Interview with Andrea Ghez, March 2021

“I see being a scientist as being a puzzle solver”

Nobelprize.org interviewed Andrea Ghez on International Women’s Day, 8 March 2021. She told us how her interest in science and the universe was sparked, what advice she would give to young researchers and why she loves being a scientist.

Could you tell me a little bit about your childhood? Were you interested in science as a young child?

Andrea Ghez: Hindsight is always 20/20 in terms of where our interest in what we do originates. But I think I can identify that point in the moon landing. I was four, but I think that was what got me thinking about space and the enormity of space. But I think it’s also important to point out that at the same time I was saying I wanted to be an astronaut I was also saying I wanted to be a ballerina. So it wasn’t as if I, as a child, really understood science is my passion.

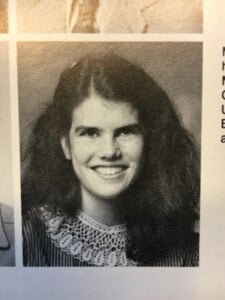

Andrea Ghez’s senior year University of Chicago Lab School (high school) yearbook photo, 1983.

Photo: University of Chicago Laboratory Schools

I’d say what definitely emerged was that I love puzzles – jigsaw puzzles, crossword puzzles, Sudoku. I see being a scientist as really fundamentally being a puzzle solver. Putting together the pieces, trying to find the evidence, trying to see the bigger picture.

I understood that I was interested in math and science by the time I went to college, I wanted to go to MIT. So I was clearly driven in that direction, but I went to college as a math major. But I was definitely thinking a lot about space. It used to keep me up at night. The enormity of space, just how small we are, our space and time is so insignificant on the scale of the universe. It’s both fascinating and horrifying at the same time. And I think that both of those aspects really took hold of me when I was young.

Was there a particular person, like a teacher, a mentor, a role model that influenced you?

I was so lucky. I had a lot of really wonderful role models in my life for lots of different aspects of it. First my parents were just great role models. My dad was a professor, so I was really exposed to the world of academia. What being a professor looked like, felt like, and he was always encouraging my curiosity. And then my mother was the director of a contemporary art gallery. So I had a really strong role model in terms of women going out and leading. I had an uncle who was a physicist. I have very clear memories of sitting around the kitchen table with my uncle and my dad talking about how the early Greeks learned, figured things out. And there was something so compelling about that – that process of the early understanding and the beauty of their discovery or their logic. So I think my uncle was a big figure early on.

And then there were teachers, I had an early chemistry teacher who was really encouraging. I was really fortunate in a sense that later in life I didn’t have many women science teachers. So she was an early encourager or advocate. I often tell my students that the most important decisions you make, especially later in life in grad school and even in college, is who your mentors are, who you work with because they just have such an important role in your professional development. You really want to work with people who have your back, who really want to encourage and nurture your development as a scientist. I was lucky as an undergrad to work with Hale Bradt and then as a grad student to work with Gerry Neugebauer, as well as Anneila Sargent who was sort of a secondary advisor to me. These were people who were just wonderfully supportive. So I’m really grateful.

Are there any particular lessons or life skills that you learned from them?

Oh, gosh, I’ve learned so many things from them. Everybody has something to teach you. I think that’s one of the things that I’ve taken away along the way. That being able to interact with a large variety of people is important because each of those interactions has the potential to teach you about something. So my mother: ‘Just do it!’ was her, she had that down before Nancy Reagan did.

I think there were some really important lessons along the way about understanding how to deal with challenges, how to translate challenges into opportunities and Anneila Sargent, was particularly good – she provided me critical advice at a moment in graduate school where there was a hiccup and how to move a hiccup over into an opportunity, and figuring out how to stay focused on where you’re trying to go.

Similarly, and probably the most important lesson I think I ever learned from Gerry Neugebauer, as my PhD advisor, was pay attention to the data. That’s where the information is. And that the story may evolve around the data because more information will keep coming in, but you really have to pay attention to the data.

Andrea Ghez during the interview with nobelprize.org.

You talked about translating hiccups into an opportunity. How do you deal with challenges?

It’s really important to realise that hiccups are a natural part of doing research. And that’s why I think that ability to deal with hiccups is so important. Research and discovery is about exploring our frontier of knowledge, where we don’t know, we don’t have everything worked out. It’s not neat and tidy.

I think it’s just an acceptance that things are hard and messy, things are complex. Your job as a scientist is to figure them out. You have to relish in the mess. It’s almost like the process of putting things together. Or if we come back to the puzzle analogy – you’re trying to figure out which goes with which, so some of them aren’t going to work and if you can view that as progress.

I think it’s just a viewpoint. I’ve now come to understand that’s something I take for granted, it isn’t necessarily how the world views things. I think it’s really interesting when things don’t work because that’s the path to discovery. Scientifically when you discover things that are inconsistent with how our current paradigm tells us things should look, it’s like, ‘Oh, well, this is interesting! There’s something more to be discovered here.’ In a sense, you could say that’s a failure of the theory, but it’s actually a huge opportunity for discovery and understanding. So if you really embrace that, if things don’t work, there’s something that can be learned.

Is there a particular piece of advice that you would give to a young scientist?

These days, one of the things I like to talk about with young scientists in my group, or anywhere is the idea that you want to take stock every few years of three things:

One is what is it that you love to do, what gives you pleasure? What do you find intriguing?

Two is what is it that you want to explore? It’s important to keep exploring because you don’t know what you’re going to enjoy until you try it. I’ll come back to an example of that for me, which really taught me that lesson.

And then the last thing is, how do you give back, how do you open up that opportunity for others to figure out what they enjoy? You’ve benefited from mentors. So how can you give back?

So those three things I think are useful to continually take stock of, because as you evolve the answer to the first thing isn’t going to stay the same. It’s just going to keep changing. So check in with yourself every once in a while.

The example that I like to share about trying things that you don’t know, or you might be afraid of, for me was public speaking. Given that I do so much of it now, I was terrified of public speaking, so much so that where I chose to go to graduate school was based on whether or not I had to teach, When I got to graduate school, I gave my first research talk and I shook from my head to my toe. I was so nervous. And my PhD advisor, Gerry Neugebauer said, you have to teach, you’ve got to get over this. So I ended up teaching and I discovered that I really enjoyed it. I quickly decided that I really wanted to teach the intro physics classes because there were very few women. So I took something that I liked, which is trying to expand or encourage young girls along for the ride. And it was just a great experience. I think I discovered my interest and passion for teaching as well as research.

Physics laureate Andrea Ghez holding her Nobel Prize diploma.

© Nobel Prize Outreach. Photo: Annette Buhl

Is there any advice that you would give to young female scientists? What do you think we should do to encourage more women to do science and increase diversity in general?

Well there’s two parts of that question, I think, which is how do you succeed? I think there’s some general advice, no matter who you are, which is the importance of community, having people that you can turn to to support you through all the bumps and wiggles that whatever path you’re on presents. That’s your support system. It’s your network, your professional family that no matter who you are you really need. I think the challenge when you’re a minority, no matter what your minority is, is making sure that that’s in place. There’s just less people to choose from that look like you, although, it’s true, that you can get support from people who don’t look like you. It’s just that you need a support system.

The other part of your question, is encouraging diversity. I think we learn so much when we bring different points of view to the table, I think that’s a really important part of the conversation. I personally think that the people with the biggest passions for doing the work are going to do the best work. So I think in some sense, the challenge, or the opportunity is, to feed that desire – that desire to succeed or the quest to want to know. To not suppress it, or inhibit those who have that desire to understand. As kids we’re all so curious, that’s just the way we learn about the world. I think for us really the challenge is to encourage that no matter who you are or what you look like.

You’re obviously very passionate about science and physics, but what do you like to do outside of work?

I think it’s really important to have other things for many reasons – one it’s just healthy and two, sometimes you just need to look away from your problem, in order to sort it out, in some sense to give your brain a break or relax and see something from a different perspective.

I’ve always enjoyed doing something athletic. So today I love swimming but even that has been an interesting evolution. I started in high school as a runner and as a field hockey player. I went to college and I joined the cross country team, so I got into marathon running. Then I decided at the end I wanted to do a triathlon, but my swimming was really weak. So I joined the MIT swim team in my senior year for a bit. As a graduate student, I got into masters swimming and I’ve done masters swimming ever since.

For me, swimming or just being active has two really important components. One is that physically it’s really important to stay healthy. Often times I have to say the problems I have at work get sorted out in my head in the pool – it used to be running now it’s swimming. And then in terms of this idea of having a network of people, I love the masters swim team, it brings together people from all communities. So I have the social network, or place, also where I’m not a minority. At work there aren’t that many women, but it’s really nice to be part of a community where you don’t stand out. It also just gives you sort of fortitude, that’s really important.

I should say my other thing I do a lot of outside of work is I have two kids, so I take care of them. I mean they’re much older now, but being a mom has been a great addition to life. I’m really glad I got that opportunity. I think I’ve learned a lot from being a mom.

What do you like best about being a scientist?

Gosh so many things. Maybe the best thing is I have a job I love. That’s the ultimate privilege in life, to love what you do. I feel very fortunate.

That’s not quite what you asked though. About being a scientist: I think it is being able to pursue questions that you define for yourself. Sometimes there’s a lot of freedom – no one’s telling you what to do. You’ve got to figure it out yourself, but that’s an amazing opportunity in life.

Andrea Ghez next to the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRC) before it was decommissioned and brought down to the summit.

Credit: Rick Peterson/W. M. Keck Observatory

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

First published: March 2021

Nobel Prizes and laureates

See them all presented here.