Bengt Holmström

Biographical

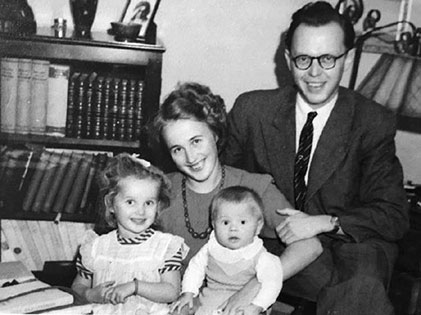

I was born in Helsinki in 1949. My sister Marianne was born in 1946. Our parents were married when the war against the Soviet Union ended in 1944. My father had spent five years on the front like so many young Finnish men. The post-war years were challenging socially and economically. The government had to arrange homes for over 400,000 refugees from regions lost in the war. In addition, Finland had to pay onerous reparation fees. Despite these hardships, I remember my early childhood as a happy time. There were plenty of children around to play with. We entertained ourselves with games of all sorts. There were few toys but our imagination more than filled the void. It taught me that material wealth is not essential for happiness.

Finland is a bi-lingual country. My father belonged to the Swedish speaking minority and Swedish became my mother tongue – a misnomer, because my mother had spoken Russian, German, Finnish, but hardly any Swedish in her home. Her mother was Estonian and her father, born in St Petersburgh, was of Baltic and Mediterranean origin. My mother, still alive and alert at 92, went to work when she was fifteen to ease the financial burden of her family, spending most of her career at her brother-in-law’s law firm. Pragmatic, principled and when necessary demanding, she was the bedrock of the family. Her unconditional love gave me a sense of security and the belief that life would turn out well whatever I decided to do.

My father got an MBA after the war and served in various executive positions in the shipping industry throughout his career. Had it been financially possible, he would most likely have become an academic. He was a renaissance man, with a big and varied library. It included a copy of Paul Samuelson‘s Economics text, which he referred to when he needed to justify spending on something that wasn’t necessary (he was supporting the Finnish economy.) He mastered six languages, including Italian and Latin. He was fascinated by American literature and politics and subscribed to Time Magazine to keep himself informed. Our dinner conversations were wide-ranging and animated. My mother recalls that I asked a lot of “stupid” questions; my sister remembers that I would not easily give up my point of view. But we rarely ended up angry at each other. I’m very grateful for the open, multicultural atmosphere that prevailed in our home.

My early education

I learned basic arithmetics and reading early and therefore started elementary school a year ahead of schedule at age six. I failed my physical examination, because I couldn’t reach my left ear with my right hand going over the head – a basic test of physical maturity. But my mother’s persistent pleas got me past this potential hurdle. The consequence was that I was always the youngest student in class and for a long time also the smallest. It didn’t bother me at the time, but in retrospect it may have contributed to my focus on school work at the expense of learning social skills by interacting more with my class mates.

I went to a private, Swedish-speaking middle/high school (Munksnäs svenska samskola) and got a very good education. I liked school, because I was curious and did well in most subjects, especially mathematics. At the end of high school there was a nation-wide matriculation exam that the Ministry of Education administered each spring. The exam covered four mandatory topics and up to two elective ones. The answers were graded by independent examiners, which made this a test not just for the students, but also the teachers and the school. As one of the top students in my class I was expected to pass with flying colors, but I failed essay-writing and had to retake that part in the fall. This was a major embarrassment, but I wasn’t entirely surprised. Writing had been a challenge for me throughout high school; I was slow and often needed extra time. I wrote about the causes of over-fishing (we were given ten titles to choose from) without knowing much about the empirical facts. I recall being pleased with my theoretical arguments, but speculative theories were not what the examiners were looking for.

Luckily, I met my future wife Anneli (née Kuusakoski,) soon after failing the exam. Rather than brooding over this I spent a wonderful, fun-filled summer together with her. In the fall I passed the essay exam without much difficulty.

Undergraduate studies

Because I didn’t graduate in the spring I couldn’t apply to the Helsinki University of Technology and become an engineer as I had hoped. Instead, I ended up studying mathematics, physics and statistics at the University of Helsinki, which accepted students without an entrance exam if they had passed with distinction the mathematics part of the matriculation exam.

The years at the University of Helsinki were enjoyable and edifying. The mathematics and statistics departments were excellent with some fine teachers. Seppo Mustonen in statistics was a highly original, creative professor, who viewed the domain of statistics broadly and made many practically and important contributions. Olli Lokki was another professor I greatly admired. His course in applied mathematics introduced me to operations research and game theory. These were topics that were novel, exciting and offered good prospects for a non-academic job. I wrote my master’s thesis with him: a non-linear programming algorithm applied to quality control. Neither Lokki nor Mustonen were pedagogical stars – far from it – but their lectures were eclectic, inspiring and delivered with passion. They taught me the importance of putting your soul into teaching.

Undergraduate studies at the university were rather unstructured in those days. There were degree requirements, of course, but no one really monitored student progress. One did not have to attend classes to take exams. Exams were offered multiple times a year in all subjects and there was no limit on the number of times one could retake exams if one failed. With such weak incentives, the average time to graduation was long and many failed to finish their degree.

Socially, life at the university was engaging. The student rebellions were in full swing across the Western world and had just reached Finland by the time I entered. Established views were being questioned, debated and protested against. Normally I don’t like to go with the crowd, but I did participate in the occupation of the Old Student House in Helsinki – an enduring legacy of the student protests. The rebellions led to profound changes in the governance of universities, adding student and staff representation to the traditional academic boards of governance. Today I think most of these decisions were misguided and I have been actively engaged in trying to undo some of the damage.

Ahlström

After graduating in the spring 1972 Anneli and I got married. I began working as an operations research analyst at Ahlström, one of the ten largest firms in Finland at the time. It was a family controlled conglomerate with around 30 factories, a few of them outside Finland. Ahlström had embraced the use of computers early. Under the leadership of Jarl Engblom, the CFO, the firm had developed a large-scale linear programming model to aid management with its long-term strategic planning process. I was hired to fine-tune the model and collect the data to implement it. It was a great way to learn how Ahlström functioned and how the financial system was structured.

But it did not take many trips to the factories to realize that the project was going to be very difficult to implement. Linear programs ask for data that firms do not routinely collect, making the input unreliable. More importantly, the factory bosses were suspicious of a model that would influence how headquarters would distribute funds for investments and other shared resources. It was apparent that they were trying to figure out how to game the model to fund projects they were convinced were right for their factory. After some months of data collection I became convinced that the quality of the data was so poor that we could not trust the model and therefore we should stop the project. This was not welcome news for the CFO, but he understood and reluctantly accepted my judgment. (As it turns out, large-scale corporate planning models, so popular at the time, went soon out of fashion.)

As a substitute, I began working on smaller models to serve the factories rather than the headquarters. This was more successful for two reasons. It alleviated the incentive to distort information, because now the factories were in charge. The second reason was that I used the model in a way an economist might use it – initially as a descriptive rather than prescriptive device. If the model’s answer did not align with what they were doing I explained how the model was reasoning and asked what it was missing. That built trust. Through a process of feedback and adjustments I would eventually get sufficiently close to their production plan so that we could discuss whether their resources could be used better. The human mind is very bad at figuring out the opportunity cost of resources. With simple linear programs, I could describe the logic behind the model’s thinking in a way that the managers understood and appreciated.

My two years at Ahlström led to and influenced my academic research on incentives and organizational design. I have drawn on my work experience when judging the relevance of models and several of them, for instance on career concerns, were directly inspired by what I saw at Ahlström. I was very lucky to be given the chance to work with a fantastic CFO at such a young age.

Stanford

Towards the end of my second year at Ahlström I won an ASLA-Fulbright grant to enroll in the Master’s program in operations research at Stanford University. I left for California in September 1974 and was joined one month later by Anneli and our newborn son, Sam. Soon after arriving I began to think about doctoral studies either in the Operations Research Department or in the Graduate School of Business. I enrolled in a couple of doctoral classes to see if I could handle the material and to get a reference for my applications. I was thrilled when I heard that I had been accepted into the Decision Sciences program at the GSB, formally starting in the fall 1975, but de facto transitioning into it right away.

Studying at Stanford was so different from what I was used to in Finland. The course load was much heavier and the pace much faster. I realized I could have finished my undergraduate studies in two rather than four years. I was also amazed by the interaction between students and teachers in class and outside.

In the math department, Karel deLeeuw taught functional analysis using the Socratic Method. He assigned readings in advance and spent the entire class time discussing illustrative examples and issues. Typically, he would pose a problem and let us figure out how to approach and solve it. He knew full well whether an approach would be successful or not, but he would never tell us and simply nudge us along if we got stuck. Walking down wrong paths was an essential part of the exercise. It was a masterly, engaging performance and a wonderful way of learning.

In the operations research department George Dantzig’s class on linear programming was equally memorable. As the father of the subject, he told stories about how he discovered the simplex algorithm, including the many dead-ends he had tried out in search of a faster method. Context and stories were an integral part of his teaching. In the final exam I got full credit for a proof that was incomplete. In the margin he had written “Had God been just, your method would have worked!!” For him the journey was more important than reaching the destination.

At the GSB Bob Wilson was a towering figure. Not yet 40 years old – and looking ten years younger – Bob’s influence extended well beyond the Decision Sciences group. The first economics class I attended was Bob’s iconic Multi-Person Decision Theory course. It was comprised of new papers on various topics that Bob thought were interesting. Each year was different (I took the class three times). Bob’s teaching style made a lasting impression on me. He didn’t spend time on criticizing the papers or going through them in detail. Instead he focused on why the question posed in a paper was interesting and how that problem was transformed into an economically relevant, mathematically tractable model. “Formulation is 90% of the analysis,” he used to say. It took me a long time to fully appreciate the significance of this message.

Early in the class I asked Bob what I should read if I wanted to understand incentive problems of the sort I had encountered at Ahlström. Bob suggested that I look at Groves’ recent paper on incentives in teams.* I read it immediately but found it disappointing. With my operations research background, the model looked hopelessly unrealistic. I did not understand that the art of modeling is to figure out what can be left out of a model without losing relevance, not what can be fit in and still solve it (paraphrasing Mike Rothschild’s insightful words to me). Eventually I came to appreciate the economic approach, but not before I had wasted a semester working on a potential thesis on integer programming. Bob’s informal reading group was of much help. The regulars were my fellow students (and life-long friends) Takao Kobayashi and Froystein Gjesdal, who worked on incentive problems; William Thomson, who worked on social choice problems; and Roger Noll, Barry Weingast and Linda Cohen who were visiting political scientists from Cal Tech. The meetings had no set structure or readings. Whoever had something to say would go to the black board and sketch a model, discuss a problem or just bring up an interesting issue worth thinking about. It was part fun, part scary, and always inspiring.

As an advisor, Bob was extremely generous with his time. He liked to put his students on a regular schedule: discipline was essential for good work (something that regrettably hasn’t stuck with me). In the beginning I met Bob weekly.

It was a great incentive scheme. I didn’t dare to go to his office empty-handed and usually managed to produce something at the last minute. Bob rarely expressed strong views on what I presented (as he put it, ideas were like delicate plants that one should not step on), but I learned to read his delicate signs of approval or disapproval. His comments were deep and penetrating and his ability to see the connections between my results and earlier work were invaluable. Just as importantly, his vision of where the field was headed and what role incentive and information theories would play in economics were an inspiration for his students. It’s no exaggeration to say that the use of modern game theory would not be what it is today without the foresight and insight that Bob provided for a several generations of young scholars around the world.

There were many other professors I benefitted from at Stanford. At the GSB Joel Demski enriched my understanding of agency theory and through its connections to accounting. Dave Kreps and Mike Harrison, who were the young stars in Decision Sciences, taught a lovely course on diffusion processes. Dave was on my thesis committee and has continued to offer me advice throughout much of my career.

Stanford provided an exceptional education. My only regret is that I rushed through my studies in three years, which was possible, because there were few course requirements (as I recall, the main requirement was to take five or six MBA courses!). There would have been much more economics to learn. Fortunately, I’ve had the opportunity to return to Stanford many times to draw on the insights and inspiration from my teachers, colleagues and friends there. It remains my intellectual home.

Returning to Europe

The rules for the Fulbright stipend required that I leave the U.S. after completing my degree. So I didn’t go on the regular job market, but instead took a one-year post-doc position at the Belgian research center CORE in 1977–78. The intellectual atmosphere was stimulating under the exemplary leadership of Jacques Dreze, and academically the visit was a success. For Anneli and Sam it was a challenging year, because CORE had just moved to Louvain-la-Neuve before we arrived and none of us spoke French. But the Belgian food never failed to lift her spirits.

I got a junior faculty position at the Hanken School of Economics for the following academic year.** It was nice to be back in Finland with family and friends, but academically the bureaucracy was stifling. Without the company of Björn Wahlroos, who left academia early for a stellar career in banking (currently the Chairman of Nordea), it would have been much worse. We became good friends and I have continued to benefit from his valuable insights and feedback especially on the relevance of my work on liquidity.

Around Christmas I got a letter from Steve Shavell, asking me whether I would consider returning to the U.S. and if so, would I be interested in Harvard? To my surprise Anneli was ready to return (for a year or two, she would be quick to add). In the end Harvard decided not to invite me to talk, but CarnegieMellon, Northwestern and Yale did. My first talk, at Yale, went poorly, but the visit was saved by Steve Ross, who dispelled my disappointment with charm and humor. We became immediate friends. Thanks to him, the two other talks went much better and in the end I got job offers from all three places.

Meds and Northwestern

I chose Northwestern. My parents wondered whether I knew what I was doing; Yale had such a superior reputation in Europe. But MEDS had the talent I was looking for. The department had hired an exceptional group of applied game theorists including Ehud Kalai, John Roberts, Mark Satterthwaite, Roger Myerson, Nancy Stokey and Paul Milgrom. The excitement in the department was palpable. Dean Jacobs, who I saw right after my seminar, sealed the decision by offering me a job on the spot.

My four years at MEDS – which now feel more like a decade – were wonderful both academically and socially. As befits junior faculty, we were competitive and worked very hard to outperform each other. But we also greatly appreciated each other’s work. We exhibited a peculiar mix of insecurity about our tenure prospects at the same time as we felt very excited about our research. It was a time with an abundance of problems to solve and ideas to pursue and things to talk about day in and day out. With Roger Myerson I spent endless hours thinking about the right definition of efficiency under asymmetric equilibrium. It was (and remains) a slippery problem that we were lucky to get some closure on. With Milt Harris, who joined the finance department a bit later, I studied wage dynamics. Milt’s style of working was a revelation. We would sit and do everything together, including writing the paper. It was both productive and fun. Much credit for the MEDS magic goes to the “elders” that provided adult supervision: Stan Reiter, Mort Kamien, Nancy Schwartz and David Baron. Mort used to walk around the department to see how we youngsters were doing. Once he came in when I was in an especially sour mood over my poor teaching. He suggested I go to the board and present the lecture I just had given. I had barely begun the mock lecture when he interrupted me: “That’s your problem.” “You said ‘this is easy’. Never say something is easy. It makes the students nervous that they may not get it. And if they get it, there is no bonus, because you said it is easy. Say nothing, or say that it is difficult. Then there is only upside for the students.” This remains the most memorable and possibly the most valuable advice I’ve ever gotten about teaching. Mort was a wise and generous colleague and mentor.

There was an additional bonus from being at Northwestern – it’s proximity to the University of Chicago. I visited the economics department in the winter quarter 1981. The visit opened my eyes to the power of the Chicago school of economics as exemplified by Becker‘s, Rosen’s and (a little later on) Coase‘s work. At MEDS we mainly discussed game theory and information economics – how to formulate and solve technically demanding problems. It was a natural continuation of what I had learned at Stanford. I found the positive approach to economics that permeated Chicago very appealing. After my visit I often went down to Chicago to participate in and give seminars. I liked the aggressive give and take, because it was stimulating and done in earnest.

Yale SOM

The MEDS department began to lose people in my third and fourth year there. First John Roberts and then Dave Baron moved to Stanford. Both were instrumental to the MEDS success. When Paul Milgrom visited Yale SOM and decided to stay there, I was ready to leave. I worried (prematurely as it turns out) that MEDS would lose its magic. When Yale made me a tenured offer I accepted it.

Paul and Steve Ross were the biggest reasons for moving to Yale. Steve was the intellectual leader. He was very accessible and frequently held court in his office for whoever happened to drop by, dazzling us with his lightning quick mind. Paul’s brilliance I knew from Northwestern. We had talked almost daily, often walking to or from the office together. But we had never cooperated on a project. I hoped that we would hit on something interesting once we were in a quieter place.

We did indeed. I had been bothered by the fact that the models we had used to characterize optimal incentive contracts, produced unrealistically complicated answers. These models could not explain the wide-spread use of simple piece rates, for instance. Soon after arriving at Yale, I went to discuss this issue with Paul. In a single, intense session we sketched out a bare-bones model, based on the intuition that linear contracts provide robust incentives. The model was meant to be a first stab at explaining piece rates, but proved far more interesting than we ever imagined. The model was very tractable and soon took us in a number of different directions.

The most important, and unexpected, payoff came when we realized how important it is to study multitasking – the case where employees work on several tasks simultaneously and have to decide how they allocate their time between these tasks. If some tasks are easy to measure (such as output produced) while other tasks are hard to measure (such as quality of the output), then muting the incentives for the easy-to-measure task is an indirect way to provide incentives for the hard-to-measure task. Multitasking can explain why firms so commonly use low-powered (or no) explicit pay-for-performance incentives. It also leads to the insight that job design, bureaucracy and promotions are potent, cheaper incentive instruments within firms. Our quest for understanding simple piece rates led us to a much broader, richer theory of incentives, in which piece rates play a limited role.

Needless to say, without Paul I would not be writing this essay. The exhilaration we felt when we worked on the sequence of papers described briefly above, and in more detail in my prize lecture, is hard to put in words.

MIT

We loved living in Guilford, in a modest house near the water. Seeing and walking along Long Island Sound every day was precious. But after eleven years at Yale and Sam gone to college we were ready to move to MIT in 1994.

It was the first time that my primary appointment was in an Economics department rather than a business school. The first thing I noticed was how harmonious the department was. Differences in opinion were vented vigorously at times, but people did not hold grudges and there was a shared sense of responsibility for maintaining the excellence of MIT Economics. That’s how it still is today after a successful generational transition. The level of excitement among our stellar, young faculty is at least as palpable as it was at MEDS, but broader as it reflects the rapidly progressing frontier of all empirical work. It tells a lot about the MIT culture that the shift from theory to empirical research has gone so smoothly and successfully.

Moving to MIT gave me the opportunity to work more closely with Jean Tirole, who visits MIT six weeks of the year. We had begun a project on financial crises after my sabbatical in Finland in 1991–92, when the Nordic countries, and especially Finland, were hit by severe recessions due to collapses in their banking systems. We wrote a string of papers focused on the demand for insurance (liquidity) and the resulting scarcity of collateral. At the time, people seemed skeptical about collateral shortages, but today the shortage of “safe assets” and the role of government supply of safe assets are vibrant research topics.

In 2008 I was invited to the yearly central bank conference in Jackson Hole to discuss an inspiring paper by Gary Gorton entitled “The Panic of 2007.” This led to a second line of research on financial crises, focusing on the role of debt in money markets. Together with Gary and TriVi Dang I have studied the optimality of information-insensitive debt in the production of private money by banks. The project has been very exciting, partly because it is controversial. Our work suggests that opacity in money markets is a logical consequence of optimal contracting. This contrasts with the widely held view that transparency is essential in money markets and for the credibility of the banking system. The issue is still unsettled, but I think our point of view has won more support over the years.

My work on financial crises led to a deeper interest in policy issues. MIT, with its broad footprint and strong network of alumni has given me ample opportunities to connect with policy makers and central bankers. MIT’s reputation as the leading university of technology also gave me the opportunity to spend thirteen interesting, edifying years on the board of Nokia. I got an inside look into corporate governance, which was intellectually interesting and valuable for my work with Steve Kaplan. Nokia also provided a unique window into the rapidly changing world of ICT and most interestingly perhaps, what the young people around the world are thinking and feeling. The entrepreneurial spirit and activities at MIT continue to be the perfect springboard for keeping abreast with new technological trends and how they will impact organizations.

I have had the pleasure to make close friends in the community of economists and scientists at MIT and Harvard. The list is too long to include here, but I want to single out Oliver Hart, my closest intellectual partner and close friend throughout these years. We have debated approaches to contracts and organizations ad infinitum. We have written a few papers as a result. But more important than the papers, is the special friendship and trust that has developed between us. Without Oliver, my time in Cambridge would have been much less rewarding.

Let me close with a story about Paul Samuelson, which epitomizes his spirit and thereby the spirit of MIT. Occasionally he would invite me on Friday afternoons to share a glass of sherry in his office, which was next door to mine (I trust that this won’t get me into trouble). Talking to Paul was always inspiring. One Friday when I went for another edifying chat, I was met by a sharp question: “Do you ever change your mind?” I didn’t know where he was going with the question, but it sounded ominous. I hedged my answer with a sheepish “sometimes,” whereupon he proceeded to remind me of a conversation we had had about executive pay shortly after I arrived to MIT. I had defended the use of incentive options based on my work with Steve Kaplan and he had accepted my argument (sort of), noting that “it’s never too late to learn something new.” But the financial crisis had made him furious at the banking executives and their over-sized bonuses, which in his view had played a key part in the catastrophe. He wanted to know if I was ready to acknowledge that I had been wrong fifteen years ago. I had changed my mind, but the message of the story is the exceptional passion and memory of Paul at 94, still fully engaged with the political and economic issues of the day.

Gratitude

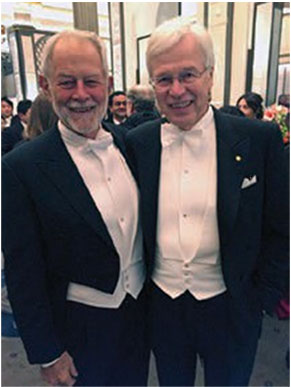

I feel extremely fortunate to have had the opportunity to interact with brilliant economists like Paul Samuelson, Ken Arrow, Bob Aumann, Bob Wilson, Peter Diamond and many of MIT’s brilliant young minds. I am deeply honored and grateful to the Royal Academy for bestowing me with this prize and for making the week in Stockholm so memorable for me and my family.

To my wife Anneli and my son Sam: Thank you for your love and support. You have shared the pain and you deserve to share the gain from the award.

* Groves T. “Incentives in Teams.” Econometrica, July 1973.

** The name of the school at the time was the Swedish School of Economics and Business; the education was in Swedish and primarily served the Swedish speaking minority in Finland.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.