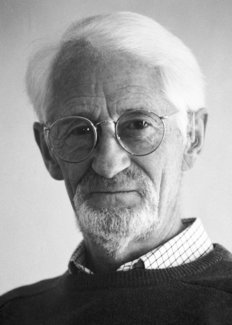

Jens C. Skou

Biographical

I was born on the 8th of October 1918 into a wealthy family in Lemvig, a town in the western part of Denmark. The town is nicely situated on a fjord, which runs across the country from the Kattegat in East to the North Sea in West. It is surrounded by hills, and is only 10 km, i.e. bicycling distance, from the North Sea, with its beautiful beaches and dunes. My father Magnus Martinus Skou together with his brother Peter Skou were timber and coal merchants.

We lived in a big beautiful house, had a nice summer house on the North Sea coast. We were four children, I was the oldest with a one year younger brother, a sister 4 years younger and another brother 7 years younger. The timber-yard was an excellent playground, so the elder of my brothers and I never missed friends to play with. School was a minor part of life.

When I was 12 years old my father died from pneumonia. His brother continued the business with my mother Ane-Margrethe Skou as passive partner, and gave her such conditions that there was no change in our economical situation. My mother, who was a tall handsome woman, never married again. She took care of us four children and besides this she was very active in the social life in town.

When I was 15, I went to a boarding school, a gymnasium (high school) in Haslev a small town on Zealand, for the last three years in school (student exam). There was no gymnasium in Lemvig.

Besides the 50-60 boys from the boarding section of the school there were about 400 day pupils. The school was situated in a big park, with two football fields, facilities for athletics, tennis courts and a hall for gymnastics and handball. There was a scout troop connected to the boarding section of the school. I had to spend a little more time preparing for school than I was used to. My favourites were the science subjects, especially mathematics. But there was plenty of time for sports activities and scouting, which I enjoyed. All the holidays, Christmas, Easter, summer and autumn I spent at home with my family.

After three years I got my exam, it was in 1937. I returned to Lemvig for the summer vacation, considering what to do next. I could not make up my mind, which worried my mother. I played tennis with a young man who studied medicine, and he convinced me that this would be a good choice. So, to my mother’s great relief, I told her at the end of August that I would study medicine, and started two days later at the University of Copenhagen.

The medical course was planned to take 7 years, 3 years for physics, chemistry, anatomy, biochemistry and physiology, and 4 years for the clinical subjects, and for pathology, forensic medicine, pharmacology and public health. I followed the plan and got my medical degree in the summer of 1944.

I was not especially interested in living in a big town. On the other hand it was a good experience for a limited number of years to live in, and get acquainted with the capital of the country, and to exploit its cultural offers. Art galleries, classical music and opera were my favourites.

For the first three years I spent the month between the semesters at home studying the different subjects. For the last 4 years the months between the semesters were used for practical courses in different hospital wards in Copenhagen.

It was with increasing anxiety that we witnessed to how the maniac dictator in Germany, just south of our border, changed Germany into a madhouse. Our anxiety did not become less after the outbreak of the war. In 1914 Denmark managed to stay out of the war, but this time, in April 1940 the Germans occupied the country. Many were ashamed that the Danish army were ordered by the government to surrender after only a short resistance. Considering what later happened in Holland, Belgium and France, it was clear that the Danish army had no possibility of stopping the German army.

The occupation naturally had a deep impact on life in Denmark in the following years, both from a material point of view, but also, what was much worse, we lost our freedom of speech. For the first years the situation was very peculiar. The Germans did not remove the Danish government, and the Danish government did not resign, but tried as far as it was possible to minimize the consequences of the occupation. The army was not disarmed, nor was the fleet. The Germans wanted to use Denmark as a food supplier, and therefore wanted as few problems as possible.

The majority of the population turned against the Germans, but with no access to weapons, and with a flat homogeneous country with no mountains or big woods to hide in, the possibility of active resistance was poor. So for the first years the resistance only manifested itself in a negative attitude to the Germans in the country, in complicating matters dealing with the Germans as far as possible, and in a number of illegal journals, keeping people informed about the situation, giving the information which was suppressed by the German censorship. There was no interference with the teaching of medicine.

The Germans armed the North Sea coast against an invasion from the allied forces. Access was forbidden and our summer house was occupied. My grandmother had died in 1939, and we four children inherited what would have been my father’s share. For some of the money my brother and I bought a yacht, and took up sailing, and this has since been an important part of my leisure time life. After the occupation the Germans had forbidden sailing in the Danish seas except on the fjord where Lemvig was situated, and another fjord in Zealand.

The resistance against the Germans increased as time went on, and sabotage slowly started. Weapons and ammunition for the resistance movement began to be dropped by English planes, and in August 1943 there were general strikes all over the country against the Germans with the demand that the Government stopped giving way to the Germans. The Government consequently resigned, the Germans took over, the Danish marine sank the fleet and the army was disarmed. An illegal Frihedsråd (the Danish Liberation Council) revealed itself, which from then on was what people listened to and took advice from.

Following this, the sabotage against railways and factories working for the Germans increased, and with this arrests and executions. One of our medical classmates was a German informer. We knew who he was, so we could take care. He was eventually liquidated by unknowns. We feared a reaction from Gestapo against the class, and stayed away from the teaching.

The Germans planned to arrest the Jews, but the date, the night between the first and second October 1943 was revealed by a high placed German. By help from many, many people the Jews were hidden. Of about 7000, the Germans caught 472, who were sent to Theresienstadt where 52 died. In the following weeks illegal routes were established across the sea, Øresund, to Sweden, and the Jews were during the nights brought to safety. From all sides of the Danish society there were strong protests against the Germans for this encroachment on fellow-countrymen.

In May and June 1944, we managed to get our exams. A number of our teachers had gone underground, but their job was taken over by others. We could not assemble to sign the Hippocratic oath, but had to come one by one at a place away from the University not known by others.

I returned to my home for the summer vacation. The Germans had taken over part of my mother’s house, and had used it for housing Danes working for the Germans. This was extremely unpleasant for my mother, but she would not leave her house and stayed. I addressed the local German commander, and managed to get him to move the “foreigners” from the house at least as long as we four children were home on holiday.

The Germans had forbidden sailing, but not rowing, so we bought a canoe and spent the holidays rowing on the fjord.

After the summer holidays I started my internship in a hospital in Hjørring in the northern part of the country. I first spent 6 months in the medical ward, and then 6 months in the surgical ward. I became very interested in surgery, not least because the assistant physician, next in charge after the senior surgeon, was very eager to teach me how to make smaller operations, like removing a diseased appendix. I soon discovered why. When we were on call together and we during the night got a patient with appendicitis, it happened–after we had started the operation–that he asked me to take over and left. He was then on his way to receive weapons and explosives which were dropped by English planes on a dropping field outside Hjørring. I found that this was more important than operating patients for appendicitis, but we had of course to take care of the patients in spite of a war going on. He was finally caught by the Gestapo, and sent to a concentration camp, fortunately not in Germany, but in the southern part of Denmark, where he survived and was released on the 5th of May 1945, when the Germans in Denmark surrendered.

I continued for another year in the surgical ward. It was here I became interested in the effect of local anaesthetics, and decided to use this as a subject for a thesis. Thereafter I got a position at the Orthopaedic Hospital in Aarhus as part of the education in surgery.

In 1947 I stopped clinical training, and got a position at the Institute for Medical Physiology at Aarhus University in order to write the planned doctoral thesis on the anaesthetic and toxic mechanism of action of local anaesthetics.

During my time in Hjørring I met a very beautiful probationer, Ellen Margrethe Nielsen, with whom I fell in love. I had become ill while I was on the medical ward, and spent some time in bed in the ward. I had a single room and a radio, so I invited her to come in the evening to listen to the English radio, which was strictly forbidden by the Germans – but was what everybody did.

After she had finished her education as a nurse in 1948, she came to Aarhus and we married. In 1950 we had a daughter, but unfortunately she had an inborn disease and died after 1 1/2 years. Even though this was very hard, it brought my wife and I closer together. In 1952, and in 1954 respectively we got two healthy daughters, Hanne and Karen.

The salary at the University was very low, so partly because of this but also because I was interested in using my education as a medical doctor, I took in 1949 an extra job as doctor on call one night a week. It furthermore had the advantage that I could get a permission to buy a car and to get a telephone. There were still after war restrictions on these items.

I was born in a milieu which politically was conservative. The job as a doctor on call changed my political attitude and I became a social democrat. I realized how important it is to have free medical care, free education with equal opportunities, and a welfare system which takes care of the weak, the handicapped, the old, and the unemployed, even if this means high taxes. Or as phrased by one of our philosophers, N.F.S. Grundtvig, “a society where few have too much, and fewer too little”.

We lived in a flat, so the car gave us new possibilities. We wanted to have a house, and my mother would give us the payment, but I was stubborn, and wanted to earn the money myself. In 1957 we bought a house with a nice garden in Risskov, a suburb to Aarhus not far away from the University.

I am a family man, I restricted my work at the Institute to 8 hours a day, from 8 to 4 or 9 to 5, worked concentratedly while I was there, went home and spent the rest of the day and the evening with my wife and children. All weekends and holidays, and 4 weeks summer holidays were spent with the family. In 1960 we bought an acre of land on a cliff facing the beach 45 minutes by car from Aarhus, and built a small summer house. From then on this became the centre for our leisure time life. We bought a dinghy and a rowing boat with outboard motor and I started to teach the children how to sail, and to fish with fishing rod and with net.

Later, when the girls grew older, we bought a yacht, the girls and I sailed in the Danish seas, and up along the west coast of Sweden. My wife easily gets seasick, but joined us on day tours. Later the girls took their friends on sail tours.

In wintertime the family skied as soon as there was snow. A friend of mine, Karl Ove Nielsen, a professor of physics, took me in the beginning of the 1960s at Easter time on an 8-day cross country ski tour through the high mountain area in Norway, Jotunheimen. We stayed overnight in the Norwegian Tourist Association’s huts on the trail, which were open during the Easter week. It was a wonderful experience, but also a tour where you had to take all safety precautions. It became for many years a tradition. Later the girls joined us, and they also took some of their friends. When the weather situation did not allow this tour, we spent a week in more peaceful surroundings either in Norway with cross-country skiing or in the Alps with slalom. We still do, now with the girls, their husbands and the grandchildren. Outside the sporting activities, I spend much time listening to classical music, and reading, first of all biographies.

When the children left home, one for studying medicine and the other architecture, my wife worked for several years as a nurse in a psychiatric hospital for children, then engaged herself in politics. She was elected for the County Council for the social democrats, and spent 12 years on the council, first of all working with health care problems. She was also elected to the county scientific ethical committee, which evaluates all research which involves human beings. Later she was elected co-chairman to the Danish Central Scientific Ethical Committee, which lay down the guidelines for the work on the local committees, and which is an appeal committee for the local committees as well as for the doctors. She has worked 17 years on the committees and has been lecturing nurses and doctors about ethical problems.

I had no scientific training when I started at the Institute of Physiology in 1947. It took me a good deal of time before I knew how to attack the problem I was interested in and get acquainted with this new type of work. The chairman, Professor Søren L. Ørskov was a very considerate person, extremely helpful, patient, and gave me the time necessary to find my feet. During the work I got so interested in doing scientific work that I decided to continue and give up surgery. The thesis was published as a book in Danish in 1954, and written up in 6 papers published in English. The work on the local anaesthetics, brought me as described in the following paper to the identification of the sodium-potassium pump, which is responsible for the active transport of sodium and potassium across the cell membrane. The paper was published in 1957. From then on my scientific interest shifted from the effect of local anaesthetics to active transport of cations.

In the 1940s and the first part of the 1950s, the amount of money allocated for research was small. Professor Ørskov, fell chronically ill. His illness developed slowly so he continued in his position, but I, as the oldest in the department after him, had partly to take over his job. This meant that besides teaching in the semesters I had to spend two months per year examining orally the students in physiology.

The identification of the sodium-potassium pump gave us contact to the outside scientific world. In 1961, I met R.W. Berliner at an international Pharmacology meeting in Stockholm. He mentioned the possibility of obtaining a grant from National Institutes of Health (NIH). I applied and got a grant for two years. The importance of this was not only the money, but that it showed interest in the work we were doing.

In 1963, Professor Ørskov resigned and I was appointed professor and chairman. In the late 1950s and especially in the 1960s, more money was allocated to the Universities, and also more positions. Due to the work with the sodium-potassium pump, it became possible to attract clever young people, and the institute staff in a few years increased from 4 to 20-25 scientists. This had also an effect on the teaching. I got a young doctor, Noe Næraa, who had expressed ideas about medical teaching, to accept a position at the Institute. He started to reorganise our old fashioned laboratory course, we got new modern equipment, and thereafter we also reorganised the teaching, made it problem-oriented with teaching in small classes. My scientific interest was membrane physiology, but I wanted also to find people who could cover other aspects of physiology, so we ended up with 5-6 groups who worked scientifically with different physiological subjects.

In 1972 we got a new statute for the Universities, which involved a democratization of the whole system. The chairman was no longer the professor (elected by the board of chairmen which made up the faculty), but he/she was now elected by all scientists and technicians in the Institute and could be anybody, scientist or technician. This was of course a great relief for me because I could get rid of all my administrative duties. A problem was, however, that I got elected as chairman, but later others took over. In the beginning it was very tedious to work with the system, not least because everybody thought that they should be asked and take part in every decision. Later we learned to hand over the responsibility to an elected board at the Institute.

In these years the money to the Institutes came from the Faculty, which got it from the University (which got it from the State). The money was then divided inside the institute by the chairman, and later by the elected board. It was usually sufficient to cover the daily expenses of the research. External funds were only for bigger equipment. Besides research-money we had a staff of very well trained laboratory assistants, whose positions–as well as the positions of the scientific staff–was paid by the University. The institute every year sent a budget for the coming year, to the faculty, who then sent a budget for the faculty to the University, and the University to the State.

This way of funding had the great advantage that there was not a steady pressure on the scientists for publication and for sending applications for external funds. It was a system that allowed everybody to start on his/her own project, independently, and test their ideas. Nobody was forced from lack of money to join a group which had money and work on their ideas. It was also a system which could be misused, by people who were not active scientifically. With an elected board it proved difficult to handle such a situation. Not least because the very active scientists tried to avoid being elected – i.e. it could be the least active who actually decided. In practice, however, the not very active scientists usually accepted to do an extra job with the teaching, thus relieving the very active scientists from part of the teaching burden.

In the 1980s this was changed, the money for science was transferred to centralized (state) funds, and had to be applied for by the individual scientist. Not an advantage from my point of view. Applications took a lot of time, it tempted a too fast publication, and to publish too short papers, and the evaluation process used a lot of manpower. It does not give time to become absorbed in a problem as the previous system.

My research interest was concentrated around the structure and function of the active transport system, the Na+,K+-ATPase. A number of very excellent clever young scientists worked on different sides of the subject, either their own choice or suggested by me. Each worked independent on his/her subject. Scientists who took part in the work on the Na+,K+-ATPase and who made important contributions to field were, P.L. Jørgensen (purification and structure), I. Klodos (phosphorylation), O. Hansen (effect of cardiac glycosides and vanadate), P. Ottolenghi (effect of lipids), J. Jensen (ligand binding), J. G. Nørby (phosphorylation, ligand binding, kinetics), L. Plesner (kinetics), M. Esmann (solubilization of the enzyme, molecular weight, ESR studies), T. Clausen (hormonal control), A.B. Maunsbach and E. Skriver from the Institute of Anatomy in collaboration with P.L. Jørgensen (electron microscopy and crystallization), and I. Plesner from the Department of Chemistry (enzyme kinetics and evaluation of models). We also had many visitors.

We got many contacts to scientists in different parts of the world, and I spent a good deal of time travelling giving lectures. In 1973 the first international meeting on the Na+,K+-ATPase was held in New York. The next was 5 years later in Århus, and thereafter every third year. The proceedings from these meetings have been a very valuable source of information about the development of the field.

My wife joined me on many of the tours and we got friends abroad. Apart from the scientific inspiration the travelling also gave many cultural experiences, symphony concerts, opera and ballet, visits to Cuzco and Machu Picchu in Peru, to Uxmal and Chichén Itzá on the Yucatan Peninsula, and to museums in many different countries. Not to speak of the architectural experiences from seeing many different parts of the world. And not least it gave us good friends.

It is not always easy to keep your papers in order when travelling. Sitting in the airport in Moscow in the 1960s waiting for departure to Khabarovsk in the eastern part of Siberia, we–three Danes on our way to a meeting in Tokyo–realized that we had forgotten our passports at the hotel in town. There were twenty minutes to departure and no way to get the passports in time. We asked Intourist what to do. There was only one boat connection a week from Nakhodka, where we should embark to Yokohama, so they suggested that we should go on, they would send the passports after us. I had once had a nightmare, that I should end my days in Siberia. When we after an overnight flight arrived in Khabarovsk we were met by a lady who asked if we were the gentlemen without passports. We could not deny, and she told us that they would not arrive until after we had left Khabarovsk by train to Nakhodka. But they would send them by plane to Vladivostok and from there by car to Nakhodka. To our question if we could leave Siberia without our passports the answer was no. When the train the following morning stopped in Nakhodka, a man came into the sleeping car and asked if we were the gentlemen without passports. To our “yes” he said “here you are”, and handed over the passports. Amazing. We had an uncomplicated boat trip to Yokohama.

It was not as easy some years later in Argentina. I had been at a meeting in Mendoza, had stopped in Cordoba on the way, had showed passport in and out of the airports without problems. Returning to Buenos Aires to leave for New York, the man at the counter told me that my passport had expired three months earlier, and according to rules I had to return direct to my home country. I argued that I was sure I could get into the U.S., but he would not give way. We discussed for half an hour. Finally shortly before departure he would let me go to New York if he could reserve a plane out of New York to Denmark immediately after my arrival. He did the reservation, put a label on my ticket with the time of departure, and by the second call for departure I rushed off, hearing him saying “You can always remove the label”. In New York, I stepped to the rear end of the line, hoping the man at the counter would be tired when it was my turn. He was not. I asked if I had to return to Denmark. “There is always a way out” was his answer, “No, go to the other counter, sign some papers, pay 5 dollars, and I let you in”.

In 1977, I was offered the chair of Biophysics at the medical faculty. It was a smaller department, with 7 positions for scientists, of which 5 were empty, which meant that we could get positions for I. Klodos and M. Esmann, who had fellowships. Besides J. G. Nørby and L. Plesner moved with us. The two members in the Institute, M. J. Mulvany and F. Cornelius became interested in the connection between pump activity and vasoconstriction, and reconstitution of the enzyme into liposomes, respectively, i.e. all in the institute worked on different sides of the same problem, the structure and function of the Na+,K+-ATPase. We got more space, less administration, and I was free of teaching obligations.

We all got along very well, lived in a relaxed atmosphere, inspiring and helping each other, cooperating, also with the Na+,K+-ATPase colleagues left in the Physiological Institute. And even if we all worked on different sides of the same problem, there were never problems of interfering in each others subjects, or about priority.

In 1988, I retired, kept my office, gave up systematic experimental work and started to work on kinetic models for the overall reaction of the pump on computer. For this I had to learn how to programme, quite interesting, and amazing what you can do with a computer from the point of view of handling even complicated models. And even if my working hours are fewer, being free of all obligations, the time I spent on scientific problems are about the same as before my retirement.

I enjoy no longer having a meeting calendar, I enjoy to go fly-fishing when the weather is right, and enjoy spending a lot of time with my grandchildren.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Jens C. Skou died on 28 May 2018.

For more updated biographical information, see:

Jens Chr. Skou: Lucky Choices. The Story of my Life in Science. U Press, Copenhagen 2016.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

See them all presented here.