banks and companies within healthcare and is seen as the first step towards a future global ‘quantum internet’ – interconnected quantum computers that may allow people to send, compute, and receive information using quantum technology.

Quantum simulators will allow us to overcome the limitations of supercomputers, enabling the modelling of materials or chemical compounds.

Quantum sensing allows for measurement of physical quantities like time, gravity, and magnetic fields with extremely high precision. One useful application of quantum sensors is the ability to enhance speed and quality of MRI scans.

In the future, your smartphone may use a variety of quantum technologies. Quantum sensors may improve the navigation system to help you find your way around. Quantum key distribution might enable you to communicate in a secure way. Quantum simulations may lead to mobile phone batteries that last longer. Quantum computers may be useful if you can access their services through the internet, for example providing you with the best routes in congested traffic.

Source: Quantum Technology Flagship

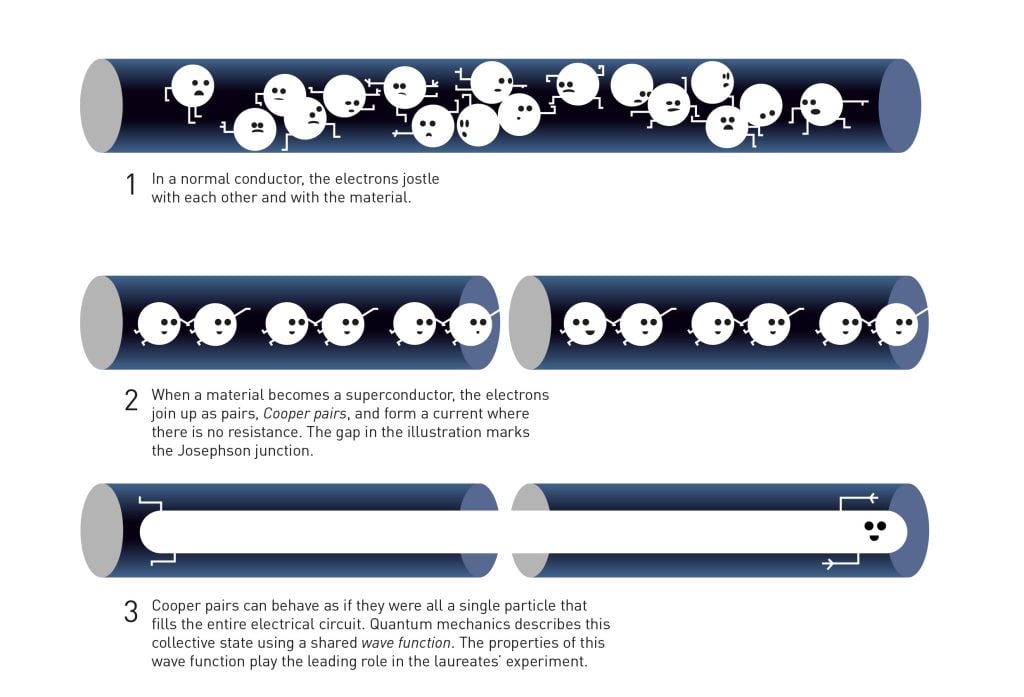

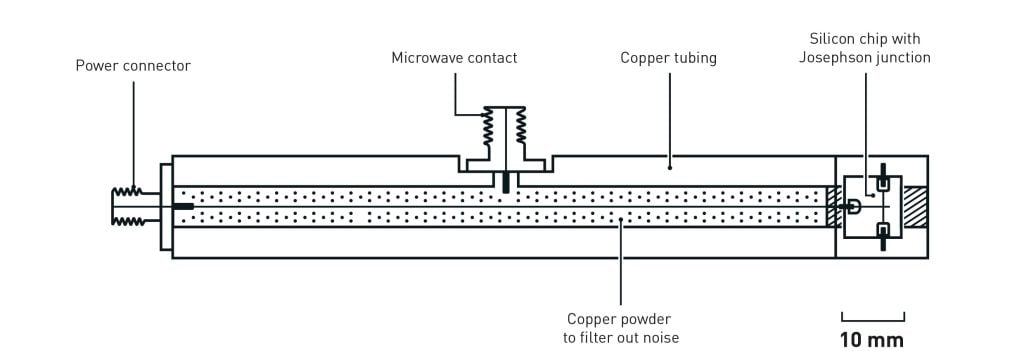

Macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling, recognised in the Nobel Prize in Physics 2025, is the mechanism behind superconducting qubits used in quantum computers. Qubits, unlike binary bits in classical computers, can exist in multiple states at the same time due to superposition.

In recent years, Vallecorsa and her colleagues working with quantum technologies at CERN, have observed rapid progress in quantum computing, driven by the potential it can offer in the acceleration of complex computing problems.

In 2023, the highest-energy observation of quantum entanglement to date was reported by the ATLAS experiment, performed at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator. This record measurement, later confirmed by the CMS experiment at the LHC, opened up new ways to test the fundamental properties of quantum mechanics.

While CERN is testing the use of quantum computing for simulating physical processes and analysing experimental data, Vallecorsa closely monitors the rapid development of quantum computing applications.

Improving certain tasks in large classical infrastructure, optimising logistics pipelines in big industrial complexes and quantum chemistry are some examples that profit from quantum computing, says Vallecorsa. Healthcare is another promising field, where advanced calculations could facilitate faster drug discovery.

“If we manage, the potential is great.”

Sofia Vallecorsa, CERN

Numerous initiatives that promote the development of quantum computing applications for the benefit of humanity are underway. The Open Quantum Institute, hosted by CERN, born at the Geneva Science and Diplomacy Anticipator (GESDA), supported by UBS, explores possible applications within a broad field, from predicting gastrointestinal cancer to detecting water leaks in urban water systems. In chemistry, quantum computing could lead to a better understanding and new innovations which would benefit the fertiliser production.

Law enforcement agencies are also paying close attention. Quantum computing has the potential to revolutionise forensics and security practices – but it also poses risks, such as the potential to break cryptography.

We are still far from a perfect quantum computer, since the qubits – the building blocks of quantum computers – are unstable and undergo “decoherence” when they interact with their environment. To overcome these limitations, major tech players are exploring quantum error correction (QEC), which is a way of detecting and fixing errors while preserving quantum coherence.

Funding and talent shortages are other challenges. While still in its infancy, expectations on how quantum computing can transform the world are high, with potentially great impact on global challenges. Vallecorsa shares the excitement – but is also cautious:

“Just like artificial intelligence is having a very strong impact on us, quantum computing and quantum technologies in general are next – because the potential is very large. However, too much hype can hurt the technology because it raises expectations to a level where if it doesn’t live up to it, the trust in the technology is lost. But if we manage, the potential is great.”

Published November 2025

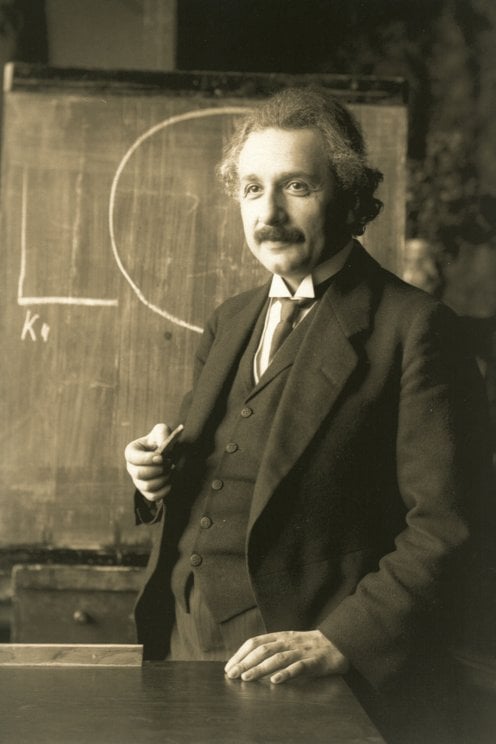

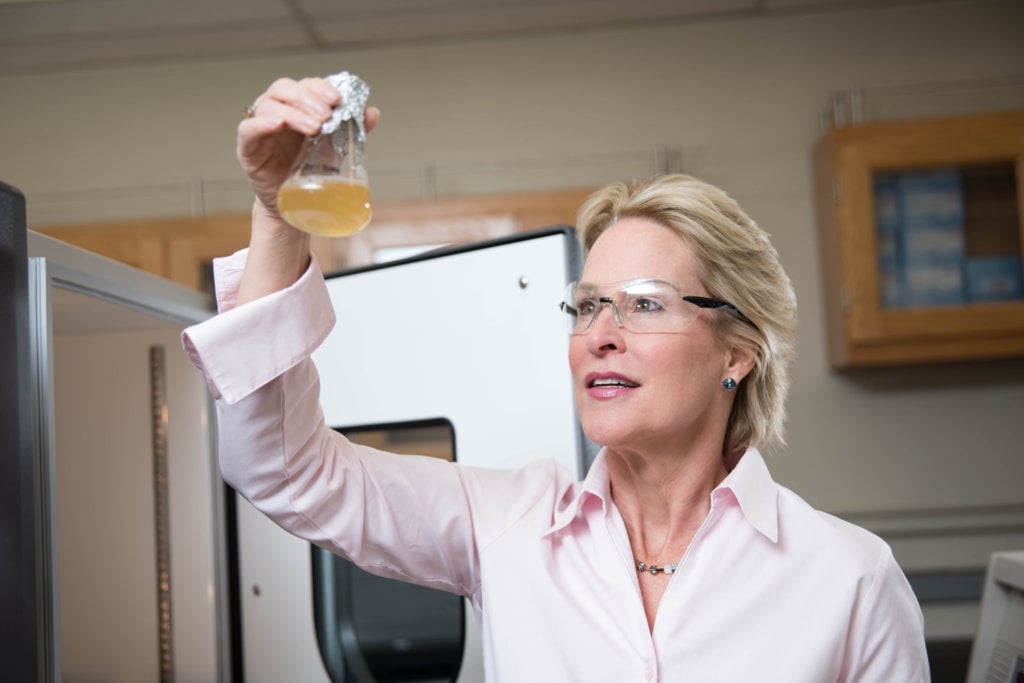

The risk of losing free flow of ideas and people is one of the most pressing challenges for science, says 2018 chemistry laureate Frances Arnold. In this interview, she also elaborates on the importance of enzymes in healthcare, the promises of AI and the uses of “useless” knowledge in science.

How important is basic research in creating better healthcare for all?

“To answer that, we need to look at today’s medicine, which is based on basic scientific discoveries that were made in the past. I would say that we are just scratching the surface of understanding the biological world. We are just at the beginning of that, so there’s a lot more basic research to be done that will undoubtedly lead to better healthcare.”

What needs to be done when it comes to funding of basic research?

“I think that people need to understand that basic research is an investment. It’s an investment in our future, and taxpayers who pay for that have a right to know that their money is being spent wisely on that investment. For me, that means a focus on excellence, perhaps targeting use-inspired basic research in particular areas that we know would be rich for discoveries. It’s also important that the people who receive such funding know that they have an obligation to make the results of that investment available to the public and to other scientists. It’s not a one-way street.”

What can the scientific community do to better explain the benefits of science?

“There’s a lot of improvement to be done. Scientists as a community can try to become better communicators. Often, we are teachers and we communicate to students, but we also need to communicate to the public that pays for the science. We need to lose the idea that a scientist is entitled to funding merely because he or she works hard.”

“We’re not entitled to the hard-earned money of the taxpayers, we need to deserve that, which means we need to make the return on the investment available for future discoveries and future development.”

Frances Arnold

What are the most pressing challenges faced by science today?

“In addition to the obvious reduction in the investment in science, especially on the part of the US Federal Government, there’s a significant challenge to the free flow of ideas and people happening now. Science thrives when ideas are exchanged, and international collaborations are critical, which also includes the exchange of researchers. If we silo science in separate countries, then we lose much of this dynamic and the progress it fuels. The connection between international discussion and collaboration is what makes science move forward.”

From your experience, how can we tell what type of research will lead to having an impact on our lives and which won’t?

“It is very hard to tell, because surprises happen. Funders tend to favour some areas over others, because they want to cure a certain disease or they want to have a certain outcome. So, you get this use-inspired basic research. But I think it’s important to have a portfolio of research in areas that we know are important, but also to have some blue-sky research. If you work with a focus on excellence, then some researchers might be able to argue that their blue-sky work is worth supporting.”

Is there any such thing as useless knowledge in science?

“The answer is probably yes, but no one knows which knowledge is useless because we don’t know what the future holds. It’s conceivable that certain knowledge will never have utility other than fulfilling our human need to understand who we are, where we come from and where we’re going. That’s hardly useless, right?”

You have used the ideas of evolution to build new enzymes. How can these be used in healthcare and medicine?

“There are probably hundreds of examples where enzymes have been used in healthcare and medicine. Enzymes are used in medical diagnostics like glucose sensors, in DNA sequencing to understand our genomes, our predilection to disease and where we come from. Enzymes are therapeutics to treat disease and to manufacture pharmaceuticals cleanly.”

How do you feel about that something you helped create has impacted people’s lives and health? Is there anything that you are particularly proud of?

“I feel great about it. I think these applications are wonderful. I think when enzymes are used to solve human problems, especially if they’ve been fine-tuned by directed evolution, I’m proud that we are using the treasures of the biological world to make our lives better. In my own research, I use enzymes to manufacture pharmaceuticals, and that reduces waste and our footprint on the planet.”

“I feel very proud of being able to use biology to make what we need in our daily lives and to do it with a much cleaner footprint than we have in the past.”

Frances Arnold

Has AI helped you in your scientific research and do you see it playing a part in making scientific outcomes open to more people?

“Machine learning and AI are big parts of my research programme and have been for more than a decade. I’d say half my group is deeply involved in developing new tools of machine learning and AI and applying those tools to protein design and evolution. That’s not surprising because evolution is an algorithmic process. It’s very similar to active learning and machine learning. So, it was a natural flow to use our data in machine learning algorithms. With the Nobel Prize last year to David Baker, AI is now creating proteins. Those are great starting points for evolution. This all blends very nicely with directed evolution.

When it comes to using AI for communication of results, the large language models make writing and research a lot easier for people. Research a lot easier. So of course, AI is going to help in the communication of results as long as we keep the AI truthful and accurate.”

Frances Arnold is participating at this year’s Nobel Week Dialogue on 9 December in Gothenburg. The event will be live streamed here on nobelprize.org. Read more about the event here.

Published October 2025

Popular science background: From stagnation to sustained growth (pdf)

Populärvetenskaplig information: Från stagnation till stadig tillväxt (pdf)

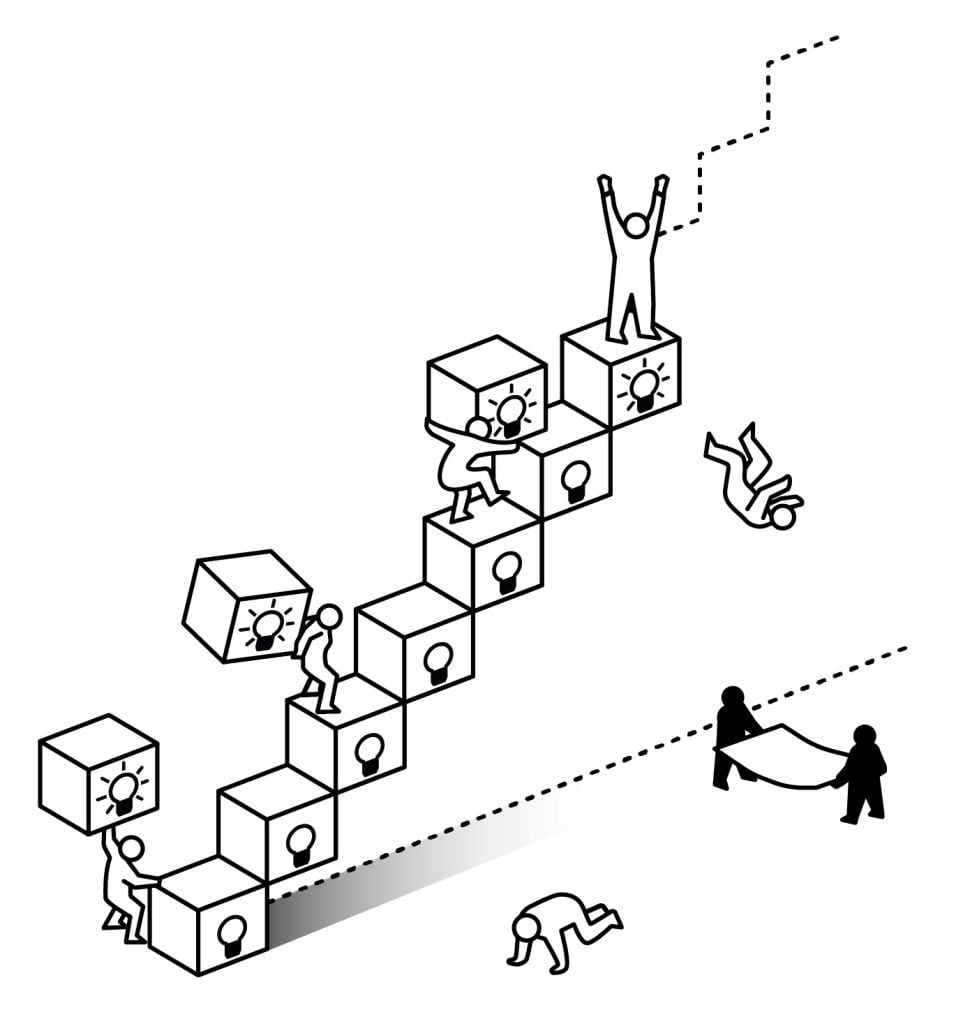

Over the past 200 years, the world has witnessed more economic growth than ever before. Its foundation is the constant flow of technological innovation; sustained economic growth occurs when new technologies replace old ones as part of the process known as creative destruction. This year’s laureates in economic sciences explain, using different methods, why this development was possible and what is necessary for continued growth.

For most of humankind’s history, living standards did not change considerably from one generation to the next, despite sporadic important discoveries. These sometimes led to improved quality of life, but growth always stopped eventually.

This was fundamentally changed by the Industrial Revolution, which occurred a little more than two centuries ago. Starting in Britain, and then progressing to other countries, technological innovation and scientific progress resulted in a never-ending cycle of innovation and progress, rather than isolated events. This led to sustained and remarkably stable growth.

This year’s prize relates to the explanations for sustained growth based on technological innovation. Economic historian Joel Mokyr is rewarded with one half of the prize for his description of the mechanisms that enable scientific breakthroughs and practical applications to enhance each other and create a self-generating process, leading to sustained economic growth. Because this is a process that challenges prevailing interests, he also demonstrates the importance of a society that is open to new ideas and permits change.

The other half of the prize is awarded to the economists Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt. In a joint publication from 1992, they constructed a mathematical model of how companies invest in improved production processes and new, better-quality products, while the companies that previously had the best products are outcompeted. Growth arises through creative destruction. This process is creative because it builds upon innovation, but it is also destructive because older products become obsolete and lose their commercial value. Over time, this process has fundamentally changed our societies – over the span of one or two centuries, almost everything has changed.

Economists measure economic growth by calculating increases in gross domestic product (GDP) but, actually, it involves much more than just money. New medicines, safer cars, better food, more efficient ways of heating and lighting our homes, the internet and increased opportunities for communication with other people over greater distances – these are just a few of the things included in growth.

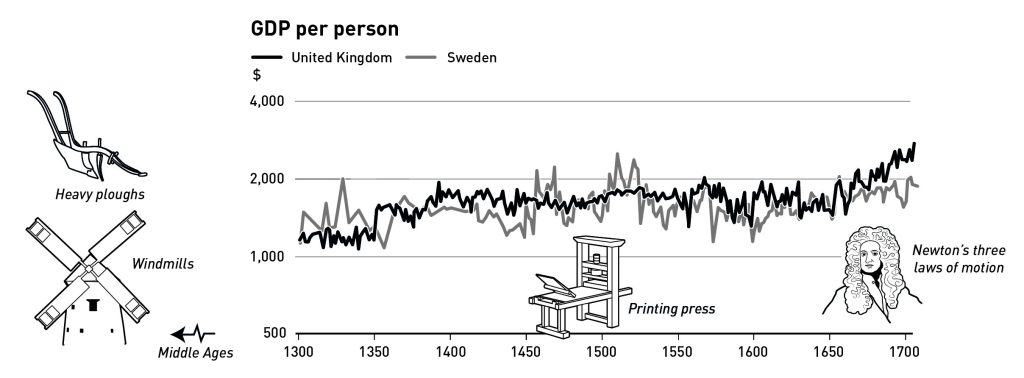

However, as we have said, economic growth based on technological development was not the historical norm – quite the opposite. One example of this is the trend in Sweden and Britain from the early 14th century to the start of the 18th century. Income sometimes rose and sometimes fell but, overall, there was almost indiscernible growth, despite important innovation occurring.

These discoveries thus had no noticeable effect on long-run economic growth. According to Mokyr, this is because the new ideas did not continue to evolve or lead to the flow of improvements and new applications that we now take for granted, as a natural consequence of major technological and scientific advancements.

Instead, when we look at economic growth in Britain and Sweden from the start of the 19th century to the present day, we see something entirely different. Apart from easily identifiable episodes such as the Great Depression in the 1930s and other crises, growth – rather than stagnation – has become the new normal. A similar pattern, with sustained annual growth of almost two per cent, arose in many industrialised nations after the early 19th century. It may not sound like much, but sustained growth at that level means a doubling of income over a person’s working life. Eventually, this has a revolutionary effect on the world and on people’s quality of life.

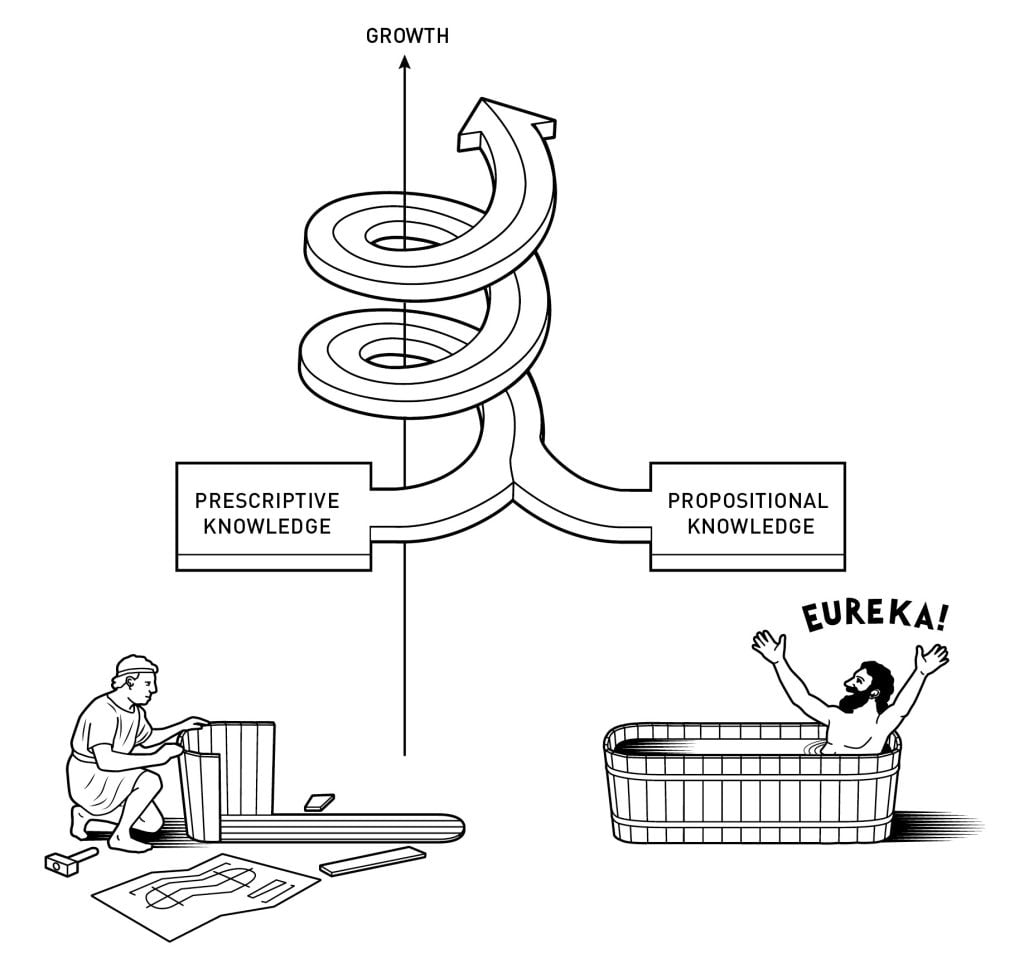

So – what creates this sustained economic growth? This year’s laureates used different methods to answer this question. Through his research in economic history, Joel Mokyr has demonstrated that a continual flow of useful knowledge is necessary. This useful knowledge has two parts: the first is what Mokyr refers to as propositional knowledge, a systematic description of regularities in the natural world that demonstrate why something works; the second is prescriptive knowledge, such as practical instructions, drawings or recipes that describe what is necessary for something to work.

Mokyr shows that prior to the Industrial Revolution, technological innovation was primarily based on prescriptive knowledge. People knew that something worked, but not why. Propositional knowledge, such as in mathematics and natural philosophy, was developed without reference to prescriptive knowledge, which made it difficult, even impossible, to build upon existing knowledge. Attempted innovations were often haphazard or had approaches that someone with adequate propositional knowledge would have understood were futile – such as building a perpetual motion machine or using alchemy to make gold.

The 16th and 17th centuries witnessed the Scientific Revolution as part of the Enlightenment. Scientists began to insist upon precise measurement methods, controlled experiments, and that results should be reproducible, leading to improved feedback between propositional and prescriptive knowledge. This increased the accumulation of useful knowledge that could be utilised in the production of goods and services. Typical examples include how the steam engine was improved thanks to contemporaneous insights into atmospheric pressure and vacuums, and advances in steel production due to the understanding of how oxygen reduces the carbon content of molten pig iron. Gains in useful knowledge facilitated the improvement of existing inventions and provided them with new areas of use.

However, if new ideas are to be realised, practical, technical and, not least, commercial knowledge are all necessary. Without these, even the most brilliant ideas will remain on the drawing board, such as Leonardo da Vinci’s helicopter designs. Mokyr stressed that sustained growth first occurred in Britain because it was home to many skilled artisans and engineers. They were able to understand designs and transform ideas into commercial products, and this was vital in achieving sustained growth.

Another factor that Mokyr claims is necessary for sustained growth is that society is open to change. Growth based upon technological change not only creates winners, it also creates losers. New inventions replace old technologies and can destroy existing structures and ways of working. He also showed that this is why new technology is often met with resistance from established interest groups who feel their privileges are threatened.

The Enlightenment brought a generally increased acceptance of change. New institutions, such as the British Parliament, did not provide the same opportunities for those with privilege to block change. Instead, representatives from interest groups had the opportunity to gather and reach mutually beneficial compromises. These changes to societal institutions removed a major barrier to sustained growth.

Propositional knowledge can sometimes also contribute to reducing resistance to new ideas. In the 19th century, Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis realised that maternal mortality rates dropped drastically if physicians and other staff washed their hands. If he had known why and been able to prove the existence of dangerous bacteria that are killed by handwashing, his ideas may have had an earlier impact.

Joel Mokyr used historical observations to identify the factors necessary for sustained growth. Instead, inspired by modern data, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt constructed a mathematical economic model that shows how technological advancement leads to sustained growth. These approaches are different, but fundamentally they deal with the same questions and phenomena.

As we have seen above, economic growth in industrialised nations such as Britain and Sweden has been remarkably stable. However, below the surface, the reality is anything but stable. In the US, for example, over ten per cent of all companies go out of business every year, and just as many are started. Among the remaining businesses, a large number of jobs are created or disappear every year; even if these figures are not as high in other countries, the pattern is the same.

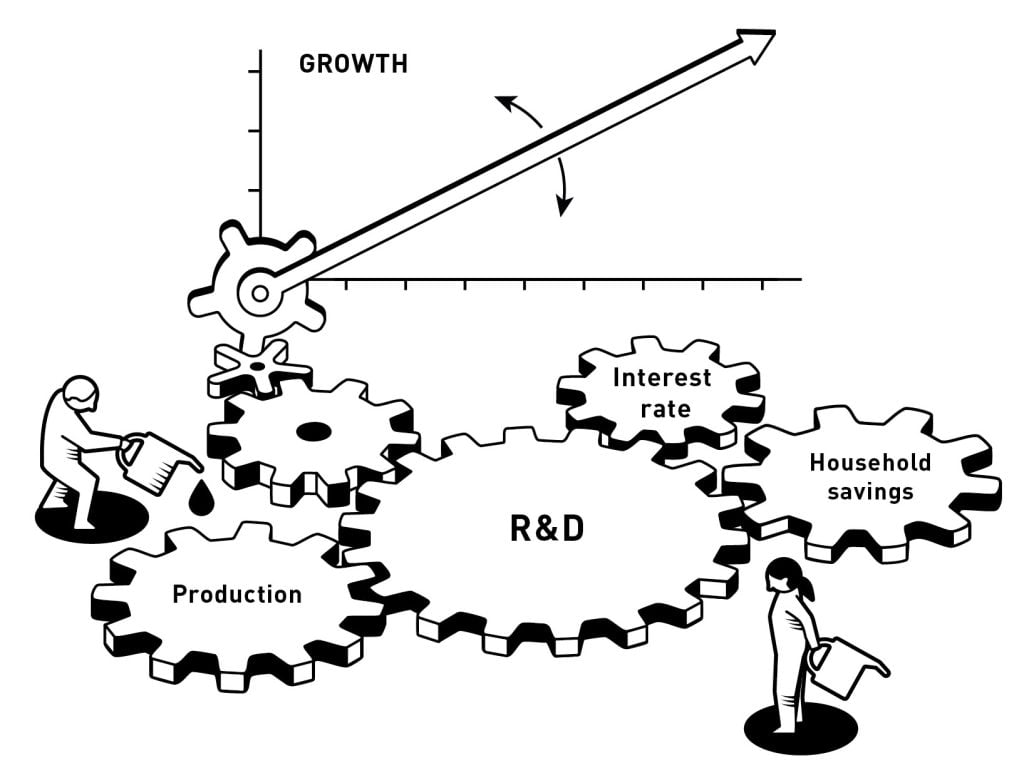

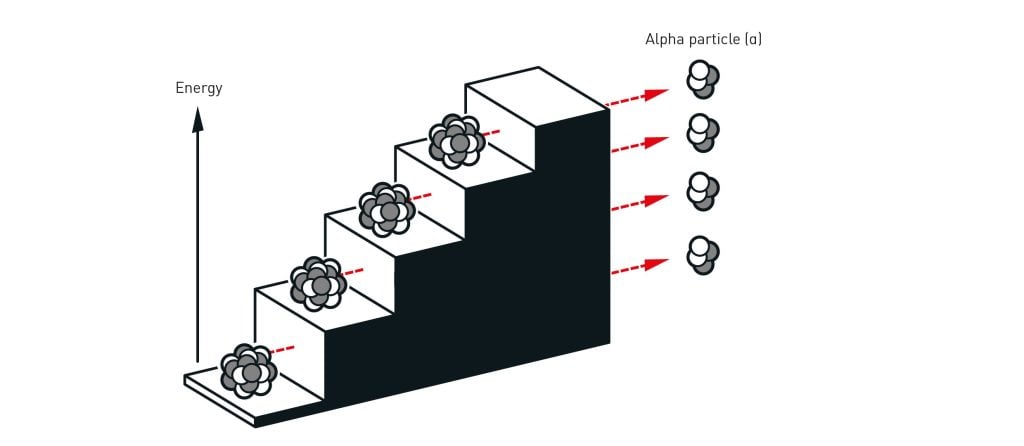

Aghion and Howitt realised that this transformative process of creative destruction, in which companies and jobs continually disappear and are replaced, is at the heart of the process that leads to sustained growth. A company that has an idea for a better product or a more efficient means of production can outcompete others to become the market leader. However, as soon as this happens, it creates an incentive for other companies to further improve the product or production method and so climb to the top of the ladder.

A simplified description of some of the model’s important mechanisms would be that an economy includes companies with the best and most advanced technology; when these take out patents on their products they can be paid more than their production costs and thus profit from a monopoly. These are the companies that have moved to the top of the ladder. A patent offers protection from competition, but not from another company making a new patentable innovation. If the new product or production process is good enough, it can outcompete the old one and further climb the ladder.

The potential to profit from a monopoly, even temporarily, creates incentives for companies to invest in research and development (R&D). The longer a company believes it can remain at the top of the ladder, the stronger the incentives, and the greater the investment in R&D. However, more R&D will lead to the average time to innovation decreasing, and the company at the top being pushed off the ladder. In the economy, a balance arises between these forces that decide how much is invested in R&D, thus also deciding the speed of creative destruction and economic growth.

Money for investment in R&D originates in households’ savings. How much they save depends on the interest rate which, in turn, is affected by the growth rate of the economy. Production, R&D, the financial markets and household savings are therefore linked and cannot be analysed in isolation. Economists call a model in which different markets are in balance a macroeconomic model that has general equilibrium. The model that Aghion and Howitt presented in their 1992 paper was the first macroeconomic model for creative destruction to have general equilibrium.

Aghion and Howitt’s model can be used to analyse whether there is an optimal volume of R&D, and thus economic growth, if the market has free reign and there is no political interference. Previous models, which did not analyse the economy as a whole, could not answer that question. It turned out that the answer was far from simple, because two mechanisms pull in different directions.

The first mechanism is based upon companies that invest in R&D understanding that their current profits from an innovation will not continue forever. Sooner or later, another company will launch a better product. From the perspective of society, however, the value of the old innovation does not disappear, because the new one builds upon the old knowledge. Outcompeted innovations thus have a greater value for society than for the companies that develop them, which makes the private incentives for R&D smaller than the gains to society as a whole. Society can therefore benefit from subsidising R&D.

The second mechanism looks at how, when one company succeeds in pushing another from the top of the ladder, the new company makes a profit while the old company’s profit disappears. The latter is often called “business stealing”, although it is of course not stealing in the legal sense. Therefore, even if the new innovation is only slightly better than the old one, profits may be significant and larger than the socioeconomic gains. Therefore, from a socioeconomic perspective, investments in R&D can be too large; technological development can be too rapid and growth too high. This creates arguments against society subsidising R&D.

Which of these two forces dominates depends on a range of factors, which vary from market to market and time to time. Aghion and Howitt’s theory is useful for the understanding of which measures will be most effective and the extent to which society needs to support R&D.

The model that Aghion and Howitt constructed in 1992 has led to new research, including the study of levels of market concentration, which involves the number of companies that compete with each other. The researchers’ theory shows that concentrations that are both too high and too low are bad for the innovation process. Despite promising advances in technology, growth has fallen in recent decades. One explanation for this, based on Aghion and Howitt’s model, is that some companies have become too dominant. More forceful policies that aim to counteract too much market dominance may be necessary.

Another important lesson is that innovation creates winners and losers. This not only applies to companies, but also to their employees. High growth requires a lot of creative destruction, which means that more jobs disappear and there is potentially high unemployment. Therefore, it is important to support people who are affected while making it easy for them to move to more productive workplaces. Protecting workers but not jobs, for example through a system that is sometimes called flexicurity, may be the right solution.

The laureates also demonstrate the importance of society creating conditions conducive to skilled innovators and entrepreneurs. Social mobility, where your profession is not decided by your parents’ identity, is thus important for growth.

Mokyr’s, Aghion’s and Howitt’s research helps us to understand contemporary trends and how we can deal with important problems. For example, Mokyr’s work shows that AI could reinforce the feedback between propositional and prescriptive knowledge, and increase the rate at which useful knowledge is accumulated.

It is apparent that, in the long run, sustained growth does not only have positive consequences for human wellbeing. First, sustained growth is not synonymous with sustainable growth. Innovations can have significant negative side effects. Mokyr argues that such negative effects sometimes initiate processes that uncover solutions to problems, making technological development a self-correcting process. Clearly, however, this often requires well-designed policies, such as in the areas of climate change, pollution, antibiotic resistance, increasing inequality and the unsustainable use of natural resources.

In conclusion, and perhaps most importantly, the laureates have taught us that sustained growth cannot be taken for granted. Economic stagnation, not growth, has been the norm for most of human history. Their work shows that we must be aware of, and counteract, threats to continued growth. These threats may come from a few companies being allowed to dominate the market, restrictions on academic freedom, expanding knowledge at regional rather than global levels, and blockades from potentially disadvantaged groups. If we fail to respond to these threats, the machine that has given us sustained growth, creative destruction, may cease working – and we would once again need to become accustomed to stagnation. We can avoid this if we heed the laureates’ vital insights.

Additional information on this year’s prizes, including a scientific background in English, is available on the website of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, www.kva.se, and at www.nobelprize.org, where you can watch video from the press conferences, the Nobel Prize lectures and more. Information on exhibitions and activities related to the Nobel Prizes and the prize in economic sciences is available at www.nobelprizemuseum.se.

“for having explained innovation-driven economic growth”

with one half to

JOEL MOKYR

Born 1946 in Leiden, the Netherlands. PhD 1974 from Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. Professor at Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA and Eitan Berglas School of Economics, Tel Aviv University, Israel.

“for having identified the prerequisites for sustained growth through technological progress”

and the other half jointly to

PHILIPPE AGHION

Born 1956 in Paris, France. PhD 1987 from Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Professor at Collège de France and INSEAD, Paris, France and The London School of Economics and Political Science, UK.

PETER HOWITT

Born 1946 in Canada. PhD 1973 from Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA. Professor at Brown University, Providence, RI, USA.

“for the theory of sustained growth through creative destruction”

Science Editors: Kerstin Enflo and John Hassler, members of the Committee for the Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel

Illustrations: Johan Jarnestad

Translation: Clare Barnes

Editor: Sara Rylander

© The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Nobel Prize lesson

Explore the free, readily available lesson on the economic sciences prize 2025 including videos, slideshows and more.

©Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

English

English (pdf)

Swedish

Swedish (pdf)

13 October 2025

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2025 to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt

“for having explained innovation-driven economic growth”

with one half to

Joel Mokyr

Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA, Eitan Berglas School of Economics, Tel Aviv University, Israel

“for having identified the prerequisites for sustained growth through technological progress”

and the other half jointly to

Philippe Aghion

Collège de France and INSEAD, Paris, France, The London School of Economics and Political Science, UK

Peter Howitt

Brown University, Providence, RI, USA

“for the theory of sustained growth through creative destruction”

Over the last two centuries, for the first time in history, the world has seen sustained economic growth. This has lifted vast numbers of people out of poverty and laid the foundation of our prosperity. This year’s laureates in economic sciences, Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, explain how innovation provides the impetus for further progress.

Technology advances rapidly and affects us all, with new products and production methods replacing old ones in a never-ending cycle. This is the basis for sustained economic growth, which results in a better standard of living, health and quality of life for people around the globe.

However, this was not always the case. Quite the opposite – stagnation was the norm throughout most of human history. Despite important discoveries now and again, which sometimes led to improved living conditions and higher incomes, growth always eventually levelled off.

Joel Mokyr used historical sources as one means to uncover the causes of sustained growth becoming the new normal. He demonstrated that if innovations are to succeed one another in a self-generating process, we not only need to know that something works, but we also need to have scientific explanations for why. The latter was often lacking prior to the industrial revolution, which made it difficult to build upon new discoveries and inventions. He also emphasised the importance of society being open to new ideas and allowing change.

Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt also studied the mechanisms behind sustained growth. In an article from 1992, they constructed a mathematical model for what is called creative destruction: when a new and better product enters the market, the companies selling the older products lose out. The innovation represents something new and is thus creative. However, it is also destructive, as the company whose technology becomes passé is outcompeted.

In different ways, the laureates show how creative destruction creates conflicts that must be managed in a constructive manner. Otherwise, innovation will be blocked by established companies and interest groups that risk being put at a disadvantage.

“The laureates’ work shows that economic growth cannot be taken for granted. We must uphold the mechanisms that underly creative destruction, so that we do not fall back into stagnation,” says John Hassler, Chair of the Committee for the prize in economic sciences.

The illustrations are free to use for non-commercial purposes. Attribute ”© Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences”

Illustration: Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2025

Illustration: Figure 1

Illustration: Figure 2

Illustration: Figure 3

Illustration: Figure 4

Illustration: Figure 5

Illustration: Figure 6

Popular science background: From stagnation to sustained growth (pdf)

Scientific background to the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2025 (pdf)

Joel Mokyr, born 1946 in Leiden, the Netherlands. PhD 1974 from Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. Professor at Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA and Eitan Berglas School of Economics, Tel Aviv University, Israel.

Philippe Aghion, born 1956 in Paris, France. PhD 1987 from Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Professor at Collège de France and INSEAD, Paris, France and The London School of Economics and Political Science, UK.

Peter Howitt, born 1946 in Canada. PhD 1973 from Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA. Professor at Brown University, Providence RI, USA.

Prize amount: 11 million Swedish kronor, with one half to Joel Mokyr and the other half jointly to Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt.

Further information: www.kva.se and www.nobelprize.org

Press contact: Eva Nevelius, Press Secretary, +46 70 878 67 63, [email protected]

Experts: Kerstin Enflo, +46 70 374 83 91, [email protected] and John Hassler, +46 70 811 72 63, [email protected], members of the Committee for the Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, founded in 1739, is an independent organisation whose overall objective is to promote the sciences and strengthen their influence in society. The Academy takes special responsibility for the natural sciences and mathematics, but endeavours to promote the exchange of ideas between various disciplines.

Nobel Prize® is a registered trademark of the Nobel Foundation.

Interview with the 2006 Nobel Prize laureates in physics, John C. Mather and George F. Smoot on 6 December 2006. The interviewer is Adam Smith, Editor-in-Chief of Nobelprize.org.

John Mather, George Smoot, welcome to Stockholm.

John Mather: Thank you.

George Smoot: Thank you very much.

When you very kindly spoke to me just after you had heard the news that you had been awarded the prize, George Smoot, you mentioned that you had 170 students in California who were expecting you to be there this week.

George Smoot: That’s correct. My superior and chairman at the department is teaching my lecture later today and my alarm already went off saying so to my lecture but there’s now a time difference, so she still has three more hours.

So the students have been understanding, do you think?

George Smoot: Yes, though they were disrupted by photographers and other things that went on.

Teaching is a very important part of your research career?

George Smoot: I see my job as both doing research and preparing the next generation. I like teaching. This semester I am teaching freshman physics, the second semester of freshman physics, it’s the thermophysics and electromagnetism. It’s a hard course for the students, but it is for all those who are going to become scientists years later.

Is it unusual for somebody at your level to continue to teach undergraduates?

George Smoot: It may be unusual, but the university requires us to teach, so unless you can pull the strings to teach upper division or graduate courses all the time – which some people do – your … will easily go between lower division which is the first and second year and the upper and graduate courses. I go between those.

Is undergraduate teaching a big part of your life as well?

John Mather: No, since I am a full time NASA employee my job is primarily to conceive and build new space projects. I do a lot of public speaking now, especially now since the prize announcement, but my main job is working on the project. In my case now is the James Webb Space Telescope, which is the successor planned for the Hubble Space Telescope. It would go up in 2013, so that’s my main job.

Do you pull graduate students into …

John Mather: We can, but we don’t usually, because it is hard for a student to compete with the professionals and get a thesis project from working on something that is being built. Mostly the graduate students work with missions that have already been launched.

It would be interesting to explore the difference between choosing students, graduate students to work on projects, and professionals to work on NASA projects. What do you look for when you look for those people?

George Smoot: It’s very different because with professionals on a big project like John’s project or the space project we are doing, you have to meet a deadline, you are meeting other people who are well trained and experienced are there and everyone has to work together as a team and meet the deadlines. With the students you are bringing them on because they show promise, and they need to learn and experience how to do science. It is very good to get them involved part time in a big project so they can learn about that later, but you have a small project that they are responsible for. If they get in trouble, you’ll have to bail them out in the big project. If they get in trouble on their own project, you can let them flounder until they find their way and it is very different. Right now I have five graduate students, one, … from Korea; one Daniels from Mexico; there’s two Americans, Mia Emm and Michelle Delinski who are Americans, and then I have one Italian student, Sarah … They are all doing different things, Sarah is working on the next generation cosmic background satellite, but she is working on how to separate the foregrounds from nearby galaxies’ signals from the distant signals.

So, microcosm of the international space center really.

George Smoot: For me there is sort of a sequence, you’re not only working in projects that are going on, the way that John is really focusing on, major projects, the James Webb is one of the biggest projects there is. I am sort of on intermedia projects, this Planck with European Space Agency and with some NASA … and I have also some other projects going on, so you have postdocs you’re training there, in the transition between being students and being fulltime researchers. Then graduate students and then I have undergraduates studying research projects with. I even take on high school teachers and students and so. We have an outreach thing which I would show you, just to explain the different paces of the universe. We have high school teachers and undergraduates involved and putting this together on the website, to make it available to high school students. It’s this pipeline where you start training them and until they eventually turn out to be in John’s area where they are doing the work.

You are looking for people who are just fully fledged, ready to go?

John Mather: Yes, we look also for young people that have promise and we hope to bring them in and let them learn the trade of space engineering and space science by working with people that have been doing it before, because there is a special discipline and knowledge about things that are very strange and things you would never think of worrying about for space missions. The fact that you can’t go and fix them ordinarily is a very special challenge for people because it is exactly the opposite of a graduate student project. On a graduate student project is working, you take data and publish your paper, and then you are on to the next one. With the space mission you get it working and then you have to make it work for quite a few months and before you trust it to send it up at the space where there is no hope of repair, usually, so it is a completely different discipline, but one well worth mastering because of the things that one can get only in space.

I imagine people have enormous self-confidence once they are ready for this.

John Mather: I don’t think so, I think we have to have accommodation of confidence and caution. The person who is too confident is dangerous and the person who has no ambition is dangerous. We have to have a mix of the things that are beyond what we can do but can still be proven. This is what we do.

From the perspective of the people who come to work for you, what do you think they look for from you, from your experience of your own scientific evolutions? What do you think makes a good mentor?

John Mather: I think that for me the people that have been mentored are the ones that have a creative process and have some knowledge of a wide variety of fields because the things that we have to do are usually spanning many disciplines. To get something to work in space you have to know a little bit of mechanical engineering, … engineering, electronic engineering, optical engineering, kinetic engineering, communications and to be sufficiently afraid of the environment out there to make sure that you think about all the things that could go wrong with your idea before you proceed. That is what I am looking for, people that have that combination.