Olga Tokarczuk

Biographical

I’d like to write this autobiographical sketch in a concise, chronological way, based on the reliable passage of time and its usual markers – the years. Then I would see my life as a linear process, gradually accumulating knowledge and experience, even leading towards a goal of some kind. Or at least aiming for one. An alternative version of this approach would be a CV listing the places where I was educated and the academic results achieved. But I realised that if I had to approach my 58-year-old life in that way I’d never write more than a single page.

I have always held that writers don’t really have biographies, and that the best way to find out about them is to read their books. The reason why they don’t have biographies is not because nothing interesting ever happens in their lives, or because they’re people of a special kind whose lives take a different route from everybody else’s, but because writing takes up too much of a person’s inner time, and so in many cases there isn’t enough of it left for other activities. Attention that is focused on the inside doesn’t go hand in hand with a good memory, as Nabokov pointed out. Writers don’t have biographies because their minds are used to inventing stories, making them up, fictionalising and at the same time neglecting things that are real. And, seen from the outside, their lives are bound to look boring, just sitting at a desk for hours, sometimes days on end. If I were to write my autobiography honestly, I’d have to include the life stories of characters from my books, and the life stories described in them are part of me as well.

So in this short autobiographical sketch I shall focus instead on my own development and inquiries, trusting a memory that in my case is very capricious. I don’t know why, but I can’t remember any of the “major” events, such as my first day at primary school, my sister’s birth when I was five, or moving house; I do have a foggy memory of my high-school graduation exams, but defending my master’s thesis has gone clean out of my head. I can’t remember being accepted for university or receiving my college diploma.

But I well remember a freezing winter afternoon, for instance, when dusk was already falling, I was taking off my skates under a large sky that was just switching on its stars, and when the steam coming out of my mouth formed speech bubbles, it made me feel like a character in a cosmic cartoon.

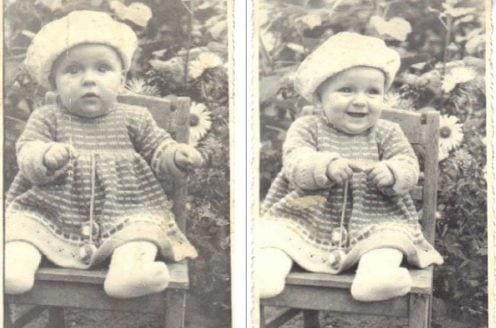

And I remember when this picture was taken.

I know what I was thinking – I wanted to express as clearly as I could that it’s better to be together than apart – an extremely important discovery at that age, when we’re desperately afraid of being separated from what we love. Later on, I made it into a general belief that has been with me throughout my creative life – that our task is to synthesise and consolidate the world, looking for connections, both overt and hidden, and building an image of the world as a complex whole full of mutual relations.

I was the first of two children born to a pair of teachers, who as a young married couple full of energy and enthusiasm came to the so-called Recovered Territories (the part of western Poland that before the Second World War belonged to the German Reich, but was assigned to Poland after it under the terms of the treaty signed at Yalta as compensation for the territory it had lost to the east, which is now part of Ukraine). My parents had a strong social commitment, and threw themselves into their work at the people’s university, which educated young people from the countryside and small towns. The school, grandly named “The People’s University”, was located in a beautiful old hunting manor adapted to suit its needs. It was on the edge of the village, behind some fish ponds, on a flood plain near the river Oder, which meant that on a fairly regular basis the river overflowed, coming all the way to the park, and throughout my life I’ve had dreams about floods. The park was large and old, and there was an oak forest and the marshes of the Old Oder, meandering channels separated from the main course of the river, as exotic and mysterious as the drainage basin of the Amazon. To this day, the fickle Oder is one of Europe’s few remaining wild rivers.

Figure 1.

Recently I read somewhere that in the first few decades of our lives our tissues, and in particular our bones and teeth, absorb from the surrounding environment a unique cocktail of chemical elements typical of the given place. For this reason, after hundreds and thousands of years, archaeologists can tell where a person was from, where he grew up. I’m sure that in my case they’ll be able to recognise the unique mixture exclusive to that place – of a big, flat space by a river, poor, sandy soil and the large oak woods and pine forests of the Oder drainage basin, all of which, transformed into chemistry, have recorded themselves in my body. I think that should be an important inducement for reflection on one’s own identity. Maybe in a topsy-turvy world we should take this into consideration too – we live in the drainage basins of rivers, and as creatures who consist of water to a very large degree, we belong to those rivers. So my first identity is as a “daughter of the Oder”.

From today’s perspective, many people might see the 1960s as ancient history. It really was another world. In Poland there was no public television yet. I remember watching a television programme for the first time at the age of six. So I can say that I belong to a generation of people who were not shaped by television from early childhood. Telephones were rare, and were operated by turning a crank handle. You placed a call to the number you wanted via the exchange, and waited for your connection. There were hardly any private cars, which meant that every single journey, even a trip to the nearest town, was a major expedition. We lived on a rather unvaried diet of locally produced food. I had no idea what a banana tasted like. Lemons were a luxury.

I was an untroublesome child who looked after herself. For a short time I went to the village kindergarten, but I didn’t feel too good there. My strongest memory of the place is of being made to have a lie-down in the middle of the day and of sitting in a tree when I didn’t want to play with the other children. But I did have a lot of freedom, which these days would be unimaginable. I used to spend a lot of time at the University with my parents, the teachers and pupils. I used to go to the lessons my parents taught, and I took part in everything that went on at the school – choir practice and dance group rehearsals, stage shows, outings, evening assemblies, both the entertainments and the work. Now I think the freedom I had as a child was a great gift that made me into someone who’s curious about everything, constantly in search of something. That said, I also love being on my own, and have always felt all right in my own company.

I think the only word I can use to describe my fondness for exploring is vagrancy. Before I ever went to school I used to spend a great deal of time on walks, investigating the enormous park, its ponds, paths, hidden nooks and passages; I also used to go to the nearby village to observe the people, their way of life, the objects they had and their animals. I used to head off to the banks of the Oder too; instinctively aware of its power and danger, I always kept my distance from its unpredictable current. This childhood vagrancy has stayed with me all my life, and whenever I find myself in a new place, I like to have a reconnoitre, to get to know the short-cuts, the relative location of the buildings and the major landmarks. I also think the best way to explore a city is to set off on an unplanned walk, letting pure whim and fancy be your guide as you wander the streets. As an adult traveller I have spent days at a time touring great cities in this way – London, Moscow and New York – in comfortable shoes and with a thermos in my backpack, walking the length and breadth of the place, and only using the subway as a last resort.

I taught myself to read, I’m not sure exactly when, as if it were something as natural as walking. I have often wondered whether the ability to read is built into our brains as a potential skill, or whether perhaps we inherit it from our ancestors who learned to read during their lives, in which instance I suspect it would only go a few generations back. In my case this ability was definitely to do with the fact that I was brought up among books – my dad ran the school library, and I dug around in them from early childhood. They weren’t books for children at all. One of my favourite early books was a collection of partisan songs. I knew how to sing them, so reading with understanding came to me naturally and easily. Among the hundreds of volumes eagerly borrowed by the pupils there were also art books and encyclopaedias. I can boldly say that encyclopaedias were my favourite literary genre throughout my childhood – my first “constellation” reading matter.

I remember discovering fiction. In about the ninth year of my life I read a popular edition of Greek mythology and it occupied my thoughts for the next two or three years, during which I explored the topic as thoroughly as I possibly could in a world where the enthusiastic reader was confined to the books they had at home or to what they could get at the local school or public libraries. I knew everything about Greek mythology, I knew all the characters and the complicated relationships between them in several versions, depending on who was telling them.

It even became a sort of obsession – later on I learned to exploit this particular state of being mentally possessed by an idea in my writing. Once I had discovered the Greeks, the time came for mythology from other cultures. I was especially fascinated by any kind of cosmogony, and by stories about the creation of the world, every narrative about how the cosmos was founded. I started to notice that some of the stories had similarities and overlapped, while others were extravagant and individual.

Apparently, an interest in mythology is part of a child’s psychological development, acting as a sort of warp thread, a scaffolding for the world, onto which individual knowledge and experience is then attached. It is a metaphorical representation of the forces in action, and it illustrates the dependencies and connections that exist between them. Nowadays myths still have an effect on children, but we find them in a slightly different place – in games and fantasy literature in comics and serials.

There has to be a paragraph in this sketch about the public library, an institution to which I owe a great deal. One of the positive aspects of Poland’s post-war political system was the nationwide availability of libraries. Sometimes that gets forgotten amid the scathing criticism of communism, and yet every village had its own, quite well-stocked library. At these modest institutions, usually run by elderly ladies, you could always sit down and read on the spot, and at some of them you were treated to tea or coffee. There were also mobile libraries, vehicles that regularly supplied books for people living at a distance from the town centre.

The books we had at home soon stopped being enough for me (especially as I was just as compulsive a reader as Kien in Canetti’s Auto-da-Fé – a whole bookcase at a time, from left to right), and the habit of looking for the local library wherever I happened to be remained with me until the days of the Internet, since when I carry books about with me in my phone and my laptop.

I was very fond of fairy tales and fables. What I loved best of all were anthologies of fairy tales from various cultures, which were readily published at the time, because the socialist regime believed implicitly in internationalism and the community of all nations. These meticulously published, beautifully illustrated volumes often had a truly artistic, unpretentious graphic design, to which today’s Disney-style kitsch cannot hold a candle. These folk tales fascinated me – generally not just invented for children, they described their worlds with tenderness, and at the same time with all the unpredictability of a free, unrestricted imagination. I had two favourite volumes – one was a collection of Andersen’s fairy tales with fabulous illustrations by Marcin Szancer, and the other contained legends and tales from the Western Lands. Now I am aware of the strength of the second of these books as propaganda, forcibly polonising the history of this part of the country, but at the time I wasn’t at all concerned about its political undertones, and I was thrilled by the stories, which were about a geography that was familiar to me and that I regarded as my own.

This mind-forming phase of my early childhood ended when our whole family moved to a small town in the south of Poland, where my parents had new jobs as teachers at a regular school. Here I developed an interest in science. I was drawn to astronomy, cosmology, physics, everything that went beyond the ordinary, everyday world and crossed the borders of the here and now. What was the origin of the cosmos? Does time flow in the same way everywhere? Are the stars eternal? How large is the cosmos? Is time travel possible? That was when I discovered science fiction, starting with some bright but intriguing stories by Sergei Snegov and some other Russian authors, who in those days were readily published in Poland, right up to Stanisław Lem, and later Philip K. Dick. I can say that I read sci-fi for the next ten years.

I started writing my first novel (which I never finished) at the age of twelve. It was about a family of wizards with lots of children, who kept moving from place to place and could never put down roots anywhere. Not a bad idea, is it? I think this was when I discovered what great satisfaction there is to be had from writing and making up stories. I drew maps of the places and portraits of the characters. I created a world.

From then on I regularly wrote short pieces of fiction, mini-stories, little images and insights. I had the occasional brush with poetry, but it never really attracted me. There was only one poet whose work I read obsessively, and who really did a lot to make me learn English – T.S. Eliot. For a long time I carried a bilingual volume of his poetry about with me, pasting every possible translation into it. I sent my bits of fiction to a young people’s literary magazine, where they were published under a pseudonym. I remember the extraordinary sense of power I felt at seeing my words in print.

By my final years at primary school I had realised that literature was more than just an ordinary pleasure. I could tell that reading opened entirely different worlds before me, allowing me to know and experience the lives of people whom I would never have the chance to meet or see with my own eyes. They became just as real to me as the people I met in my own environment. By reading I was changing my habits, acting out other existences and endlessly experimenting with my own identity. My mum can remember the time I read a novel about Eskimos and then insisted on having dried meat. Travelling in time and space was astonishingly easy – I just had to lie down on the rug or the sofa in the living room and then set off down the paths of the printed pages, to come upon another me in there, a different version of my own self.

Every year my younger sister and I were sent to my mother’s parents for a holiday in the countryside. Our grandparents lived in central Poland, where they had a lovely wooden house, part of which was rented out to holidaymakers, because there was a riverside bathing beach nearby and some huge pine forests. Here I discovered the stocks of the village library, where all the books were beautifully covered with grey paper, and thanks to some pre-determined distribution list, here you could borrow all the classics of American literature. For me those annual holidays were synonymous with a sweet and happy life entirely absorbed by reading, swimming and picking mushrooms, which to this day is my idea of paradise. What more could you want?

My grandparents, and especially my grandmother, let me in on the past, by telling me, their oldest grandchild, what had happened in the area in the past, when she was a little girl, and earlier than that as well, before she was born. Both my grandparents’ house and my aunt’s were full of knick-knacks, old photographs and souvenirs. There were some huge lime trees growing along a road known as the highway that had a longer memory of the local history than the people did. Every spot, every crossroads had its own story here. Soon, like a medium, I had soaked up all these stories, and I carried them inside me for ages, until I finally managed to get them out and turn them into a book – that was Primeval and Other Times. Perhaps at this point I should explain why the fact that this place was marked by memory and signs had such a profound effect on me. It’s because I was brought up in an area where the local cultural continuity had been cut off after the Second World War. Forced to leave, the Germans took their meanings, associations, mythology and stories with them. We were left with a blank space to fill in. As a child I was extremely surprised the first time I saw Polish gravestones in my grandparents’ village, because I had always thought the German language, especially inscribed in Gothic letters, was the special language of the dead, only used in graveyards the world over.

By the time I was at high school I was regularly reading literary magazines, and had become interested in psychology, other cultures and religions. At the same time I suddenly became fascinated by biology – on the scale of both evolution and the structure of cells, on a macro and a micro level. I came close to choosing biology for my university studies, and perhaps if I had my life would have turned out differently. But then who knows? Writing was always there, hiding behind every one of my various fascinations and hobbies. I would study the phenomenon of mitochondria, and then have no trouble returning to Faulkner or Cortázar. This was the time of my greatest literary discoveries and my most intensive literary endeavours. Never since have I read as much as I did in my four years at high school. But when the time came to choose my university studies, I felt that I should take a different path, rather than opt for literature.

My college days coincided with a rather gloomy period in my country’s history. I moved to Warsaw to go to university in the memorable August of 1980, when all Poland was on strike against the corrupt communist authorities, who were powerless to deal with the crisis. After more than a year of social unrest and major food shortages, the communists declared martial law, interned the opposition, closed the universities and fired at the striking miners. It was a difficult time for all of us. It was hard for a young woman from the provinces to find her mental equilibrium in a city that was being patrolled by the militia and the army non-stop, with a curfew in place and extreme shortages of everything necessary for life. By then I was working with patients as a volunteer, and I could see how badly the situation was affecting them, the weakest element in society, people who were lost and unwell, who couldn’t cope with the tough, ruthless demands of life at a time of crisis and lawlessness. I thought these people needed my help more than I needed to write. I saw it all as a vast sea of blameless misfortune, a cosmos of psychiatric hospitals entirely detached from the rest of the world. But it was also a time of great political activity. During the university strike I read the whole of Cortázar. During martial law it was Philip K. Dick’s Ubik that kept me company, and perhaps no other reading matter could have been better suited to the cruel, absurd reality in which I was living. All this had a major influence on me, and for some time I dropped the whole idea of writing.

My work with the patients changed me entirely, and for a while I moved away from thinking about literature and writing. By then I was already fascinated by Freud and by psychoanalysis in general; it was really thanks to his book, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, that I chose psychology as a topic for my studies, without entirely realising that in a communist country we wouldn’t be able to take up psychoanalysis.

Now I think that a key factor for my intellectual formation was the discovery of what in psychoanalysis is called the “as if” mode. Psychoanalytical theories offer us a particular way of interpreting the world, they create a language for describing it and build an internally cohesive vision. At the same time, we cannot expect them to provide experimental confirmation of the existence of e.g. the ego, the id and the superego. These are constructs that exist “as if” they were real. And here we are in the domain of myths, legends and fairy-tales. It is the same kingdom as the one occupied by mythological and literary characters, who are apparently not real, but who last for a much longer time than people, and their strange existence continues to exert a real influence on the living. This is where ideas and narratives, concepts and theories are located.

Today I can say that studying psychology and coming into contact with psychotherapy supplied me with the belief that we live in a world where many points of view co-exist. This sort of relativism shows the world as a complex, multi-layered story that, seen from various viewpoints, seems infinitely rich and is a challenge for our intellect and our psyche. If there is such a thing as an initiation into writing, I think that in my case it was to do with a minor, but essential insight – the reality in which we live as biological and psychological creatures can be constantly re-interpreted in new ways. In my third year at university I chose to specialise in clinical psychology.

After college I felt I had nothing left to do in Warsaw, a city I had never liked, and that I found artificial and unfriendly. So once I had decided to work in psychiatry, I returned to the remote provinces of Lower Silesia. I settled in Wałbrzych, a lovely town that had been ruined by industry, and that before the war was called Waldenburg. Here I got married to another psychologist and had a son. At the same time, I was honing my professional skills, and after a while I timidly went back to writing. In this period I plumbed the depths of psychology, including Jung, who kept me company for a long time, Eliade, Neumann and Hillman. Now I think I devoted myself to my work far too intensely; quite early on I reached professional burn-out, and perhaps a sense of the hopelessness of what I was doing. I took an extended break and went away for several months to London, which turned out to be a great inspiration and a source of new energy. I came home from London with several literary texts, a head full of new ideas and a suitcase full of books – mainly about feminism (there I had discovered the wonderful feminist bookshop, Silver Moon) and various oddities that greatly interested me at the time. A year after my return I had written my first novel and two or three short stories.

It took a long time to find a publisher for my first novel, The Journey of the People of the Book. It was a time of total market transformation in Poland – the socialist economy was being entirely replaced by the new, capitalist free-market economy, so there was chaos; the large state publishing houses were collapsing, while others that until recently had been illegal were emerging from the underground. The opening up of the book market gave rise to a tidal wave of translations from English – everything that couldn’t have been published until then suddenly appeared on sale, including crime fiction, thrillers and horror stories. All these were on display in the bookshops, in glaringly colourful covers. A writer (and especially a female one) with a Polish name had virtually no chance of breaking through this tsunami. There was probably no harder time to publish one’s first novel, and worse yet, a fantastical, philosophical tale about the limits of human perception. But it was at a small, until recently underground publishing house that I found support for my book, which in those days might have seemed a complete oddity.

Working on this simple little book taught me a lot – not just how to tell stories, and how to create characters and dialogue, but also how to edit the text and how to do the research. The book finally came out almost three years later, in 1993, and won a prize for the best debut, awarded by the Polish Book Publishers Association. That was probably why I didn’t have to look hard for the next publisher – my second book was accepted by the prestigious state publishing house, PWN (which no longer exists). After the success of my third novel, Primeval and Other Times, which was shortlisted for Poland’s most important literary prize, the Nike, I realised that from now on writing was going to be all I did, although for ages I went on regarding it as a bit of a shameful hobby, and it was a long time before I could admit to myself that it had actually become my profession. I remember the day at an airport when I had to fill in an immigration form, and I stood there for ages with my pen hovering over the box marked “Profession”, not knowing how to fill it in. Finally I plucked up the courage to put: “Writer”.

A fact I consider important to my biography is that I bought an old house in Kłodzko Valley, where I gradually made myself at home. Going deep into nature, but also into the cultural realm of Kłodzko Valley inspired me to look at my writing, and at life in general, in a different way. Here my interest in ecology intensified. The books that resulted marked the start of my first literary self-reflection, giving thought to a style of my own, to the pitfalls of linear story-telling, to ways of creating characters, and to a panoptic perspective. House of Day, House of Night, which then came into being, has had an evident influence on all my later work. My short stories were written in the same spirit. These books were about people’s attempts to put down roots in particular places, traditions or culture as a sustained effort that’s more or less doomed to failure, and they showed how hard or even impossible it is, because of the contradictory forces that do battle inside us – a sense of striving for security and stability, struggling against an uncontrollable, nomadic curiosity about the world.

The turn of the centuries was a period of intensive travel, during which the idea of a novel about travelling occurred to me, a constellation work to describe the atavistic nomadic nature that lies deeply hidden inside us. I owe a lot to those journeys, and regard them as a special sort of university. The most intense and important trips were the ones I took alone, when I had to deal with culture shock, ignorance of the language, and homesickness. The result of them was Flights – a very important book for me, in which I applied all my literary intuition, and which I called a “constellation novel”. It was an important time for me for personal reasons too. My relationship came to an end, and I moved house, but it never occurred to me to give up writing. In any case, I didn’t really know how to do anything else. Nor did it occur to me to emigrate, though I had often lived abroad for a longer or shorter time.

It’s hard to say how many years it took me to prepare to write The Books of Jacob. The history of Jacob Frank wasn’t very well known, so I had to do a vast amount of research, which stretched over several years, like regular academic studies. It also included two international journeys, during which I went from place to place in the footsteps of the historical characters who feature in the book. And it also meant hours on end slogging over documents, leafing through history books and patiently collecting details and local colour.

The rest is boring. I sit and write. When I’m not writing, I’m gathering material, exploring topics, coincidences and peculiarities. I still read a great deal, whatever happens to come my way. And I learn a lot from the cinema – these days I think it’s the cinema that wears the story-telling crown, and we writers can observe plenty of good dénouements there.

For the past fifteen years or so I’ve been living in Wrocław and in Kłodzko Valley. I don’t travel as often as in the past. As time goes by I’m becoming more settled and more introverted. I don’t need so much stimulation from the outside any more. I have a small family: my husband, my son, my sister and my mum. There’s also my old dog, Nina, who has been with us for well over ten years through various moves, and who has patiently adapted to each new home.

I’ve always been aware that as a writer I belong, like it or not, to the great land that is Central Europe (though there are many people who doubt whether such a thing really exists). All I know is that it’s the space between the West and the East, the North and the South. Time flows differently here, not in a linear way, but by turning circles, although nobody ever learns the lessons of history. Everything here seems fluid and sketchy – the borders wander, and so do the nations, the language influences shift, and views and ideas mix as in a melting pot. It’s a place where things bud and come into being, but afterwards the seeds always go off into the world and gather strength somewhere else. It’s a crater which pours out lava in the form of wave after wave of migrants who power Western Europe, and above all the New World. I’ve always felt myself to be part of this land, and as proof I’m happy to offer the fact that in the course of her life my grandmother, who had the same name as me, had four different passports.

I hope that one day I’ll manage to write about the mixed population that lives here, including its migrations and its eternal sense of instability. I am consciously trying to refer to this indescribable culture in what and how I write. This is not the place to go into digressions on the topic of this “Centreworld”, so all I shall say is that here we have leanings towards the grotesque and towards gentle surrealism, we’re drawn towards the uncanny and we believe in the power of the word, the power of language. A huge proportion of the population writes poetry. Here any form of realism seems suspect, and any kind of permanence seems temporary. It’s a good place to write. And a good language – Polish can be difficult to learn, but thanks to its anarchic nature and a sort of wonderful lack of precision it offers a huge sense of freedom.

I have ideas for several more books, and am now working on two of them. Writing continues to give me great pleasure.

Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Figure 2.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.