Popular information

Information for the public:

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2010 (pdf)

Populärvetenskaplig information:

Nobelpriset i fysiologi eller medicin år 2010 (pdf)

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2010

is awarded to

Robert G. Edwards

“for the development of in vitro fertilization”

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2010

Robert Edwards is awarded the 2010 Nobel Prize for the development of human in vitro fertilization (IVF) therapy. His achievements have made it possible to treat infertility, a medical condition afflicting a large proportion of humanity including more than ten percent of all couples worldwide.

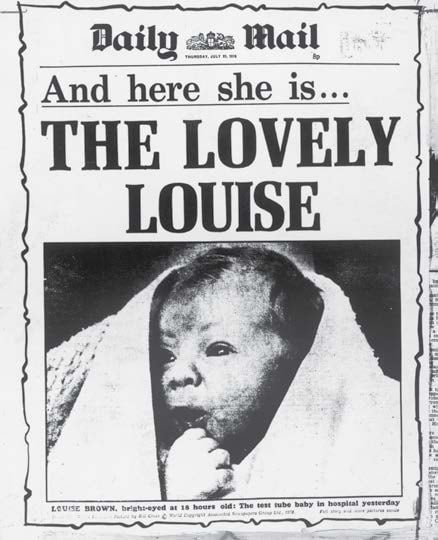

A newborn baby appeared on the front pages of newspapers all over the world 27 July 1978. A baby girl in perfect health who was going to be named Louise: what was so sensational about that? It was the way she had been conceived. For the first time ever, a child had been born after “test tube fertilization” of a woman who had been diagnosed as infertile.

Until then the possibilities of treating infertility had been limited. The understanding of the fertilization process was incomplete and those who suffered an inability to conceive a child usually faced life-long disappointment.

Infertility – a medical and psychological problem

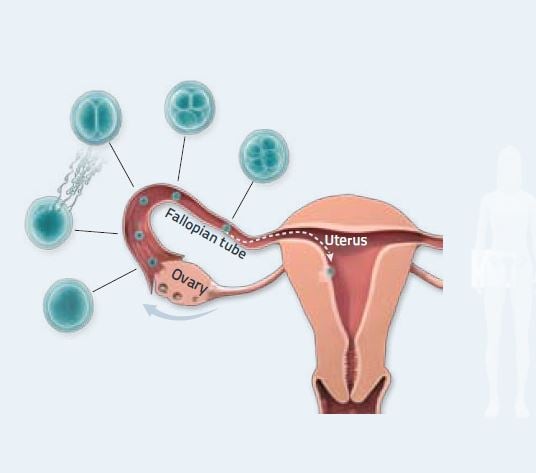

where fertilization can take place. Infertility can be caused by

several different factors, including poor sperm cell quality, lack

of egg cells, or damage to the fallopian tube. Illustration: Mattias Karlén. © 2010 The Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine, Karolinska Institutet

A question of timing

At the beginning of the 1950s Robert Edwards was working on his doctoral thesis at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. His topic was reproduction in mice. He spent many hours in the laboratory – frequently at night, because that was when the mice usually ovulated. It was there he got his idea for future treatment of infertility: maybe the problem could be solved by lifting human fertilization from inside the body out into a Petri dish? In that way the fertilization process could be helped along and the obstacles that most frequently cause infertility could be circumvented.

After moving to London at the end of the 1950s and starting to do research on human reproduction, Robert Edwards found an opportunity to test his ideas. With the help of a gynaecologist he gained access to small pieces of ovarian tissue from which he could isolate a few undeveloped egg cells, oocytes. If the oocytes were to be fertilized, he first needed to get them to mature – a process that occurs naturally inside a woman’s body every month but that would turn out to be difficult to replicate in the laboratory.

Other researchers had succeeded in getting oocytes from rabbits to mature and had also managed to fertilize them. But these methods did not work on human oocytes, which clearly followed a different life cycle. Robert Edwards tried everything, repeatedly adjusting hormone levels, culture media and time schedules, but the precious oocytes refused to emerge from their quiescent state and become receptive to fertilization. The work was also impeded by a constant lack of oocytes. After several years’ work and a move to Cambridge, Edwards finally found the decisive piece of the puzzle. One problem had been that human oocyte development followed an unknown schedule that differed from those of all the other animal species he had studied. It dawned on Edwards that human egg cells required an entire day and night to mature – twice as long as rabbit oocytes. He had now discovered the window of opportunity during which fertilization was possible.

The first test tube fertilization

With this discovery, the way to IVF lay open. Robert Edwards, in collaboration with various colleagues, had learned to control the oocyte’s maturation so that it would be ready for fertilization outside the body. He had also defined under which conditions spermatozoa become activated and can fertilize the egg. On 15 February 1969 the results were presented in an article in the journal Nature, authored by Robert Edwards and his co-workers. The summary on the first page of the article stated modestly: “Human oocytes have been matured and fertilized by spermatozoa in vitro. There may be certain clinical and scientific use for human eggs fertilized by this procedure.”

The reactions, however, were anything but modest. At the time, this research and the plans for IVF treatment aroused fascination but also public debate, and the Physiology laboratory at the University of Cambridge was invaded by journalists who wanted to interview Robert Edwards.

Fruitful collaboration

Though advances had been made, a problem remained: fertilized eggs stopped developing after a single cell division, and this probably had something to do with the oocytes having matured in the laboratory. Robert Edwards realized that the only way forward would be to use eggs that had been allowed to mature in the ovary before being taken out. To get hold of such cells he initiated collaboration with gynaecologist Patrick Steptoe at the district hospital in Oldham. Steptoe was a pioneer in the new field of laparoscopic surgery, which appeared ideal for Edwards’ purpose.

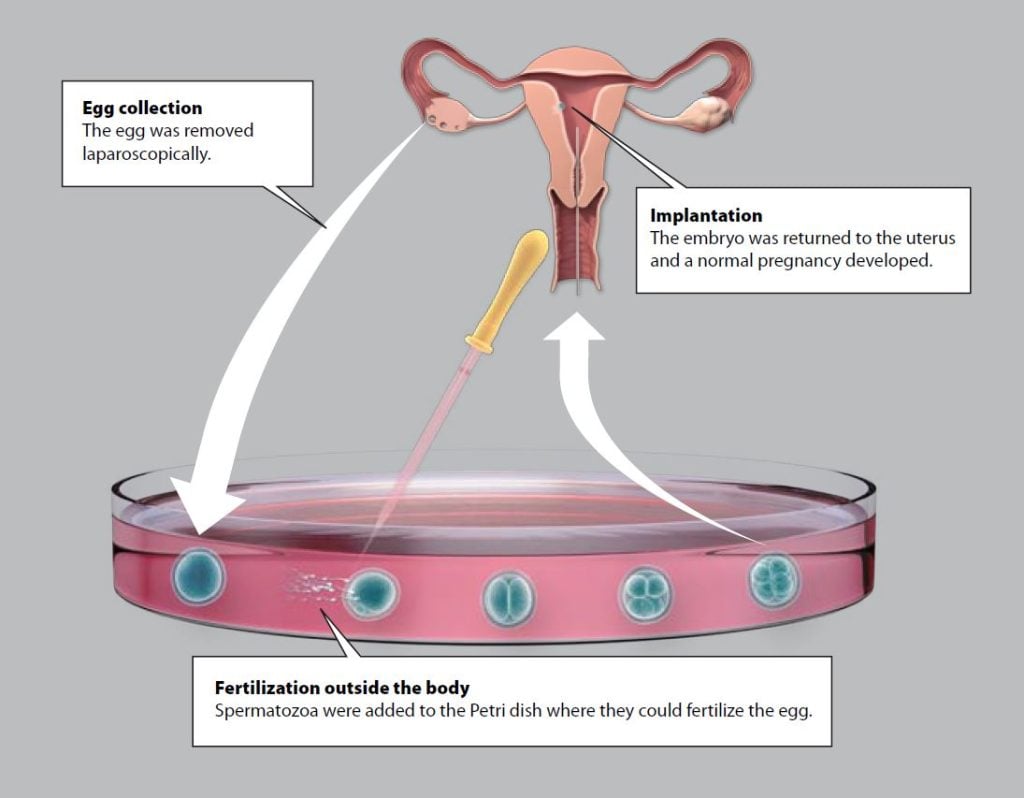

Patrick Steptoe was the clinician who worked with Robert Edwards to develop IVF from experimental technique to medical therapy. Women were first treated with hormones to stimulate maturation of several eggs in their ovaries. Then, using laparoscopic techniques, Patrick Steptoe extracted several eggs from the ovaries; Robert Edwards put these oocytes in culture dishes and mixed them with spermatozoa. The fertilized eggs now divided several times and developed into early embryos consisting of eight cells.

Research against the wind

Everything looked promising but the research grew increasingly controversial. Several bishops and ethicists demanded that the project be stopped, whereas others supported it. Critics considered the research ethically questionable; one of their concerns was that children conceived through IVF might have birth defects. Large parts of the scientific establishment also disapproved of the research. The British Medical Research Council questioned both the safety and the long-term usefulness of infertility treatment and turned down an application for research funding.

Robert Edwards viewed these ethical questions with profound earnestness. Early on, he wrote articles about the issue and advocated implementation of strict ethical guidelines for research on human stem cells and embryos. However, he considered the risks of IVF to be small and was determined to bring his work to fruition. A private donation enabled the project to continue after other funding had been withdrawn.

The birth of Louise Brown

Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe were now working hard to get past the last obstacle: transferring the fertilized egg back into the woman so a pregnancy could be established. At this time Robert Edwards travelled constantly back and forth between Cambridge and Patrick Steptoe’s workplace at the hospital in Oldham, nearly 300 km away. After more than a hundred failed attempts to establish a pregnancy, they decided to skip the hormone treatment aimed to stimulate the woman’s ovaries to produce several mature oocytes. Instead, they would rely on the single oocyte that matures in the course of a natural menstrual cycle. By analysing the patient’s hormone levels they were able to pinpoint the optimal time for fertilization and increase the likelihood that a child would be conceived.

In November 1977, Lesley and John Brown came to the clinic after nine years of unsuccessful attempts to have a child. An oocyte was fertilized in the test tube and when it had developed into an embryo with eight cells, it was reimplanted in the mother-to-be. The resulting pregnancy went to term and the world’s first test tube baby, Louise Brown, was born by caesarean section 25 July 1978.

The world’s first IVF centre

To everyone’s relief, Louise Brown was in perfect health. On 4 July 1979 the feat was repeated with the birth of the world’s second IVF baby, a boy. But the research granting agencies were still sceptical and reluctant to help Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe open a clinic where the technique could be refined. Once again, they moved forward with private financing.

In an idyllic manor house in the village of Bourn on the outskirts of Cambridge they now opened Bourn Hall Clinic – the world’s first IVF centre. At Bourn Hall, Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe were to develop their techniques, simultaneously training gynaecologists and cell biologists from all over the world. The world’s first ethical committee for issues related to assisted conception was also established to serve as a sounding board for these activities. In the 1980s the IVF technique gained wider acceptance and the number of IVF babies grew ever larger. In 1986, one thousand children had been born after IVF at Bourn Hall: about half of all the IVF babies in the world. Patrick Steptoe remained Medical Director of Bourn Hall Clinic until his death in 1988, and Robert Edwards was its Research Director until he retired.

IVF is improved and spreads around the world

The IVF technique is now established worldwide and has undergone several important improvements. For one thing, individual spermatozoa can now be injected directly into an oocyte in the culture dish, which gives men with defective sperm production a better chance of having children. Ultrasound is used to identify egg follicles that may contain mature eggs, and eggs are now removed from the follicles through a fine needle rather than laparoscopically.

Oocytes and embryos produced with IVF can now be frozen and saved for later use. Scientists are currently developing techniques that enable use of immature or mature frozen oocytes for IVF, a method that would help ensure that women at risk of ovary damage (e.g. because of cancer therapy) will be able to have children later in life.

IVF is a safe and effective treatment. Between 20 and 30 percent of the fertilized eggs eventually develop into live-born children and the majority of all infertile women treated with IVF succeed in having a child. The risk of complications, such as premature birth, is small provided only one egg is implanted. Long-term follow-up of IVF children has shown them to be just as healthy as other children. So far, around four million children have been born thanks to IVF. Louise Brown and other IVF children have given birth to healthy children of their own, and this is perhaps the best proof of the success and safety of the IVF technique.

Millions have benefitted

It is not always immediately obvious how society will benefit from scientific discoveries. But Robert Edwards’ research attracted public attention right from the start and its positive impact on people’s lives is now almost unparalleled. Millions of people would not even exist were it not for Robert Edwards’ contributions, and even more owe him thanks for a long-awaited child or a cherished sibling.

The Laureate

ROBERT G. EDWARDS

Robert G. Edwards was born in 1925 in Batley, Yorkshire, UK. For most of his academic career in reproductive physiology, he worked in Cambridge, England, where he and his co-workers also established the world’s first IVF centre, Bourn Hall Clinic. Robert Edwards is now Emeritus Professor at the University of Cambridge.

The editorial committee for this year’s popular presentation of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine included the following scientific advisors, all professors at Karolinska Institutet: Göran K Hansson, Medicine, Secretary of the Nobel Assembly; Outi Hovatta, Obstetrics and Gynaecology; Christer Höög, Genetics; Klas Kärre, Immunology, Chairman of the Nobel Committee; Hugo Lagercrantz, Paediatrics; Urban Lendahl, Genetics.

Text: Ola Danielsson, medical journalist

Translation: Janet Holmén, editor

Illustrations and layout: Mattias Karlén

© The Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine, Karolinska Institutet

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.